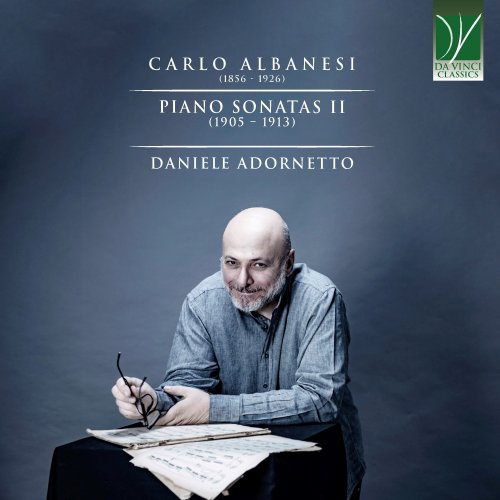

Daniele Adornetto - Carlo Albanesi: Piano Sonatas II (1905 - 1913) (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Daniele Adornetto

- Title: Carlo Albanesi: Piano Sonatas II (1905 - 1913)

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:57:01

- Total Size: 165 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Piano Sonata in B-Flat Minor, No.4: I. Allegro Maestoso

02. Piano Sonata in B-Flat Minor, No.4: II. Andante

03. Piano Sonata in B-Flat Minor, No.4: III. Finale - Allegro risoluto ed energico

04. Sonata in C Major: I. Con movimento, ma quasi solenne

05. Sonata in C Major: II. Scherzo - Presto

06. Sonata in C Major: III. Andante quasi Romanza - Cantabile sostenuto

07. Sonata in C Major: IV. Finale - Allegro marziale

In the nineteenth century, in Naples, one of the main centers of southern Italy, instrumental music was widely cultivated; there, the appreciation of instrumental and chamber music from other European countries was very common. In that city was born, on October 22nd, 1856, the protagonist of this Da Vinci Classics album.

Carlo Albanesi was the son of Luigi (1821-1897), who, in turn, came from a family of artists: his father had been a refined miniaturist and had taught him painting. After his family moved from their native Rome to Naples, Luigi found his vocation in music, learning piano and composition. He was particularly appreciated as a piano pedagogue, but his compositional output includes valuable works in the sacred field (motets, Masses and oratories) and in that of instrumental music (among which a curious Elegia a Garibaldi, paying homage to the celebrated Risorgimento hero).

At the time of Carlo’s birth, Naples was a real hotbed of musical culture, particularly as concerns instrumental music and specifically piano playing. The main figures of this piano Renaissance were Ferdinando Bonamici, Costantino Palumbo, Nicolò van Westerhout, Alfonso Rendano, Giuseppe Buonamici, Francesco Sangalli, Giovanni Rinaldi and Beniamino Cesi. Cesi, who would become one of the leading figures in the unified Peninsula as concerns piano playing, had been a student of Luigi Albanesi. Later, he also studied under the guidance of the great Sigismund Thalberg, who substantially favoured the establishment of a Neapolitan piano school during his stay in Posillipo (1858-71).

The repertoires practised and written by many of these musicians were still indebted to the operatic world; however, many of them were also among the earliest promoters of works such as the Well-Tempered Clavier in Italy.

Luigi’s son, Carlo, began his musical education under the guidance of his father. He also studied harmony and composition with Sabino Falconi. Carlo soon attracted the attention of the Neapolitan audience performing acclaimed concerts and recitals in his hometown. His debut took place at the time when several music societies were blossoming in the city; among them, the “Circolo Bonamici”, founded by pianist and pedagogue Fernando Bonamici, and the “Società Filarmonica”. The former institution was probably the first focusing specifically on piano music, and fostering it to a high level; the latter was to affirm itself as the first major concert society in Naples.

Having established his fame in Naples, Carlo decided to broaden his horizons and to seek fortune and further musical refinement outside the Peninsula. At first, in 1878, he moved to Paris, where he played numerous recitals to great acclaim. Four years later, in 1882, and following the advice of Francesco Paolo Tosti (1846-1916), the celebrated composer of Italian vocal chamber music, he settled in London, where his fame as a pianist and composer increased steadily.

An echo of his London debut is provided by Thomas Lamb Phipson, who, in his Confessions of a Violinist (1902), narrates: “The eminent professor of the piano, Carlo Albanesi, much patronised by royalty and the nobility of England, came to London, from Naples, with a letter of introduction to my sister […]. We gave him his first concert at the Putney Assembly Rooms on the 8th December 1882, at very short notice, and thus enabled him to earn the first £10-note he ever made in this country. His playing was most effective; by its delicacy and expressive cantabile it was, and is still, unsurpassable. Besides this, he was a man of most prepossessing appearance and manners. He told me that, in Naples, his father had so many pupils that he could only attend to him (Carlo) in the morning whilst he was being shaved. At this concert he had a little mute piano in the artists’ room on which he exercised his fingers. He also used it when travelling in a railway carriage. […] This concert brought him a good number of admirers”.

The increasing fame of Albanesi is witnessed by a review, dated August 1st, 1888, on the magazine The Theatre: “In the grace, delicacy and refinement of his playing, Signor Albanesi more than confirmed the favourable opinion so often expressed in the pages of «The Theatre» with respect to the executant merits of the handsome young Neapolitan, and amply sustained his reputation of a fertile, ingenious composer by introducing to the public three of his newest pianoforte works […], all of which bear the stamp of a thoughtful and highly cultivated musical intelligence”.

For the following ten years, indeed, Albanesi performed and taught unceasingly, whilst also pursuing his activity as a composer. In 1893 he was offered a prestigious job as a piano professor at the Royal Academy of Music, on the chair that had been Thomas Wingham’s. Albanesi would maintain this role until his death.

Three years later, Albanesi married a British author, Effie Adelaide Rowlands; the couple had two daughters, Eva Olimpia Maria (born in 1897) and Margherita Cecilia Brigida Lucia Maria. Born in 1899 and prematurely died in 1923, Margherita would obtain some fame as an actress under the name of Meggie Albanesi; her sister married in 1927 and, in 1948, settled in South Africa. The family lived in a beautiful home in central London, at 3 Gloucester Terrace in Hyde Park.

The prestige achieved by Albanesi in London is testified by the nobility which sought his lessons: he taught, among others, Crown Princess of Sweden and her sister, Princess Patricia of Connaught, the Duchess Marie of Saxe-Coburg and the Duchess Paul of Mecklenburgh. In turn, as a token of his value, Albanesi was knighted, as a Chevalier of the Crown of Italy; he was also a member of the London Philharmonic Society, and his services were often requested as an examiner at the Dublin Royal Academy of Music. Along with aristocrats, his students also included gifted musicians such as composer Mary Lucas. As a testimony of his gifts as a pedagogue, his published Exercises for Fingering, dating from the early 1900s, were in continuing demand and are still being reprinted and employed for piano teaching.

Albanesi’s compositional output includes symphonic music, chamber works (such as a string quartet and a trio for piano and strings) and compositions in other genres; however, he is best remembered for his piano music. In particular, this includes his Six Piano Sonatas, five of which survived until present-day. They belong in a relatively small but qualitatively conspicuous repertoire of “Italian” piano sonatas of the nineteenth century. Among the composers who ventured in this field are Romaniello, Del Valle De Paz, Westerhout, Frugatta, and Alessandro Longo.

Albanesi’s B-flat-minor Sonata is dedicated to Ernesto Consolo, a concert pianist, teacher, and composer, and it was issued in 1905. It obtained immediate success: a performance by pianist York Bowen at Aeolian Hall was greeted on the pages of the Athenaeum as a “work […] contain[ing] pleasing material, sound workmanship, and writing grateful to a pianist”, whilst the Musical Times hailed it as “a refined and graceful work”. Another later performance, by Hooper Brewster-Jones at the Royal College of Music earned him such applause that he had to return on stage six times.

The Sonata in B-flat minor is a Romantic work that fully explores the keyboard’s expressive and technical possibilities. The first movement, Allegro maestoso, opens with a powerful dotted-octave theme, followed by a flowing triplet passage and an expressive secondary theme in D-flat major. However, syncopations suggest an underlying unrest, which emerges in the development. A pleading motif in the right hand becomes a central element, shaping the movement’s expressive tension. The recapitulation builds to a monumental climax, ending in a glorious B-flat major flourish.

The second movement, Andante in G-flat major, follows a three-part form. The opening presents a contemplative atmosphere, weaving a triplet third motif into a dotted martial accompaniment. A dramatic middle section in D major builds a climax before the main theme returns in ornamented form, reaching a passionate peak before a soothing coda.

The finale, Allegro risoluto ed energico, is a rondo in 6/8 time, driven by an ostinato staccato motif. Contrasting sections in major introduce a playful element that gradually builds in intensity, leading back to the ostinato theme and to a spectacular ending.

Carlo Albanesi’s Piano Sonata No. 6 in C major (1913), dedicated to Michele Esposito, was his final sonata and one he performed publicly.

The opening Con movimento, ma quasi solenne introduces a solemn, dotted-rhythm theme, contrasted by lyrical secondary ideas and dramatic development in a minor key. The Scherzo in A minor (3/8) is lively and syncopated, with an ironic waltz and a fascinating middle section in F major. The Andante quasi Romanza in F major (Cantabile sostenuto) is prayerful and contemplative, with delicate semiquaver textures. The Finale (Allegro marziale) revisits earlier themes in an energetic 6/8 motion, culminating in a virtuosic, cascading coda in C major.

Albanesi’s compositional style is pronouncedly Romantic, and indulges in rich virtuoso writing; its technical palette includes arpeggios, scales, octaves, double thirds and sixths, bearing witness to the composer’s technical proficiency.

Even though it was argued that instrumental music did not belong in the really “Italian” music, and in spite of Albanesi’s long stay in England, his themes are Italian through and through; this is particularly evident in the form taken by his melodic phrases, especially in the slow movements. This may mirror Albanesi’s friendship with Tosti, but also his own genuine and personal expressive vein.

His piano scoring is indebted to Chopin’s (and, indeed, the Royal Academy would establish a Chopin Prize to honour Albanesi’s memory), but also to Brahms and Tchaikovsky; the grandioso style it reveals is particularly well-suited for concert performance and for the recital stage. In the words of the interpreter of this Da Vinci album, his music “accompanies and takes us by hand, at times forcefully, at time caressingly; the piano remains its great protagonist, bearing witness to Carlo Albanesi’s entire life”.

01. Piano Sonata in B-Flat Minor, No.4: I. Allegro Maestoso

02. Piano Sonata in B-Flat Minor, No.4: II. Andante

03. Piano Sonata in B-Flat Minor, No.4: III. Finale - Allegro risoluto ed energico

04. Sonata in C Major: I. Con movimento, ma quasi solenne

05. Sonata in C Major: II. Scherzo - Presto

06. Sonata in C Major: III. Andante quasi Romanza - Cantabile sostenuto

07. Sonata in C Major: IV. Finale - Allegro marziale

In the nineteenth century, in Naples, one of the main centers of southern Italy, instrumental music was widely cultivated; there, the appreciation of instrumental and chamber music from other European countries was very common. In that city was born, on October 22nd, 1856, the protagonist of this Da Vinci Classics album.

Carlo Albanesi was the son of Luigi (1821-1897), who, in turn, came from a family of artists: his father had been a refined miniaturist and had taught him painting. After his family moved from their native Rome to Naples, Luigi found his vocation in music, learning piano and composition. He was particularly appreciated as a piano pedagogue, but his compositional output includes valuable works in the sacred field (motets, Masses and oratories) and in that of instrumental music (among which a curious Elegia a Garibaldi, paying homage to the celebrated Risorgimento hero).

At the time of Carlo’s birth, Naples was a real hotbed of musical culture, particularly as concerns instrumental music and specifically piano playing. The main figures of this piano Renaissance were Ferdinando Bonamici, Costantino Palumbo, Nicolò van Westerhout, Alfonso Rendano, Giuseppe Buonamici, Francesco Sangalli, Giovanni Rinaldi and Beniamino Cesi. Cesi, who would become one of the leading figures in the unified Peninsula as concerns piano playing, had been a student of Luigi Albanesi. Later, he also studied under the guidance of the great Sigismund Thalberg, who substantially favoured the establishment of a Neapolitan piano school during his stay in Posillipo (1858-71).

The repertoires practised and written by many of these musicians were still indebted to the operatic world; however, many of them were also among the earliest promoters of works such as the Well-Tempered Clavier in Italy.

Luigi’s son, Carlo, began his musical education under the guidance of his father. He also studied harmony and composition with Sabino Falconi. Carlo soon attracted the attention of the Neapolitan audience performing acclaimed concerts and recitals in his hometown. His debut took place at the time when several music societies were blossoming in the city; among them, the “Circolo Bonamici”, founded by pianist and pedagogue Fernando Bonamici, and the “Società Filarmonica”. The former institution was probably the first focusing specifically on piano music, and fostering it to a high level; the latter was to affirm itself as the first major concert society in Naples.

Having established his fame in Naples, Carlo decided to broaden his horizons and to seek fortune and further musical refinement outside the Peninsula. At first, in 1878, he moved to Paris, where he played numerous recitals to great acclaim. Four years later, in 1882, and following the advice of Francesco Paolo Tosti (1846-1916), the celebrated composer of Italian vocal chamber music, he settled in London, where his fame as a pianist and composer increased steadily.

An echo of his London debut is provided by Thomas Lamb Phipson, who, in his Confessions of a Violinist (1902), narrates: “The eminent professor of the piano, Carlo Albanesi, much patronised by royalty and the nobility of England, came to London, from Naples, with a letter of introduction to my sister […]. We gave him his first concert at the Putney Assembly Rooms on the 8th December 1882, at very short notice, and thus enabled him to earn the first £10-note he ever made in this country. His playing was most effective; by its delicacy and expressive cantabile it was, and is still, unsurpassable. Besides this, he was a man of most prepossessing appearance and manners. He told me that, in Naples, his father had so many pupils that he could only attend to him (Carlo) in the morning whilst he was being shaved. At this concert he had a little mute piano in the artists’ room on which he exercised his fingers. He also used it when travelling in a railway carriage. […] This concert brought him a good number of admirers”.

The increasing fame of Albanesi is witnessed by a review, dated August 1st, 1888, on the magazine The Theatre: “In the grace, delicacy and refinement of his playing, Signor Albanesi more than confirmed the favourable opinion so often expressed in the pages of «The Theatre» with respect to the executant merits of the handsome young Neapolitan, and amply sustained his reputation of a fertile, ingenious composer by introducing to the public three of his newest pianoforte works […], all of which bear the stamp of a thoughtful and highly cultivated musical intelligence”.

For the following ten years, indeed, Albanesi performed and taught unceasingly, whilst also pursuing his activity as a composer. In 1893 he was offered a prestigious job as a piano professor at the Royal Academy of Music, on the chair that had been Thomas Wingham’s. Albanesi would maintain this role until his death.

Three years later, Albanesi married a British author, Effie Adelaide Rowlands; the couple had two daughters, Eva Olimpia Maria (born in 1897) and Margherita Cecilia Brigida Lucia Maria. Born in 1899 and prematurely died in 1923, Margherita would obtain some fame as an actress under the name of Meggie Albanesi; her sister married in 1927 and, in 1948, settled in South Africa. The family lived in a beautiful home in central London, at 3 Gloucester Terrace in Hyde Park.

The prestige achieved by Albanesi in London is testified by the nobility which sought his lessons: he taught, among others, Crown Princess of Sweden and her sister, Princess Patricia of Connaught, the Duchess Marie of Saxe-Coburg and the Duchess Paul of Mecklenburgh. In turn, as a token of his value, Albanesi was knighted, as a Chevalier of the Crown of Italy; he was also a member of the London Philharmonic Society, and his services were often requested as an examiner at the Dublin Royal Academy of Music. Along with aristocrats, his students also included gifted musicians such as composer Mary Lucas. As a testimony of his gifts as a pedagogue, his published Exercises for Fingering, dating from the early 1900s, were in continuing demand and are still being reprinted and employed for piano teaching.

Albanesi’s compositional output includes symphonic music, chamber works (such as a string quartet and a trio for piano and strings) and compositions in other genres; however, he is best remembered for his piano music. In particular, this includes his Six Piano Sonatas, five of which survived until present-day. They belong in a relatively small but qualitatively conspicuous repertoire of “Italian” piano sonatas of the nineteenth century. Among the composers who ventured in this field are Romaniello, Del Valle De Paz, Westerhout, Frugatta, and Alessandro Longo.

Albanesi’s B-flat-minor Sonata is dedicated to Ernesto Consolo, a concert pianist, teacher, and composer, and it was issued in 1905. It obtained immediate success: a performance by pianist York Bowen at Aeolian Hall was greeted on the pages of the Athenaeum as a “work […] contain[ing] pleasing material, sound workmanship, and writing grateful to a pianist”, whilst the Musical Times hailed it as “a refined and graceful work”. Another later performance, by Hooper Brewster-Jones at the Royal College of Music earned him such applause that he had to return on stage six times.

The Sonata in B-flat minor is a Romantic work that fully explores the keyboard’s expressive and technical possibilities. The first movement, Allegro maestoso, opens with a powerful dotted-octave theme, followed by a flowing triplet passage and an expressive secondary theme in D-flat major. However, syncopations suggest an underlying unrest, which emerges in the development. A pleading motif in the right hand becomes a central element, shaping the movement’s expressive tension. The recapitulation builds to a monumental climax, ending in a glorious B-flat major flourish.

The second movement, Andante in G-flat major, follows a three-part form. The opening presents a contemplative atmosphere, weaving a triplet third motif into a dotted martial accompaniment. A dramatic middle section in D major builds a climax before the main theme returns in ornamented form, reaching a passionate peak before a soothing coda.

The finale, Allegro risoluto ed energico, is a rondo in 6/8 time, driven by an ostinato staccato motif. Contrasting sections in major introduce a playful element that gradually builds in intensity, leading back to the ostinato theme and to a spectacular ending.

Carlo Albanesi’s Piano Sonata No. 6 in C major (1913), dedicated to Michele Esposito, was his final sonata and one he performed publicly.

The opening Con movimento, ma quasi solenne introduces a solemn, dotted-rhythm theme, contrasted by lyrical secondary ideas and dramatic development in a minor key. The Scherzo in A minor (3/8) is lively and syncopated, with an ironic waltz and a fascinating middle section in F major. The Andante quasi Romanza in F major (Cantabile sostenuto) is prayerful and contemplative, with delicate semiquaver textures. The Finale (Allegro marziale) revisits earlier themes in an energetic 6/8 motion, culminating in a virtuosic, cascading coda in C major.

Albanesi’s compositional style is pronouncedly Romantic, and indulges in rich virtuoso writing; its technical palette includes arpeggios, scales, octaves, double thirds and sixths, bearing witness to the composer’s technical proficiency.

Even though it was argued that instrumental music did not belong in the really “Italian” music, and in spite of Albanesi’s long stay in England, his themes are Italian through and through; this is particularly evident in the form taken by his melodic phrases, especially in the slow movements. This may mirror Albanesi’s friendship with Tosti, but also his own genuine and personal expressive vein.

His piano scoring is indebted to Chopin’s (and, indeed, the Royal Academy would establish a Chopin Prize to honour Albanesi’s memory), but also to Brahms and Tchaikovsky; the grandioso style it reveals is particularly well-suited for concert performance and for the recital stage. In the words of the interpreter of this Da Vinci album, his music “accompanies and takes us by hand, at times forcefully, at time caressingly; the piano remains its great protagonist, bearing witness to Carlo Albanesi’s entire life”.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads