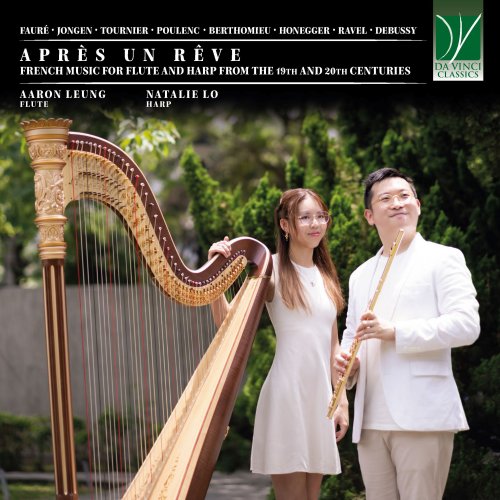

Aaron Leung, Natalie Lo - APRÈS UN RÊVE: French Music for Flute and Harp from the 19th and 20th Centuries (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Aaron Leung, Natalie Lo

- Title: APRÈS UN RÊVE: French Music for Flute and Harp from the 19th and 20th Centuries

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:45:56

- Total Size: 152 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Sicilienne, Op. 78

02. Danse Lente Pour Et Harpe, Op. 56

03. 2 Preludes Romantiques, Op. 17: No. 1, Tres lent

04. 2 Preludes Romantiques, Op. 17: No. 2, Allegro moderato

05. Un joueur de flûte berce les ruins

06. 5 Nuances: No. 1, Pathetico

07. 5 Nuances: No. 2, Lascivo

08. 5 Nuances: No. 3, Idyllic

09. 5 Nuances: No. 4, Exotico

10. 5 Nuances: No. 5, Dolcissimo

11. Danse de la chèvre

12. Pavane pour une infante defunte

13. Syrinx, L.129, L.129

14. Fantasie, Op. 79

15. Après un rêve, Op. 7: No. 1

Après un rêve, “after a dream”. What is left after a dream? A memory, often confused and blurred; some vague impressions, at times clearer but normally more emotional and affective than logical. The title of a song by Gabriel Fauré, transcribed for flute and harp in this Da Vinci Classics album, lends itself perfectly to become the title for this entire compilation.

The period between nineteenth and twentieth century was marked by a novel attention to the world of dreams. Sigmund Freud was elaborating and promoting his theory of psychanalysis; from that moment, even for those who did not embrace in full the psychoanalytic theory, dreams would become something different from what they used to be. They were considered as an open door onto a person’s innermost world; onto the obscure and dark, unknown forces which pull and push – according to Freud – the human beings’ behaviour and beliefs, their fears and hopes, their perspective on life and their affectivity.

But even though Freud was attempting (more or less successfully, to be sure) to give systematicity to the world of dreams, they still eluded, and keep eluding, all efforts at objectivity. Dreams remain something entirely private, whose details and fringes are intelligible only by the persons who live them, and frequently not even by them.

This tension between the fascination of the unknown, the attraction of the fantastic, the fear for obscurity, and the attempt to rule and govern this world by means of “science” is typical for the fin-de-siècle. In France, Impressionism has something of the fabric of which dreams are made: the “impressions” left on the viewer by the paintings of Monet, for instance, are as vague and as clear (at the same time) as those left by dreams. Symbolist poetry, even more evidently, is very close to the world of dreams. Here, as there, scraps of images, symbols, suggestions, are juxtaposed in a seemingly haphazard fashion. However, their “random” coexistence is meaningful and conveys a plethora of symbolic meanings, which words alone would never be able to transmit. Symbolic associations, just as dreams, are significant in a different fashion for different people; however, they also borrow from an inner deposit of archetypes (that the other father of psychanalysis, Carl Jung, would explore) which are common, at least in part, to all human beings.

And it is probably from musical archetypes that many works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album draw in turn. The flute and the harp, albeit in primitive forms, very different from modern concert instruments, are among the oldest musical instruments, and are found in most cultures worldwide. Blowing into a reed seems to be almost an instinct for curious human beings, as is plucking strings to make them vibrate. These musical “instincts” have generated these two foundational instruments, and many others derived from them.

And although musicologists may raise more than an eyebrow at some symbolic associations, it is undeniable that some musical archetypes and symbols are actually evoked by their sound. Harp and “water”, flute and “sky” are two of them. Why is it so? Arpeggios played on the harp have always been felt as reminiscent of fluid waves, like those of ponds or brooks. Flute sounds soar above all other instrumental textures, and suggest birdsong – the sounds of the inhabitants of the sky. Thus, the world of “dreams” and that of these two instruments have much in common, and are in a constant, fecund dialogue in the history of music.

Flying like a bird is an image evoked by the lyrics of Après un rêve, where a lover is attracted to the beloved just as by the dawn among the clouds; when he falls back into the dark night, having lost the illusion created by dreams, he appeals to the night for bringing him back the ephemeral bliss of the dream.

This song, one of the many written by Fauré, is probably his best known, and with reason; this version for flute and harp manages to bring to light some of its hidden meanings.

If Fauré closes the album with Après un rêve, his music also opens it with another concert favourite, the Sicilienne.

Its genesis had been complex. Its first version dates back from 1893, when Fauré composed drafts for incidental music for Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme. The production never got to the stage, and the already-composed works were left aside. Five years later, Fauré decided to resume some of them, and in particular what would become a Sicilienne for cello and piano. It was to become one of his most successful works. At the same time, he entrusted to Charles Koechlin, a gifted student of him, the task of orchestrating the piece; in this version, it was to be included within another theatrical production, i.e. that of Pelléas et Mélisande by Maeterlinck. It debuted in 1898, in London, under Faure’s baton. Here too the migration from the cello and piano duo to the flute and harp duo only adds a magical dimension to a classic of the concert scene.

Another work which epitomizes the figure and fame of its composer is the Danse lente by Joseph Jongen. He was a Belgian organist, composer and professor who, after his studies in his native land, completed his education with extensive stays throughout Europe: in Berlin (with d’Indy and Richard Strauss), in Munich, in Bayreuth, in Vienna, in Paris, and finally in Rome. He resided in Bruxelles and in London, and it was there (where he lived during World War I) that he composed the Danse lente, doubtlessly the best-known among the numerous chamber music pieces he wrote in his lifetime.

Also Marcel Tournier’s Deux Préludes were conceived with other instrumental forces in mind. The “harmonic” instrument, in fact, could be either a piano or a harp in the original version, but the “melodic” instrument was a violin in Tournier’s setting. A harpist and composer who studied at the Conservatory of Paris, he was a Prix-de-Rome laureate (just as was Jongen in the Belgian version of the same award). These Préludes perfectly fit within the romantic and dreamy atmosphere of this album. The first of them, Très lent, assigns to the “melodic” and “harmonic” instruments their typical roles: a long expressive tune played by the flute, and a rocking accompaniment in arpeggiated chords by the harp. The texture is not entirely different in the other Prélude, the Allegro moderato, but what changes here is the mood: a more obscure style, with echoes from the unknown, as if exploring both the luminous and the dark sides of the world of dreams.

Francis Poulenc was very far from the world of Romantic or Impressionist dreams; his music is Neo-classical and humorous, pointed and brilliant. His chamber music output is very abundant and includes works for a number of different ensembles, among which the very famous Flute Sonata, one of the highlights of the international flute repertoire.

In contrast with this, Un joueur de flute berce les ruines (“A Flute Player Lullabies the Ruins”) is a piece whose score was discovered only in 1997, and brought to fame and celebrity by Ransom Wilson, an American flutist. The title, which is in fact very suggestive and somewhat reminiscent of symbolist poetry, evokes a feeling of loss and nostalgia, but also the idea of death as a slumber, lulled by the flute. The work’s modal flair adds to its fascination and to the impression of antiquity and of remoteness.

Also for Marc Berthomieu the flute was an especially cherished instrument. He had studied at the Conservatory of Paris, and the main component of his professional activity as a musician took the form of teaching. However, he was also active in the field of music broadcasting (TV and radio). Reminiscences of the Romantic and Neoclassical era are found in his style, of which the Cinq Nuances are a beautiful representative. Throughout the composition, which consists of five movement with allusive and curious titles, the flute creates enthralling melodic lines, in which the taste for sound, for an instrumental belcanto, is discernible at every step. Though the centrepiece is called Idyllic, the impression of “idyll” characterizes rather deeply the entire collection and contributes to its success among flutists and harpists.

A very different style characterizes the Danse de la chèvre (Dance of the Goat) by Arthur Honegger. Originally written in 1921 for dancer Lysana, who performed in La Mauvaise Pensée by Sacha Derek, the piece was premiered in the same year and dedicated to René Le Roy. The piece represents both the tranquil alpine scenery and the bizarre movements of the mountain goat. In fact, the word “capricious” derives from the old Italian caprizare, i.e. to move as a goat; this piece, therefore, is a quintessential “capriccio”.

Still another contrast is represented by a very famous work by Maurice Ravel, which exists in a variety of forms. His Pavane pour une infante défunte, written in 1899 for solo piano and orchestrated by the composer in 1910, had originally been conceived as a homage to the Princesse of Polignac. It is an evocation of the solemnity and gravity of courtly dances in Baroque Spain, seen through the lens of a double exoticism: geographic (Spain) and historic (Baroque). It is also an implicit homage to Gabriel Fauré, who was Ravel’s teacher at the time and who had written a very famous Pavane in turn.

Syrinx is one of the best-known works for unaccompanied flute in music history. Written in 1913 by Claude Debussy and dedicated to Louis Fleury, it had been conceived in turn as incidental music for Psyché by Gabriel Mourey, a friend of Debussy. Similar to the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, the work is centered on the figure of the dying Pan, whose beloved Syrinx was transformed into reeds and then into the eponymous musical instrument.

Penultimate… but not least (the last piece has been discussed already), Fauré’s Fantaisie is still another classic of the flute repertoire. Written on a commission by Paul Taffanel, it was conceived as an exam piece for the flute graduates of the Conservatoire. Even though it is designed to test the performer’s skills in terms of both technique and expressivity, it is by no means a “scholastic” work. It is a short masterpiece which has fully earned the fame and success it still enjoys.

Together, the works recorded here invite the listener to a journey made of dreams and “after-dreams”, of scraps of fantasy and consciousness which will certainly capture the audience.

01. Sicilienne, Op. 78

02. Danse Lente Pour Et Harpe, Op. 56

03. 2 Preludes Romantiques, Op. 17: No. 1, Tres lent

04. 2 Preludes Romantiques, Op. 17: No. 2, Allegro moderato

05. Un joueur de flûte berce les ruins

06. 5 Nuances: No. 1, Pathetico

07. 5 Nuances: No. 2, Lascivo

08. 5 Nuances: No. 3, Idyllic

09. 5 Nuances: No. 4, Exotico

10. 5 Nuances: No. 5, Dolcissimo

11. Danse de la chèvre

12. Pavane pour une infante defunte

13. Syrinx, L.129, L.129

14. Fantasie, Op. 79

15. Après un rêve, Op. 7: No. 1

Après un rêve, “after a dream”. What is left after a dream? A memory, often confused and blurred; some vague impressions, at times clearer but normally more emotional and affective than logical. The title of a song by Gabriel Fauré, transcribed for flute and harp in this Da Vinci Classics album, lends itself perfectly to become the title for this entire compilation.

The period between nineteenth and twentieth century was marked by a novel attention to the world of dreams. Sigmund Freud was elaborating and promoting his theory of psychanalysis; from that moment, even for those who did not embrace in full the psychoanalytic theory, dreams would become something different from what they used to be. They were considered as an open door onto a person’s innermost world; onto the obscure and dark, unknown forces which pull and push – according to Freud – the human beings’ behaviour and beliefs, their fears and hopes, their perspective on life and their affectivity.

But even though Freud was attempting (more or less successfully, to be sure) to give systematicity to the world of dreams, they still eluded, and keep eluding, all efforts at objectivity. Dreams remain something entirely private, whose details and fringes are intelligible only by the persons who live them, and frequently not even by them.

This tension between the fascination of the unknown, the attraction of the fantastic, the fear for obscurity, and the attempt to rule and govern this world by means of “science” is typical for the fin-de-siècle. In France, Impressionism has something of the fabric of which dreams are made: the “impressions” left on the viewer by the paintings of Monet, for instance, are as vague and as clear (at the same time) as those left by dreams. Symbolist poetry, even more evidently, is very close to the world of dreams. Here, as there, scraps of images, symbols, suggestions, are juxtaposed in a seemingly haphazard fashion. However, their “random” coexistence is meaningful and conveys a plethora of symbolic meanings, which words alone would never be able to transmit. Symbolic associations, just as dreams, are significant in a different fashion for different people; however, they also borrow from an inner deposit of archetypes (that the other father of psychanalysis, Carl Jung, would explore) which are common, at least in part, to all human beings.

And it is probably from musical archetypes that many works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album draw in turn. The flute and the harp, albeit in primitive forms, very different from modern concert instruments, are among the oldest musical instruments, and are found in most cultures worldwide. Blowing into a reed seems to be almost an instinct for curious human beings, as is plucking strings to make them vibrate. These musical “instincts” have generated these two foundational instruments, and many others derived from them.

And although musicologists may raise more than an eyebrow at some symbolic associations, it is undeniable that some musical archetypes and symbols are actually evoked by their sound. Harp and “water”, flute and “sky” are two of them. Why is it so? Arpeggios played on the harp have always been felt as reminiscent of fluid waves, like those of ponds or brooks. Flute sounds soar above all other instrumental textures, and suggest birdsong – the sounds of the inhabitants of the sky. Thus, the world of “dreams” and that of these two instruments have much in common, and are in a constant, fecund dialogue in the history of music.

Flying like a bird is an image evoked by the lyrics of Après un rêve, where a lover is attracted to the beloved just as by the dawn among the clouds; when he falls back into the dark night, having lost the illusion created by dreams, he appeals to the night for bringing him back the ephemeral bliss of the dream.

This song, one of the many written by Fauré, is probably his best known, and with reason; this version for flute and harp manages to bring to light some of its hidden meanings.

If Fauré closes the album with Après un rêve, his music also opens it with another concert favourite, the Sicilienne.

Its genesis had been complex. Its first version dates back from 1893, when Fauré composed drafts for incidental music for Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme. The production never got to the stage, and the already-composed works were left aside. Five years later, Fauré decided to resume some of them, and in particular what would become a Sicilienne for cello and piano. It was to become one of his most successful works. At the same time, he entrusted to Charles Koechlin, a gifted student of him, the task of orchestrating the piece; in this version, it was to be included within another theatrical production, i.e. that of Pelléas et Mélisande by Maeterlinck. It debuted in 1898, in London, under Faure’s baton. Here too the migration from the cello and piano duo to the flute and harp duo only adds a magical dimension to a classic of the concert scene.

Another work which epitomizes the figure and fame of its composer is the Danse lente by Joseph Jongen. He was a Belgian organist, composer and professor who, after his studies in his native land, completed his education with extensive stays throughout Europe: in Berlin (with d’Indy and Richard Strauss), in Munich, in Bayreuth, in Vienna, in Paris, and finally in Rome. He resided in Bruxelles and in London, and it was there (where he lived during World War I) that he composed the Danse lente, doubtlessly the best-known among the numerous chamber music pieces he wrote in his lifetime.

Also Marcel Tournier’s Deux Préludes were conceived with other instrumental forces in mind. The “harmonic” instrument, in fact, could be either a piano or a harp in the original version, but the “melodic” instrument was a violin in Tournier’s setting. A harpist and composer who studied at the Conservatory of Paris, he was a Prix-de-Rome laureate (just as was Jongen in the Belgian version of the same award). These Préludes perfectly fit within the romantic and dreamy atmosphere of this album. The first of them, Très lent, assigns to the “melodic” and “harmonic” instruments their typical roles: a long expressive tune played by the flute, and a rocking accompaniment in arpeggiated chords by the harp. The texture is not entirely different in the other Prélude, the Allegro moderato, but what changes here is the mood: a more obscure style, with echoes from the unknown, as if exploring both the luminous and the dark sides of the world of dreams.

Francis Poulenc was very far from the world of Romantic or Impressionist dreams; his music is Neo-classical and humorous, pointed and brilliant. His chamber music output is very abundant and includes works for a number of different ensembles, among which the very famous Flute Sonata, one of the highlights of the international flute repertoire.

In contrast with this, Un joueur de flute berce les ruines (“A Flute Player Lullabies the Ruins”) is a piece whose score was discovered only in 1997, and brought to fame and celebrity by Ransom Wilson, an American flutist. The title, which is in fact very suggestive and somewhat reminiscent of symbolist poetry, evokes a feeling of loss and nostalgia, but also the idea of death as a slumber, lulled by the flute. The work’s modal flair adds to its fascination and to the impression of antiquity and of remoteness.

Also for Marc Berthomieu the flute was an especially cherished instrument. He had studied at the Conservatory of Paris, and the main component of his professional activity as a musician took the form of teaching. However, he was also active in the field of music broadcasting (TV and radio). Reminiscences of the Romantic and Neoclassical era are found in his style, of which the Cinq Nuances are a beautiful representative. Throughout the composition, which consists of five movement with allusive and curious titles, the flute creates enthralling melodic lines, in which the taste for sound, for an instrumental belcanto, is discernible at every step. Though the centrepiece is called Idyllic, the impression of “idyll” characterizes rather deeply the entire collection and contributes to its success among flutists and harpists.

A very different style characterizes the Danse de la chèvre (Dance of the Goat) by Arthur Honegger. Originally written in 1921 for dancer Lysana, who performed in La Mauvaise Pensée by Sacha Derek, the piece was premiered in the same year and dedicated to René Le Roy. The piece represents both the tranquil alpine scenery and the bizarre movements of the mountain goat. In fact, the word “capricious” derives from the old Italian caprizare, i.e. to move as a goat; this piece, therefore, is a quintessential “capriccio”.

Still another contrast is represented by a very famous work by Maurice Ravel, which exists in a variety of forms. His Pavane pour une infante défunte, written in 1899 for solo piano and orchestrated by the composer in 1910, had originally been conceived as a homage to the Princesse of Polignac. It is an evocation of the solemnity and gravity of courtly dances in Baroque Spain, seen through the lens of a double exoticism: geographic (Spain) and historic (Baroque). It is also an implicit homage to Gabriel Fauré, who was Ravel’s teacher at the time and who had written a very famous Pavane in turn.

Syrinx is one of the best-known works for unaccompanied flute in music history. Written in 1913 by Claude Debussy and dedicated to Louis Fleury, it had been conceived in turn as incidental music for Psyché by Gabriel Mourey, a friend of Debussy. Similar to the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, the work is centered on the figure of the dying Pan, whose beloved Syrinx was transformed into reeds and then into the eponymous musical instrument.

Penultimate… but not least (the last piece has been discussed already), Fauré’s Fantaisie is still another classic of the flute repertoire. Written on a commission by Paul Taffanel, it was conceived as an exam piece for the flute graduates of the Conservatoire. Even though it is designed to test the performer’s skills in terms of both technique and expressivity, it is by no means a “scholastic” work. It is a short masterpiece which has fully earned the fame and success it still enjoys.

Together, the works recorded here invite the listener to a journey made of dreams and “after-dreams”, of scraps of fantasy and consciousness which will certainly capture the audience.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads