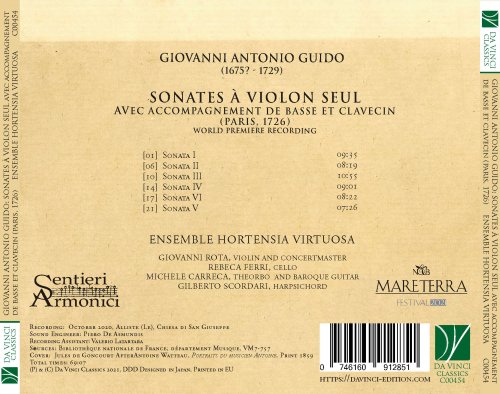

Giovanni Rota, Ensemble Hortensia Virtuosa - Giovanni Antonio Guido: Sonates à violon seul avec accompagnement de basse et clavecin (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Giovanni Rota, Ensemble Hortensia Virtuosa

- Title: Giovanni Antonio Guido: Sonates à violon seul avec accompagnement de basse et clavecin

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 00:53:41

- Total Size: 337 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Sonata I: I. Adagio-Un poco Andante

02. Sonata I: II. Vivace

03. Sonata I: III. Adagio

04. Sonata I: IV. Allegro e non presto

05. Sonata I: V. Gavotta

06. Sonata II: I. Adagio

07. Sonata II: II. Allegro e non presto

08. Sonata II: III. Gratioso

09. Sonata II: IV. Allegro

10. Sonata III: I. Preludio Adagio. Un poco Andante

11. Sonata III: II. Allegro

12. Sonata III: III. Piacevole

13. Sonata III: IV. Allegro

14. Sonata IV: I. Adagio

15. Sonata IV: II. Allegro

16. Sonata IV: III. Adagio. Allegro. Adagio

17. Sonata IV: IV. Allegro

18. Sonata, vol. I: I. Adagio

19. Sonata, vol. I: II. Allegro

20. Sonata, vol. I: III. Sarabanda

21. Sonata, vol. I: IV. Gavotta

22. Sonata V: I. Adagio

23. Sonata V: II. Allegro e Spiccato

24. Sonata V: III. Adagio

25. Sonata V: IV. La caccia. Allegro

The reception of new Italian music in France at the beginning of the 18th century gained an extraordinary momentum in connection with profound social and political developments. The arrival of new music and, above all, of talented virtuosi from Italy stimulated an intense debate over the respective aesthetic value of the Italian and French musical traditions in which Italian music was seen as the aural representation of a new society that aspired to take distance from the court of Louis XIV.

Several Italian musicians who arrived in Paris at the beginning of the 18th century found in the new cultural climate of the French capital the perfect conditions for their successful careers. They participated to the rich artistic exchanges between the two nations and contributed to the spread of the Italian violin sonata in France. The fact that many of these virtuosi active in Paris were coming from Naples, although often unnoticed by modern historiographical narratives, was not a coincidence: it was the consequence of the advancement of the Neapolitan string tradition, but it also derived from the new political liaisons between Naples and Paris. Between 1702 and 1707 the Kingdom of Naples came temporarily under the control of the French monarchy; the new dominion favored the contacts between the two capitals and opened up career opportunities to Neapolitan musicians.

Giovanni Antonio Guido (ca. 1675- after 1733) was probably the first Neapolitan musician to move to Paris, where he achieved a high reputation both as a performer and composer. As the tile page of his collection of Mottetti (1707) attests and documents about his admission at the conservatory confirm, Guido was born in Genoa around 1675. He then moved to Naples where he studied violin at the Conservatory of S. Maria della Pietà dei Turchini. After completing his studies in 1690, Guido entered the prestigious ensemble of the Royal Chapel; his name appears in the official list of personnel as a regular member of the chapel from September 1698 through December 1701. In January 1702 a dispatch from the Cappellano Maggiore announced his replacement. It is therefore around that time that we can date Guido’s move to Paris.

In the French capital the Neapolitan violinist rapidly became one of the protagonists of the profound changes that impacted French artistic life and influenced the development of music aesthetics and criticism. The first mention of his activity in Paris is in connection with the patronage of Italian artists by the duke Philippe d’Orléans. The complex personality and powerful position of Philippe d’Orléans made him the leader of the Italianate party in the French capital. In a time when the confrontation over musical taste had political overtones, Philippe’s patronage of Giovanni Antonio Guido and of other Italian musicians became the expression of his opposition to the stifling politics of Louis XIV’s regime and projected his crucial role in the renovation of French high society.

The future Regent of France put together an Italian ensemble unique in France, formed by two singers and two violinists of Italian training and various other French musicians hired on the occasion. It was with this ensemble that Guido made his debut in France. In November 1703 the visit of the Queen of England at Fontainebleau included a concert with the participation of the two castrati, Pasqualino Tiepoli and Pasqualino Betti — whom the Duc d’Orléans had borrowed from Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni — Guido and Baptiste Anet playing violin and Joseph Marchand, “Basse de violon.”

Without doubt the protection of this powerful patron gave Guido the opportunity for rapidly advancing his career. Again, in September 1704 the Mercure Galant gave notice of a concert at the residence of the duchesse du Maine at Sceaux during which Guido had one of his vocal pieces performed before Louis XIV. In less than two years after his departure from Naples, Guido – now usually mentioned with the appellative of Antonio – was therefore at the center of the Parisian musical world both as a performer and composer. That his name was well known to the public of Paris is evident from his inclusion among the “virtuosi de l’Italie” in the second part of Lecerf de la Viéville’s Comparaison de la musique italienne e de la musique françoise, which appeared in 1705. A further testimony to the fame he enjoyed came in the annotations added to the English translation of François Raguenet’s Parallèle des Italiens et des Français en ce qui regarde la musique e les opéras in 1709 — later included by John Hawkins in his A General History of the Science and Practice of Music — in which Guido was listed among the most prominent musicians of the time.

With the beginning of Philippe d’Orléans’ regency in 1715 and the transfer of the court to the Palais Royal, the heart of the political, economic, and administrative life of France moved from Versailles to Paris. An emerging aristocracy of wealth embraced new artistic expressions, becoming an enthusiastic promoter of cultural events, and the practice of organizing public entertainments began to spread. Pierre Crozat (1661-1740), belonged to one of the wealthiest families in France – his father was a banker in Toulouse, and his brother, Antoine, “the wealthiest man in Paris,” had received from the king the exclusive trading and governing rights to the territories of Louisiana. Between 1715 and 1725 Pierre held regular concerts at his splendid residence in rue Richelieu, events that attracted a public of intellectuals, nobles, and music amateurs, as well as professional artists and musicians. The atmosphere of those gatherings survives in several drawings made by the famous painter Antoine Watteau. Indeed, Giovanni Antonio Guido’s participation in these soirees is confirmed by a small portrait of the musician realized by Watteau, probably around 1720. In the 1720s and 1730s Guido’s music was also performed at the Concert Spirituel and at other important concert venues in the French capital.

The collection that Giovanni Antonio Guido published in 1726 – dedicated to Louis d’Orléans, the son of the late Regent – marks a shift toward the assimilation of the French and Italian style in the so-called goûts réunis (“reunited tastes”).

The choice of solo violin sonatas already reveals the composer’s intention to adopt the most progressive language. While several of the slow movements recall the Corellian style – the elegant opening movement of the fifth sonata offers even an example of a quasi-Handelian ‘classicism’ – the adoption of tempo indications such as Piacevole or Gratioso, show a tendency toward a more marked galant style, possibly mediated by the influence of other Italian successful composers active in Paris at the time, such as Michele Mascitti.

Without completely abandoning the characteristics of his previous writing, Guido introduces in these sonatas traits of the French style: a more flowing melodic line is given to the violin, while the bass often accompanies it with simpler harmonies and clear-cut phrases, but sometimes intervening in an active dialogue with the violin, as in the Allegro e non Presto of the second sonata. The French elements emerge in several sonatas of the collection, for instance in the inclusion of dances such as the gavottas that close both the first and the last sonatas – the latter in combination with a solemn Sarabanda, French in all but the title.

The last movement of the fifth sonata, titled La caccia – with its characteristic 6/8 meter and D major key – is another homage to a very popular French musical topic, the description of a hunt – one to which Cartier would later devote a full section of examples from French composers in his L’art du violon (1798).

The evident virtuosity that characterizes this collection shows also another important model for Guido’s sonatas, the works by Antonio Vivaldi, whose violin sonatas and concertos had gained huge popularity in Paris in the 1720s. While in his first publication of petit motets in 1707, dedicated to Philippe d’Orléans – one of the earliest examples of this genre including a solo violin as an accompanying instrument – Guido had already included solo violin sections using triple-stops, in the 1726 sonatas he introduces series of chords and extended, virtuosic 32nd-note passages, such as those that fill the opening Preludio of the third sonata, the final Gavotta of the first sonata, or the Vivace of the same sonata in which the arpeggios extend to the fifth position. It was after looking at these sonatas that Moser concluded that “without doubt Guido must have been a very talented violinist.”

As this collection of sonatas, here recorded for the first time, demonstrates, the activity of Neapolitan musicians in France had a significant impact on the development of the French instrumental tradition and played a critical part in the formation of a new aesthetic sensibility.

01. Sonata I: I. Adagio-Un poco Andante

02. Sonata I: II. Vivace

03. Sonata I: III. Adagio

04. Sonata I: IV. Allegro e non presto

05. Sonata I: V. Gavotta

06. Sonata II: I. Adagio

07. Sonata II: II. Allegro e non presto

08. Sonata II: III. Gratioso

09. Sonata II: IV. Allegro

10. Sonata III: I. Preludio Adagio. Un poco Andante

11. Sonata III: II. Allegro

12. Sonata III: III. Piacevole

13. Sonata III: IV. Allegro

14. Sonata IV: I. Adagio

15. Sonata IV: II. Allegro

16. Sonata IV: III. Adagio. Allegro. Adagio

17. Sonata IV: IV. Allegro

18. Sonata, vol. I: I. Adagio

19. Sonata, vol. I: II. Allegro

20. Sonata, vol. I: III. Sarabanda

21. Sonata, vol. I: IV. Gavotta

22. Sonata V: I. Adagio

23. Sonata V: II. Allegro e Spiccato

24. Sonata V: III. Adagio

25. Sonata V: IV. La caccia. Allegro

The reception of new Italian music in France at the beginning of the 18th century gained an extraordinary momentum in connection with profound social and political developments. The arrival of new music and, above all, of talented virtuosi from Italy stimulated an intense debate over the respective aesthetic value of the Italian and French musical traditions in which Italian music was seen as the aural representation of a new society that aspired to take distance from the court of Louis XIV.

Several Italian musicians who arrived in Paris at the beginning of the 18th century found in the new cultural climate of the French capital the perfect conditions for their successful careers. They participated to the rich artistic exchanges between the two nations and contributed to the spread of the Italian violin sonata in France. The fact that many of these virtuosi active in Paris were coming from Naples, although often unnoticed by modern historiographical narratives, was not a coincidence: it was the consequence of the advancement of the Neapolitan string tradition, but it also derived from the new political liaisons between Naples and Paris. Between 1702 and 1707 the Kingdom of Naples came temporarily under the control of the French monarchy; the new dominion favored the contacts between the two capitals and opened up career opportunities to Neapolitan musicians.

Giovanni Antonio Guido (ca. 1675- after 1733) was probably the first Neapolitan musician to move to Paris, where he achieved a high reputation both as a performer and composer. As the tile page of his collection of Mottetti (1707) attests and documents about his admission at the conservatory confirm, Guido was born in Genoa around 1675. He then moved to Naples where he studied violin at the Conservatory of S. Maria della Pietà dei Turchini. After completing his studies in 1690, Guido entered the prestigious ensemble of the Royal Chapel; his name appears in the official list of personnel as a regular member of the chapel from September 1698 through December 1701. In January 1702 a dispatch from the Cappellano Maggiore announced his replacement. It is therefore around that time that we can date Guido’s move to Paris.

In the French capital the Neapolitan violinist rapidly became one of the protagonists of the profound changes that impacted French artistic life and influenced the development of music aesthetics and criticism. The first mention of his activity in Paris is in connection with the patronage of Italian artists by the duke Philippe d’Orléans. The complex personality and powerful position of Philippe d’Orléans made him the leader of the Italianate party in the French capital. In a time when the confrontation over musical taste had political overtones, Philippe’s patronage of Giovanni Antonio Guido and of other Italian musicians became the expression of his opposition to the stifling politics of Louis XIV’s regime and projected his crucial role in the renovation of French high society.

The future Regent of France put together an Italian ensemble unique in France, formed by two singers and two violinists of Italian training and various other French musicians hired on the occasion. It was with this ensemble that Guido made his debut in France. In November 1703 the visit of the Queen of England at Fontainebleau included a concert with the participation of the two castrati, Pasqualino Tiepoli and Pasqualino Betti — whom the Duc d’Orléans had borrowed from Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni — Guido and Baptiste Anet playing violin and Joseph Marchand, “Basse de violon.”

Without doubt the protection of this powerful patron gave Guido the opportunity for rapidly advancing his career. Again, in September 1704 the Mercure Galant gave notice of a concert at the residence of the duchesse du Maine at Sceaux during which Guido had one of his vocal pieces performed before Louis XIV. In less than two years after his departure from Naples, Guido – now usually mentioned with the appellative of Antonio – was therefore at the center of the Parisian musical world both as a performer and composer. That his name was well known to the public of Paris is evident from his inclusion among the “virtuosi de l’Italie” in the second part of Lecerf de la Viéville’s Comparaison de la musique italienne e de la musique françoise, which appeared in 1705. A further testimony to the fame he enjoyed came in the annotations added to the English translation of François Raguenet’s Parallèle des Italiens et des Français en ce qui regarde la musique e les opéras in 1709 — later included by John Hawkins in his A General History of the Science and Practice of Music — in which Guido was listed among the most prominent musicians of the time.

With the beginning of Philippe d’Orléans’ regency in 1715 and the transfer of the court to the Palais Royal, the heart of the political, economic, and administrative life of France moved from Versailles to Paris. An emerging aristocracy of wealth embraced new artistic expressions, becoming an enthusiastic promoter of cultural events, and the practice of organizing public entertainments began to spread. Pierre Crozat (1661-1740), belonged to one of the wealthiest families in France – his father was a banker in Toulouse, and his brother, Antoine, “the wealthiest man in Paris,” had received from the king the exclusive trading and governing rights to the territories of Louisiana. Between 1715 and 1725 Pierre held regular concerts at his splendid residence in rue Richelieu, events that attracted a public of intellectuals, nobles, and music amateurs, as well as professional artists and musicians. The atmosphere of those gatherings survives in several drawings made by the famous painter Antoine Watteau. Indeed, Giovanni Antonio Guido’s participation in these soirees is confirmed by a small portrait of the musician realized by Watteau, probably around 1720. In the 1720s and 1730s Guido’s music was also performed at the Concert Spirituel and at other important concert venues in the French capital.

The collection that Giovanni Antonio Guido published in 1726 – dedicated to Louis d’Orléans, the son of the late Regent – marks a shift toward the assimilation of the French and Italian style in the so-called goûts réunis (“reunited tastes”).

The choice of solo violin sonatas already reveals the composer’s intention to adopt the most progressive language. While several of the slow movements recall the Corellian style – the elegant opening movement of the fifth sonata offers even an example of a quasi-Handelian ‘classicism’ – the adoption of tempo indications such as Piacevole or Gratioso, show a tendency toward a more marked galant style, possibly mediated by the influence of other Italian successful composers active in Paris at the time, such as Michele Mascitti.

Without completely abandoning the characteristics of his previous writing, Guido introduces in these sonatas traits of the French style: a more flowing melodic line is given to the violin, while the bass often accompanies it with simpler harmonies and clear-cut phrases, but sometimes intervening in an active dialogue with the violin, as in the Allegro e non Presto of the second sonata. The French elements emerge in several sonatas of the collection, for instance in the inclusion of dances such as the gavottas that close both the first and the last sonatas – the latter in combination with a solemn Sarabanda, French in all but the title.

The last movement of the fifth sonata, titled La caccia – with its characteristic 6/8 meter and D major key – is another homage to a very popular French musical topic, the description of a hunt – one to which Cartier would later devote a full section of examples from French composers in his L’art du violon (1798).

The evident virtuosity that characterizes this collection shows also another important model for Guido’s sonatas, the works by Antonio Vivaldi, whose violin sonatas and concertos had gained huge popularity in Paris in the 1720s. While in his first publication of petit motets in 1707, dedicated to Philippe d’Orléans – one of the earliest examples of this genre including a solo violin as an accompanying instrument – Guido had already included solo violin sections using triple-stops, in the 1726 sonatas he introduces series of chords and extended, virtuosic 32nd-note passages, such as those that fill the opening Preludio of the third sonata, the final Gavotta of the first sonata, or the Vivace of the same sonata in which the arpeggios extend to the fifth position. It was after looking at these sonatas that Moser concluded that “without doubt Guido must have been a very talented violinist.”

As this collection of sonatas, here recorded for the first time, demonstrates, the activity of Neapolitan musicians in France had a significant impact on the development of the French instrumental tradition and played a critical part in the formation of a new aesthetic sensibility.

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads