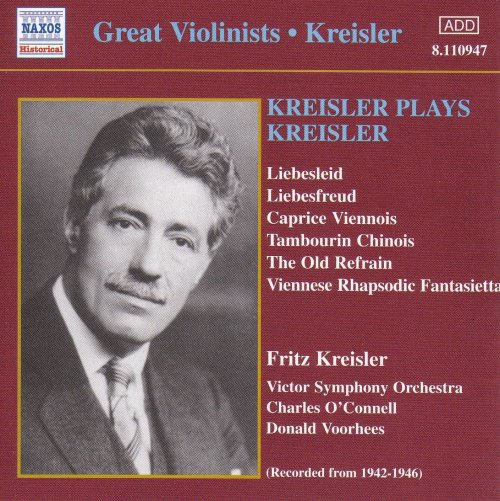

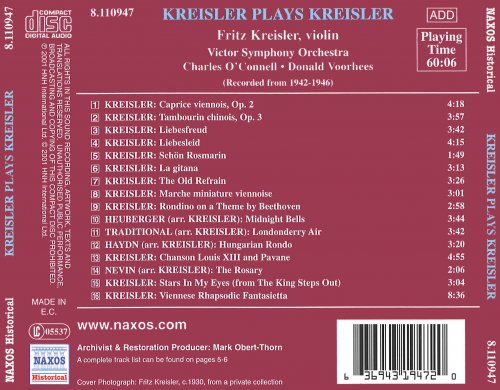

Fritz Kreisler, Victor Symphony Orchestra, Charles O'Connell - Kreisler Plays Kreisler (1942-1946) (2001)

BAND/ARTIST: Fritz Kreisler, Victor Symphony Orchestra, Charles O'Connell

- Title: Kreisler Plays Kreisler

- Year Of Release: 2001

- Label: Naxos

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:00:47

- Total Size: 176 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Caprice viennois, Op. 2 (Arr. I. Bogár for orchestra)

02. Tambourin chinois, Op. 3

03. Liebesfreud

04. Liebesleid

05. Schon Rosmarin (Arr. For violin and orchestra)

06. La gitana

07. The Old Refrain

08. Marche miniature viennoise

09. Rondino on a Theme by Beethoven

10. Midnight Bells [arr. F. Kreisler for violin and orchestra]

11. Londonderry Air

12. Hungarian Rondo (Arr. F. Kreisler for violin and orchestra)

13. Chanson Louis XIII and payane

14. The Rosary (Arr. F. Kreisler)

15. Stars In My Eyes (from the King Steps Out)

16. Viennse Rhapsodie Fantasietta

The years from 1935 to 1955 marked an unhappy period for lovers of great string-playing. Quite apart from the terrible events associated with the Second World War, they saw the untimely deaths of Franz von Vecsey, Mikhail Erdenko, Jan Kubelík, Alphonse Onnou, Miron Polyakin, Emanuel Feuermann, Josef Hassid, Eda Kersey, Ginette Neveu, Bronislaw Huberman, Georg Kulenkampff, Robert Maas, Alfred Dubois, Adolf Busch, Albert Spalding, Ossy Renardy and Jacques Thibaud; the eclipse of Guila Bustabo; and the premature retirements of Karl Klingler, Lionel Tertis, Albert Sammons and Pablo Casals. Along the way there were serious mishaps to Huberman, Busch and the subject of the present release, Fritz Kreisler. In fact the great career of Kreisler was more or less ended in 1941, when he was hit by a van while absent-mindedly crossing a New York street. He was in a coma for four weeks, and although he recovered and did not stop playing in public until after the 1949/50 season, he was never the same again. We are fortunate that RCA Victor captured him in these autumnal performances. Even then, fate had another blow in store, as a dispute between the musicians’ union and the record companies led to a two-year ban on studio recording. So we have Kreisler records from 1942, 1945 and 1946 but nothing from 1943 or 1944. We must be grateful for what we have, as it is bounteous enough.

Friedrich ‘Fritz’ Kreisler was born in Vienna on 2nd February 1875, the son of Sigmund Freud’s family doctor, and could read music when he was three. His first violin lessons came from his Polish father Salomon, an enthusiastic amateur, and he went on to study with Jacques Auber, leader of the Ringtheater orchestra. In 1882 he became the youngest student admitted to the Vienna Conservatory, where his violin tutor was the younger Josef Hellmesberger, and made his début at Carlsbad, now Karlovy Vary, with the singer Carlotta Patti, sister of Adelina. At ten he won the Conservatory gold medal, was given a three-quarter-size Amati by friends and transferred to the Paris Conservatoire, where he studied the with Joseph Massart and composition with Léo Delibes. He met César Franck, played in the Pasdeloup Orchestra and in 1887 took a first prize in violin. In 1888/9 he toured America with the pianist Moriz Rosenthal. He spent two years in Vienna, broadening his education, thought of following his father’s profession and spent two years in medical training, before doing his military service. In 1896 he decided on music and began his career as a travelling virtuoso. He toured Russia, met Glazunov, found a wealthy sponsor and gradually advanced himself, getting to know Joachim, Wolf and Schoenberg as well as Brahms. In January 1898 he made his concerto début in Vienna with Bruch’s Concerto in G minor, conducted by Hans Richter, and a year later he had an even greater success when he played Bruch’s Concerto in D minor, the Concerto in F minor of Vieuxtemps and Paganini’s ‘Non più mesta’ Variations for his début with the Berlin Philharmonic under Josef Rebicek. In November 1899 he was back in Berlin to play the Mendelssohn Concerto in E minor under Arthur Nikisch. In 1900 he toured America and in 1902 he appeared in London, playing the Beethoven Concerto at the first of Richter’s three concerts and the Bruch Concerto in G minor at the third. His marriage to Harriet Lies that year was crucial to his career, as she organized and motivated him from then on. In 1904 he was awarded the Philharmonic Society gold medal, in 1911 he gave the first performance of Elgar’s Violin Concerto and by World War I, in which he was conscripted, wounded in the leg and reported killed, he was famous. He moved to the United States, giving generously to help war orphans and refugees and playing charity concerts. When America entered the war, he was sidelined as an enemy alien; the enforced rest resulted in his operetta Apple Blossoms and his String Quartet. From 1924 Kreisler made his home in Berlin but with the rise of Hitler in 1933, he refused to play in Germany any more. His admission in 1935 that many ‘baroque’ pieces in his repertoire were his own compositions caused a public rumpus, as the English critic Ernest Newman took umbrage. After the Anschluss of Austria in 1938, Kreisler took French citizenship, then moved to the United States, becoming a citizen in 1943. He died in New York on 29th January 1962.

Part of Kreisler’s special quality stemmed from his hands. ‘He had soft pads on his fingertips, which appeared to be unique,’ recalled the Australian violinist Daisy Kennedy. He developed the silvery vibrato of the Franco-Belgian players such as Ysaÿe and Massart into a warm, sensuous vibrato that he applied to every phrase, virtually overlapping it from note to note. This way of ‘keeping the left hand alive’ was a revelation to his rivals and admirers alike, at the turn of the century. One admirer was Lionel Tertis, who adapted the Kreisler vibrato to the viola; Pablo Casals was already working on similar lines to create a new cello sound – and thus, within a decade or so, the entire approach to playing stringed instruments began to change. Another Kreisler speciality was extracting different colours from the violin, by playing particular notes in unusual positions, an ability he used to create the most delicate effects in short pieces such as those included here. In these delicious trifles he demonstrated his natural command of tempo rubato, fine intonation – his double stops were legendary – and economical bowing. He kept the bow hair exceptionally tight, not even loosening it between performances, and varied the pressure; at one moment the bow seemed glued to the string, at another it moved with the deftness he had learnt in Paris.

Nowadays we use the word ‘album’ to mean a recorded collection of songs or tunes. In the days of heavy shellac 78rpm discs, an album was exactly what the word implies, a big book in which each ‘page’ was a thick envelope, into which a record could be slid. A hole in the middle of each side of the envelope allowed you to read the disc label. The first albums were produced by the record companies to house works such as symphonies or operas which took up a number of discs; but by the time Kreisler made these recordings, it was realised that a collection of performances by a single artist could be sold in this way. The 1940s saw albums of all sorts of popular fare, such as Broadway musicals. For violin fanciers, apart from the two albums which held most of these Kreisler treats, there were such excitements as an album of Brahms Hungarian Dances by Erica Morini and two albums of Paganini Caprices by Ossy Renardy. Kreisler’s 1942 recordings, with Philadelphia Orchestra members masquerading as the Victor Symphony Orchestra, were issued in an album entitled My Favorites. Kreisler had made earlier records of all the pieces with piano accompaniment, but these versions, for which he wrote special orchestral arrangements, were often more relaxed in mood. For the 1945 sessions, he produced two novelties, his own Marche miniature viennoise, which he had recorded only once before, in Berlin in 1927, and an arrangement of the Gipsy Rondo from Haydn’s Piano Trio in G major, Hob.XV: 25, which he had not previously recorded. Likewise, for his last studio session he came up with two pieces new to his discography, Stars in My Eyes and the Viennese Rhapsodic Fantasietta. In all these recordings his fabled tone and subtle rhythmic sense were still much in evidence.

01. Caprice viennois, Op. 2 (Arr. I. Bogár for orchestra)

02. Tambourin chinois, Op. 3

03. Liebesfreud

04. Liebesleid

05. Schon Rosmarin (Arr. For violin and orchestra)

06. La gitana

07. The Old Refrain

08. Marche miniature viennoise

09. Rondino on a Theme by Beethoven

10. Midnight Bells [arr. F. Kreisler for violin and orchestra]

11. Londonderry Air

12. Hungarian Rondo (Arr. F. Kreisler for violin and orchestra)

13. Chanson Louis XIII and payane

14. The Rosary (Arr. F. Kreisler)

15. Stars In My Eyes (from the King Steps Out)

16. Viennse Rhapsodie Fantasietta

The years from 1935 to 1955 marked an unhappy period for lovers of great string-playing. Quite apart from the terrible events associated with the Second World War, they saw the untimely deaths of Franz von Vecsey, Mikhail Erdenko, Jan Kubelík, Alphonse Onnou, Miron Polyakin, Emanuel Feuermann, Josef Hassid, Eda Kersey, Ginette Neveu, Bronislaw Huberman, Georg Kulenkampff, Robert Maas, Alfred Dubois, Adolf Busch, Albert Spalding, Ossy Renardy and Jacques Thibaud; the eclipse of Guila Bustabo; and the premature retirements of Karl Klingler, Lionel Tertis, Albert Sammons and Pablo Casals. Along the way there were serious mishaps to Huberman, Busch and the subject of the present release, Fritz Kreisler. In fact the great career of Kreisler was more or less ended in 1941, when he was hit by a van while absent-mindedly crossing a New York street. He was in a coma for four weeks, and although he recovered and did not stop playing in public until after the 1949/50 season, he was never the same again. We are fortunate that RCA Victor captured him in these autumnal performances. Even then, fate had another blow in store, as a dispute between the musicians’ union and the record companies led to a two-year ban on studio recording. So we have Kreisler records from 1942, 1945 and 1946 but nothing from 1943 or 1944. We must be grateful for what we have, as it is bounteous enough.

Friedrich ‘Fritz’ Kreisler was born in Vienna on 2nd February 1875, the son of Sigmund Freud’s family doctor, and could read music when he was three. His first violin lessons came from his Polish father Salomon, an enthusiastic amateur, and he went on to study with Jacques Auber, leader of the Ringtheater orchestra. In 1882 he became the youngest student admitted to the Vienna Conservatory, where his violin tutor was the younger Josef Hellmesberger, and made his début at Carlsbad, now Karlovy Vary, with the singer Carlotta Patti, sister of Adelina. At ten he won the Conservatory gold medal, was given a three-quarter-size Amati by friends and transferred to the Paris Conservatoire, where he studied the with Joseph Massart and composition with Léo Delibes. He met César Franck, played in the Pasdeloup Orchestra and in 1887 took a first prize in violin. In 1888/9 he toured America with the pianist Moriz Rosenthal. He spent two years in Vienna, broadening his education, thought of following his father’s profession and spent two years in medical training, before doing his military service. In 1896 he decided on music and began his career as a travelling virtuoso. He toured Russia, met Glazunov, found a wealthy sponsor and gradually advanced himself, getting to know Joachim, Wolf and Schoenberg as well as Brahms. In January 1898 he made his concerto début in Vienna with Bruch’s Concerto in G minor, conducted by Hans Richter, and a year later he had an even greater success when he played Bruch’s Concerto in D minor, the Concerto in F minor of Vieuxtemps and Paganini’s ‘Non più mesta’ Variations for his début with the Berlin Philharmonic under Josef Rebicek. In November 1899 he was back in Berlin to play the Mendelssohn Concerto in E minor under Arthur Nikisch. In 1900 he toured America and in 1902 he appeared in London, playing the Beethoven Concerto at the first of Richter’s three concerts and the Bruch Concerto in G minor at the third. His marriage to Harriet Lies that year was crucial to his career, as she organized and motivated him from then on. In 1904 he was awarded the Philharmonic Society gold medal, in 1911 he gave the first performance of Elgar’s Violin Concerto and by World War I, in which he was conscripted, wounded in the leg and reported killed, he was famous. He moved to the United States, giving generously to help war orphans and refugees and playing charity concerts. When America entered the war, he was sidelined as an enemy alien; the enforced rest resulted in his operetta Apple Blossoms and his String Quartet. From 1924 Kreisler made his home in Berlin but with the rise of Hitler in 1933, he refused to play in Germany any more. His admission in 1935 that many ‘baroque’ pieces in his repertoire were his own compositions caused a public rumpus, as the English critic Ernest Newman took umbrage. After the Anschluss of Austria in 1938, Kreisler took French citizenship, then moved to the United States, becoming a citizen in 1943. He died in New York on 29th January 1962.

Part of Kreisler’s special quality stemmed from his hands. ‘He had soft pads on his fingertips, which appeared to be unique,’ recalled the Australian violinist Daisy Kennedy. He developed the silvery vibrato of the Franco-Belgian players such as Ysaÿe and Massart into a warm, sensuous vibrato that he applied to every phrase, virtually overlapping it from note to note. This way of ‘keeping the left hand alive’ was a revelation to his rivals and admirers alike, at the turn of the century. One admirer was Lionel Tertis, who adapted the Kreisler vibrato to the viola; Pablo Casals was already working on similar lines to create a new cello sound – and thus, within a decade or so, the entire approach to playing stringed instruments began to change. Another Kreisler speciality was extracting different colours from the violin, by playing particular notes in unusual positions, an ability he used to create the most delicate effects in short pieces such as those included here. In these delicious trifles he demonstrated his natural command of tempo rubato, fine intonation – his double stops were legendary – and economical bowing. He kept the bow hair exceptionally tight, not even loosening it between performances, and varied the pressure; at one moment the bow seemed glued to the string, at another it moved with the deftness he had learnt in Paris.

Nowadays we use the word ‘album’ to mean a recorded collection of songs or tunes. In the days of heavy shellac 78rpm discs, an album was exactly what the word implies, a big book in which each ‘page’ was a thick envelope, into which a record could be slid. A hole in the middle of each side of the envelope allowed you to read the disc label. The first albums were produced by the record companies to house works such as symphonies or operas which took up a number of discs; but by the time Kreisler made these recordings, it was realised that a collection of performances by a single artist could be sold in this way. The 1940s saw albums of all sorts of popular fare, such as Broadway musicals. For violin fanciers, apart from the two albums which held most of these Kreisler treats, there were such excitements as an album of Brahms Hungarian Dances by Erica Morini and two albums of Paganini Caprices by Ossy Renardy. Kreisler’s 1942 recordings, with Philadelphia Orchestra members masquerading as the Victor Symphony Orchestra, were issued in an album entitled My Favorites. Kreisler had made earlier records of all the pieces with piano accompaniment, but these versions, for which he wrote special orchestral arrangements, were often more relaxed in mood. For the 1945 sessions, he produced two novelties, his own Marche miniature viennoise, which he had recorded only once before, in Berlin in 1927, and an arrangement of the Gipsy Rondo from Haydn’s Piano Trio in G major, Hob.XV: 25, which he had not previously recorded. Likewise, for his last studio session he came up with two pieces new to his discography, Stars in My Eyes and the Viennese Rhapsodic Fantasietta. In all these recordings his fabled tone and subtle rhythmic sense were still much in evidence.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads