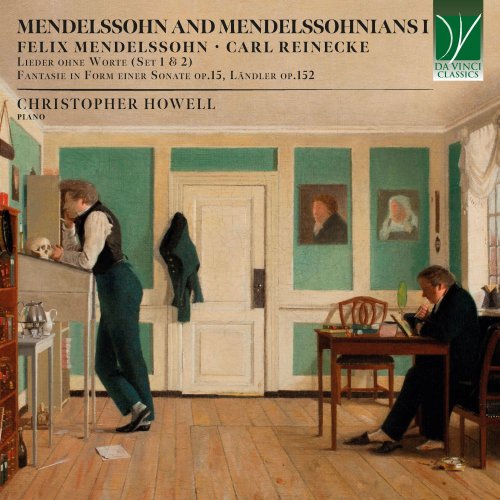

Christopher Howell - Mendelssohn and Mendelssohnians I (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Christopher Howell

- Title: Mendelssohn and Mendelssohnians I

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:08:28

- Total Size: 196 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 1, Andante con moto (Set 1)

02. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 2, Andante espressivo (Set 1)

03. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 3, Molto allegro e vivace (Set 1)

04. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 4, Moderato (Set 1)

05. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 5, Poco agitato (Set 1)

06. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 6, Venetianisches Gondellied (Set 1)

07. Fantasie in Form einer Sonate, Op. 15: No. 1, Allegro

08. Fantasie in Form einer Sonate, Op. 15: No. 2, Andante

09. Fantasie in Form einer Sonate, Op. 15: No. 3, Mazuarka: Molto vivace

10. Fantasie in Form einer Sonate, Op. 15: No. 4, Finale: Allegro

11. Ländler, Op. 152

12. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 1, Andante espressivo (Set 2)

13. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 2, Allegro di molto (Set 2)

14. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 3, Adagio non troppo (Set 2)

15. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 4, Agitato e con fuoco (Set 2)

16. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 5, Andante grazioso (Set 2)

17. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 6, Venetianisches Gondellied (Set 2)

This series aims to present four composers generally associated with the Mendelssohnian world, bookending each of them with two sets of Mendelssohn’s own Lieder ohne Worte. Paradoxically, the result may show how little they adopted either the master’s tone or his methods.

Carl Reinecke studied with Mendelssohn from 1843, as well as with Schumann and Liszt, though he was less drawn to the latter. For thirty-five years (1860-1895), he was conductor of Mendelssohn’s former stronghold, the Leipzig Gewandhaus. This was considerably after Mendelssohn’s time, but Reinecke was notoriously a conservative. The earlier of the two works recorded here, the Fantasie in Form einer Sonate op. 15, was published the year after Mendelssohn’s death. Yet, whatever else it may be, a Mendelssohn clone it is not.

The first thing to strike us is the boldness – or foolhardiness – of the young composer in dominating his first movement with a motto theme that seems a timid echo, upside down and with chords added, of the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. The second impression is that the model, or at least the opening gambit, derives from Schubert’s final B flat sonata. Reinecke makes the same use of thematic cells separated by pregnant pauses. The music then bursts into impetuous movement, only to be interrupted by the motto theme. The repeated chords of the second subject are also Schubertian. It will have become evident by now, however, that Reinecke’s method bears no resemblance to that of Schubert, let alone Mendelssohn or Schumann, since he is relying, not on extended melodies or thematic development, but on brief, often highly memorable, melodic cells that are then juggled and shuffled to create a sort of mosaic. True to this idea, in place of the development section of the traditional sonata form, he writes a completely new theme, offering the first sustained paragraph heard so far. This extremely fine page is one of the moments where we can forgive Reinecke all his oddities. After a shortened recapitulation of the first section, the composer then brings back this “third” subject, with the triplets of the motto theme accompanying it. The chordal second subject, combined with further reminiscences of the third, is reserved for a coda.

If the first movement may arouse sympathy and perplexity in equal measure, the second must surely arouse no doubts. The pianist who regrets that Bruckner wrote no piano music might find solace in this gravely passionate movement. Here, at last, Reinecke gives us long, sustained paragraphs. After reminiscences of the triplet motto theme, the second subject is no less memorable than the first. Towards the end, the two are combined in a passage of exceptional beauty.

After two extended movements, Reinecke now contradicts our expectations by writing two extremely short ones. His Mazurka sounds as little like Chopin as a Mazurka can. Rather, if Mendelssohn had ever written a Mazurka, perhaps it would have sounded something like this.

The opening idea of the finale sounds like pure Schumann – replete with the Clara theme. This leads to a rising chromatic motif, suggestive of Liszt or even Berlioz, especially when Reinecke confronts it with its descending inversion in the development – though any attempts to brew up a Witches’ Sabbath quickly give way to a more lyrical continuation. The work ends with a delicate reminiscence of the Schumann theme.

In this Fantasie, Reinecke seems almost deliberately to invite ridicule. I can only say that the necessary time spent in its company to perform it from memory in the studio convinced me that the composer’s underlying sincerity makes it add up into a curiously personal statement, with a moving slow movement at its core.

Those unconvinced should find plenty to enjoy in the rather later (1878) Ländler op.152. While the title may lead us to expect a nostalgic look at Schubert, the effect, with its delicate waltz-inflections, looks ahead to Léhar. The seven pieces follow without a break, leading to a coda based on reminiscences of nos. 1, 5, 3 and 4. The second part of no. 4 recalls, whether consciously or not, the chromatic theme from the finale of the Fantasie. In the middle of the doleful no. 5, the pianist seemingly forgets he is accompanying dancers and embarks on a close cousin of Schubert’s E flat Impromptu. The quirky no. 6 is an inverted canon that might have amused Webern, while the second page of no. 7 has an augmented canon that, far from sounding academic, suggests a rapturous duet between soprano and tenor. A minor work, doubtless, but a very attractive one.

The sheer ubiquity of Mendelssohn’s Lieder ohne Worte – in the drawing room when amateur music making was common and in teaching syllabuses to this day – has tended to give the impression that they are in some way inferior products. By taking them for granted, we risk losing sight of Mendelssohn’s originality in creating pieces that sound vocal yet are not – you could not really sing many of them – and a piano idiom that is distinct from that of his contemporaries, even Schumann, with whom he had the greatest affinity. Or of his uncanny ability to suggest picturesque ideas and moods that cannot quite be pinned down. He did give a few of the pieces titles – mainly limiting himself to those that could be guessed at anyway, such as the three “Gondola Songs”. Victorian admirers rushed to fill the gaps and older editions may still be found with titles that risk being reductive – if “Fleecy Clouds” evokes that at all, does it evoke only that (Mendelssohn marked it to be played Sehr innig)? If a piece suggests “Consolation” or “Resignation” or “Hope” to one person, might it not suggest something quite different to another? Best, then, to set aside such images, or at least keep them for oneself, and enjoy the range of mood and invention on offer.

Mendelssohn’s combination of romanticism and classicism presents the pianist with a particular challenge. His melodies in themselves seem to call for a freely expressive rubato style, but they are more often than not accompanied by figures that require the steadiness of an Alberti bass. To remain with the pieces on this disc, the constant semi-quaver movement in op. 19 no. 1 has a hypnotic quality all of its own depending upon its Bach-like constancy. Likewise the triplet movement of op. 30 no. 1. Nor can the gondolier expect the waves of the lagoon to adapt themselves to the rubato of his songs. On the other hand, it would be unthinkable to straight-jacket these highly vocal melodies to a metronomic accompaniment. The performer must seek to make his speedings, his slowings and his hesitations sufficiently smoothly as to give space to the melody without interrupting the flow.

The idea has got about that Mendelssohn’s world is an essentially comfortable one, and some performers have preferred to smooth out his often abrupt and disturbing dynamic markings to fit this view. He can on occasion be emotionally disquieting. If the Victorians liked to call op. 19 no. 1 “Remembrance” – and its passions are expressed with a veneer of serenity – they might have called op. 19 no. 2 “Unforgotten”. Its spare textures and harsh unrest find no solution, but rather disappear into a black hole at the end. Op. 30 no. 4 hurtles to its minor key dénouement though op. 30 no. 2, as obsessive as anything by Rachmaninov for most of its length, bursts into the major key at the end. Op. 19 no. 5 is marked Poco agitato in most editions, though some have Piano agitato. The 1915 Schirmer edition “corrected” this to Presto agitato, which is how it is usually played, though the quaver undercurrent registers better at a less than breakneck tempo.

Two numbers in these two sets come closer to the pictorial genre piece. Op. 19 no. 3 is generally known as “Hunting Song” and this seems plausible, though ecologists may prefer to hear it is an abstract burst of exuberance. “The Rivulet” has stuck as a title for op. 30 no. 5, but would not “The Bumble-Bee” do equally well?

One Mendelssohnian-type has proved uncomfortable in the 20th and 21st century – the chorale-like piece enclosed by a rippling introduction and coda. A bowdlerized version of op. 30 no. 3 is actually sung as a hymn in some churches. One of the greatest 20th century pianists performed op. 19 otherwise complete, but omitting no. 4. These pieces reveal their depths if treated as personal meditations, free of religious trappings.

01. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 1, Andante con moto (Set 1)

02. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 2, Andante espressivo (Set 1)

03. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 3, Molto allegro e vivace (Set 1)

04. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 4, Moderato (Set 1)

05. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 5, Poco agitato (Set 1)

06. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 19b: No. 6, Venetianisches Gondellied (Set 1)

07. Fantasie in Form einer Sonate, Op. 15: No. 1, Allegro

08. Fantasie in Form einer Sonate, Op. 15: No. 2, Andante

09. Fantasie in Form einer Sonate, Op. 15: No. 3, Mazuarka: Molto vivace

10. Fantasie in Form einer Sonate, Op. 15: No. 4, Finale: Allegro

11. Ländler, Op. 152

12. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 1, Andante espressivo (Set 2)

13. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 2, Allegro di molto (Set 2)

14. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 3, Adagio non troppo (Set 2)

15. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 4, Agitato e con fuoco (Set 2)

16. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 5, Andante grazioso (Set 2)

17. 6 Lieder ohne Worte, Op. 30: No. 6, Venetianisches Gondellied (Set 2)

This series aims to present four composers generally associated with the Mendelssohnian world, bookending each of them with two sets of Mendelssohn’s own Lieder ohne Worte. Paradoxically, the result may show how little they adopted either the master’s tone or his methods.

Carl Reinecke studied with Mendelssohn from 1843, as well as with Schumann and Liszt, though he was less drawn to the latter. For thirty-five years (1860-1895), he was conductor of Mendelssohn’s former stronghold, the Leipzig Gewandhaus. This was considerably after Mendelssohn’s time, but Reinecke was notoriously a conservative. The earlier of the two works recorded here, the Fantasie in Form einer Sonate op. 15, was published the year after Mendelssohn’s death. Yet, whatever else it may be, a Mendelssohn clone it is not.

The first thing to strike us is the boldness – or foolhardiness – of the young composer in dominating his first movement with a motto theme that seems a timid echo, upside down and with chords added, of the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. The second impression is that the model, or at least the opening gambit, derives from Schubert’s final B flat sonata. Reinecke makes the same use of thematic cells separated by pregnant pauses. The music then bursts into impetuous movement, only to be interrupted by the motto theme. The repeated chords of the second subject are also Schubertian. It will have become evident by now, however, that Reinecke’s method bears no resemblance to that of Schubert, let alone Mendelssohn or Schumann, since he is relying, not on extended melodies or thematic development, but on brief, often highly memorable, melodic cells that are then juggled and shuffled to create a sort of mosaic. True to this idea, in place of the development section of the traditional sonata form, he writes a completely new theme, offering the first sustained paragraph heard so far. This extremely fine page is one of the moments where we can forgive Reinecke all his oddities. After a shortened recapitulation of the first section, the composer then brings back this “third” subject, with the triplets of the motto theme accompanying it. The chordal second subject, combined with further reminiscences of the third, is reserved for a coda.

If the first movement may arouse sympathy and perplexity in equal measure, the second must surely arouse no doubts. The pianist who regrets that Bruckner wrote no piano music might find solace in this gravely passionate movement. Here, at last, Reinecke gives us long, sustained paragraphs. After reminiscences of the triplet motto theme, the second subject is no less memorable than the first. Towards the end, the two are combined in a passage of exceptional beauty.

After two extended movements, Reinecke now contradicts our expectations by writing two extremely short ones. His Mazurka sounds as little like Chopin as a Mazurka can. Rather, if Mendelssohn had ever written a Mazurka, perhaps it would have sounded something like this.

The opening idea of the finale sounds like pure Schumann – replete with the Clara theme. This leads to a rising chromatic motif, suggestive of Liszt or even Berlioz, especially when Reinecke confronts it with its descending inversion in the development – though any attempts to brew up a Witches’ Sabbath quickly give way to a more lyrical continuation. The work ends with a delicate reminiscence of the Schumann theme.

In this Fantasie, Reinecke seems almost deliberately to invite ridicule. I can only say that the necessary time spent in its company to perform it from memory in the studio convinced me that the composer’s underlying sincerity makes it add up into a curiously personal statement, with a moving slow movement at its core.

Those unconvinced should find plenty to enjoy in the rather later (1878) Ländler op.152. While the title may lead us to expect a nostalgic look at Schubert, the effect, with its delicate waltz-inflections, looks ahead to Léhar. The seven pieces follow without a break, leading to a coda based on reminiscences of nos. 1, 5, 3 and 4. The second part of no. 4 recalls, whether consciously or not, the chromatic theme from the finale of the Fantasie. In the middle of the doleful no. 5, the pianist seemingly forgets he is accompanying dancers and embarks on a close cousin of Schubert’s E flat Impromptu. The quirky no. 6 is an inverted canon that might have amused Webern, while the second page of no. 7 has an augmented canon that, far from sounding academic, suggests a rapturous duet between soprano and tenor. A minor work, doubtless, but a very attractive one.

The sheer ubiquity of Mendelssohn’s Lieder ohne Worte – in the drawing room when amateur music making was common and in teaching syllabuses to this day – has tended to give the impression that they are in some way inferior products. By taking them for granted, we risk losing sight of Mendelssohn’s originality in creating pieces that sound vocal yet are not – you could not really sing many of them – and a piano idiom that is distinct from that of his contemporaries, even Schumann, with whom he had the greatest affinity. Or of his uncanny ability to suggest picturesque ideas and moods that cannot quite be pinned down. He did give a few of the pieces titles – mainly limiting himself to those that could be guessed at anyway, such as the three “Gondola Songs”. Victorian admirers rushed to fill the gaps and older editions may still be found with titles that risk being reductive – if “Fleecy Clouds” evokes that at all, does it evoke only that (Mendelssohn marked it to be played Sehr innig)? If a piece suggests “Consolation” or “Resignation” or “Hope” to one person, might it not suggest something quite different to another? Best, then, to set aside such images, or at least keep them for oneself, and enjoy the range of mood and invention on offer.

Mendelssohn’s combination of romanticism and classicism presents the pianist with a particular challenge. His melodies in themselves seem to call for a freely expressive rubato style, but they are more often than not accompanied by figures that require the steadiness of an Alberti bass. To remain with the pieces on this disc, the constant semi-quaver movement in op. 19 no. 1 has a hypnotic quality all of its own depending upon its Bach-like constancy. Likewise the triplet movement of op. 30 no. 1. Nor can the gondolier expect the waves of the lagoon to adapt themselves to the rubato of his songs. On the other hand, it would be unthinkable to straight-jacket these highly vocal melodies to a metronomic accompaniment. The performer must seek to make his speedings, his slowings and his hesitations sufficiently smoothly as to give space to the melody without interrupting the flow.

The idea has got about that Mendelssohn’s world is an essentially comfortable one, and some performers have preferred to smooth out his often abrupt and disturbing dynamic markings to fit this view. He can on occasion be emotionally disquieting. If the Victorians liked to call op. 19 no. 1 “Remembrance” – and its passions are expressed with a veneer of serenity – they might have called op. 19 no. 2 “Unforgotten”. Its spare textures and harsh unrest find no solution, but rather disappear into a black hole at the end. Op. 30 no. 4 hurtles to its minor key dénouement though op. 30 no. 2, as obsessive as anything by Rachmaninov for most of its length, bursts into the major key at the end. Op. 19 no. 5 is marked Poco agitato in most editions, though some have Piano agitato. The 1915 Schirmer edition “corrected” this to Presto agitato, which is how it is usually played, though the quaver undercurrent registers better at a less than breakneck tempo.

Two numbers in these two sets come closer to the pictorial genre piece. Op. 19 no. 3 is generally known as “Hunting Song” and this seems plausible, though ecologists may prefer to hear it is an abstract burst of exuberance. “The Rivulet” has stuck as a title for op. 30 no. 5, but would not “The Bumble-Bee” do equally well?

One Mendelssohnian-type has proved uncomfortable in the 20th and 21st century – the chorale-like piece enclosed by a rippling introduction and coda. A bowdlerized version of op. 30 no. 3 is actually sung as a hymn in some churches. One of the greatest 20th century pianists performed op. 19 otherwise complete, but omitting no. 4. These pieces reveal their depths if treated as personal meditations, free of religious trappings.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads