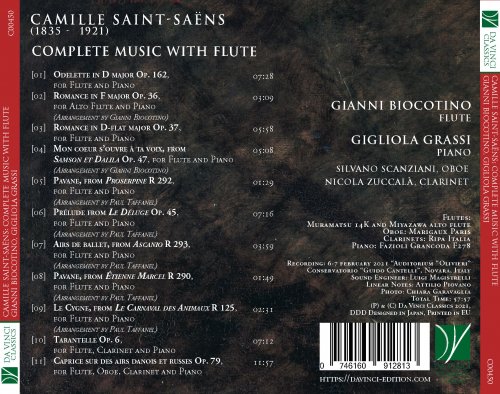

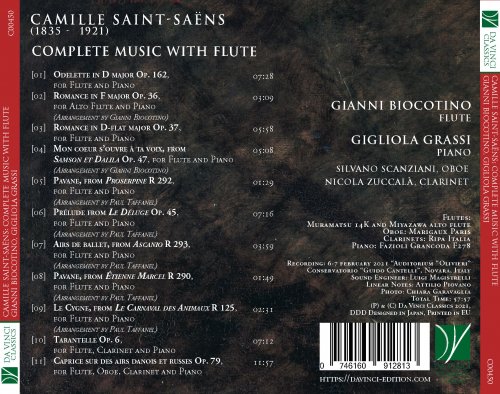

Gianni Biocottino, Gigliola Grassi, Nicola Zuccalà, Silvano Scanziani - Saint-Saëns: Complete Music with Flute (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Gianni Biocottino, Gigliola Grassi, Nicola Zuccalà, Silvano Scanziani

- Title: Saint-Saëns: Complete Music with Flute

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 00:57:56

- Total Size: 225 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Odelette in D Major, Op. 162

02. Romance in F Major, Op. 36 (Arrangement by Gianni Biocotino)

03. Romance in D-Flat Major, Op. 37

04. Samson et Dalila, Op. 47, Act II, Scene 3: "Mon coeur s'ouvre à ta voix" (Arrangement by Gianni Biocotino)

05. Proserpine, R 292: Pavane (Arrangement by Paul Taffanel)

06. Le Déluge, Op. 45: Prélude (Arrangement by Paul Taffanel)

07. Ascanio, R 293: Airs de ballet (Arrangement by Paul Taffanel)

08. Étienne Marcel, R 290: Pavane (Arrangement by Paul Taffanel)

09. Le Carnaval des Animaux, R 125: Le Cygne (Arrangement by Paul Taffanel)

10. Tarantelle, Op. 6

11. Caprice sur des airs danois et russes, Op. 79

This is a singular and intriguing album. It pays homage both to the multifaceted composer Camille Saint-Saëns on the hundredth anniversary of his death, and to Claude-Paul Taffanel (1844-1908). Born in Bordeaux, the latter was first and foremost an excellent flautist, a real pioneer, a kind of a “protective deity” who founded the French flute school and authored, along with his student Ph. Gaubert, an appreciated Méthode complete de la Flûte, published posthumously in Paris in 1923. Moreover, Taffanel was also an orchestra conductor and an author on musical topics (he cooperated to Lavignac’s prestigious encyclopedic work writing the lemmas L’art de diriger and La flûte). Furthermore, he demonstrated his interest in reviving the music of the past.

He was active as a flautist firstly at the Opéra-Comique (1862-64), then, for a long time, at the Opéra (1864-90) and at the Société des Concerts (1865-92). He founded chamber music societies and was nominated a Professor at the Parisian Conservatoire (1893); he occupied that chair until 1906. Before consecrating himself fully to teaching, he performed in acclaimed concert tours in Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and the United Kingdom; he went twice in Russia (1887 and ’89), accompanied by Saint-Saëns. It is not by chance that Camille realized appreciated transcriptions after numerous works by his friend and colleague: these are the object of the present recording. Composers of the standing of Fauré, Widor and Enescu dedicated some of their works to him.

As concerns the long-lived Saint-Saëns, who died, more than octogenarian, in Algiers where he liked to spend the winter months in the last years of his life, his artistic personality is well known. He was a first-rate composer, but also an excellent pianist and renowned organist (he was an extraordinary improviser, who was for many years the titular organist at the console of the Church of the Madeleine). His output ranged from theatrical music to ballet, from sacred music to the symphonic genre, from keyboard music to songs. He left masterpieces such as the opera Samson et Dalila, the symphonic poem Danse macabre, the Suite Algérienne and Symphony no. 3 with organ and two pianos, to mention but the best-known titles. He dedicated a conspicuous part of his artistic resources to chamber music: one could cite just the exotic Havanaise or the funny Carnaval des Animaux.

He participated in intellectual salons, but was also an indefatigable traveller. His frantic activity as a concert musician brought him all around the globe: along with his European concerts, he performed in Russia and the United States, in Egypt, India and South America. He was active as a music critic, as a poet and essay writer, and revealed a multitude of interests including even astronomy. He realized transcriptions after works by Bach and Beethoven, Berlioz, Bizet, Chopin, Gounod, Haydn, Massenet, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Schubert, Wagner and others; he edited works by Charpentier and Gluck, undertaking the edition of Rameau’s complete works. Among his students are the elegant composer Fauré and the organist Gigout.

Here is, therefore, a monographic album dedicated principally to Saint-Saëns’ flute works: a mouth-watering harvest of works, marked generally by a solid feeling for the form, by a constant inventiveness, a harmonic refinement and an undeniable taste.

The CD opens with the graceful Odelette (“Odelet”) op. 162, a work from the composer’s maturity (1920), which is known also in an orchestral version, dedicated to Monsieur François Gaillard and proposed here in an arrangement for flute and piano by the composer. It begins in an almost rhapsodic fashion, in a climate of serene luminosity. The towering theme is soon illuminated by brilliant figurations; a dreamier section with iridescent harmonies leads to the reprise of the beautiful theme, treated in a virtuoso style. Lingering for a long time within the foldings of the minor mode, this works presents itself as streaked with inquietude, and then reconquers the beginning’s serene calm.

In the second and third place are the two coeval and nearly “twin” Romances op. 36 and op. 37 (1874). The first is very short, and was conceived for horn (or cello) and orchestra. It is recorded in an effective transcription for alto flute realized by the performer, Gianni Biocotino. It is a work with a limpid formal structure and a pleasingly singing melodic line, punctuated with refinement especially on the harmonic plane, and enriched by imitations, even within its short duration: it is a small gem very pleasurable to be listened to. As concerns the longer and dreamier op. 37, reclining in the aristocratic key of D-flat major, a cantabile melody by the soloist is offered to our admiration. It spreads itself on a luxuriant harmonic “carpet”, marked by wide arpeggios. A calmer central zone, in the arcadian key of D major, has lyrically moulded gestures and leads to the reprise: it still gives us emotions, until it fades on the rarefied sonorities of the last measures.

An explicit homage to the most famous among Saint-Saëns operatic works could not be missing. Here is, therefore, the effusive and troubling Mon coeur s’ouvre à ta voix, the most celebrated page of the fortunate Samson et Dalila (whose premiere took place at the Grand ducal Theatre of Weimar in 1877). It is a wonderful air of seduction, with a captivating melodicism (Act II), whose sagacious elaboration for the flute realized by Gianni Biocotino renders its fragrance entirely. It also multiplies its resonances and highlights, in the best possible fashion, the curious mix of mysticism and sensuousness which constitutes the peculiar expressive mark of this opera.

The insertion of two archaicizing Pavanes is significant. They are excerpted from the melodramas Proserpine (1887) and Etienne Marcel (1879): these two transcriptions are unavoidably due to Taffanel. The first is a graceful page, with a slightly frail elegance and a melodic line balancing between tonality and modal echoes; the harmonic support, almost ostinato-like, has a staccato phrasing which imitates the harp. Actually, the harp is used in the orchestral version of this scene, that of Proserpine and Renzo (“Va! C’est fort à propos qu’elle les congédie!”, Act I). Curiously, a feature of this Pavane seems to anticipate something of the later Gavotte inserted by Stravinsky within the Suite from his ballet Pulcinella. This is merely an assonance, nothing more; yet it is well recognizable at first hearing. It seems to suggest that Stravinsky did not disdain to remember “good old Camille” in a passage where the flute is protagonist (and this is perhaps a circumstance not happening by chance). As concerns the second, and even shorter Pavane, it reveals a stylistic setting close to the other. It is a real likeness as concerns melody and harmonic functions, portraying an analogous à l’ancienne colour: indeed, the two works might be considered as being almost the calque of each other.

By way of contrast, in the Prélude introducing the oratorio Le Déluge (1876), evoking the Scriptural story of the Flood, sadness predominates initially (Adagio), but later it is a sweet singing style which prevails, enriched by a “Franckian” chromaticism. A very “Bachian” fugato leads into the successive Andantino with a warm lyricism. Here, thanks to Taffanel’s skill, the original expressivity of a solo violin is transposed efficaciously to the flute.

The other two transcriptions are due once more to Taffanel. In Adagio et Variation, on a theme excerpted from the opera Ascanio of 1890, we are led to admire the harmonic iridescence of the fairy-tale initial Adagio, the arcadian beauty of the melody, and the high degree of virtuosity required in the fascinating Andantino. Its phrasing, at times close to the Volière from the Carnaval des Animaux, has sugary, Glockenspiel-like sonorities, while the flute soars with ineffable souplesse over it, as a tightrope walker, leaving us breathless and wondering.

And so we get to the Swan, the best known page of the entire Carnaval des Animaux, the savoury “zoologic fantasy” with caricatural aims, composed in 1886 as a surprise for the traditional mardi-gras concert promoted by cellist Lebouc. Performed in the evening of March 9th, with Saint-Saëns at the piano, it enjoyed immediate success. There were just two performances; the composer forbade all other complete performances, as well as the publication (during his lifetime) of this work which was destined to obtain wide fame. A genius’ work, written with a grain of folly, it is not a realistic bestiaire, but rather a vitriolic mockery of humans, who use to attribute values and defects to the animals. As concerns the Swan (entrusted, in the original, to the cello’s amber sound) it is perhaps the less ironic vignette, maybe out of deference for his friend, the cellist. It certainly is a piece with a great beauty. The cantabile portrays the disembodied animal as if suspended above water, with a slight rippling depicting a pond moved by breeze. We know, however, that the Swan will have to die: indeed, in the last bars, a carillon highlights its fading away.

And here comes to the fore a clarinet, for the youthful and burning Tarantella op. 6 (after an original for the orchestra, the fruit of a barely twenty-two years old Camille who was already a genius). It is a bravura page, irresistible and extroverted, full of fiery rhythms: a true morceau de concert.

Finally, an oboe joins in for the large and sumptuous Caprice of 1887. It is an above-par Quartet, engaging the performers fully and exploring dissimilar expressive horizons. It is admirable in its icy zone, followed by numerous juxtaposed sections, each one rich in appeal. A superb page, where Saint-Saëns engages the flute’s bright timbre with the clarinet’s translucent and the oboe’s stinging ones, supported by a rich piano texture. It is, in sum, a top-class work, closing on the note of a shining joie de vivre sprinkled by a healthy humour, magnificently sealing the entire album. What else?

01. Odelette in D Major, Op. 162

02. Romance in F Major, Op. 36 (Arrangement by Gianni Biocotino)

03. Romance in D-Flat Major, Op. 37

04. Samson et Dalila, Op. 47, Act II, Scene 3: "Mon coeur s'ouvre à ta voix" (Arrangement by Gianni Biocotino)

05. Proserpine, R 292: Pavane (Arrangement by Paul Taffanel)

06. Le Déluge, Op. 45: Prélude (Arrangement by Paul Taffanel)

07. Ascanio, R 293: Airs de ballet (Arrangement by Paul Taffanel)

08. Étienne Marcel, R 290: Pavane (Arrangement by Paul Taffanel)

09. Le Carnaval des Animaux, R 125: Le Cygne (Arrangement by Paul Taffanel)

10. Tarantelle, Op. 6

11. Caprice sur des airs danois et russes, Op. 79

This is a singular and intriguing album. It pays homage both to the multifaceted composer Camille Saint-Saëns on the hundredth anniversary of his death, and to Claude-Paul Taffanel (1844-1908). Born in Bordeaux, the latter was first and foremost an excellent flautist, a real pioneer, a kind of a “protective deity” who founded the French flute school and authored, along with his student Ph. Gaubert, an appreciated Méthode complete de la Flûte, published posthumously in Paris in 1923. Moreover, Taffanel was also an orchestra conductor and an author on musical topics (he cooperated to Lavignac’s prestigious encyclopedic work writing the lemmas L’art de diriger and La flûte). Furthermore, he demonstrated his interest in reviving the music of the past.

He was active as a flautist firstly at the Opéra-Comique (1862-64), then, for a long time, at the Opéra (1864-90) and at the Société des Concerts (1865-92). He founded chamber music societies and was nominated a Professor at the Parisian Conservatoire (1893); he occupied that chair until 1906. Before consecrating himself fully to teaching, he performed in acclaimed concert tours in Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and the United Kingdom; he went twice in Russia (1887 and ’89), accompanied by Saint-Saëns. It is not by chance that Camille realized appreciated transcriptions after numerous works by his friend and colleague: these are the object of the present recording. Composers of the standing of Fauré, Widor and Enescu dedicated some of their works to him.

As concerns the long-lived Saint-Saëns, who died, more than octogenarian, in Algiers where he liked to spend the winter months in the last years of his life, his artistic personality is well known. He was a first-rate composer, but also an excellent pianist and renowned organist (he was an extraordinary improviser, who was for many years the titular organist at the console of the Church of the Madeleine). His output ranged from theatrical music to ballet, from sacred music to the symphonic genre, from keyboard music to songs. He left masterpieces such as the opera Samson et Dalila, the symphonic poem Danse macabre, the Suite Algérienne and Symphony no. 3 with organ and two pianos, to mention but the best-known titles. He dedicated a conspicuous part of his artistic resources to chamber music: one could cite just the exotic Havanaise or the funny Carnaval des Animaux.

He participated in intellectual salons, but was also an indefatigable traveller. His frantic activity as a concert musician brought him all around the globe: along with his European concerts, he performed in Russia and the United States, in Egypt, India and South America. He was active as a music critic, as a poet and essay writer, and revealed a multitude of interests including even astronomy. He realized transcriptions after works by Bach and Beethoven, Berlioz, Bizet, Chopin, Gounod, Haydn, Massenet, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Schubert, Wagner and others; he edited works by Charpentier and Gluck, undertaking the edition of Rameau’s complete works. Among his students are the elegant composer Fauré and the organist Gigout.

Here is, therefore, a monographic album dedicated principally to Saint-Saëns’ flute works: a mouth-watering harvest of works, marked generally by a solid feeling for the form, by a constant inventiveness, a harmonic refinement and an undeniable taste.

The CD opens with the graceful Odelette (“Odelet”) op. 162, a work from the composer’s maturity (1920), which is known also in an orchestral version, dedicated to Monsieur François Gaillard and proposed here in an arrangement for flute and piano by the composer. It begins in an almost rhapsodic fashion, in a climate of serene luminosity. The towering theme is soon illuminated by brilliant figurations; a dreamier section with iridescent harmonies leads to the reprise of the beautiful theme, treated in a virtuoso style. Lingering for a long time within the foldings of the minor mode, this works presents itself as streaked with inquietude, and then reconquers the beginning’s serene calm.

In the second and third place are the two coeval and nearly “twin” Romances op. 36 and op. 37 (1874). The first is very short, and was conceived for horn (or cello) and orchestra. It is recorded in an effective transcription for alto flute realized by the performer, Gianni Biocotino. It is a work with a limpid formal structure and a pleasingly singing melodic line, punctuated with refinement especially on the harmonic plane, and enriched by imitations, even within its short duration: it is a small gem very pleasurable to be listened to. As concerns the longer and dreamier op. 37, reclining in the aristocratic key of D-flat major, a cantabile melody by the soloist is offered to our admiration. It spreads itself on a luxuriant harmonic “carpet”, marked by wide arpeggios. A calmer central zone, in the arcadian key of D major, has lyrically moulded gestures and leads to the reprise: it still gives us emotions, until it fades on the rarefied sonorities of the last measures.

An explicit homage to the most famous among Saint-Saëns operatic works could not be missing. Here is, therefore, the effusive and troubling Mon coeur s’ouvre à ta voix, the most celebrated page of the fortunate Samson et Dalila (whose premiere took place at the Grand ducal Theatre of Weimar in 1877). It is a wonderful air of seduction, with a captivating melodicism (Act II), whose sagacious elaboration for the flute realized by Gianni Biocotino renders its fragrance entirely. It also multiplies its resonances and highlights, in the best possible fashion, the curious mix of mysticism and sensuousness which constitutes the peculiar expressive mark of this opera.

The insertion of two archaicizing Pavanes is significant. They are excerpted from the melodramas Proserpine (1887) and Etienne Marcel (1879): these two transcriptions are unavoidably due to Taffanel. The first is a graceful page, with a slightly frail elegance and a melodic line balancing between tonality and modal echoes; the harmonic support, almost ostinato-like, has a staccato phrasing which imitates the harp. Actually, the harp is used in the orchestral version of this scene, that of Proserpine and Renzo (“Va! C’est fort à propos qu’elle les congédie!”, Act I). Curiously, a feature of this Pavane seems to anticipate something of the later Gavotte inserted by Stravinsky within the Suite from his ballet Pulcinella. This is merely an assonance, nothing more; yet it is well recognizable at first hearing. It seems to suggest that Stravinsky did not disdain to remember “good old Camille” in a passage where the flute is protagonist (and this is perhaps a circumstance not happening by chance). As concerns the second, and even shorter Pavane, it reveals a stylistic setting close to the other. It is a real likeness as concerns melody and harmonic functions, portraying an analogous à l’ancienne colour: indeed, the two works might be considered as being almost the calque of each other.

By way of contrast, in the Prélude introducing the oratorio Le Déluge (1876), evoking the Scriptural story of the Flood, sadness predominates initially (Adagio), but later it is a sweet singing style which prevails, enriched by a “Franckian” chromaticism. A very “Bachian” fugato leads into the successive Andantino with a warm lyricism. Here, thanks to Taffanel’s skill, the original expressivity of a solo violin is transposed efficaciously to the flute.

The other two transcriptions are due once more to Taffanel. In Adagio et Variation, on a theme excerpted from the opera Ascanio of 1890, we are led to admire the harmonic iridescence of the fairy-tale initial Adagio, the arcadian beauty of the melody, and the high degree of virtuosity required in the fascinating Andantino. Its phrasing, at times close to the Volière from the Carnaval des Animaux, has sugary, Glockenspiel-like sonorities, while the flute soars with ineffable souplesse over it, as a tightrope walker, leaving us breathless and wondering.

And so we get to the Swan, the best known page of the entire Carnaval des Animaux, the savoury “zoologic fantasy” with caricatural aims, composed in 1886 as a surprise for the traditional mardi-gras concert promoted by cellist Lebouc. Performed in the evening of March 9th, with Saint-Saëns at the piano, it enjoyed immediate success. There were just two performances; the composer forbade all other complete performances, as well as the publication (during his lifetime) of this work which was destined to obtain wide fame. A genius’ work, written with a grain of folly, it is not a realistic bestiaire, but rather a vitriolic mockery of humans, who use to attribute values and defects to the animals. As concerns the Swan (entrusted, in the original, to the cello’s amber sound) it is perhaps the less ironic vignette, maybe out of deference for his friend, the cellist. It certainly is a piece with a great beauty. The cantabile portrays the disembodied animal as if suspended above water, with a slight rippling depicting a pond moved by breeze. We know, however, that the Swan will have to die: indeed, in the last bars, a carillon highlights its fading away.

And here comes to the fore a clarinet, for the youthful and burning Tarantella op. 6 (after an original for the orchestra, the fruit of a barely twenty-two years old Camille who was already a genius). It is a bravura page, irresistible and extroverted, full of fiery rhythms: a true morceau de concert.

Finally, an oboe joins in for the large and sumptuous Caprice of 1887. It is an above-par Quartet, engaging the performers fully and exploring dissimilar expressive horizons. It is admirable in its icy zone, followed by numerous juxtaposed sections, each one rich in appeal. A superb page, where Saint-Saëns engages the flute’s bright timbre with the clarinet’s translucent and the oboe’s stinging ones, supported by a rich piano texture. It is, in sum, a top-class work, closing on the note of a shining joie de vivre sprinkled by a healthy humour, magnificently sealing the entire album. What else?

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads