Michele Carreca - Denis Gaultier and Ennemond Gaultier: À Rome 1676 (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Michele Carreca

- Title: Denis Gaultier and Ennemond Gaultier: À Rome 1676

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

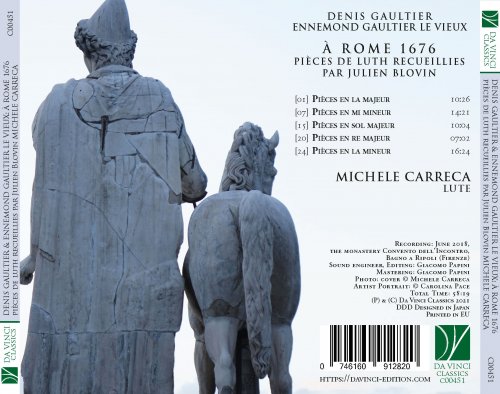

- Total Time: 00:58:20

- Total Size: 276 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Prélude in A Major

02. Courante et double in A Major

03. Sarabande in A Major

04. Courante in A Major

05. Gigue in A Major

06. Chacconne in A Major

07. Prélude in E Minor

08. Courante I in E Minor

09. Courante II in E Minor

10. Pavanne in E Minor

11. Courante III in E Minor

12. Courante IV in E Minor

13. Sarabande in E Minor

14. Gigue in E Minor

15. Prélude in G Major

16. Courante I in G Major

17. Courante II in G Major

18. Sarabande in G Major

19. Gigue in G Major

20. Courante I in D Major

21. Courante II in D Major

22. Sarabande in D Major

23. Gigue in D Major

24. Prélude in A Minor

25. Pavanne in A Minor

26. Courante et double I in A Minor

27. Sarabande I in A Minor

28. Courante in A Minor

29. Allemande in A Minor

30. Courante et double II in A Minor

31. Sarabande II in A Minor

In today’s hyper-connected world, high-speed transportation may bring us from one point of the globe to another in very little time, and, even more strikingly, video-calls can instantly connect us with people living in any given place of the planet. We may therefore find it difficult to imagine how people, ideas and culture moved in the past, when such facilities were not available. Yet, as soon as we start to explore the experiences of our ancestors, we discover that culture and people did travel a lot, and that art could be disseminated in rather adventurous fashions. And this applies also to fields in which local traditions determined what was fashionable or not; these traditions, however, could be exported even in remote areas, and establish new traditions and new fashions in their turn.

Among the many documents bearing witness to the mobility of art and culture, manuscripts represent invaluable sources allowing us to trace the itinerary of certain works through geography and history. Such is the case with the manuscript which forms the object of the present recording.

In its first page, it bears an inscription, which reads: Pièce de luth: Julien Blouin / A Rome 1676. It contains lute tablatures, and it is subtly intriguing for a number of reasons.

The scribe is therefore Julien Blouin (or Blovin, or Bloivin, c. 1650-1715). He was a Frenchman, who was active in Rome since 1672 both as a lutenist and lute teacher, but also as a member of the Papal Guards; he reportedly played the lute “cleanly and clearly”, as witnessed by Johann Friedrich A. von Uffenbach.

In 1676, Prince Ferdinand August Leopold Lobkowitz (1655-1715) came of age, and, as was customary at the time, it is rather likely that he may have embarked in the famous “Grand Tour”, visiting the great capitals and the most beautiful cities of Europe; Rome was of course an integral component of the tour. It is possible that, on that occasion, he met Blouin, who taught lute to many members of the aristocracy, especially those from foreign countries. It has been argued (though it remains to be demonstrated) that the manuscript under consideration might have some connection with this Prince, since, in the holdings of the Lobkowitz library are found numerous works for the lute and guitar, some of which were written by Denis Gaultier (Livre de Tablature and Pièces de luth). Another of Blouin’s manuscripts, by the title of Pièces de luth. Julien Blovin à Rome 1673 is currently found in Prague, and still other manuscript sources by Blouin’s hand have been identified (one with the same date, for baroque guitar and angelique, and others in collections linked to Polish patrons).

Though the origins of this manuscript still inhabit the realm of hypotheses, this only increases the fascination of a marvellous collection. It is beautiful from a merely aesthetic point of view, thanks to Blouin’s neat calligraphy and to the evident care he devoted to this purpose. But it is especially remarkable for the music it contains.

The works it includes were mainly composed by the two Gaultier cousins, Ennemond, also known as Gaultier le Vieux or Gaultier de Lyon (c. 1575-1651) and Denis, also known as Gaultier le Jeune or Gaultier de Paris (1597 or 1602/3-1672). As happens rather frequently with families of artists, it may be difficult to attribute a particular work to one or another member of the family. First of all, contemporaries might refer indifferently to any one of them by the family name, thus making it difficult to assign a piece or some information to a particular individual. Secondly, and especially when a family member taught another, there can be a direct and sometimes very pronounced influence, which complicates attribution due to the similar style of their works.

This is what happens in a paradigmatic fashion with the two Gaultiers (indeed, matters are further complicated by the fact that there were at least two more Gaultiers, roughly contemporaries of Ennemond and Denis, who were excellent lutenists in turn, although seemingly unrelated with them).

Biographical information about Ennemond is scantier than that about his younger cousin. His nickname as “Gaultier de Lyon” refers to his region of origin, the Dauphiné; he was probably born in Villette, in a “honorable” family. At 7, he became a page of “Madame de Montmorency”, wife to Earl Henry I of Montmorency Damville. The earl was also the King’s lieutenant in Languedoc, where probably Ennemond received his first musical instruction. Later (probably around 1610), the youth was called in the service of Maria de’ Medici, the Queen Mother. This was probably due to his excellency as a lute player; Ennemond gained particular recognition thanks to an especially famous Sarabande he had composed inspired by a dance performed at court by Brazilian natives. In Paris, he became a student of René Mésangeau (fl. 1567-1638); to honour his teacher’s memory, Ennemond would later compose Le Tombeau de Mésangeau, the first known example of instrumental “Tombeau”. In the following years, Ennemond established his position at court firmly; he reportedly refused some sinecures he had been offered, out of pride and independence.

Ennemond’s fame travelled long both in space and in time. He was appreciated by musicians of the standing of Mersenne, by statesmen such as Richelieu, and his journey to England was extremely successful; Ennemond’s genius would be remembered for years after his death.

In spite of this, the last years of his life were marked by grave family and financial problems, due to the trust he misplaced in his former servant and then mistress, who seemingly took advantage of his frailty.

Ennemond’s works are currently known only thanks to his cousin’s efforts: in 1672, Denis included fifteen pieces by Ennemond in one of his most successful publications, the Livre de Tablature. In this case, the composer is identified as “Vieux Gautier”; in other cases, his paternity of individual pieces has been surmised, but could not be definitively proved.

Denis, to whom we owe what we know about Ennemond, was born probably in Paris; he certainly studied there, probably with Ennemond himself as concerns the lute, and with Charles Racquet (c. 1590-1664) as concerns composition; Racquet was the organist at the Cathedral of Notre Dame. Denis married a well-to-do lady, Françoise Daucourt, but would generously support her numerous sisters when they became orphaned a few years later.

Denis’ fame as a lutenist increased progressively, and reached its climax in the 1650s, when Anne-Achille de Chambré, a wealthy bourgeois with important functions in the State, sponsored the realization of a magnificent manuscript, La Rhétorique des Dieux, intended as a homage to Denis’ skill, to his teaching and to his ability, and collecting some of his works organized admirably with references to Greek antiquity. The manuscript is adorned with beautiful illustrations, including a portrait of Denis himself. If the manuscript preserves the memory of the intellectual circles in which Denis moved, he was not less welcome among the aristocracy of the era. He performed for royals from all over Europe, and was familiar with the French monarchs, even though he did not have official appointments at court. He was also very appreciated as a teacher, and was capable, as a pedagogue, of fostering the development of very young musicians, such as the extremely gifted Marianne Plantier.

Denis Gaultier died in 1672, and was deeply lamented by his colleagues who paid homage to his genius with Tombeaux and eulogies.

Denis’ works include collections such as Pièces de luth (1670) and Livre de tablature (1672), each containing both written instruction on how to play the lute and musical pieces, and is unanimously regarded as one of the greatest representative of the French lute school. The esteem in which he was held is witnessed by the numerous transcriptions of his works realized for keyboard instruments, and he is acknowledged as having influenced great musicians such as Johann Jakob Froberger.

All the works recorded here are inspired by dance music and forms; the individual movements are juxtaposed to each other so as to form suites, whose main unifying element is their common key. In this recording are also included a few movements which were not comprised in the original manuscript, but whose presence was deemed advisable for musical reasons; such integrations have been made taking, as the starting point, other manuscripts which have pieces in common with this one. The Preludes are non-measured, and frequently encompass the entire range of the lute; all dances are beautifully characterized, and they frequently eschew all rigid or symmetrical structures, while displaying regularity in the recurrence of well-shaped phrases. The style of both composer is perfectly tailored to the needs and potential of their instrument, of which it displays the full gamut of affective resources, also thanks to a skillful use of harmonic refinements.

Together, the pieces recorded here constitute a fascinating immersion into a world which prized beauty and elegance, expressivity and wonder, and in which the geniuses of the era could disseminate the fruits of their creativity among those who could appreciate their value, and contribute to preserve it until present day.

01. Prélude in A Major

02. Courante et double in A Major

03. Sarabande in A Major

04. Courante in A Major

05. Gigue in A Major

06. Chacconne in A Major

07. Prélude in E Minor

08. Courante I in E Minor

09. Courante II in E Minor

10. Pavanne in E Minor

11. Courante III in E Minor

12. Courante IV in E Minor

13. Sarabande in E Minor

14. Gigue in E Minor

15. Prélude in G Major

16. Courante I in G Major

17. Courante II in G Major

18. Sarabande in G Major

19. Gigue in G Major

20. Courante I in D Major

21. Courante II in D Major

22. Sarabande in D Major

23. Gigue in D Major

24. Prélude in A Minor

25. Pavanne in A Minor

26. Courante et double I in A Minor

27. Sarabande I in A Minor

28. Courante in A Minor

29. Allemande in A Minor

30. Courante et double II in A Minor

31. Sarabande II in A Minor

In today’s hyper-connected world, high-speed transportation may bring us from one point of the globe to another in very little time, and, even more strikingly, video-calls can instantly connect us with people living in any given place of the planet. We may therefore find it difficult to imagine how people, ideas and culture moved in the past, when such facilities were not available. Yet, as soon as we start to explore the experiences of our ancestors, we discover that culture and people did travel a lot, and that art could be disseminated in rather adventurous fashions. And this applies also to fields in which local traditions determined what was fashionable or not; these traditions, however, could be exported even in remote areas, and establish new traditions and new fashions in their turn.

Among the many documents bearing witness to the mobility of art and culture, manuscripts represent invaluable sources allowing us to trace the itinerary of certain works through geography and history. Such is the case with the manuscript which forms the object of the present recording.

In its first page, it bears an inscription, which reads: Pièce de luth: Julien Blouin / A Rome 1676. It contains lute tablatures, and it is subtly intriguing for a number of reasons.

The scribe is therefore Julien Blouin (or Blovin, or Bloivin, c. 1650-1715). He was a Frenchman, who was active in Rome since 1672 both as a lutenist and lute teacher, but also as a member of the Papal Guards; he reportedly played the lute “cleanly and clearly”, as witnessed by Johann Friedrich A. von Uffenbach.

In 1676, Prince Ferdinand August Leopold Lobkowitz (1655-1715) came of age, and, as was customary at the time, it is rather likely that he may have embarked in the famous “Grand Tour”, visiting the great capitals and the most beautiful cities of Europe; Rome was of course an integral component of the tour. It is possible that, on that occasion, he met Blouin, who taught lute to many members of the aristocracy, especially those from foreign countries. It has been argued (though it remains to be demonstrated) that the manuscript under consideration might have some connection with this Prince, since, in the holdings of the Lobkowitz library are found numerous works for the lute and guitar, some of which were written by Denis Gaultier (Livre de Tablature and Pièces de luth). Another of Blouin’s manuscripts, by the title of Pièces de luth. Julien Blovin à Rome 1673 is currently found in Prague, and still other manuscript sources by Blouin’s hand have been identified (one with the same date, for baroque guitar and angelique, and others in collections linked to Polish patrons).

Though the origins of this manuscript still inhabit the realm of hypotheses, this only increases the fascination of a marvellous collection. It is beautiful from a merely aesthetic point of view, thanks to Blouin’s neat calligraphy and to the evident care he devoted to this purpose. But it is especially remarkable for the music it contains.

The works it includes were mainly composed by the two Gaultier cousins, Ennemond, also known as Gaultier le Vieux or Gaultier de Lyon (c. 1575-1651) and Denis, also known as Gaultier le Jeune or Gaultier de Paris (1597 or 1602/3-1672). As happens rather frequently with families of artists, it may be difficult to attribute a particular work to one or another member of the family. First of all, contemporaries might refer indifferently to any one of them by the family name, thus making it difficult to assign a piece or some information to a particular individual. Secondly, and especially when a family member taught another, there can be a direct and sometimes very pronounced influence, which complicates attribution due to the similar style of their works.

This is what happens in a paradigmatic fashion with the two Gaultiers (indeed, matters are further complicated by the fact that there were at least two more Gaultiers, roughly contemporaries of Ennemond and Denis, who were excellent lutenists in turn, although seemingly unrelated with them).

Biographical information about Ennemond is scantier than that about his younger cousin. His nickname as “Gaultier de Lyon” refers to his region of origin, the Dauphiné; he was probably born in Villette, in a “honorable” family. At 7, he became a page of “Madame de Montmorency”, wife to Earl Henry I of Montmorency Damville. The earl was also the King’s lieutenant in Languedoc, where probably Ennemond received his first musical instruction. Later (probably around 1610), the youth was called in the service of Maria de’ Medici, the Queen Mother. This was probably due to his excellency as a lute player; Ennemond gained particular recognition thanks to an especially famous Sarabande he had composed inspired by a dance performed at court by Brazilian natives. In Paris, he became a student of René Mésangeau (fl. 1567-1638); to honour his teacher’s memory, Ennemond would later compose Le Tombeau de Mésangeau, the first known example of instrumental “Tombeau”. In the following years, Ennemond established his position at court firmly; he reportedly refused some sinecures he had been offered, out of pride and independence.

Ennemond’s fame travelled long both in space and in time. He was appreciated by musicians of the standing of Mersenne, by statesmen such as Richelieu, and his journey to England was extremely successful; Ennemond’s genius would be remembered for years after his death.

In spite of this, the last years of his life were marked by grave family and financial problems, due to the trust he misplaced in his former servant and then mistress, who seemingly took advantage of his frailty.

Ennemond’s works are currently known only thanks to his cousin’s efforts: in 1672, Denis included fifteen pieces by Ennemond in one of his most successful publications, the Livre de Tablature. In this case, the composer is identified as “Vieux Gautier”; in other cases, his paternity of individual pieces has been surmised, but could not be definitively proved.

Denis, to whom we owe what we know about Ennemond, was born probably in Paris; he certainly studied there, probably with Ennemond himself as concerns the lute, and with Charles Racquet (c. 1590-1664) as concerns composition; Racquet was the organist at the Cathedral of Notre Dame. Denis married a well-to-do lady, Françoise Daucourt, but would generously support her numerous sisters when they became orphaned a few years later.

Denis’ fame as a lutenist increased progressively, and reached its climax in the 1650s, when Anne-Achille de Chambré, a wealthy bourgeois with important functions in the State, sponsored the realization of a magnificent manuscript, La Rhétorique des Dieux, intended as a homage to Denis’ skill, to his teaching and to his ability, and collecting some of his works organized admirably with references to Greek antiquity. The manuscript is adorned with beautiful illustrations, including a portrait of Denis himself. If the manuscript preserves the memory of the intellectual circles in which Denis moved, he was not less welcome among the aristocracy of the era. He performed for royals from all over Europe, and was familiar with the French monarchs, even though he did not have official appointments at court. He was also very appreciated as a teacher, and was capable, as a pedagogue, of fostering the development of very young musicians, such as the extremely gifted Marianne Plantier.

Denis Gaultier died in 1672, and was deeply lamented by his colleagues who paid homage to his genius with Tombeaux and eulogies.

Denis’ works include collections such as Pièces de luth (1670) and Livre de tablature (1672), each containing both written instruction on how to play the lute and musical pieces, and is unanimously regarded as one of the greatest representative of the French lute school. The esteem in which he was held is witnessed by the numerous transcriptions of his works realized for keyboard instruments, and he is acknowledged as having influenced great musicians such as Johann Jakob Froberger.

All the works recorded here are inspired by dance music and forms; the individual movements are juxtaposed to each other so as to form suites, whose main unifying element is their common key. In this recording are also included a few movements which were not comprised in the original manuscript, but whose presence was deemed advisable for musical reasons; such integrations have been made taking, as the starting point, other manuscripts which have pieces in common with this one. The Preludes are non-measured, and frequently encompass the entire range of the lute; all dances are beautifully characterized, and they frequently eschew all rigid or symmetrical structures, while displaying regularity in the recurrence of well-shaped phrases. The style of both composer is perfectly tailored to the needs and potential of their instrument, of which it displays the full gamut of affective resources, also thanks to a skillful use of harmonic refinements.

Together, the pieces recorded here constitute a fascinating immersion into a world which prized beauty and elegance, expressivity and wonder, and in which the geniuses of the era could disseminate the fruits of their creativity among those who could appreciate their value, and contribute to preserve it until present day.

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads