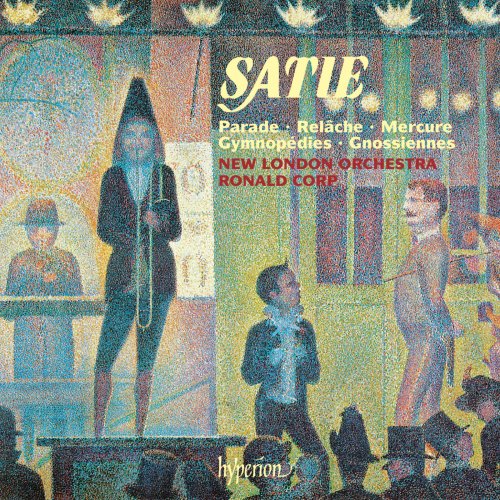

New London Orchestra, Ronald Corp - Satie: Parade, Gymnopédies, Gnossiennes & Other Works for Orchestra (1989)

BAND/ARTIST: New London Orchestra, Ronald Corp

- Title: Satie: Parade, Gymnopédies, Gnossiennes & Other Works for Orchestra

- Year Of Release: 1989

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:06:04

- Total Size: 228 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Parade: I. Choral

02. Parade: II. Prélude du rideau rouge

03. Parade: III. Prestidigitateur chinois

04. Parade: IV. Petite fille américaine

05. Parade: V. Acrobates

06. Parade: VI. Final

07. Parade: VII. Suite au «Prélude du rideau rouge»

08. Gymnopédie No. 1 (Orch. Debussy)

09. Gymnopédie No. 2 (Orch. Corp)

10. Gymnopédie No. 3 (Orch. Debussy)

11. Mercure: I. Ouverture

12. Mercure: II. La nuit

13. Mercure: III. Danse de tendresse

14. Mercure: IV. Signes du Zodiaque

15. Mercure: V. Entrée et danse de Mercure

16. Mercure: VI. Danse des Grâces

17. Mercure: VII. Bain des Grâces

18. Mercure: VIII. Fuite de Mercure

19. Mercure: IX. Colère de Cerbère

20. Mercure: X. Polka des lettres

21. Mercure: XI. Nouvelle danse

22. Mercure: XII. Le Chaos

23. Mercure: XIII. Finale

24. Gnossienne No. 1 (Orch. Corp)

25. Gnossienne No. 2 (Orch. Corp)

26. Gnossienne No. 3 (Orch. Corp)

27. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 1, Ouverturette

28. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 2, Projectionnette

29. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 3, Entrée de la femme

30. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 4, Musique

31. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 5, Entrée de Borlin

32. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 6, Danse de la porte tournante

33. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 7, Entrée des hommes

34. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 8, Danse des hommes

35. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 9, Danse de la femme

36. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 10, Final

37. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 1, Musique de rentrée

38. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 2, Rentrée des hommes

39. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 3, Rentrée de la femme

40. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 4, Les hommes se dévêtissent

41. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 5, Danse de Borlin et de la femme

42. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 6, Les hommes

43. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 7, Danse de la brouette

44. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 8, Danse de la couronne

45. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 9, Le danseur repose la couronne sur la tête d"une spectatrice

46. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 10, La femme rejoint son fauteuil

47. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 11, La queue du chien (chanson mimée)

’English critics have been unanimous in their disapproval, and one has yet to see that their contempt is based on any knowledge of his works as a whole.’ Thus wrote the composer Constant Lambert in his 1934 searing, witty ‘study of music in decline’ Music Ho! of the recently deceased Erik Satie. And this is the view generally held of Satie at that time, and for several decades thereafter – he was a prankster, an eccentric, a café pianist and musical charlatan with little to say beyond nothing, a confectioner of trifles and peculiar titles, and a recluse who deserved to remain so. The championship of Satie’s music by the avant-garde of the 1950s and 1960s and the publication of much biographical information, and also of a collection of his own writings, have done much to redress the balance, and today he is seen in his correct historical position as something of a visionary, a composer who, as the ever-perceptive Lambert wrote, ‘had the no doubt gratifying sensation of seeing the times catch up with him’, and who was godfather of the musical movement that truly liberated music from its romantic, chromatic morass.

The harmonically clear and very French aesthetic of Satie is nowhere better seen than in his Trois Gymnopédies for piano, which were among his earliest published compositions. They have proved his most popular works, not only because of his friend Debussy’s orchestrations of two of them, but also through their haunting simplicity and classical restraint. Again we can paraphrase Lambert, who likened the aural effect of these three rather similar pieces to walking around a piece of sculpture, viewing it from various angles. Satie preferred not really to explain the rather esoteric title: it has always been assumed that the word ‘gymnopédies’ vaguely refers to the dances performed for several days without interruption by naked youths in classical Sparta. Debussy decided to orchestrate two of the three Gymnopédies after hearing Satie play them (not particularly well) on the piano at the house of the conductor Gustave Doret in 1896. They were first performed at a Société Nationale concert on 20 February 1897. Debussy orchestrated Satie’s first and third Gymnopédies and reversed this order upon publication. There have been many orchestrations of the Gymnopédie missed by Debussy (No 2); that recorded here is by Ronald Corp, who uses the same orchestra as Debussy and very much continues the mood of unity and calm established by him.

Ronald Corp retains Debussy’s chamber orchestra (two flutes, oboe, four horns, harp, and strings) for his scoring of the Trois Gnossiennes, a similarly mysterious set of pieces written for piano by Satie in 1890. These miniatures, originally notated without bar lines or time signatures, again evoke a half-remembered and certainly long-vanished antiquity. Does the title refer to the stately Cretan figures endlessly circling the dark pottery of Knossos? We do not know, and it matters not. Satie’s semi-humorous but deadpan performing indications («Munissez-vous de clairvoyance», «Ouvrez la tête», and «Seul, pendant un instant», for example) are, doubtless, further red herrings, and side-swipes at the increasingly elaborate instructions with which Debussy was beginning to litter his own scores. The repetitive, motivic nature of his modally based melodies in Gnossiennes, with their parallel chordal accompaniments, also shows Satie’s developing interest in religious chant and monody, an interest that became an obsession.

The dazzling French writer Jean Cocteau (1891–1963) left a charming thumb-nail sketch of Satie which is worth quoting in the context of the collaboration between the two men, together with Pablo Picasso and Léonide Massine, on the so-called ‘ballet réaliste’ Parade (1915–16) which Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes presented in Paris on 18 May 1917, and which not exactly modestly echoed the ripples of scandal caused by the same company’s Rite of Spring furore some years earlier. ‘For several years Erik Satie would come during the morning to No 10 rue d’Anjou and sit in my room’, wrote Cocteau; ‘he would keep on his overcoat (he could not have tolerated the slightest mark on it), his gloves, his hat, tilted right down over the eye-glass, and hold his umbrella in his hand. With his other hand he would cover his mouth, which curled when he talked or laughed. He used to come from Arcueil on foot. He lived there in a small room where, after his death, all the letters from his friends were found under a huge heap of dust. He had not opened one of them … (He would) tease Ravel, and out of modesty give to the fine pieces of music played by Ricardo Viñes comical titles calculated to alienate immediately a host of mediocre minds.’

It was not only mediocre minds that were alienated by the cock-snooking, surrealist world of Parade, peopled as it was on that May night in 1917 by a Chinese conjuror, cops and robbers, acrobats, circus folk of all descriptions, and three seriously down-to-earth and very ‘Cubist’ managers. The performance was drowned in the audience uproar, and the resulting journalistic battle resulted in a court case and a prison sentence for Satie which, typically, he managed never to serve. The fact that Parade saw the unique meeting of the greatest artistic minds offered by Paris at that time was conveniently overlooked.

Picasso’s cubist and colourful costumes, curtains, and scenery for Parade, with Massine’s choreography to match, were directly reflected in Satie’s ‘cubist’ score, which unfolds in a clockwork, mechanical and rather dry though exceedingly amusing way. Typewriters, revolvers, sirens, and clappers all find their place in the mêlée, the madness, and the melancholy of Parade. And, as the circus that departs overnight, it is all too soon gone, like the Midsummer Night’s Dream, an adaptation of which Cocteau was working on when he first met Satie in 1915.

Cocteau was Satie’s muse again in his next ballet, Les aventures de Mercure (1924), and once more Picasso and Massine played their respective parts. Mercure was written for the famous ‘Soirées de Paris’ organized by Étienne de Beaumont, and first given on 15 June 1924 at the Théâtre de la Cigale. The score is subtitled ‘three dimensional poses in three images’, and the ballet presents a dazzling array of classical figures engaged in various ‘poses’, and revealing unexpected aspects of themselves. We are walking around sculptures again as we hear in quick succession ‘Dance of the Graces’, ‘Flight of Mercury’, and ‘Anger of Cerberus’, amongst others, depicted in brassy, coarse, and café-concertish tones, beneath which always lurks a hint of loving tenderness.

And so to Satie’s last months of life, and his final ballet, Relâche. ‘Relâche’ is the word used in France to indicate that a theatre has closed or a performance is cancelled. The first performance was indeed ‘cancelled’; the audience arrived on the prescribed night to find the theatre in darkness. The real premiere took place three nights later on 30 November 1924. With a nonsense scenario by Francis Picabia, and the showing of an absurd film by René Clair during the interval (with music by Satie, one of the earliest and most perceptive of film scores – again, the times catching up with him), the score seemed to Satie’s detractors to be his greatest débâcle to date. Virtually plotless, and with a backdrop of enormous gramophone records, how could Satie be taken seriously? Perhaps we should content ourselves with Satie’s own summary of Relâche (and hence his own life) and have done with: ‘I want to compose a piece for dogs, and I already have my decor. The curtain rises on a bone.’ The ballet’s inclusion of a coffin and a hearse was morbidly prophetic: Satie died as he had lived, a humble but egocentric recluse, just seven months later.

01. Parade: I. Choral

02. Parade: II. Prélude du rideau rouge

03. Parade: III. Prestidigitateur chinois

04. Parade: IV. Petite fille américaine

05. Parade: V. Acrobates

06. Parade: VI. Final

07. Parade: VII. Suite au «Prélude du rideau rouge»

08. Gymnopédie No. 1 (Orch. Debussy)

09. Gymnopédie No. 2 (Orch. Corp)

10. Gymnopédie No. 3 (Orch. Debussy)

11. Mercure: I. Ouverture

12. Mercure: II. La nuit

13. Mercure: III. Danse de tendresse

14. Mercure: IV. Signes du Zodiaque

15. Mercure: V. Entrée et danse de Mercure

16. Mercure: VI. Danse des Grâces

17. Mercure: VII. Bain des Grâces

18. Mercure: VIII. Fuite de Mercure

19. Mercure: IX. Colère de Cerbère

20. Mercure: X. Polka des lettres

21. Mercure: XI. Nouvelle danse

22. Mercure: XII. Le Chaos

23. Mercure: XIII. Finale

24. Gnossienne No. 1 (Orch. Corp)

25. Gnossienne No. 2 (Orch. Corp)

26. Gnossienne No. 3 (Orch. Corp)

27. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 1, Ouverturette

28. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 2, Projectionnette

29. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 3, Entrée de la femme

30. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 4, Musique

31. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 5, Entrée de Borlin

32. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 6, Danse de la porte tournante

33. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 7, Entrée des hommes

34. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 8, Danse des hommes

35. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 9, Danse de la femme

36. Relâche, Pt. 1: No. 10, Final

37. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 1, Musique de rentrée

38. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 2, Rentrée des hommes

39. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 3, Rentrée de la femme

40. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 4, Les hommes se dévêtissent

41. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 5, Danse de Borlin et de la femme

42. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 6, Les hommes

43. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 7, Danse de la brouette

44. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 8, Danse de la couronne

45. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 9, Le danseur repose la couronne sur la tête d"une spectatrice

46. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 10, La femme rejoint son fauteuil

47. Relâche, Pt. 2: No. 11, La queue du chien (chanson mimée)

’English critics have been unanimous in their disapproval, and one has yet to see that their contempt is based on any knowledge of his works as a whole.’ Thus wrote the composer Constant Lambert in his 1934 searing, witty ‘study of music in decline’ Music Ho! of the recently deceased Erik Satie. And this is the view generally held of Satie at that time, and for several decades thereafter – he was a prankster, an eccentric, a café pianist and musical charlatan with little to say beyond nothing, a confectioner of trifles and peculiar titles, and a recluse who deserved to remain so. The championship of Satie’s music by the avant-garde of the 1950s and 1960s and the publication of much biographical information, and also of a collection of his own writings, have done much to redress the balance, and today he is seen in his correct historical position as something of a visionary, a composer who, as the ever-perceptive Lambert wrote, ‘had the no doubt gratifying sensation of seeing the times catch up with him’, and who was godfather of the musical movement that truly liberated music from its romantic, chromatic morass.

The harmonically clear and very French aesthetic of Satie is nowhere better seen than in his Trois Gymnopédies for piano, which were among his earliest published compositions. They have proved his most popular works, not only because of his friend Debussy’s orchestrations of two of them, but also through their haunting simplicity and classical restraint. Again we can paraphrase Lambert, who likened the aural effect of these three rather similar pieces to walking around a piece of sculpture, viewing it from various angles. Satie preferred not really to explain the rather esoteric title: it has always been assumed that the word ‘gymnopédies’ vaguely refers to the dances performed for several days without interruption by naked youths in classical Sparta. Debussy decided to orchestrate two of the three Gymnopédies after hearing Satie play them (not particularly well) on the piano at the house of the conductor Gustave Doret in 1896. They were first performed at a Société Nationale concert on 20 February 1897. Debussy orchestrated Satie’s first and third Gymnopédies and reversed this order upon publication. There have been many orchestrations of the Gymnopédie missed by Debussy (No 2); that recorded here is by Ronald Corp, who uses the same orchestra as Debussy and very much continues the mood of unity and calm established by him.

Ronald Corp retains Debussy’s chamber orchestra (two flutes, oboe, four horns, harp, and strings) for his scoring of the Trois Gnossiennes, a similarly mysterious set of pieces written for piano by Satie in 1890. These miniatures, originally notated without bar lines or time signatures, again evoke a half-remembered and certainly long-vanished antiquity. Does the title refer to the stately Cretan figures endlessly circling the dark pottery of Knossos? We do not know, and it matters not. Satie’s semi-humorous but deadpan performing indications («Munissez-vous de clairvoyance», «Ouvrez la tête», and «Seul, pendant un instant», for example) are, doubtless, further red herrings, and side-swipes at the increasingly elaborate instructions with which Debussy was beginning to litter his own scores. The repetitive, motivic nature of his modally based melodies in Gnossiennes, with their parallel chordal accompaniments, also shows Satie’s developing interest in religious chant and monody, an interest that became an obsession.

The dazzling French writer Jean Cocteau (1891–1963) left a charming thumb-nail sketch of Satie which is worth quoting in the context of the collaboration between the two men, together with Pablo Picasso and Léonide Massine, on the so-called ‘ballet réaliste’ Parade (1915–16) which Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes presented in Paris on 18 May 1917, and which not exactly modestly echoed the ripples of scandal caused by the same company’s Rite of Spring furore some years earlier. ‘For several years Erik Satie would come during the morning to No 10 rue d’Anjou and sit in my room’, wrote Cocteau; ‘he would keep on his overcoat (he could not have tolerated the slightest mark on it), his gloves, his hat, tilted right down over the eye-glass, and hold his umbrella in his hand. With his other hand he would cover his mouth, which curled when he talked or laughed. He used to come from Arcueil on foot. He lived there in a small room where, after his death, all the letters from his friends were found under a huge heap of dust. He had not opened one of them … (He would) tease Ravel, and out of modesty give to the fine pieces of music played by Ricardo Viñes comical titles calculated to alienate immediately a host of mediocre minds.’

It was not only mediocre minds that were alienated by the cock-snooking, surrealist world of Parade, peopled as it was on that May night in 1917 by a Chinese conjuror, cops and robbers, acrobats, circus folk of all descriptions, and three seriously down-to-earth and very ‘Cubist’ managers. The performance was drowned in the audience uproar, and the resulting journalistic battle resulted in a court case and a prison sentence for Satie which, typically, he managed never to serve. The fact that Parade saw the unique meeting of the greatest artistic minds offered by Paris at that time was conveniently overlooked.

Picasso’s cubist and colourful costumes, curtains, and scenery for Parade, with Massine’s choreography to match, were directly reflected in Satie’s ‘cubist’ score, which unfolds in a clockwork, mechanical and rather dry though exceedingly amusing way. Typewriters, revolvers, sirens, and clappers all find their place in the mêlée, the madness, and the melancholy of Parade. And, as the circus that departs overnight, it is all too soon gone, like the Midsummer Night’s Dream, an adaptation of which Cocteau was working on when he first met Satie in 1915.

Cocteau was Satie’s muse again in his next ballet, Les aventures de Mercure (1924), and once more Picasso and Massine played their respective parts. Mercure was written for the famous ‘Soirées de Paris’ organized by Étienne de Beaumont, and first given on 15 June 1924 at the Théâtre de la Cigale. The score is subtitled ‘three dimensional poses in three images’, and the ballet presents a dazzling array of classical figures engaged in various ‘poses’, and revealing unexpected aspects of themselves. We are walking around sculptures again as we hear in quick succession ‘Dance of the Graces’, ‘Flight of Mercury’, and ‘Anger of Cerberus’, amongst others, depicted in brassy, coarse, and café-concertish tones, beneath which always lurks a hint of loving tenderness.

And so to Satie’s last months of life, and his final ballet, Relâche. ‘Relâche’ is the word used in France to indicate that a theatre has closed or a performance is cancelled. The first performance was indeed ‘cancelled’; the audience arrived on the prescribed night to find the theatre in darkness. The real premiere took place three nights later on 30 November 1924. With a nonsense scenario by Francis Picabia, and the showing of an absurd film by René Clair during the interval (with music by Satie, one of the earliest and most perceptive of film scores – again, the times catching up with him), the score seemed to Satie’s detractors to be his greatest débâcle to date. Virtually plotless, and with a backdrop of enormous gramophone records, how could Satie be taken seriously? Perhaps we should content ourselves with Satie’s own summary of Relâche (and hence his own life) and have done with: ‘I want to compose a piece for dogs, and I already have my decor. The curtain rises on a bone.’ The ballet’s inclusion of a coffin and a hearse was morbidly prophetic: Satie died as he had lived, a humble but egocentric recluse, just seven months later.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads