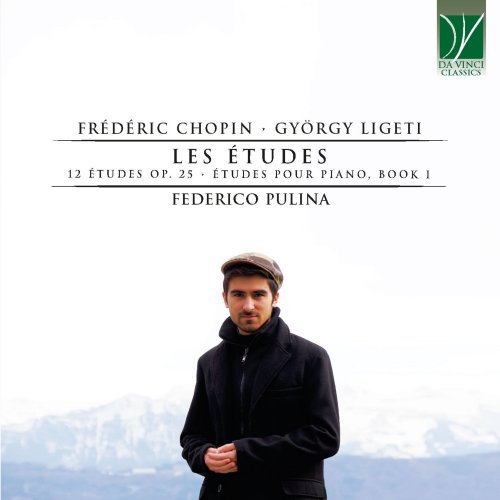

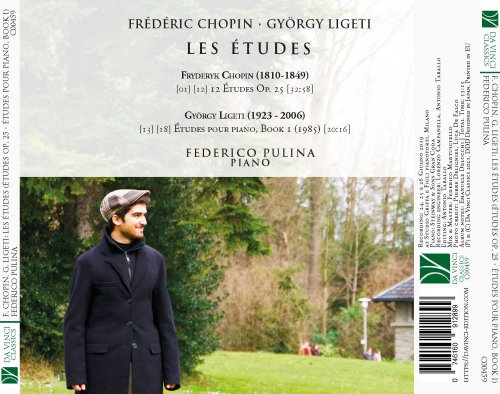

Federico Pulina - Chopin, Ligeti: Les Études (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Federico Pulina

- Title: Chopin, Ligeti: Les Études

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 00:53:15

- Total Size: 169 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 1 in A-Flat Major, Aeolian Harp

02. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 2 in F Minor, The Bees

03. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 3 in F Major, The Horseman

04. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 4 in A Minor, Paganini

05. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 5 in E Minor, Wrong Note

06. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 6 in G-Sharp Minor, Thirds

07. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 7 in C-Sharp Minor, Cello

08. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 8 in D-Flat Major, Sixths

09. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 9 in G-Flat Major, Butterfly

10. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 10 in B Minor, Octave

11. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 11 in A Minor, Winter Wind

12. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 12 in C Minor, Ocean

13. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 1, Désordre. Molto vivace, vigoroso, molto ritmico

14. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 2, Cordes à vide. Andantino rubato, molto tenero

15. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 3, Touches bloquées. Vivacissimo, sempre molto ritmico – Feroce, impetuoso, molto meno vivace – Feroce, estrepitoso – Tempo I

16. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 4, Fanfares. Vivacissimo, molto ritmico

17. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 5, Arc-en-ciel. Andante con eleganza

18. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 6, Automne à Varsovie. Presto cantabile, molto ritmico e flessibile

Chopin’s Études, Liszt’s Études d’exécution transcendante, Debussy’s and Ligeti’s Études: within the boundless literature of Piano Études, some collections have reached, with time, the status of unavoidable classics, thanks to the very high technical and musical level they represent. They therefore left the tiny, and very private, space reserved for “finger gymnastics”, indispensable for pianists wishing to enter the professional ranks. Études are artistic amplifications of the simple technical exercises, and are therefore more appealing than them. In spite of all the contumelies which could be thought of them, the Études by Czerny will always be more interesting and pleasing than bare scales. The results of this pedagogical/artistic operation (which marks the intentions also of an undisputed masterpiece such as Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier) are extremely varied. They range from pragmatic usefulness (Czerny, Clementi, Heller, Cramer) to the most delirious utopias (Alkan, Mereaux, Godowsky…). Only the above-cited collections, along with many others which are not mentioned here, distinguished themselves for their balance between instrumental mechanicism and artistic inspiration, without detriment for either component.

To be more precise, what distinguishes Chopin’s Études op. 25 from one of the extremely numerous coeval collections of études, such as for example Czerny’s 24 Grandes études caractéristiques op. 692? In all likelihood, a fundamental role is played by the overcoming of a Biedermeier idea of piano technique, in function of an entirely innovative expressive and timbral research. It suffices to compare op. 25 no. 12, in C minor, with op. 692 no. 20, in the same key and by the title of Les vagues de l’Océan (this is a curious coincidence, since Etude op. 25 no. 12 is known as Ocean Etude in the English-speaking world). One then realizes that the forced, and under some aspects redundant, proportions of Czerny’s Étude are condensed within a very clear and synthetic ABA form by Chopin. This is indebted, for the cleanness of its harmonic and rhetoric conduit, to the second Prelude from the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book One, rather than to the Romantic Études.

Chopin’s operation of synthesis does not regard form only, but also the kind of technical difficulty on which the Étude is built. Just as the modulations are contained within close keys (and are not centrifugal as in op. 692 no. 20, which goes from C minor to C-sharp minor in its central section), so also the technical combinations undergo a reductio ad unum (the change between little finger and thumb on the same note of the arpeggio), whilst Czerny’s Étude requires arpeggios, broken chords, scales, melodies in octaves, leaps and much more.

As in the rest of his output, including the specifically “Polish” one, Chopin has clear compositional references on which he shapes the form of his Études: Bach, and especially his Preludes, and Mozart, as concerns the balance and proportions of the musical phrases.

Moreover, it should not be forgotten that Chopin’s technical approach to the piano is that of a self-taught musician, even if a genius-like one. Therefore, he is not too much indebted to canonic technical stereotypes. This explains why, in his contemporaries’ eyes, pieces such as Etude op. 10 no. 2 must have resembled “devilries for twisting the fingers”, and why the Études represent such a sensational stage in the instrument’s history.

The twelve Études op. 25 were published in 1837 and dedicated to Marie d’Agoult, who, at the time, was Liszt’s partner: to Liszt, Chopin had already dedicated his Études op. 10.

They are ordered following a free tonal scheme, even though some relationships can be observed among them. For example, no. 9 in G-flat major and no. 6 in G-sharp minor end with the dominant chord of the following Études, respectively nos. 10 and 7. These pieces have generally a broader scope than their homologues of op. 10, and are stylistically located in the composer’s full maturity. Suffice it to compare two “slow” Études from the two collections, i.e. op. 10 no. 3 and op. 25 no. 7, to note that, in the latter, the tripartite form is enriched by an introductory instrumental recitative. Moreover, the texture here replaces the simple accompanied melody with a musical discourse based on three sound layers (the melody at the bass and soprano, with an accompaniment in the central register). Similar amplifications are found also in Etude no. 10, whose central section changes both its key and its agogic indications, thus creating a tripartite form identical to that of no. 5, in E minor (a kind of Mazurka exploring the technical possibilities deriving from the finger combination of index and little finger vs. thumb). They can be also observed in Étude no. 11 in A minor, preceded by a very short introduction which presents the piece’s principal theme first monodically, and later as a chorale-like harmonization, brusquely followed by the “real” etude (one of the most dramatic and rhetorically passionate pieces by Chopin). Aphoristic pieces are not missing, similar to certain Preludes: this is the case with Etude no. 2, a delicate perpetuum mobile, or no. 9, on the lightness and grace of the octaves. There are also exquisitely “technical” Études, such as no. 6 on thirds and no. 8 on sixths, or “bravura” pieces (such as no. 3 in F major or no. 4 in A minor, known – not perchance – by the nickname of Paganini, perhaps in consideration of its similarity with the famous eponymous piece in Schumann’s Carnaval). The collection is framed by no. 1, with its timbral research (Aeolian harp, following Schumann’s famous definition of Chopin’s performance style), a very sweet melody revolving around one note and sustained by a vaporous accompaniment of rapid and extremely light arpeggios, and by the already-mentioned no. 12.

If Chopin’s Études are the compositional apotheosis of a genius-like pianist, Ligeti’s Études can be considered as the pianistic apotheosis of a genius-like composer. It is well known that the composer repeatedly stressed that he was not a performer at all. It is therefore all the more surprising that his output of Études (18 in total, divided among three books composed between 1985 and 2001) entered the standard performance repertoire in a stable fashion, along with those by Chopin, Liszt and Rachmaninov.

The first book of Études, recorded here, is made of six pieces, each provided with a poetic title, or referring to the kind of compositional/pianistic technique informing it.

The first three Études are dedicated to Pierre Boulez and explore exquisitely structural questions. The first, Désordre, is a devilish polyrhythmic perpetuum mobile, played by the right hand on the white keys (diatonic scale) and by the left hand on the black keys (pentatonic scale); it requires an absolute independence of the hands. No. 2, Cordes à vide (open strings, with reference to the bowed-string instruments’ tuning) is an Étude on timbre and on the possible technical combinations deriving from the interval of a perfect fifth. These double stops are normally not included in the Études, not even in those by Debussy, who audaciously wrote an Etude on fourths, or by Scriabin who authored one on ninths. No. 3, Touches bloquées, explores some timbral effects created by depressing some keys without letting the corresponding string resonate, or after having let them resonate; therefore, they cannot be depressed by the other hand. The effect is that of a limping rhythm, in spite of the notes’ continuing flow. This technical device had been experimented by Ligeti already in 1976 with his Three Pieces for Two Pianos. If the ear were close to the keyboard, the noise of the finger depressing the muted keys could be noticed, especially towards the piece’s ending.

No. 4, Fanfares, is built on an irregular rhythmic ostinato (3-2-3), repeated no less than 208 times, and inspired by the Turkish musical theory of the aksak. Over it, rapid melodic fragments are superimposed, evoking, albeit very subtly, a quick fanfare of brass instruments. No. 5, Arc-en-ciel, is possibly the most famous of the collection, and the one closest to a certain triadic harmony and to a certain kind of jazz. The overall ternary structure, and the melodic line (descending at first, and ascending later) describe an arc of sorts, thence the title. The last Étude, Automne à Varsovie, is the complex reinterpretation of a Fugue. It is complete and formed by a subject (a chromatic one, modelled after the Baroque Lamento and divided into three musical phrases) undergoing augmentations and diminutions throughout the piece. Three ascending climaxes divide the piece’s three sections. This Étude is dedicated to my Polish friends: it was composed for an important festival of contemporary music taking place in Warsaw, a city which symbolically unites the two composers recorded here, and to which each dedicated an Etude.

Even though the two collections are not frequently combined in recordings, Chopin’s and Ligeti’s Études draw the performer, along with the listener, through impervious challenges up to peaks of exalted instrumental virtuosity. They succeed in the arduous enterprise of transforming the difficult into the beautiful.

01. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 1 in A-Flat Major, Aeolian Harp

02. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 2 in F Minor, The Bees

03. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 3 in F Major, The Horseman

04. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 4 in A Minor, Paganini

05. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 5 in E Minor, Wrong Note

06. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 6 in G-Sharp Minor, Thirds

07. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 7 in C-Sharp Minor, Cello

08. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 8 in D-Flat Major, Sixths

09. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 9 in G-Flat Major, Butterfly

10. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 10 in B Minor, Octave

11. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 11 in A Minor, Winter Wind

12. 12 Études, Op. 25: No. 12 in C Minor, Ocean

13. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 1, Désordre. Molto vivace, vigoroso, molto ritmico

14. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 2, Cordes à vide. Andantino rubato, molto tenero

15. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 3, Touches bloquées. Vivacissimo, sempre molto ritmico – Feroce, impetuoso, molto meno vivace – Feroce, estrepitoso – Tempo I

16. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 4, Fanfares. Vivacissimo, molto ritmico

17. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 5, Arc-en-ciel. Andante con eleganza

18. Études pour piano, Book 1: No. 6, Automne à Varsovie. Presto cantabile, molto ritmico e flessibile

Chopin’s Études, Liszt’s Études d’exécution transcendante, Debussy’s and Ligeti’s Études: within the boundless literature of Piano Études, some collections have reached, with time, the status of unavoidable classics, thanks to the very high technical and musical level they represent. They therefore left the tiny, and very private, space reserved for “finger gymnastics”, indispensable for pianists wishing to enter the professional ranks. Études are artistic amplifications of the simple technical exercises, and are therefore more appealing than them. In spite of all the contumelies which could be thought of them, the Études by Czerny will always be more interesting and pleasing than bare scales. The results of this pedagogical/artistic operation (which marks the intentions also of an undisputed masterpiece such as Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier) are extremely varied. They range from pragmatic usefulness (Czerny, Clementi, Heller, Cramer) to the most delirious utopias (Alkan, Mereaux, Godowsky…). Only the above-cited collections, along with many others which are not mentioned here, distinguished themselves for their balance between instrumental mechanicism and artistic inspiration, without detriment for either component.

To be more precise, what distinguishes Chopin’s Études op. 25 from one of the extremely numerous coeval collections of études, such as for example Czerny’s 24 Grandes études caractéristiques op. 692? In all likelihood, a fundamental role is played by the overcoming of a Biedermeier idea of piano technique, in function of an entirely innovative expressive and timbral research. It suffices to compare op. 25 no. 12, in C minor, with op. 692 no. 20, in the same key and by the title of Les vagues de l’Océan (this is a curious coincidence, since Etude op. 25 no. 12 is known as Ocean Etude in the English-speaking world). One then realizes that the forced, and under some aspects redundant, proportions of Czerny’s Étude are condensed within a very clear and synthetic ABA form by Chopin. This is indebted, for the cleanness of its harmonic and rhetoric conduit, to the second Prelude from the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book One, rather than to the Romantic Études.

Chopin’s operation of synthesis does not regard form only, but also the kind of technical difficulty on which the Étude is built. Just as the modulations are contained within close keys (and are not centrifugal as in op. 692 no. 20, which goes from C minor to C-sharp minor in its central section), so also the technical combinations undergo a reductio ad unum (the change between little finger and thumb on the same note of the arpeggio), whilst Czerny’s Étude requires arpeggios, broken chords, scales, melodies in octaves, leaps and much more.

As in the rest of his output, including the specifically “Polish” one, Chopin has clear compositional references on which he shapes the form of his Études: Bach, and especially his Preludes, and Mozart, as concerns the balance and proportions of the musical phrases.

Moreover, it should not be forgotten that Chopin’s technical approach to the piano is that of a self-taught musician, even if a genius-like one. Therefore, he is not too much indebted to canonic technical stereotypes. This explains why, in his contemporaries’ eyes, pieces such as Etude op. 10 no. 2 must have resembled “devilries for twisting the fingers”, and why the Études represent such a sensational stage in the instrument’s history.

The twelve Études op. 25 were published in 1837 and dedicated to Marie d’Agoult, who, at the time, was Liszt’s partner: to Liszt, Chopin had already dedicated his Études op. 10.

They are ordered following a free tonal scheme, even though some relationships can be observed among them. For example, no. 9 in G-flat major and no. 6 in G-sharp minor end with the dominant chord of the following Études, respectively nos. 10 and 7. These pieces have generally a broader scope than their homologues of op. 10, and are stylistically located in the composer’s full maturity. Suffice it to compare two “slow” Études from the two collections, i.e. op. 10 no. 3 and op. 25 no. 7, to note that, in the latter, the tripartite form is enriched by an introductory instrumental recitative. Moreover, the texture here replaces the simple accompanied melody with a musical discourse based on three sound layers (the melody at the bass and soprano, with an accompaniment in the central register). Similar amplifications are found also in Etude no. 10, whose central section changes both its key and its agogic indications, thus creating a tripartite form identical to that of no. 5, in E minor (a kind of Mazurka exploring the technical possibilities deriving from the finger combination of index and little finger vs. thumb). They can be also observed in Étude no. 11 in A minor, preceded by a very short introduction which presents the piece’s principal theme first monodically, and later as a chorale-like harmonization, brusquely followed by the “real” etude (one of the most dramatic and rhetorically passionate pieces by Chopin). Aphoristic pieces are not missing, similar to certain Preludes: this is the case with Etude no. 2, a delicate perpetuum mobile, or no. 9, on the lightness and grace of the octaves. There are also exquisitely “technical” Études, such as no. 6 on thirds and no. 8 on sixths, or “bravura” pieces (such as no. 3 in F major or no. 4 in A minor, known – not perchance – by the nickname of Paganini, perhaps in consideration of its similarity with the famous eponymous piece in Schumann’s Carnaval). The collection is framed by no. 1, with its timbral research (Aeolian harp, following Schumann’s famous definition of Chopin’s performance style), a very sweet melody revolving around one note and sustained by a vaporous accompaniment of rapid and extremely light arpeggios, and by the already-mentioned no. 12.

If Chopin’s Études are the compositional apotheosis of a genius-like pianist, Ligeti’s Études can be considered as the pianistic apotheosis of a genius-like composer. It is well known that the composer repeatedly stressed that he was not a performer at all. It is therefore all the more surprising that his output of Études (18 in total, divided among three books composed between 1985 and 2001) entered the standard performance repertoire in a stable fashion, along with those by Chopin, Liszt and Rachmaninov.

The first book of Études, recorded here, is made of six pieces, each provided with a poetic title, or referring to the kind of compositional/pianistic technique informing it.

The first three Études are dedicated to Pierre Boulez and explore exquisitely structural questions. The first, Désordre, is a devilish polyrhythmic perpetuum mobile, played by the right hand on the white keys (diatonic scale) and by the left hand on the black keys (pentatonic scale); it requires an absolute independence of the hands. No. 2, Cordes à vide (open strings, with reference to the bowed-string instruments’ tuning) is an Étude on timbre and on the possible technical combinations deriving from the interval of a perfect fifth. These double stops are normally not included in the Études, not even in those by Debussy, who audaciously wrote an Etude on fourths, or by Scriabin who authored one on ninths. No. 3, Touches bloquées, explores some timbral effects created by depressing some keys without letting the corresponding string resonate, or after having let them resonate; therefore, they cannot be depressed by the other hand. The effect is that of a limping rhythm, in spite of the notes’ continuing flow. This technical device had been experimented by Ligeti already in 1976 with his Three Pieces for Two Pianos. If the ear were close to the keyboard, the noise of the finger depressing the muted keys could be noticed, especially towards the piece’s ending.

No. 4, Fanfares, is built on an irregular rhythmic ostinato (3-2-3), repeated no less than 208 times, and inspired by the Turkish musical theory of the aksak. Over it, rapid melodic fragments are superimposed, evoking, albeit very subtly, a quick fanfare of brass instruments. No. 5, Arc-en-ciel, is possibly the most famous of the collection, and the one closest to a certain triadic harmony and to a certain kind of jazz. The overall ternary structure, and the melodic line (descending at first, and ascending later) describe an arc of sorts, thence the title. The last Étude, Automne à Varsovie, is the complex reinterpretation of a Fugue. It is complete and formed by a subject (a chromatic one, modelled after the Baroque Lamento and divided into three musical phrases) undergoing augmentations and diminutions throughout the piece. Three ascending climaxes divide the piece’s three sections. This Étude is dedicated to my Polish friends: it was composed for an important festival of contemporary music taking place in Warsaw, a city which symbolically unites the two composers recorded here, and to which each dedicated an Etude.

Even though the two collections are not frequently combined in recordings, Chopin’s and Ligeti’s Études draw the performer, along with the listener, through impervious challenges up to peaks of exalted instrumental virtuosity. They succeed in the arduous enterprise of transforming the difficult into the beautiful.

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads