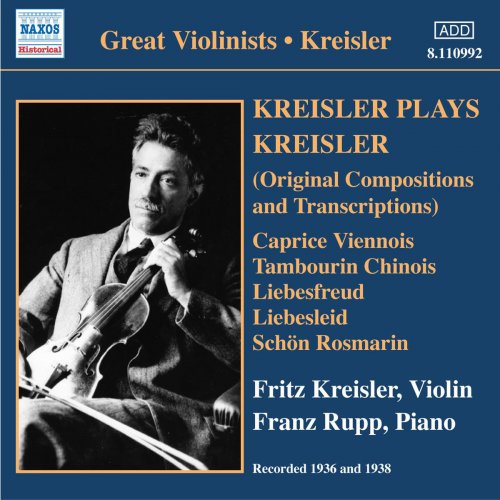

Fritz Kreisler, Franz Rupp - Kreisler plays Kreisler (2005)

BAND/ARTIST: Fritz Kreisler, Franz Rupp

- Title: Kreisler plays Kreisler

- Year Of Release: 2005

- Label: Naxos

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:07:06

- Total Size: 262 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

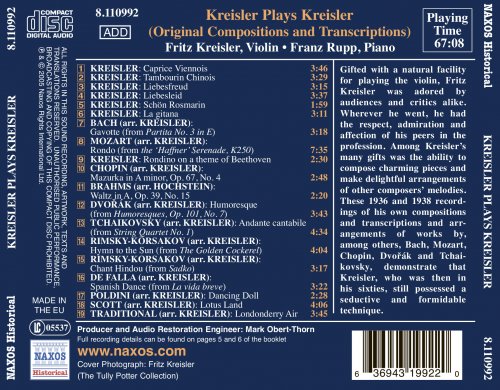

01. Caprice Viennois, Op. 2

02. Tambourin chinois, Op. 3

03. Liebesfreud

04. Liebesleid

05. Schon Rosmarin

06. La gitana

07. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006 III. Gavotte (arr. F. Kreisler)

08. Serenade No. 7 in D Major, K. 250, Haffner IV. Rondo (arr. F. Kreisler)

09. Rondino on a Theme by Beethoven

10. Mazurka in A Minor, Op. 67, No. 4 (arr. F. Kreisler)

11. Waltz in A-Flat Major, Op. 39, No. 15 (arr. D. Hochstein)

12. 8 Humoresques, Op. 101, B. 187 No. 7. Poco lento e grazioso in G-Flat Major (arr. F. Kreisler)

13. String Quartet No. 1 in D Major, Op. 11 II. Andante cantabile (arr. F. Kreisler)

14. Le Coq d’Or (The Golden Cockerel), Act II Hymn to the Sun (arr. F. Kreisler)

15. Sadko Song of the Indian Guest (Chant hindou) (arr. F. Kreisler)

16. La vida breve, Act II Danse espagnole No. 1 (arr. F. Kreisler)

17. Poupee valsante (Dancing Doll) (arr. F. Kreisler)

18. Lotus Land, Op. 47, No. 1 (arr. F. Kreisler)

19. Londonderry Air (arr. F. Kreisler for violin and piano)

In a magazine article, Fritz Kreisler happily acknowledged that he had been born under a lucky star. Fortune smiled on him and even set-backs seemed to work out to his advantage. Gifted with a natural facility for playing the violin, he did not need to practise or rehearse as much as most of his colleagues. Critics and audiences loved him, wherever he went, and he had the respect, admiration and affection of his peers in the profession. He also played the piano and created an exquisite tone on it, to the despair of his pianist friends. ‘He had that sound in his head’, said his accompanist Franz Rupp, ‘and could bring it out of every instrument’. Rupp once heard Kreisler play an inexpensive violin in a Swedish shop and draw from it exactly the same tone that he produced on his Guarnerius. A highly intelligent man, capable of holding his own in any company, Kreisler had the common touch, so that people in all walks of life enjoyed meeting him. He appeared to bear a charmed existence – wounded and reported dead during active service in the Great War, he was not permanently incapacitated. Even the coming of the Nazis to Germany and his native Austria hardly disturbed the serene progress of his career; and he was in his midsixties by the time his luck finally ran out, with his serious accident in New York. Even then he lived to enjoy an honoured old age. Among Kreisler’s many gifts was the ability to compose charming pieces and make delightful arrangements of other composers’ melodies. And no one played such sweetmeats as easily, stylishly and winningly as he did. This disc concentrates on that side of the great violinist’s art.

Born Friedrich Kreisler in Vienna on 2nd February 1875, he could read music when he was three. His first violin lessons came from his Polish physician father Salomon, an enthusiastic amateur, and he went on to Jacques Auber, leader of the Ringtheater orchestra. In 1882 he became the youngest student admitted to the Vienna Conservatory (where his violin tutor was Josef Hellmesberger Jnr and his composition tutor Anton Bruckner) and made his début at Carlsbad (now Karlovy Vary) with the singer Carlotta Patti, sister of Adelina. At ten he won the Conservatory gold medal, was given a three-quarter-size Amati by friends and transferred to the Paris Conservatoire (studying violin with Joseph Massart, composition with Leo Delibes). He met César Franck, played in the Pasdeloup Orchestra and in 1887 took a first prize in violin. In 1888-89 he toured America with the Polish pianist Moriz Rosenthal. He spent two years back in Vienna, broadening his education, thought of following his father’s profession and completed two years’ medical training, then did his military service. In 1896 he opted for music and, after being refused a job in the Court Opera Orchestra by the concertmaster Arnold Rosé, began his career as a virtuoso. He toured Russia, met Glazunov, found a wealthy sponsor and gradually advanced himself, getting to know Joseph Joachim, Hugo Wolf and Arnold Schoenberg as well as Brahms. In January 1898 he made his concerto début in Vienna with Bruch’s Concerto in G minor, conducted by Hans Richter, and in March 1899 he had an even greater triumph when he played Bruch’s D minor Concerto, Vieuxtemps’ Concerto in F sharp minor and Paganini’s ‘Non più mesta’ Variations for his Berlin Philharmonic début under Josef Rebicek. In November 1899 he was back in Berlin to play Mendelssohn’s E minor Concerto under Arthur Nikisch. In 1900 he toured America and in 1902 he appeared in London, playing the Beethoven Concerto at the first of Richter’s concerts, on 12th May, and the Bruch G minor at the third. That year he married Harriet Lies. In 1904 he began his recording career and received the Philharmonic Society gold medal, in 1910 he toured Russia again, in 1911 he gave the première of Elgar’s Concerto and by World War I, in which he was conscripted, wounded and discharged with the rank of captain, he was known all over the world. He moved to the United States, giving generously to help war orphans and refugees and playing charity concerts. When America entered the war, he was sidelined as an enemy alien, writing his operetta Apple Blossoms and his String Quartet. From 1924 Kreisler made his home in Berlin but spent much time in America and from the late 1920s sometimes appeared in concert with Sergey Rachmaninov. The two of them made recordings together. In 1932 his second operetta, Sissy, was successfully premièred in Vienna. With the rise of Hitler in 1933, he refused to play in Germany any more because of the treatment of his fellow Jews. When he admitted in 1935 that many of the ‘baroque’ pieces in his repertoire were his own compositions, he caused an international scandal – the English critic Ernest Newman was particularly outspoken. Among Kreisler’s colleagues, Mischa Elman was upset, but Albert Spalding, George Enescu, Adolf Busch, Jascha Heifetz and Efrem Zimbalist took it in their stride. After the Anschluss of Austria by Hitler in 1938, Kreisler became a French citizen, then emigrated permanently to the United States, taking citizenship in 1943. His career was more or less ended in 1941, when he was hit by a van while absentmindedly crossing a New York street. He was in a coma for four weeks, and although he recovered and did not stop playing in public until after the 1949-50 season, he was never quite the same again. He died in New York on 29th January 1962.

Part of Kreisler’s quality as a fiddler stemmed from his hands. ‘He had soft pads on his fingertips, which appeared to be unique’, the Australian violinist Daisy Kennedy recalled. He developed the silvery vibrations of Franco-Belgian players such as Ysaÿe and Massart into a warm, sensuous, continuous vibrato, virtually overlapping it from note to note. It was a revelation to his fellow string players: Lionel Tertis adapted it to the viola and Pablo Casals worked on similar lines to create a new cello sound, so that within a decade or so the revolution spread to the orchestras. Another Kreisler speciality was extracting different colours from the violin, by playing notes in unusual positions – an ability he used especially in pieces such as those on this disc. In these trifles he demonstrated his glowing tone, natural rubato, fine intonation – his double stops were legendary – and economical bowing. He kept the bow hair very tight (not even loosening it between performances) and varied the pressure: at one moment the bow seemed glued to the string, at another it moved with the deftness he had learnt in Paris.

In the first half of the last century, hardly a musicloving, middle-class household in Europe or America did not possess at least one Kreisler 78rpm record, and as often as not, it would contain two of his encores. His record companies HMV (who covered Europe) and Victor (who sold to the Americas) recorded him in his most popular pieces several times over, as their techniques improved. The most dramatic change came when electrical recording with a microphone was introduced in 1925, and Kreisler obliged with a whole string of popular discs. By the 1930s, however, HMV in particular had brought the craft of recording to a new peak, and so Kreisler’s ‘greatest hits’ were in demand again. When these sessions were held he was in his sixties, a time of life when, in those days, string players were past their best. Kreisler was an exception and, while it would be silly to claim that his technique was quite what it had been ten years earlier, any tiny lapse in tuning was offset by even greater guile and the vividness of the new records. Of the pieces here Caprice viennois, Tambourin chinois, La gitana and Rondino on a Theme of Beethoven are Kreisler compositions. Liebesfreud (Love’s Joy), Liebesleid (Love’s Sorrow) and Schön Rosmarin are original, but published as ‘Old Viennese Dance Tunes’. Londonderry Air and the Bach, Mozart, Chopin, Dvofiák, Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Falla, Poldini and Scott are arrangements or transcriptions. The beautiful version of the Brahms waltz is the odd one out: it is all (apart from a few dim recordings including this very piece) that we have from the brilliant young American violinist David Hochstein, who was killed in the Great War. Kreisler felt he could not improve on Hochstein’s transcription and so recorded this tribute to a younger colleague.

01. Caprice Viennois, Op. 2

02. Tambourin chinois, Op. 3

03. Liebesfreud

04. Liebesleid

05. Schon Rosmarin

06. La gitana

07. Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006 III. Gavotte (arr. F. Kreisler)

08. Serenade No. 7 in D Major, K. 250, Haffner IV. Rondo (arr. F. Kreisler)

09. Rondino on a Theme by Beethoven

10. Mazurka in A Minor, Op. 67, No. 4 (arr. F. Kreisler)

11. Waltz in A-Flat Major, Op. 39, No. 15 (arr. D. Hochstein)

12. 8 Humoresques, Op. 101, B. 187 No. 7. Poco lento e grazioso in G-Flat Major (arr. F. Kreisler)

13. String Quartet No. 1 in D Major, Op. 11 II. Andante cantabile (arr. F. Kreisler)

14. Le Coq d’Or (The Golden Cockerel), Act II Hymn to the Sun (arr. F. Kreisler)

15. Sadko Song of the Indian Guest (Chant hindou) (arr. F. Kreisler)

16. La vida breve, Act II Danse espagnole No. 1 (arr. F. Kreisler)

17. Poupee valsante (Dancing Doll) (arr. F. Kreisler)

18. Lotus Land, Op. 47, No. 1 (arr. F. Kreisler)

19. Londonderry Air (arr. F. Kreisler for violin and piano)

In a magazine article, Fritz Kreisler happily acknowledged that he had been born under a lucky star. Fortune smiled on him and even set-backs seemed to work out to his advantage. Gifted with a natural facility for playing the violin, he did not need to practise or rehearse as much as most of his colleagues. Critics and audiences loved him, wherever he went, and he had the respect, admiration and affection of his peers in the profession. He also played the piano and created an exquisite tone on it, to the despair of his pianist friends. ‘He had that sound in his head’, said his accompanist Franz Rupp, ‘and could bring it out of every instrument’. Rupp once heard Kreisler play an inexpensive violin in a Swedish shop and draw from it exactly the same tone that he produced on his Guarnerius. A highly intelligent man, capable of holding his own in any company, Kreisler had the common touch, so that people in all walks of life enjoyed meeting him. He appeared to bear a charmed existence – wounded and reported dead during active service in the Great War, he was not permanently incapacitated. Even the coming of the Nazis to Germany and his native Austria hardly disturbed the serene progress of his career; and he was in his midsixties by the time his luck finally ran out, with his serious accident in New York. Even then he lived to enjoy an honoured old age. Among Kreisler’s many gifts was the ability to compose charming pieces and make delightful arrangements of other composers’ melodies. And no one played such sweetmeats as easily, stylishly and winningly as he did. This disc concentrates on that side of the great violinist’s art.

Born Friedrich Kreisler in Vienna on 2nd February 1875, he could read music when he was three. His first violin lessons came from his Polish physician father Salomon, an enthusiastic amateur, and he went on to Jacques Auber, leader of the Ringtheater orchestra. In 1882 he became the youngest student admitted to the Vienna Conservatory (where his violin tutor was Josef Hellmesberger Jnr and his composition tutor Anton Bruckner) and made his début at Carlsbad (now Karlovy Vary) with the singer Carlotta Patti, sister of Adelina. At ten he won the Conservatory gold medal, was given a three-quarter-size Amati by friends and transferred to the Paris Conservatoire (studying violin with Joseph Massart, composition with Leo Delibes). He met César Franck, played in the Pasdeloup Orchestra and in 1887 took a first prize in violin. In 1888-89 he toured America with the Polish pianist Moriz Rosenthal. He spent two years back in Vienna, broadening his education, thought of following his father’s profession and completed two years’ medical training, then did his military service. In 1896 he opted for music and, after being refused a job in the Court Opera Orchestra by the concertmaster Arnold Rosé, began his career as a virtuoso. He toured Russia, met Glazunov, found a wealthy sponsor and gradually advanced himself, getting to know Joseph Joachim, Hugo Wolf and Arnold Schoenberg as well as Brahms. In January 1898 he made his concerto début in Vienna with Bruch’s Concerto in G minor, conducted by Hans Richter, and in March 1899 he had an even greater triumph when he played Bruch’s D minor Concerto, Vieuxtemps’ Concerto in F sharp minor and Paganini’s ‘Non più mesta’ Variations for his Berlin Philharmonic début under Josef Rebicek. In November 1899 he was back in Berlin to play Mendelssohn’s E minor Concerto under Arthur Nikisch. In 1900 he toured America and in 1902 he appeared in London, playing the Beethoven Concerto at the first of Richter’s concerts, on 12th May, and the Bruch G minor at the third. That year he married Harriet Lies. In 1904 he began his recording career and received the Philharmonic Society gold medal, in 1910 he toured Russia again, in 1911 he gave the première of Elgar’s Concerto and by World War I, in which he was conscripted, wounded and discharged with the rank of captain, he was known all over the world. He moved to the United States, giving generously to help war orphans and refugees and playing charity concerts. When America entered the war, he was sidelined as an enemy alien, writing his operetta Apple Blossoms and his String Quartet. From 1924 Kreisler made his home in Berlin but spent much time in America and from the late 1920s sometimes appeared in concert with Sergey Rachmaninov. The two of them made recordings together. In 1932 his second operetta, Sissy, was successfully premièred in Vienna. With the rise of Hitler in 1933, he refused to play in Germany any more because of the treatment of his fellow Jews. When he admitted in 1935 that many of the ‘baroque’ pieces in his repertoire were his own compositions, he caused an international scandal – the English critic Ernest Newman was particularly outspoken. Among Kreisler’s colleagues, Mischa Elman was upset, but Albert Spalding, George Enescu, Adolf Busch, Jascha Heifetz and Efrem Zimbalist took it in their stride. After the Anschluss of Austria by Hitler in 1938, Kreisler became a French citizen, then emigrated permanently to the United States, taking citizenship in 1943. His career was more or less ended in 1941, when he was hit by a van while absentmindedly crossing a New York street. He was in a coma for four weeks, and although he recovered and did not stop playing in public until after the 1949-50 season, he was never quite the same again. He died in New York on 29th January 1962.

Part of Kreisler’s quality as a fiddler stemmed from his hands. ‘He had soft pads on his fingertips, which appeared to be unique’, the Australian violinist Daisy Kennedy recalled. He developed the silvery vibrations of Franco-Belgian players such as Ysaÿe and Massart into a warm, sensuous, continuous vibrato, virtually overlapping it from note to note. It was a revelation to his fellow string players: Lionel Tertis adapted it to the viola and Pablo Casals worked on similar lines to create a new cello sound, so that within a decade or so the revolution spread to the orchestras. Another Kreisler speciality was extracting different colours from the violin, by playing notes in unusual positions – an ability he used especially in pieces such as those on this disc. In these trifles he demonstrated his glowing tone, natural rubato, fine intonation – his double stops were legendary – and economical bowing. He kept the bow hair very tight (not even loosening it between performances) and varied the pressure: at one moment the bow seemed glued to the string, at another it moved with the deftness he had learnt in Paris.

In the first half of the last century, hardly a musicloving, middle-class household in Europe or America did not possess at least one Kreisler 78rpm record, and as often as not, it would contain two of his encores. His record companies HMV (who covered Europe) and Victor (who sold to the Americas) recorded him in his most popular pieces several times over, as their techniques improved. The most dramatic change came when electrical recording with a microphone was introduced in 1925, and Kreisler obliged with a whole string of popular discs. By the 1930s, however, HMV in particular had brought the craft of recording to a new peak, and so Kreisler’s ‘greatest hits’ were in demand again. When these sessions were held he was in his sixties, a time of life when, in those days, string players were past their best. Kreisler was an exception and, while it would be silly to claim that his technique was quite what it had been ten years earlier, any tiny lapse in tuning was offset by even greater guile and the vividness of the new records. Of the pieces here Caprice viennois, Tambourin chinois, La gitana and Rondino on a Theme of Beethoven are Kreisler compositions. Liebesfreud (Love’s Joy), Liebesleid (Love’s Sorrow) and Schön Rosmarin are original, but published as ‘Old Viennese Dance Tunes’. Londonderry Air and the Bach, Mozart, Chopin, Dvofiák, Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Falla, Poldini and Scott are arrangements or transcriptions. The beautiful version of the Brahms waltz is the odd one out: it is all (apart from a few dim recordings including this very piece) that we have from the brilliant young American violinist David Hochstein, who was killed in the Great War. Kreisler felt he could not improve on Hochstein’s transcription and so recorded this tribute to a younger colleague.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads