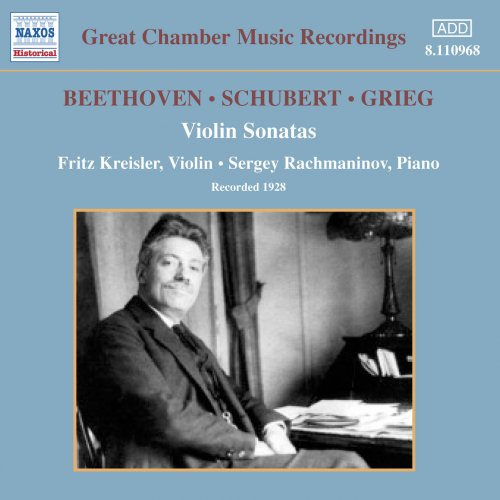

Fritz Kreisler & Sergey Rachmaninov - BEETHOVEN / SCHUBERT / GRIEG: Violin Sonatas (Kreisler / Rachmaninov) (1928) (2003)

BAND/ARTIST: Fritz Kreisler, Sergey Rachmaninov

- Title: BEETHOVEN / SCHUBERT / GRIEG: Violin Sonatas (Kreisler / Rachmaninov) (1928)

- Year Of Release: 2003

- Label: Naxos

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:13:12

- Total Size: 200 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

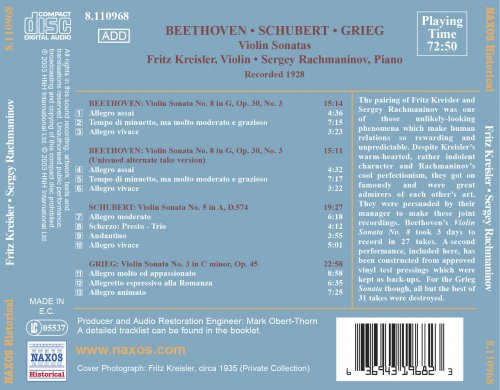

01. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Allegro assai

02. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Tempo di minuetto, ma molto moderato e grazioso

03. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Allegro vivace

04. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Allegro assai

05. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Tempo di minuetto, ma molto moderato e grazioso

06. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Allegro vivace

07. Duo Sonata in A major, Op. 162, D. 574: Allegro moderato

08. Duo Sonata in A major, Op. 162, D. 574: Scherzo. Presto - Trio

09. Duo Sonata in A major, Op. 162, D. 574: Andantino

10. Duo Sonata in A major, Op. 162, D. 574: Allegro vivace

11. O lucidissima dies: Allegro molto ed appassionato

12. O lucidissima dies: Allegretto espressivo alla Romanza

13. O lucidissima dies: Allegro animato

The pairing of Fritz Kreisler and Sergey Rachmaninov was one of those unlikely-looking phenomena which make human relations so rewarding and unpredictable. In theory the warm-hearted, rather indolent Kreisler and the cool perfectionist Rachmaninov should not even have liked each other, let alone have been able to make music together. Yet from all accounts they got on famously and were great admirers of each other’s art. Rachmaninov transcribed Kreisler’s celebrated Viennese-style pieces Liebesfreud and Liebesleid for piano and even recorded them. Kreisler repaid the compliment by transcribing one of Rachmaninov’s songs for violin and recording it, and he also collaborated with the tenor John McCormack on discs of two more Rachmaninov songs. The two men met and became friendly when Rachmaninov went to Vienna in the spring of 1903 to play his new Second Concerto with the Philharmonic under Vasily Safonov. Kreisler happened to be in town, went to the concert and was impressed both by the music and by the composer-pianist’s performance. The two met from time to time as their busy schedules permitted; and when Rachmaninov left Russia for America in the wake of the Revolution, they were thrown together regularly. In 1928 they were persuaded by Charles Foley, who managed both their careers, to make these joint recordings, and although they did not often appear in concert as a duo, Rachmaninov showed his true opinion of Kreisler in 1931 by dedicating his Corelli Variations for piano to the violinist. It is a pity that he did not think of writing a violin sonata for them to play together.

Sergey Rachmaninov was born at Oneg, Novgorod, on 1st April, 1873, into the Russian landed gentry. Both his parents were amateur musicians and he had his first piano lessons from his mother. By 1882 his father had lost the family money and Sergey moved with his mother to St Petersburg, but his indifferent academic performance there led his cousin Ziloti to suggest that he should go to the Moscow Conservatory to study with Nicolay Zverev. This he did, living in Zverev’s house for four years and then with his aunt. He was later to marry his cousin Natalia. At the age of fourteen Rachmaninov was already marked out as a composer and his career prospered until the disastrous première of his First Symphony in 1897. The débacle brought about a creative block but in 1898 he made his London début conducting his fantasy The Rock. With medical help he managed to write his Second Concerto, which ushered in his most productive phase. He became renowned as composer, pianist (mainly in his own music) and conductor, and worked at the Bolshoy from 1904 to 1906. In 1909 he visited the United States, writing the Third Concerto specially for those concerts. From 1911 to 1914 he conducted the Moscow Philharmonic and during the war he toured playing the music of his friend Scriabin, who had died in 1915. At the end of 1917 Rachmaninov emigrated to the United States and worked up a full concert repertoire, so that in the 1920s and 1930s he was regarded as the world’s leading pianist, making a large number of superb records, including many of his own works. From the 1930s he divided his spare time between the United States and Switzerland. He died in Beverly Hills, California, on 28th March, 1943, and for many years was severely underrated as a composer, although his popular works were played. More recently his true stature has been recognised.

Friedrich ‘Fritz’ Kreisler was born in Vienna on 2nd February, 1875, the son of Sigmund Freud’s family physician, and could read music when he was three. His first violin lessons came from his Polish father Salomon and he went on to Jacques Auber. In 1882 he became the youngest student admitted to the Vienna Conservatory, where his violin teacher was the younger Josef Hellmesberger, and made his début at Carlsbad (now Karlovy Vary). At ten he won the Conservatory gold medal, was given a three-quarter-size Amati by friends and transferred to the Paris Conservatoire, studying the violin with Joseph Massart, and composition with Léo Delibes. He met César Franck, played in the Pasdeloup Orchestra and in 1887 took a first prize in violin. In 1888/9 he toured America with the pianist Moriz Rosenthal. He spent two years in Vienna, broadening his education, thought of following his father’s profession and did two years’ medical training, followed by military service. In 1896 he decided on music and began his career as a travelling virtuoso. He toured Russia, met Glazunov, found a sponsor and gradually advanced himself, getting to know Joachim, Wolf and Schoenberg, as well as Brahms. In January 1898 he made his concerto début in Vienna with Bruch’s Concerto in G minor, conducted by Hans Richter, and a year later had an even greater success when he played the same composer’s Concerto in D minor, Vieuxtemps’s Concerto in F sharp minor and Paganini’s ‘Non più mesta’ Variations for his début with the Berlin Philharmonic under Josef Rebicek. In November 1899 he was back in Berlin to play Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor under Arthur Nikisch. In 1900 he toured America and in 1902 he appeared in London, playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto at the first of Richter’s three concerts and the Bruch G minor Concerto at the third. His marriage to Harriet Lies that year was crucial to his career, as she organized and motivated him. In 1904 he was awarded the Philharmonic Society gold medal, in 1911 he gave the first performance of Elgar’s Violin Concerto and by World War I, in which he was conscripted, wounded in the leg and reported killed, he was famous. He moved to the United States, giving generously to help war orphans and refugees and playing charity concerts. When America entered the war, he was sidelined as an enemy alien, and the enforced rest resulted in his operetta Apple Blossoms and his String Quartet. From 1924 Kreisler made his home in Berlin but with the rise of Hitler in 1933, he refused to play in Germany any more. His admission in 1935 that many ‘baroque’ pieces in his repertoire were his own compositions caused a public rumpus, as the English critic Ernest Newman took umbrage. After the Anschluss of Austria in 1938, Kreisler took French citizenship, then moved to the United States, becoming a citizen in 1943. His career was more or less ended in 1941, when he was hit by a van while absent-mindedly crossing a New York street. He was in a coma for four weeks, and although he recovered and did not stop playing in public until after the 1949/50 season, he was never the same again. He died in New York on 29th January, 1962.

Kreisler and Rachmaninov first went into the studio together in Camden on 28th February, 1928, to record Beethoven’s ‘little G major’ Sonata. Four sides were allotted and they did three takes of Sides 1, 2 and 4, as well as two of Side 3. Next day, a leap-year, 29th February, they did three more takes of Sides 1 and 4. Only on the third day of sessions, 22nd March, after 27 takes, did they achieve four sides which were to the obsessive pianist’s liking. A second performance, however, can be constructed from sides which were approved and kept as back-ups. This encore version includes just one take, of Side 2, from the very first session. And so it went on… As Rachmaninov said of the Grieg Sonata, the only one recorded in Berlin: ‘Do the critics who have praised those Grieg records so highly realise the immense amount of hard work and patience necessary to achieve such results? The six sides of the Grieg set we recorded no fewer than five times each. From these thirty discs we finally selected the best, destroying the remainder. Perhaps so much labour did not altogether please Fritz Kreisler. He is a great artist, but does not care to work too hard. Being an optimist, he will declare with enthusiasm that the first set of proofs we make are wonderful, marvellous. But my own pessimism invariably causes me to feel, and argue, that they could be better. So when we work together, Fritz and I, we are always fighting.’ In truth Rachmaninov forgot one take — there were 31. And before we convict Kreisler of laziness, we should note that he began all except one of the American sessions by recording short pieces with his accompanist Carl Lamson. The Schubert Sonata, the last to be recorded, took a mere 26 takes for the six sides and two of the published takes were achieved on the first day.

01. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Allegro assai

02. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Tempo di minuetto, ma molto moderato e grazioso

03. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Allegro vivace

04. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Allegro assai

05. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Tempo di minuetto, ma molto moderato e grazioso

06. Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major, Op. 30 No. 3: Allegro vivace

07. Duo Sonata in A major, Op. 162, D. 574: Allegro moderato

08. Duo Sonata in A major, Op. 162, D. 574: Scherzo. Presto - Trio

09. Duo Sonata in A major, Op. 162, D. 574: Andantino

10. Duo Sonata in A major, Op. 162, D. 574: Allegro vivace

11. O lucidissima dies: Allegro molto ed appassionato

12. O lucidissima dies: Allegretto espressivo alla Romanza

13. O lucidissima dies: Allegro animato

The pairing of Fritz Kreisler and Sergey Rachmaninov was one of those unlikely-looking phenomena which make human relations so rewarding and unpredictable. In theory the warm-hearted, rather indolent Kreisler and the cool perfectionist Rachmaninov should not even have liked each other, let alone have been able to make music together. Yet from all accounts they got on famously and were great admirers of each other’s art. Rachmaninov transcribed Kreisler’s celebrated Viennese-style pieces Liebesfreud and Liebesleid for piano and even recorded them. Kreisler repaid the compliment by transcribing one of Rachmaninov’s songs for violin and recording it, and he also collaborated with the tenor John McCormack on discs of two more Rachmaninov songs. The two men met and became friendly when Rachmaninov went to Vienna in the spring of 1903 to play his new Second Concerto with the Philharmonic under Vasily Safonov. Kreisler happened to be in town, went to the concert and was impressed both by the music and by the composer-pianist’s performance. The two met from time to time as their busy schedules permitted; and when Rachmaninov left Russia for America in the wake of the Revolution, they were thrown together regularly. In 1928 they were persuaded by Charles Foley, who managed both their careers, to make these joint recordings, and although they did not often appear in concert as a duo, Rachmaninov showed his true opinion of Kreisler in 1931 by dedicating his Corelli Variations for piano to the violinist. It is a pity that he did not think of writing a violin sonata for them to play together.

Sergey Rachmaninov was born at Oneg, Novgorod, on 1st April, 1873, into the Russian landed gentry. Both his parents were amateur musicians and he had his first piano lessons from his mother. By 1882 his father had lost the family money and Sergey moved with his mother to St Petersburg, but his indifferent academic performance there led his cousin Ziloti to suggest that he should go to the Moscow Conservatory to study with Nicolay Zverev. This he did, living in Zverev’s house for four years and then with his aunt. He was later to marry his cousin Natalia. At the age of fourteen Rachmaninov was already marked out as a composer and his career prospered until the disastrous première of his First Symphony in 1897. The débacle brought about a creative block but in 1898 he made his London début conducting his fantasy The Rock. With medical help he managed to write his Second Concerto, which ushered in his most productive phase. He became renowned as composer, pianist (mainly in his own music) and conductor, and worked at the Bolshoy from 1904 to 1906. In 1909 he visited the United States, writing the Third Concerto specially for those concerts. From 1911 to 1914 he conducted the Moscow Philharmonic and during the war he toured playing the music of his friend Scriabin, who had died in 1915. At the end of 1917 Rachmaninov emigrated to the United States and worked up a full concert repertoire, so that in the 1920s and 1930s he was regarded as the world’s leading pianist, making a large number of superb records, including many of his own works. From the 1930s he divided his spare time between the United States and Switzerland. He died in Beverly Hills, California, on 28th March, 1943, and for many years was severely underrated as a composer, although his popular works were played. More recently his true stature has been recognised.

Friedrich ‘Fritz’ Kreisler was born in Vienna on 2nd February, 1875, the son of Sigmund Freud’s family physician, and could read music when he was three. His first violin lessons came from his Polish father Salomon and he went on to Jacques Auber. In 1882 he became the youngest student admitted to the Vienna Conservatory, where his violin teacher was the younger Josef Hellmesberger, and made his début at Carlsbad (now Karlovy Vary). At ten he won the Conservatory gold medal, was given a three-quarter-size Amati by friends and transferred to the Paris Conservatoire, studying the violin with Joseph Massart, and composition with Léo Delibes. He met César Franck, played in the Pasdeloup Orchestra and in 1887 took a first prize in violin. In 1888/9 he toured America with the pianist Moriz Rosenthal. He spent two years in Vienna, broadening his education, thought of following his father’s profession and did two years’ medical training, followed by military service. In 1896 he decided on music and began his career as a travelling virtuoso. He toured Russia, met Glazunov, found a sponsor and gradually advanced himself, getting to know Joachim, Wolf and Schoenberg, as well as Brahms. In January 1898 he made his concerto début in Vienna with Bruch’s Concerto in G minor, conducted by Hans Richter, and a year later had an even greater success when he played the same composer’s Concerto in D minor, Vieuxtemps’s Concerto in F sharp minor and Paganini’s ‘Non più mesta’ Variations for his début with the Berlin Philharmonic under Josef Rebicek. In November 1899 he was back in Berlin to play Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor under Arthur Nikisch. In 1900 he toured America and in 1902 he appeared in London, playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto at the first of Richter’s three concerts and the Bruch G minor Concerto at the third. His marriage to Harriet Lies that year was crucial to his career, as she organized and motivated him. In 1904 he was awarded the Philharmonic Society gold medal, in 1911 he gave the first performance of Elgar’s Violin Concerto and by World War I, in which he was conscripted, wounded in the leg and reported killed, he was famous. He moved to the United States, giving generously to help war orphans and refugees and playing charity concerts. When America entered the war, he was sidelined as an enemy alien, and the enforced rest resulted in his operetta Apple Blossoms and his String Quartet. From 1924 Kreisler made his home in Berlin but with the rise of Hitler in 1933, he refused to play in Germany any more. His admission in 1935 that many ‘baroque’ pieces in his repertoire were his own compositions caused a public rumpus, as the English critic Ernest Newman took umbrage. After the Anschluss of Austria in 1938, Kreisler took French citizenship, then moved to the United States, becoming a citizen in 1943. His career was more or less ended in 1941, when he was hit by a van while absent-mindedly crossing a New York street. He was in a coma for four weeks, and although he recovered and did not stop playing in public until after the 1949/50 season, he was never the same again. He died in New York on 29th January, 1962.

Kreisler and Rachmaninov first went into the studio together in Camden on 28th February, 1928, to record Beethoven’s ‘little G major’ Sonata. Four sides were allotted and they did three takes of Sides 1, 2 and 4, as well as two of Side 3. Next day, a leap-year, 29th February, they did three more takes of Sides 1 and 4. Only on the third day of sessions, 22nd March, after 27 takes, did they achieve four sides which were to the obsessive pianist’s liking. A second performance, however, can be constructed from sides which were approved and kept as back-ups. This encore version includes just one take, of Side 2, from the very first session. And so it went on… As Rachmaninov said of the Grieg Sonata, the only one recorded in Berlin: ‘Do the critics who have praised those Grieg records so highly realise the immense amount of hard work and patience necessary to achieve such results? The six sides of the Grieg set we recorded no fewer than five times each. From these thirty discs we finally selected the best, destroying the remainder. Perhaps so much labour did not altogether please Fritz Kreisler. He is a great artist, but does not care to work too hard. Being an optimist, he will declare with enthusiasm that the first set of proofs we make are wonderful, marvellous. But my own pessimism invariably causes me to feel, and argue, that they could be better. So when we work together, Fritz and I, we are always fighting.’ In truth Rachmaninov forgot one take — there were 31. And before we convict Kreisler of laziness, we should note that he began all except one of the American sessions by recording short pieces with his accompanist Carl Lamson. The Schubert Sonata, the last to be recorded, took a mere 26 takes for the six sides and two of the published takes were achieved on the first day.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads