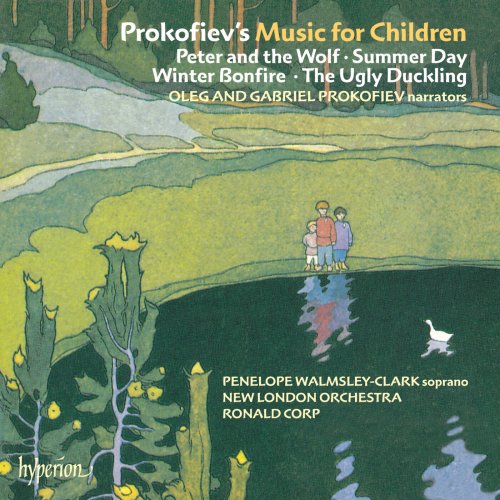

New London Orchestra, Ronald Corp - Prokofiev: Peter and the Wolf & Other Music for Children (1991)

BAND/ARTIST: New London Orchestra, Ronald Corp

- Title: Prokofiev: Peter and the Wolf & Other Music for Children

- Year Of Release: 1991

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:14:21

- Total Size: 257 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: I. Departure

02. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: II. Snow Outside the Window

03. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: III. Waltz on the Ice

04. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: IV. The Bonfire

05. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: V. Chorus of the Pioneers

06. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: VI. Winter Evening

07. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: VII. March

08. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: VIII. The Return

09. Summer Day, Op. 65a: I. Morning

10. Summer Day, Op. 65a: II. Tag (Tip and Run)

11. Summer Day, Op. 65a: III. Waltz

12. Summer Day, Op. 65a: IV. Repentance

13. Summer Day, Op. 65a: V. March

14. Summer Day, Op. 65a: VI. Evening

15. Summer Day, Op. 65a: VII. The Moon Sails over the Meadows

16. The Ugly Duckling, Op. 17

17. Peter and the Wolf, Op. 67 (Narration O. Prokofiev): I. We Would Like to Tell You the Story of Peter

18. Peter and the Wolf, Op. 67 (Narration O. Prokofiev): II. Early One Morning Peter Opened the Gate

Once we understand Prokofiev’s own child-like nature we need not be surprised that he took to writing children’s music like the duck (in his own Peter and the Wolf) took to jumping into – and, less sensibly, out of – the water. He had a truly child-like guilelessness of spirit: life for him was always a great adventure, with the unexpected lurking round every corner. Excitement was constantly in the air, everything was a cause for wonder, and when he declared that the composer’s business was ‘to serve his fellow men, to beautify human life and point the way to a radiant future’ (my italics) he wasn’t just rehearsing some mandatory Soviet ideological platitude but stating, simply and sincerely, his own artistic credo. No wonder his music has such vitality and colour. To the end he viewed the world as a child views it: hopefully and with joy in his heart. He had more than his fair share of misfortunes and disappointments – particularly after his return to Soviet Russia – but the light never went out. He believed, as children do, that all the best story books have Happy Endings.

Certainly Prokofiev’s own ‘stories’ for children end happily – and there are quite a number, not merely those recorded here. The first was The Ugly Duckling, a setting of an adaptation (by Nina Meshchersky, Prokofiev’s first ‘real’ girlfriend) of Hans Christian Andersen’s well-known fairy tale. The piece is not, however, designed specifically for children, who would probably be bewildered by the absence of ‘melodious’ melody. The text is in prose, not verse, and is set à la Mussorgsky as continuous melodic recitative: the form is that of a miniature operatic scena in which voice and orchestra set the drama to music as it unfolds, without formalizing it. The original voice and piano version was basic duckling, though hardly an ugly one! Prokofiev proceeded then to turn it into a large and beautiful orchestral swan in a way that relates interestingly to contemporaneous trends in Russian art: the bird and animal characterizations suggest the bright, sharp colours of Larionov, Goncharova and the Primitivists, whereas the nature-music – the deepening dark and cold of winter, the coming of spring and sunshine – is more akin to Impressionism (Borisov-Mussatov and Larionov’s early work).

Apart from the 1918 Tales of an Old Grandmother for piano (again, like the Duckling, not so much children’s music as music about children or the child’s world), Prokofiev did not return to this theme until the mid-1930s. By this time he was married with two children of his own and had decided to settle permanently in Soviet Russia – where, of course, policies of coercion-through-indoctrination were particularly aimed at children, and composers were urged to compose for ‘the people’ in general and ‘young’ people in particular. Hence the twelve short and simple piano pieces of Opus 65, Music for Children, simple enough for children to play, written in 1935 at the same time as the ballet Romeo and Juliet. In 1941 the composer selected seven of the twelve and scored them for small orchestra, sacrificing some of their transparency in the process but giving them a new dimension of colour and also, of course, bringing them a wider audience. He awarded the ‘new’ work a new title, Summer Day. Two of the most attractive pieces, ‘Waltz’ and ‘Evening’, turned up later in yet another context, the ballet The Stone Flower (1948–50). The origin of the last movement, ‘The moon sails over the meadows’, was described by Prokofiev in an autobiographical sketch: ‘I was staying in Polenovo at the time in a little cottage with a balcony overlooking the Oka, and in the evenings I often watched the moon floating over the fields and meadows.’

1936 was the year of Peter and the Wolf (of which much more anon); 1936–9 yielded the delightful Three Children’s Songs; out of the misery of the war years came the fairy tale ballet Cinderella, all dazzling and glittering in its finery; then in 1949–50, even though by then Prokofiev was mortally sick, he produced two substantial works, the children’s suite Winter Bonfire and the oratorio On Guard for Peace. Both involved a children’s choir singing words by the Soviet children’s poet Samuil Marshak, and both were first performed in Moscow on the same evening (19 December 1950) with Prokofiev’s indefatigable champion Samuil Samosud conducting. Winter Bonfire is a day in the life of some ‘young pioneers’ and describes an expedition to the country in winter. Peter might have been among them – his basic key of C major is theirs too – but whereas Peter’s music had more than a touch of Euro-Classical sophistication, Winter Bonfire is Russian through and through and of egregious pedigree (Tchaikovsky and Mussorgsky, both renowned for the authenticity of their children’s music). Prokofiev’s train-music (‘Departure’ and ‘The Return’), his whirlingly vigorous ice-skater’s waltz and the march which leads straight into ‘The Return’ are among his most winning inspirations, as is his use of tremolando strings in ‘The Bonfire’ to depict the shimmer and glow of the fire.

The children’s choir which sings in ‘Chorus of the pioneers’ foreshadows the more extensive use of children’s voices (solo and en masse) in On Guard for Peace, in the gala-finale of which they metaphorically release large flocks of (emblematic) doves into the summer sky over Moscow...

01. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: I. Departure

02. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: II. Snow Outside the Window

03. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: III. Waltz on the Ice

04. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: IV. The Bonfire

05. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: V. Chorus of the Pioneers

06. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: VI. Winter Evening

07. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: VII. March

08. Winter Bonfire, Op. 122: VIII. The Return

09. Summer Day, Op. 65a: I. Morning

10. Summer Day, Op. 65a: II. Tag (Tip and Run)

11. Summer Day, Op. 65a: III. Waltz

12. Summer Day, Op. 65a: IV. Repentance

13. Summer Day, Op. 65a: V. March

14. Summer Day, Op. 65a: VI. Evening

15. Summer Day, Op. 65a: VII. The Moon Sails over the Meadows

16. The Ugly Duckling, Op. 17

17. Peter and the Wolf, Op. 67 (Narration O. Prokofiev): I. We Would Like to Tell You the Story of Peter

18. Peter and the Wolf, Op. 67 (Narration O. Prokofiev): II. Early One Morning Peter Opened the Gate

Once we understand Prokofiev’s own child-like nature we need not be surprised that he took to writing children’s music like the duck (in his own Peter and the Wolf) took to jumping into – and, less sensibly, out of – the water. He had a truly child-like guilelessness of spirit: life for him was always a great adventure, with the unexpected lurking round every corner. Excitement was constantly in the air, everything was a cause for wonder, and when he declared that the composer’s business was ‘to serve his fellow men, to beautify human life and point the way to a radiant future’ (my italics) he wasn’t just rehearsing some mandatory Soviet ideological platitude but stating, simply and sincerely, his own artistic credo. No wonder his music has such vitality and colour. To the end he viewed the world as a child views it: hopefully and with joy in his heart. He had more than his fair share of misfortunes and disappointments – particularly after his return to Soviet Russia – but the light never went out. He believed, as children do, that all the best story books have Happy Endings.

Certainly Prokofiev’s own ‘stories’ for children end happily – and there are quite a number, not merely those recorded here. The first was The Ugly Duckling, a setting of an adaptation (by Nina Meshchersky, Prokofiev’s first ‘real’ girlfriend) of Hans Christian Andersen’s well-known fairy tale. The piece is not, however, designed specifically for children, who would probably be bewildered by the absence of ‘melodious’ melody. The text is in prose, not verse, and is set à la Mussorgsky as continuous melodic recitative: the form is that of a miniature operatic scena in which voice and orchestra set the drama to music as it unfolds, without formalizing it. The original voice and piano version was basic duckling, though hardly an ugly one! Prokofiev proceeded then to turn it into a large and beautiful orchestral swan in a way that relates interestingly to contemporaneous trends in Russian art: the bird and animal characterizations suggest the bright, sharp colours of Larionov, Goncharova and the Primitivists, whereas the nature-music – the deepening dark and cold of winter, the coming of spring and sunshine – is more akin to Impressionism (Borisov-Mussatov and Larionov’s early work).

Apart from the 1918 Tales of an Old Grandmother for piano (again, like the Duckling, not so much children’s music as music about children or the child’s world), Prokofiev did not return to this theme until the mid-1930s. By this time he was married with two children of his own and had decided to settle permanently in Soviet Russia – where, of course, policies of coercion-through-indoctrination were particularly aimed at children, and composers were urged to compose for ‘the people’ in general and ‘young’ people in particular. Hence the twelve short and simple piano pieces of Opus 65, Music for Children, simple enough for children to play, written in 1935 at the same time as the ballet Romeo and Juliet. In 1941 the composer selected seven of the twelve and scored them for small orchestra, sacrificing some of their transparency in the process but giving them a new dimension of colour and also, of course, bringing them a wider audience. He awarded the ‘new’ work a new title, Summer Day. Two of the most attractive pieces, ‘Waltz’ and ‘Evening’, turned up later in yet another context, the ballet The Stone Flower (1948–50). The origin of the last movement, ‘The moon sails over the meadows’, was described by Prokofiev in an autobiographical sketch: ‘I was staying in Polenovo at the time in a little cottage with a balcony overlooking the Oka, and in the evenings I often watched the moon floating over the fields and meadows.’

1936 was the year of Peter and the Wolf (of which much more anon); 1936–9 yielded the delightful Three Children’s Songs; out of the misery of the war years came the fairy tale ballet Cinderella, all dazzling and glittering in its finery; then in 1949–50, even though by then Prokofiev was mortally sick, he produced two substantial works, the children’s suite Winter Bonfire and the oratorio On Guard for Peace. Both involved a children’s choir singing words by the Soviet children’s poet Samuil Marshak, and both were first performed in Moscow on the same evening (19 December 1950) with Prokofiev’s indefatigable champion Samuil Samosud conducting. Winter Bonfire is a day in the life of some ‘young pioneers’ and describes an expedition to the country in winter. Peter might have been among them – his basic key of C major is theirs too – but whereas Peter’s music had more than a touch of Euro-Classical sophistication, Winter Bonfire is Russian through and through and of egregious pedigree (Tchaikovsky and Mussorgsky, both renowned for the authenticity of their children’s music). Prokofiev’s train-music (‘Departure’ and ‘The Return’), his whirlingly vigorous ice-skater’s waltz and the march which leads straight into ‘The Return’ are among his most winning inspirations, as is his use of tremolando strings in ‘The Bonfire’ to depict the shimmer and glow of the fire.

The children’s choir which sings in ‘Chorus of the pioneers’ foreshadows the more extensive use of children’s voices (solo and en masse) in On Guard for Peace, in the gala-finale of which they metaphorically release large flocks of (emblematic) doves into the summer sky over Moscow...

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads