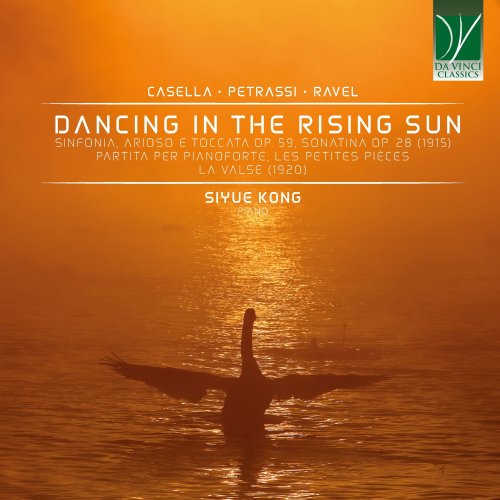

Siyue Kong - Casella, Petrassi, Ravel: Dancing in the Rising Sun (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Siyue Kong

- Title: Casella, Petrassi, Ravel: Dancing in the Rising Sun

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:04:30

- Total Size: 223 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Sinfonia, Arioso e Toccata, Op. 59: I. Sinfonia

02. Sinfonia, Arioso e Toccata, Op. 59: II. Arioso

03. Sinfonia, Arioso e Toccata, Op. 59: III. Toccata

04. Sonatina, Op. 28: I. Allegro con spirito

05. Sonatina, Op. 28: II. Minuetto

06. Sonatina, Op. 28: III. Finale: Veloce molto

07. Partita per pianoforte: No. 1, Preludio

08. Partita per pianoforte: No. 2, Aria

09. Partita per pianoforte: No. 3, Gavotta

10. Partita per pianoforte: No. 4, Giga

11. Les petites pièces: No. 1, Petite pièce

12. Les petites pièces: No. 2, Oh les beaux jours! I Bagatelle

13. Les petites pièces: No. 3, Oh les beaux jours! II Le petit chat Miró

14. La Valse, M. 72

This Da Vinci Classics album features works by three twentieth-century composers, i.e. Alfredo Casella, Goffredo Petrassi, and Maurice Ravel. Of the three, doubtlessly Ravel is the best known internationally; yet, the true gravitational centre of this album is represented by Alfredo Casella, to whom the other two seem to direct their gaze in their lives and compositional output.

Casella was born in Turin, Italy, in 1883. In his childhood he did not receive any regular schooling, either as concerns general education or as a musician. Yet, he grew up in a highly cultivated and musical environment. Some of the most important figures of contemporaneous Italy were regular guests at his parents’ home, and he was homeschooled by his mother, a well-educated woman, and by his father, a famous cellist.

Already at the age of 10, Casella made up his mind: music was to be his life, in spite of his many other interests. He debuted as a pianist in Turin, and, encouraged by some leading musicians of the era, he left Italy for Paris in order to attend the conservatoire of the French capital. This was done at the price of great sacrifice, since Casella lost his father prematurely. In Paris, however, Casella received the best possible tuition in the fields of piano, composition, and several others. At 19 he had finished his studies, and was already perfectly introduced in the haute société of the ville lumière, befriending some of the most important figures of the time: from Zola to Gide, from Proust to Daudet or Degas, but also, of course, musicians such as Enescu, Ravel, and Debussy – first and foremost among them was Gabriel Fauré, who gave him the most important stimuli for his musical life.

Casella was also active as a pioneer of the revival of harpsichord playing, within the framework of the prehistory of the early music movement. He began to conduct regularly, and was particularly known as an appreciator of Mahler’s works.

Casella’s return to Italy was paradoxically favoured by the international tensions which ultimately led to World War I. He established his Italian home in Rome, where he quickly became one of the protagonists of the local musical life. He founded countless initiatives – some of them short-lived, but nonetheless highly significant – for the promotion of new music and its performance in Italy. Still, he was at least equally interested in the music of the past, which represented history and identity.

He toured extensively the US, where he was highly appreciated and about which he was a perceptive observer, reporting on the musical life of the States on European journals.

He continued to perform as a pianist, both as a soloist and as a member of the legendary Trio Italiano, to write (both music and essays), to be active as a member or Board member in many associations, and to teach extensively, both piano and composition.

In the summer of 1942, Casella’s health suddenly failed him, and for the remaining years of his life he was in constant pain, although he tried to maintain some concert engagements. In spite of his illness, however, his home was constantly the harbour of those who looked to him as to a reference point for Italy’s musical and cultural life. One of Casella’s last masterpieces is his Missa Solemnis Pro Pace (1944), where he gives voice to his religious feelings in dialogue with the tragedy of World War II.

Two among the most important piano works by Casella are recorded here. The first is his Sonatina op. 28, which has been defined as the icon, within Casella’s piano output, of his point of highest closeness to the world of Schoenberg (whose Pierrot Lunaire was premiered in Italy thanks to Casella’s tireless efforts). However, in this work from 1916 (i.e. shortly after Casella’s return to Italy), there are also many echoes from Stravinsky, Bartok, Ravel, and even Scriabin.

The deep care with which Casella shaped this work is evident in the lengthy instructions to the performer he provides in the first edition: «the execution of this little work can only be done with perfect consciousness of all the secrets of the modern pedal, and consequently knowing how wonderful and peculiar a poetry can be expected through a complex, very high ‘pedalistic’ registration. For these indications are superfluous; the performer will understand me without doubt. However, here and there, I thought it useful to guide the performer, compromise certain sounds that I hold dear».

It is in fact Casella’s most progressive work, where reminiscences from the style and works of the great modern composers are ceaselessly found, albeit in dialogue with the composer’s own personality.

Both this Sonatina and the Sinfonia, Arioso e Toccata are reminiscent of the Sonata form, and are the only Sonatas completed by the composer. The style of this work unavoidably suggests parallels with the political situation in the surrounding European countries. In spite of the diminutive title, it is one of Casella’s most demanding piano works, as concerns performing technique, aesthetical perspective, and interpretive traits. This work also mirrors the difficult moment Casella was living – as a citizen of a country at war, as a recently returned “outsider”, as a person of culture and conscience.

This Sonatina underwent a rather complex compositional process, during which it lost a Preludio allegretto, which would later be published as the second of the Deux contrastes op. 31.

Similar to the Sonatina op. 28, also the Sinfonia, Arioso e Toccata is a “collage of themes”, although in the earlier work the various themes seem to have been collated more tightly. In spite of this, memories and suggestions from the first movement are found and recur throughout the work. Still, it is a challenge for the interpreter to sustain the work’s narrative during its whole length.

The most obvious inspiration for this work came to Casella from Beethoven’s last Piano Sonata, op. 111. This inspiration regards both direct allusions, and the work’s structure. Casella’s admiration for Beethoven was transparent and took a variety of forms, including extensive instructive editing. The work’s title, furthermore, unavoidably brings to mind the great piano “triptychs” by César Franck. Possibly, these fascinating allusions to the “first of the Romantics” (as Casella considered Beethoven) and to one of the last representatives of Romanticism were intended to dispel the aura of anti-Romanticism which was preventing Casella’s full acceptance within the Italian musical scene.

The encounter with Casella was fundamental for the musical and human development of Goffredo Petrassi. Petrassi would recall that he had known Casella long before Casella could get to know him; and Casella’s influence on Petrassi is particularly evident precisely in the Partita. Furthermore, Casella’s interest in the music of both the past and the future was crucial for the young Petrassi.

Similar to Casella, also Petrassi lacked regular schooling, but their respective backgrounds were very different. Instead of Casella’s high-class and high-cultivated milieu, Petrassi came from a very modest household, and his formal education was very limited. However, being highly curious and interested in the spirituality of culture, Petrassi studied throughout his life, becoming a person of really noteworthy preparation. Petrassi had received his first musical education as a choirboy; that experience brought him a little income – which was very welcome given the situation of his family – but, most importantly, first-hand knowledge of the great Renaissance polyphonic repertoire.

As the young Petrassi was working at a music shop, a professor of piano of the Conservatory of Rome noticed him and invited him to study at the prestigious institution. Already before beginning his formal education, however, Petrassi had composed some important works, including the Partita recorded here. Indeed, Petrassi’s compositional output does not include many piano works, but this is compensated by their high musical and technical quality. This homage to the world of Baroque music, in four movements, is firmly rooted within the Classical tradition. The three pieces of Oh, les beaux jours were composed during wartime (1941-3) and later elaborated in a modified form in 1976. In their definitive shape they were composed for, and dedicated to, pianist Lya De Barberiis, one of Casella’s favourite students and a longtime champion of new music. Petrassi sent her the manuscript inviting her comments, since he did not feel particularly confident when writing for the piano. When she retouched a few details, and then played the work for him, he said: “Lya, you don’t play what I wrote, but what I thought!”.

The last piece in this recording is the exceedingly famous La Valse by Maurice Ravel. Here the connection with Casella is once more very clear, because Ravel and Casella premiered together the piano duet version of La Valse. The piece had originated as an idea through which Ravel had initially intended to pay homage to Vienna (in fact it was to be titled either Wien or Vienne). Later, legendary choreographer Diaghilev asked him to write a ballet score evoking the luxury and fascination of fin-de-siècle Vienna. However, the result did not correspond to Diaghilev’s expectations. Not without reason, he defined Ravel’s composition as a “portrait of a ballet” rather than a ballet proper. But this outraged Ravel, and ended their friendship. In spite of this, La Valse has been set to dance many times, and, in its concert form, has acquired extraordinary fame in the versions for solo piano, for piano duet, and for orchestra.

Therefore, the complete album allows us an experience of the fecund and creative atmosphere of those years, and to deduce the crucial role played by Casella as a protagonist of the intellectual and cultural life of his time. And, of course, to savour wonderful musical pieces which are, frequently, less known than they would deserve.

01. Sinfonia, Arioso e Toccata, Op. 59: I. Sinfonia

02. Sinfonia, Arioso e Toccata, Op. 59: II. Arioso

03. Sinfonia, Arioso e Toccata, Op. 59: III. Toccata

04. Sonatina, Op. 28: I. Allegro con spirito

05. Sonatina, Op. 28: II. Minuetto

06. Sonatina, Op. 28: III. Finale: Veloce molto

07. Partita per pianoforte: No. 1, Preludio

08. Partita per pianoforte: No. 2, Aria

09. Partita per pianoforte: No. 3, Gavotta

10. Partita per pianoforte: No. 4, Giga

11. Les petites pièces: No. 1, Petite pièce

12. Les petites pièces: No. 2, Oh les beaux jours! I Bagatelle

13. Les petites pièces: No. 3, Oh les beaux jours! II Le petit chat Miró

14. La Valse, M. 72

This Da Vinci Classics album features works by three twentieth-century composers, i.e. Alfredo Casella, Goffredo Petrassi, and Maurice Ravel. Of the three, doubtlessly Ravel is the best known internationally; yet, the true gravitational centre of this album is represented by Alfredo Casella, to whom the other two seem to direct their gaze in their lives and compositional output.

Casella was born in Turin, Italy, in 1883. In his childhood he did not receive any regular schooling, either as concerns general education or as a musician. Yet, he grew up in a highly cultivated and musical environment. Some of the most important figures of contemporaneous Italy were regular guests at his parents’ home, and he was homeschooled by his mother, a well-educated woman, and by his father, a famous cellist.

Already at the age of 10, Casella made up his mind: music was to be his life, in spite of his many other interests. He debuted as a pianist in Turin, and, encouraged by some leading musicians of the era, he left Italy for Paris in order to attend the conservatoire of the French capital. This was done at the price of great sacrifice, since Casella lost his father prematurely. In Paris, however, Casella received the best possible tuition in the fields of piano, composition, and several others. At 19 he had finished his studies, and was already perfectly introduced in the haute société of the ville lumière, befriending some of the most important figures of the time: from Zola to Gide, from Proust to Daudet or Degas, but also, of course, musicians such as Enescu, Ravel, and Debussy – first and foremost among them was Gabriel Fauré, who gave him the most important stimuli for his musical life.

Casella was also active as a pioneer of the revival of harpsichord playing, within the framework of the prehistory of the early music movement. He began to conduct regularly, and was particularly known as an appreciator of Mahler’s works.

Casella’s return to Italy was paradoxically favoured by the international tensions which ultimately led to World War I. He established his Italian home in Rome, where he quickly became one of the protagonists of the local musical life. He founded countless initiatives – some of them short-lived, but nonetheless highly significant – for the promotion of new music and its performance in Italy. Still, he was at least equally interested in the music of the past, which represented history and identity.

He toured extensively the US, where he was highly appreciated and about which he was a perceptive observer, reporting on the musical life of the States on European journals.

He continued to perform as a pianist, both as a soloist and as a member of the legendary Trio Italiano, to write (both music and essays), to be active as a member or Board member in many associations, and to teach extensively, both piano and composition.

In the summer of 1942, Casella’s health suddenly failed him, and for the remaining years of his life he was in constant pain, although he tried to maintain some concert engagements. In spite of his illness, however, his home was constantly the harbour of those who looked to him as to a reference point for Italy’s musical and cultural life. One of Casella’s last masterpieces is his Missa Solemnis Pro Pace (1944), where he gives voice to his religious feelings in dialogue with the tragedy of World War II.

Two among the most important piano works by Casella are recorded here. The first is his Sonatina op. 28, which has been defined as the icon, within Casella’s piano output, of his point of highest closeness to the world of Schoenberg (whose Pierrot Lunaire was premiered in Italy thanks to Casella’s tireless efforts). However, in this work from 1916 (i.e. shortly after Casella’s return to Italy), there are also many echoes from Stravinsky, Bartok, Ravel, and even Scriabin.

The deep care with which Casella shaped this work is evident in the lengthy instructions to the performer he provides in the first edition: «the execution of this little work can only be done with perfect consciousness of all the secrets of the modern pedal, and consequently knowing how wonderful and peculiar a poetry can be expected through a complex, very high ‘pedalistic’ registration. For these indications are superfluous; the performer will understand me without doubt. However, here and there, I thought it useful to guide the performer, compromise certain sounds that I hold dear».

It is in fact Casella’s most progressive work, where reminiscences from the style and works of the great modern composers are ceaselessly found, albeit in dialogue with the composer’s own personality.

Both this Sonatina and the Sinfonia, Arioso e Toccata are reminiscent of the Sonata form, and are the only Sonatas completed by the composer. The style of this work unavoidably suggests parallels with the political situation in the surrounding European countries. In spite of the diminutive title, it is one of Casella’s most demanding piano works, as concerns performing technique, aesthetical perspective, and interpretive traits. This work also mirrors the difficult moment Casella was living – as a citizen of a country at war, as a recently returned “outsider”, as a person of culture and conscience.

This Sonatina underwent a rather complex compositional process, during which it lost a Preludio allegretto, which would later be published as the second of the Deux contrastes op. 31.

Similar to the Sonatina op. 28, also the Sinfonia, Arioso e Toccata is a “collage of themes”, although in the earlier work the various themes seem to have been collated more tightly. In spite of this, memories and suggestions from the first movement are found and recur throughout the work. Still, it is a challenge for the interpreter to sustain the work’s narrative during its whole length.

The most obvious inspiration for this work came to Casella from Beethoven’s last Piano Sonata, op. 111. This inspiration regards both direct allusions, and the work’s structure. Casella’s admiration for Beethoven was transparent and took a variety of forms, including extensive instructive editing. The work’s title, furthermore, unavoidably brings to mind the great piano “triptychs” by César Franck. Possibly, these fascinating allusions to the “first of the Romantics” (as Casella considered Beethoven) and to one of the last representatives of Romanticism were intended to dispel the aura of anti-Romanticism which was preventing Casella’s full acceptance within the Italian musical scene.

The encounter with Casella was fundamental for the musical and human development of Goffredo Petrassi. Petrassi would recall that he had known Casella long before Casella could get to know him; and Casella’s influence on Petrassi is particularly evident precisely in the Partita. Furthermore, Casella’s interest in the music of both the past and the future was crucial for the young Petrassi.

Similar to Casella, also Petrassi lacked regular schooling, but their respective backgrounds were very different. Instead of Casella’s high-class and high-cultivated milieu, Petrassi came from a very modest household, and his formal education was very limited. However, being highly curious and interested in the spirituality of culture, Petrassi studied throughout his life, becoming a person of really noteworthy preparation. Petrassi had received his first musical education as a choirboy; that experience brought him a little income – which was very welcome given the situation of his family – but, most importantly, first-hand knowledge of the great Renaissance polyphonic repertoire.

As the young Petrassi was working at a music shop, a professor of piano of the Conservatory of Rome noticed him and invited him to study at the prestigious institution. Already before beginning his formal education, however, Petrassi had composed some important works, including the Partita recorded here. Indeed, Petrassi’s compositional output does not include many piano works, but this is compensated by their high musical and technical quality. This homage to the world of Baroque music, in four movements, is firmly rooted within the Classical tradition. The three pieces of Oh, les beaux jours were composed during wartime (1941-3) and later elaborated in a modified form in 1976. In their definitive shape they were composed for, and dedicated to, pianist Lya De Barberiis, one of Casella’s favourite students and a longtime champion of new music. Petrassi sent her the manuscript inviting her comments, since he did not feel particularly confident when writing for the piano. When she retouched a few details, and then played the work for him, he said: “Lya, you don’t play what I wrote, but what I thought!”.

The last piece in this recording is the exceedingly famous La Valse by Maurice Ravel. Here the connection with Casella is once more very clear, because Ravel and Casella premiered together the piano duet version of La Valse. The piece had originated as an idea through which Ravel had initially intended to pay homage to Vienna (in fact it was to be titled either Wien or Vienne). Later, legendary choreographer Diaghilev asked him to write a ballet score evoking the luxury and fascination of fin-de-siècle Vienna. However, the result did not correspond to Diaghilev’s expectations. Not without reason, he defined Ravel’s composition as a “portrait of a ballet” rather than a ballet proper. But this outraged Ravel, and ended their friendship. In spite of this, La Valse has been set to dance many times, and, in its concert form, has acquired extraordinary fame in the versions for solo piano, for piano duet, and for orchestra.

Therefore, the complete album allows us an experience of the fecund and creative atmosphere of those years, and to deduce the crucial role played by Casella as a protagonist of the intellectual and cultural life of his time. And, of course, to savour wonderful musical pieces which are, frequently, less known than they would deserve.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads