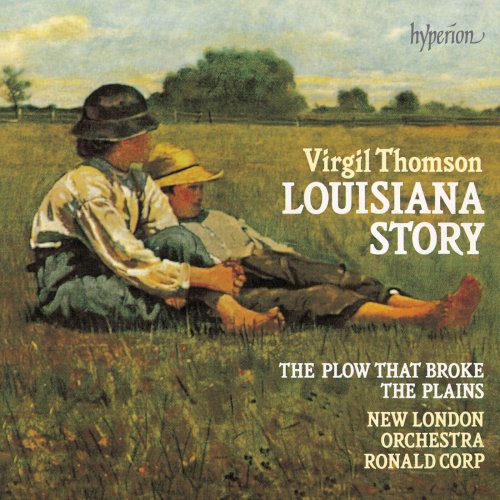

New London Orchestra, Ronald Corp - Virgil Thomson: Louisiana Story & Other Film Music (1992)

BAND/ARTIST: New London Orchestra, Ronald Corp

- Title: Virgil Thomson: Louisiana Story & Other Film Music

- Year Of Release: 1992

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:08:07

- Total Size: 222 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: I. Prelude. Prologue

02. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: II. Grass. Pastorale

03. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: III. Cattle

04. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: IV. Blues

05. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: V. Drought

06. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: VI. Devastation

07. Louisiana Story – Suite: I. Pastoral. The Bayou and the Marsh Buggy

08. Louisiana Story – Suite: II. Chorale. The Derrick Arrives

09. Louisiana Story – Suite: III. Passacaglia. Robbing the Alligator's Nest

10. Louisiana Story – Suite: IV. Fugue. Boy Fights Alligator

11. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: I. Sadness

12. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: II. Papa's Tune

13. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: III. A Narrative

14. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: IV. The Alligator and the 'Coon

15. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: V. Super-Sadness

16. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: VI. Walking Song

17. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: VII. The Squeeze Box

18. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: I. Prelude with Fugal Exposition

19. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: II. Fugue No. 1

20. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: III. Ruins and Jungles

21. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: IV. Fugue No. 2

22. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: V. Joyous Pastorale

23. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: VI. Finale

When we think of American films we think primarily of Hollywood, yet not one of the scores contained in this collection—the work of one of America’s most distinguished composers—was written for a Hollywood film. Thereby hangs a curious tale. Hollywood’s earliest sound-film composers rarely had the kind of academic or intellectual credentials that Thomson had (Harvard and Nadia Boulanger). The background of men like Steiner, Newman and Victor Young tended to be Broadway or Tin Pan Alley: their context was that of ‘commercial’ music of one sort or another. And ‘commercial’ music is generally conservative in style: Broadway musicals grew out of nineteenth-century operetta; pop songs and light music had to draw on a vocabulary that ordinary people could readily understand and relate to. So with early Hollywood film scores and their composers. Men like Copland and Thomson didn’t fit that mould. Nineteenth-century European romanticism held little attraction for them. They were more interested in the authentic musical past of their own country, in creating a music that was genuinely American, American in its essentials. Hollywood didn’t understand that sort of ‘American’ music, didn’t want it; and, of course, California was so geographically remote from other major American cultural centres that major cultural figures—the Thomsons, Coplands, Bernsteins—could never have worked there on a regular basis, even if they’d been invited. And Hollywood studios were never really happy with ‘moonlighters’: they didn’t fit into the system. The result was that Copland did a mere handful of Hollywood movies, Bernstein only one (On the Waterfront), and Thomson none at all. And there were dozens of other prominent, excellent, American composers who might have excelled in the film-score medium but who, the situation being what it was, never got the chance to try.

The films whose music is recorded here were produced independently of Hollywood; and, in the case of the first, The Plow that Broke the Plains, Hollywood was far from happy about it. Conductor Richard Kapp has explained how this and other films of its ilk originated in the attempts of Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ government to solve the crushing series of economic problems that beset America in the 1930s, the era of the Great Depression. Underlying the government’s unparalleled participation in subsidizing musicians, film-makers, graphic artists, writers, actors and others was a simple hypothesis. The nation was in the midst of unprecedented hard times and endemic unemployment. Surely the country stood to gain more by making use of its citizens’ talents—even if these appeared to have no value in the world of commerce—than it could by putting them on the dole and thus paying them not to work!

So it was that the Works Progress Administration, Farm Services Administration and other federal agencies and programmes assumed a responsibility for nurturing American composers, dramatists, writers and artists. One of them, the film-maker Pare Lorentz, in 1936 wrote and directed his first documentary for the Farm Services Administration. This was The Plow that Broke the Plains. (Lorentz had managed to persuade Roosevelt to create a US Government Film Service.) The film was made on a tiny budget, a venture without antecedents. It was intended as a documentation of the Dust Bowl, the agricultural disaster that had befallen the Plains States in the midst of times that were already hard. It was to serve as a propaganda vehicle for the administration: Washington was finally taking steps to remedy the disasters that had resulted from generations of greed and abuse of the land. Lorentz’s creative team was integrally involved at every stage. Thomson’s music evolved with the film; sometimes the film was edited to the music, sometimes the music to the film.

When it was first exhibited, The Plow created quite a sensation and achieved a degree of acceptance with the general film-going public that exceeded anything its film-makers, the Farm Services Administration or Hollywood could have envisaged. Its popular success had a number of consequences. One was the decision to make a second film, The River, which addressed itself to the Mississippi and the government’s efforts to redress the damage done by man. (Thomson scored this film also.) Another outcome that no one had predicted was an outcry from the commercial film community in Hollywood which saw Lorentz’s efforts as unfair government-inspired competition in the commercial marketplace. Hollywood increased its pressure until the Film Service was disbanded...

01. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: I. Prelude. Prologue

02. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: II. Grass. Pastorale

03. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: III. Cattle

04. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: IV. Blues

05. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: V. Drought

06. The Plow That Broke the Plains – Suite: VI. Devastation

07. Louisiana Story – Suite: I. Pastoral. The Bayou and the Marsh Buggy

08. Louisiana Story – Suite: II. Chorale. The Derrick Arrives

09. Louisiana Story – Suite: III. Passacaglia. Robbing the Alligator's Nest

10. Louisiana Story – Suite: IV. Fugue. Boy Fights Alligator

11. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: I. Sadness

12. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: II. Papa's Tune

13. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: III. A Narrative

14. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: IV. The Alligator and the 'Coon

15. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: V. Super-Sadness

16. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: VI. Walking Song

17. Louisiana Story – Acadian Songs and Dances: VII. The Squeeze Box

18. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: I. Prelude with Fugal Exposition

19. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: II. Fugue No. 1

20. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: III. Ruins and Jungles

21. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: IV. Fugue No. 2

22. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: V. Joyous Pastorale

23. Power Among Men – Fugues and Cantilenas: VI. Finale

When we think of American films we think primarily of Hollywood, yet not one of the scores contained in this collection—the work of one of America’s most distinguished composers—was written for a Hollywood film. Thereby hangs a curious tale. Hollywood’s earliest sound-film composers rarely had the kind of academic or intellectual credentials that Thomson had (Harvard and Nadia Boulanger). The background of men like Steiner, Newman and Victor Young tended to be Broadway or Tin Pan Alley: their context was that of ‘commercial’ music of one sort or another. And ‘commercial’ music is generally conservative in style: Broadway musicals grew out of nineteenth-century operetta; pop songs and light music had to draw on a vocabulary that ordinary people could readily understand and relate to. So with early Hollywood film scores and their composers. Men like Copland and Thomson didn’t fit that mould. Nineteenth-century European romanticism held little attraction for them. They were more interested in the authentic musical past of their own country, in creating a music that was genuinely American, American in its essentials. Hollywood didn’t understand that sort of ‘American’ music, didn’t want it; and, of course, California was so geographically remote from other major American cultural centres that major cultural figures—the Thomsons, Coplands, Bernsteins—could never have worked there on a regular basis, even if they’d been invited. And Hollywood studios were never really happy with ‘moonlighters’: they didn’t fit into the system. The result was that Copland did a mere handful of Hollywood movies, Bernstein only one (On the Waterfront), and Thomson none at all. And there were dozens of other prominent, excellent, American composers who might have excelled in the film-score medium but who, the situation being what it was, never got the chance to try.

The films whose music is recorded here were produced independently of Hollywood; and, in the case of the first, The Plow that Broke the Plains, Hollywood was far from happy about it. Conductor Richard Kapp has explained how this and other films of its ilk originated in the attempts of Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ government to solve the crushing series of economic problems that beset America in the 1930s, the era of the Great Depression. Underlying the government’s unparalleled participation in subsidizing musicians, film-makers, graphic artists, writers, actors and others was a simple hypothesis. The nation was in the midst of unprecedented hard times and endemic unemployment. Surely the country stood to gain more by making use of its citizens’ talents—even if these appeared to have no value in the world of commerce—than it could by putting them on the dole and thus paying them not to work!

So it was that the Works Progress Administration, Farm Services Administration and other federal agencies and programmes assumed a responsibility for nurturing American composers, dramatists, writers and artists. One of them, the film-maker Pare Lorentz, in 1936 wrote and directed his first documentary for the Farm Services Administration. This was The Plow that Broke the Plains. (Lorentz had managed to persuade Roosevelt to create a US Government Film Service.) The film was made on a tiny budget, a venture without antecedents. It was intended as a documentation of the Dust Bowl, the agricultural disaster that had befallen the Plains States in the midst of times that were already hard. It was to serve as a propaganda vehicle for the administration: Washington was finally taking steps to remedy the disasters that had resulted from generations of greed and abuse of the land. Lorentz’s creative team was integrally involved at every stage. Thomson’s music evolved with the film; sometimes the film was edited to the music, sometimes the music to the film.

When it was first exhibited, The Plow created quite a sensation and achieved a degree of acceptance with the general film-going public that exceeded anything its film-makers, the Farm Services Administration or Hollywood could have envisaged. Its popular success had a number of consequences. One was the decision to make a second film, The River, which addressed itself to the Mississippi and the government’s efforts to redress the damage done by man. (Thomson scored this film also.) Another outcome that no one had predicted was an outcry from the commercial film community in Hollywood which saw Lorentz’s efforts as unfair government-inspired competition in the commercial marketplace. Hollywood increased its pressure until the Film Service was disbanded...

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads