Tracklist:

1. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 24: No. 1, Morgens steh’ ich auf und frage (01:09)

2. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 24: No. 2, Es treibt mich hin, es treibt mich her (01:25)

3. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 24: No. 3, Ich wandelte unter den Bäumen (03:58)

4. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 24: No. 4, Lieb’ Liebchen, leg’s Händchen auf’s Herze mein (00:54)

5. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 24: No. 5, Schöne Wiege meiner Leiden (04:05)

6. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 24: No. 6, Warte, warte, wilder Schiffmann (01:48)

7. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 24: No. 7, Berg’ und Burgen schau’n herunter (03:48)

8. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 24: No. 8, Anfangs wollt’ich fast verzagen (00:57)

9. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 24: No. 9, Mit Myrten und Rosen, lieblich und hold (04:10)

10. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 1, In der Fremde (02:10)

11. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 2, Intermezzo (02:02)

12. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 3, Waldesgespräch (02:16)

13. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 4, Die Stille (01:32)

14. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 5, Mondnacht (04:10)

15. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 6, Schöne Fremde (01:25)

16. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 7, Auf einer Burg (02:55)

17. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 8, In der Fremde (01:37)

18. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 9, Wehmut (02:43)

19. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 10, Zwielicht (03:12)

20. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 11, Im Walde (01:34)

21. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Liederkreis, Op. 39: No. 12, Frühlingsnacht (01:28)

22. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Mignon Lieder, Op. 98a: No. 1, Kennst du das Land? (04:32)

23. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Mignon Lieder, Op. 98a: No. 2, Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt (02:24)

24. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Mignon Lieder, Op. 98a: No. 3, Heiss’ mich nicht reden, heiss’ mich schweigen (03:43)

25. Joo Cho & Marino Nahon – Mignon Lieder, Op. 98a: No. 4, So lasst mich scheinen, bis ich werde (03:12)

Song has always been a landmark of human musicality and one of the foundational expressions of human artistry. True, one of the greatest theologians of music ever, i.e. St. Augustine, postulated that the highest form of singing was wordless singing, or what he called jubilus. He stated: “He who sings a jubilus does not utter words; he pronounces a wordless sound of joy; the voice of his soul pours forth happiness as intensely as possible, expressing what he feels without reflecting on any particular meaning; to manifest his joy, the man does not use words that can be pronounced and understood, but he simply lets his joy burst forth without words; his voice appears to express a happiness so intense that he cannot formulate it”. However, it is from the union, the tight union of words and music, that the greatest masterpieces of vocal music have been generated in music history.

This union, though, does not perforce require that both the author of the lyrics and the composer of the music be geniuses. Surely, there are cases of immense masterpieces coauthored by a genius author (e.g. Schiller) and a genius composer (Beethoven) – the result is the Ode to Joy. But, for instance, one of the absolute masterpieces of song literature, i.e. Franz Schubert’s Winterreise, is doubtlessly the work of a genius musician, whilst the same cannot be said of the poets signing the lyrics. What really matters, to make a masterful song, is that words and music match perfectly each other; and even though the lyrics may have some poetical shortcomings, if the corresponding music manages to silence these and to highlight their valuable aspects, the result can still be perfect.

While the importance of the word/music union applies to virtually all kinds of vocal music, it is crucial for the repertoire of (classical music) songs, or Lieder. There are, in fact, some operatic arias whose lyrics are far below any standard of acceptability in literary terms; to make just one example, Papageno’s aria Hm hm hm or his duet with Papagena, Pa-pa-pa cannot be counted among the finest examples of poetry. But both pieces are utterly enjoyable and really satisfactory to hear. Or there are other famous arias where the words (beautiful or awkward as they may be) are mere pretexts for the singer who shows off his or her virtuosity with wide-ranging cadenzas and embellishments.

In the world of Lieder, instead, such examples are virtually inexistent. A successful Lied is one whose lyrics and whose music are perfectly paired, perfectly combined, perfectly united and interwoven. Franz Schubert was doubtlessly the prime master of this union, in spite of the already-mentioned limitations of the poetry he at times employed. A different stance should be taken when considering the Lieder penned by Robert Schumann.

Schumann had been exceedingly attracted by literature since a very young age, to the point that he wavered for a long time between the literary and the musical career (or rather between these two vocations). Even though in the end he consecrated the best of his creative energies to music, this did not imply his renouncing or abandoning literature. He founded a journal, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, whose pages gave voice to his thoughts, musings, considerations and afterthoughts about music, art, society, and so forth. He wrote extensively, and also in the private or semi-private sphere he was able to shape the self-expression of his inner world with a level of refinement unreached by many self-describing authors.

His fantasy and his literary skills had been nourished by extensive, prolonged, and constant reading; indeed, even his musical creations are best understood only when they are put in dialogue with their literary sources of inspiration. If one name should be cited, it would be that of Jean Paul Richter (or Jean Paul, as Schumann called him): the stimuli provided to the young composer by his novels – in particular Flegeljahre – are punctually mapped in Papillons op. 2 and Carnaval op. 9. But, far beyond these (significant) examples, the influence of Jean Paul’s twin characters, Walt and Vult, on the creation of Schumann’s own “Florestan” and “Eusebius” (who were to remain his artistic personae and his lifelong alter egos) should not be underestimated.

Thus, Schumann was one who knew particularly well, and with an insider’s perspective, how the (German) language worked, its secrets, its sounds, its effects. He knew why a particular piece of poetry was a masterpiece; which were its pillars, its foundations, and which were its adornments and embellishments.

Furthermore, he had always been particularly at ease with small-scale composition, or, to be more precise, with the creation of masterworks made of tiny cells. Many of his great creations are piano cycles, at times of considerable length (such as Davidsbündlertänze, nearing a duration of 40 minutes), but made of short or very short pieces. One of the wonders realized by Schumann is that the result is by no means fragmentary, or patchwork: the listener is caught from the first to the last note, and it would be practically inconceivable to take one or more movements out of any of his cycles, or to perform one of these pieces alone. It is as if he made exquisite mosaics whose tiles are miniature paintings of their own.

In spite of this all – his literary talent, his literary knowledge, his gift and skill for miniatures and cycles of miniatures – Schumann did not write many Lieder before 1840, the year of his thirtieth birthday. True, he had composed some songs as a youth, but he had not been particularly satisfied with the result, possibly also due to the rendition of the dedicatee, who sang them but was probably not an excellent singer.

Then came the fateful year 1840, which is referred to by musicologists as the Liederjahr, the year of the Lieder, but which Schumann would probably remember as the wedding year. After having been in love with Clara Wieck for more than a decade, and having endlessly fought with her father, Friedrich Wieck, who was fiercely opposed to their relationship, Robert was now nearing the date when his fiancée and him would finally get married.

Thinking prosaically, writing Lieder was a very wise move for someone on the threshold of the wedding church. Schumann’s piano cycles were magnificent, but their publication did not certainly make him wealthy. They were too difficult for the plethora of amateur pianists who were rightly scared by their complexity. By way of contrast, songs (deceivingly) appeared as “easier” and more accessible.

Thus the impressive quantity of 150 Lieder saw the light in 1840. But, of course, the reason behind this flow was not merely financial or economic. Schumann found in the Lied the perfect form in which he could express his feelings of hope, pain, elation, grief, at that turning point of his life. The word employed by Schumann to refer to his op. 24 and op. 39 is Kreis, meaning “circle” rather than “cycle”. In the opinion of musicologist Wiora, this may mark a distinction between the cycle, where there is a narrative, an evolution in the story, and the circle, which has no such evolution but “merely” a unity of theme and subject.

Liederkreis op. 24 is set to lyrics by Heinrich Heine, selected from his Buch der Lieder (as would happen with Dichterliebe op. 48). The unity of this “circle” is highlighted by the many details interspersed by Schumann within its pages. There are melodic references and citations, which, in turn, mirror the highly symbolic and “dense” narrative texture of some of Schumann’s favourite literary works. Both the poetry and the music are full of references to auditory phenomena which become icons for states of mind and of the heart. The hyper-subjective depiction of the Romantic soul projects her feelings on the surrounding world, which, in turn, influences them. Nature and the self are seen as interacting with each other, and symbolizing each other. There is plenty of contrasting sentiments, feelings, passion and tenderness.

Another Liederkreis was finished a few months after op. 24; if the former dates from February 1840, the latter was written starting in May. In this case, the lyrics are excerpted from a collection by Joseph von Eichendorff, by the musically suggestive title of Intermezzo. Here too there is a background of natural evocations, which are transfigured in a dreamy fashion and painted in fascinating terms, and a close-up on the self and the soul, whose expression is at the heart of these Lieder. This “circle” of Lieder is masterfully conceived, also as concerns its tonal organization. It mirrors that of Chopin’s Preludes, and, moving by related keys, reaches a climax which then subsides. The tonal itinerary leads from F# minor to F# major, the key of the last song, which was and still is the best known of the collection.

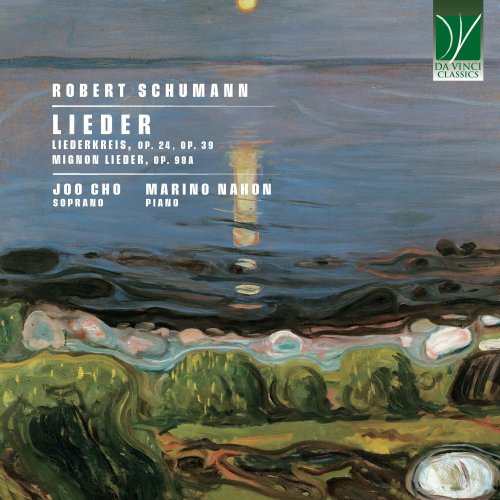

The last cycle recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album is that of the Mignon Lieder. They date from a later era, 1849, and it belongs in a long list of musical settings of Goethe’s poetry. In particular, the lyrics sung by the character of Mignon within Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister provided inspiration for a small army of composers, ranging from the greatest (Schubert, Schumann, Wolf, but also Tchaikovsky, whose Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt was one of the most beloved nineteenth-century songs) to amateurs. Schumann’s perspective on Mignon – who becomes an icon, a paradigm, a symbol for femininity – is different from Schubert’s; for him, Mignon is a young woman “on the threshold of adult life”. Schumann would also compose a Requiem for Mignon, op. 98b, which complements this series; the pathos and intensity of his musical renditions of Goethe’s poetry represent a perfect example of what can be created when sublime poetry – as Goethe’s – and sublime music – as Schumann’s – meet each other, and constitute a perfect unity of meaning, symbol, and beauty.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2024