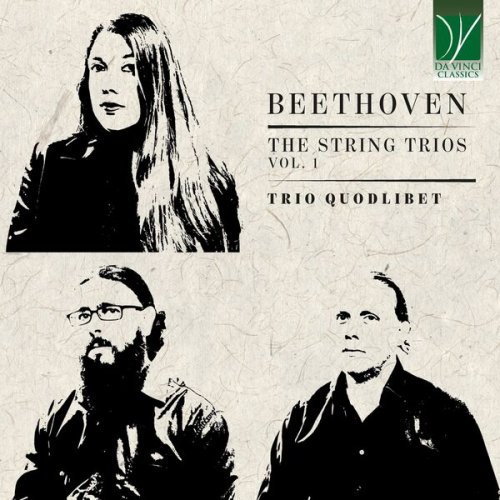

Trio Quodlibet - Ludwig van Beethoven: The String Trios, Vol. 1 (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Trio Quodlibet

- Title: Ludwig van Beethoven: The String Trios, Vol. 1

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:09:37

- Total Size: 275 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: I. Allegro con brio

02. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: II. Andante

03. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: III. Minuet. Allegretto

04. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: IV. Adagio

05. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: V. Minuet. Moderato

06. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: VI. Finale. Allegro

07. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: I. Marcia. Allegro

08. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: I. Adagio

09. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: II. Minuet. Allegretto

10. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: III. Adagio

11. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: IV. Allegretto alla polacca

12. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: V. Tema con variazioni

13. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: V. Andante quasi allegretto

There are periods in the history of music, just as in that of any other artistic form or cultural endeavour, in which forms or genres or instruments which have their root in the past compete on a plan of equality with each other, until one of them wins the struggle for survival and more or less supplants the other or others.

One can think of instruments such as the arpeggione or the baryton, which seemed to have a great potential, but which rather quickly disappeared from the scene; or to the competitive beginnings of both the string quartet and the string trio, or of the piano quartet and piano trio. In the late eighteenth century, there was certainly the already impressive repertoire of string quartets by Franz Joseph Haydn; but it was not yet certain that the string quartet would definitively become “the” string ensemble par excellence. Of course, magnificent string trios would be written throughout the nineteenth, twentieth and twenty-first centuries, creating a repertoire which is both very challenging and very rewarding. However, in terms of quantity, it is undeniable that more quartets than trios have been created in the Romantic and modern era.

When Beethoven, as a young composer, was trying his hand at various genres, the game was still fully open. Indeed, he turned first to the string trio, delaying his encounter with the quartet for some more years. He had arrived since a couple of years in Vienna, having left his hometown, Bonn. His first approach to the Austrian capital was as a student, supported by his wealthy German patrons. One of them had famously wished him to become able to receive “Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands”.

He had studied under Haydn’s guidance, but, allegedly, he had not profited much from the older maestro’s teaching. This impression, as a matter of fact, may come more from their subsequent disagreements than from reality. It is true that their personality and character were very different from each other, and that Beethoven’s style would ultimately be markedly unlike Haydn’s. But it is also true that it appears rather clearly that Beethoven took several leaves out of Haydn’s book, and to deny this would be unfair.

During the time Haydn spent in London, Beethoven continued his education under the guidance of Albrechtsberger, who came from the circle of Bach enthusiasts and who furthered Beethoven’s knowledge of Bach’s works – in particular of the Well-Tempered Clavier.

The in-depth education received by Beethoven in terms of counterpoint and polyphony is already clear in his first works, and would become of primary import particularly in his late production.

When the time came for the composer to issue his first printed works, he deliberately chose genres and compositions which could represent his artistry and personality satisfactorily. For his op. 1 he elected a set of piano Trios, which reveal the maturity of his writing and of his creativity. His op. 2 is constituted by three piano Sonatas, of which particularly the third is already the masterpiece of a master. For his op. 3, he turned to a lesser common genre, i.e. that of the string Trio. It was a genre he would employ only in the first years of his career, probably with the goal in mind of proposing his music as pertaining to a different field from that usually inhabited by his mentor Haydn. It would take him some more time, as previously said, to tackle the string quartet. However, as has been rightfully written by Robert Simpson, “the quartet itself can by no stretch of the imagination be thought of as an enriched trio, or a proper trio as an impoverished quartet”.

Furthermore, the model not-so-implicitly looked at by this young Beethoven is not that of his teacher Haydn, but rather that of Mozart – Mozart whose spirit Beethoven’s patron wished him to receive from Haydn’s hands. The Mozartean stimulus is evident in terms of form, of content, of inspiration, but also of writing and style, even though many typically Beethovenian touches are already surfacing. While there is plenty of irony and tenderness, of humour and of lyricism in these works, Classicism is already on the verge of disappearing, and the more sharp-edged style of the young Beethoven emerges frequently under the patina of polished good manners of the Classical style.

The op. 3 Trio is set in six movements, and therefore it mirrors rather faithfully the model Beethoven rather clearly followed, i.e. the Divertimento for string trio in E flat KV 563, published in 1792, the year after Mozart’s death. (A similarly close inspiration is discernible in Beethoven’s Quintet for piano and winds, analogously following Mozart’s model). It is not just the number of movements, the scoring, and the key which the two works share; also the sequence of the movements is patterned after Mozart’s style, since in both works the Adagio is framed by two Minuets with trios.

This Trio was dedicated by Beethoven to Anna Margarete von Browne, the wife of a diplomat of Irish descent, Count Johann Georg von Browne-Camus. Her husband, the Count, was to be the dedicatee of the Trios op. 9 for strings, which will constitute the second movement of the Quodlibet Trio’s complete recording of Beethoven’s string trios. In both cases, dedicating a work to the Brownes would be a very wise move by Beethoven, since the aristocratic family was inclined to express their gratitude with generosity.

Their enthusiasm demonstrates their openness to the many novelties the young Beethoven was inserting into the Mozartean genre. Whilst the inspiration is clear, in fact, there are also numerous interventions which reveal the innovative approach of the young composer. For instance, the first movement opens with a rather destabilizing pattern of syncopations, and is rather unusually developed; part of its ironic attitude is revealed by the presence of a “false” recapitulation, which deceives the listener and anticipates by several minutes the coming of the true recapitulation of the Sonata form.

A more traditional version of the Sonata form is found in the Andante, punctuated by eloquent rests which transmit a feeling of intensity of expression. It is a movement which possesses an almost “prophetic” character inasmuch as it contains some impressive anticipations of typically Beethovenian gestures.

Another Beethovenian trait which would become increasingly fundamental in the composer’s mature years is the skilled, masterful, and brilliant use of counterpoint, particularly in the last movement. Beethoven had studied thoroughly Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, both as a keyboard player and as a composer, and the results of this in-depth analysis are clearly visible in his effortless management of the melodic lines. They intertwine with each other in a dense imitative fabric, but the refinement of the result does not sound artificial or demonstrative. Rather, just as happens with some among the best of Mozart’s works, polyphony sounds playful and elegant, turning Beethoven’s chamber music writing into that “conversation among intelligent people” which had been offered as a perfect synthesis of Haydn’s Quartet style.

Beethoven had planned a version of this work for piano trio, but abandoned the project leaving it unfinished. There is also a cello and piano version, published as op. 64.

Some years later, in 1797, Beethoven issued a Serenade for string trio. Serenades, just as Divertimenti, Cassations and similar works, were very popular at Beethoven’s time. However, these works frequently had virtually no artistic ambitions; they were simply entertaining compositions, not intended to be listened to with the attention one dedicates to a symphony or a quartet. Here, it is evident that Beethoven fully grasps the enjoyable, playful, and pleasant mood of this genre, but, at the same time, that playful does not mean empty for him, nor entertaining coincides with vacuous. Furthermore, it has been argued that this work may have been intended for legendary violinist Schuppanzigh, for whom Beethoven would write several of his later quartets.

There are, for instance, examples of complex rhythmic schemes, which transform the usual, normally unpretentious, March into something much more refined and demanding. This opening march, which is heard both at the beginning and at the end of the work, is a brilliant piece which immediately grips the listener’s attention.

Among the memorable moments of this work are the amusing and fanciful pizzicatos which conclude the Minuet and Trio; the lyrical opening of the second Adagio, with an intense dialogue among the instruments, and the surprising irruption of the Scherzo. Another gem is the Polonaise in the Allegretto movement: it is not “just” a beautiful movement, but also a rarity because this dance, widely employed in Baroque music, would resurface in the Romantic era, but had been much neglected at Beethoven’s time. The Theme with Variations is another anticipation of one of Beethoven’s major achievements, i.e. his unsurpassed mastery in the art of variation. Furthermore, the theme would later be re-employed by the composer who turned it into a Lied (“Sanft wie die Frühlingssonne”).

This piece too was to be transcribed, in this case for viola and piano, and published under Beethoven’s name as his op. 42, although Beethoven expressly denied his active involvement in this version, realized by Franz Xaver Kleinheinz.

Together, these works demonstrate the flexibility and fecundity of the ensemble chosen by Beethoven, and the composer’s ability – in spite of his young age – in intuiting the idiomatic potential of this trio of strings, whose specificity marks it distinctively in comparison with other, seemingly similar, ensembles.

01. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: I. Allegro con brio

02. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: II. Andante

03. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: III. Minuet. Allegretto

04. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: IV. Adagio

05. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: V. Minuet. Moderato

06. String Trio in E-Flat Major, Op. 3: VI. Finale. Allegro

07. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: I. Marcia. Allegro

08. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: I. Adagio

09. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: II. Minuet. Allegretto

10. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: III. Adagio

11. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: IV. Allegretto alla polacca

12. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: V. Tema con variazioni

13. Serenade for String Trio in D Major, Op. 8: V. Andante quasi allegretto

There are periods in the history of music, just as in that of any other artistic form or cultural endeavour, in which forms or genres or instruments which have their root in the past compete on a plan of equality with each other, until one of them wins the struggle for survival and more or less supplants the other or others.

One can think of instruments such as the arpeggione or the baryton, which seemed to have a great potential, but which rather quickly disappeared from the scene; or to the competitive beginnings of both the string quartet and the string trio, or of the piano quartet and piano trio. In the late eighteenth century, there was certainly the already impressive repertoire of string quartets by Franz Joseph Haydn; but it was not yet certain that the string quartet would definitively become “the” string ensemble par excellence. Of course, magnificent string trios would be written throughout the nineteenth, twentieth and twenty-first centuries, creating a repertoire which is both very challenging and very rewarding. However, in terms of quantity, it is undeniable that more quartets than trios have been created in the Romantic and modern era.

When Beethoven, as a young composer, was trying his hand at various genres, the game was still fully open. Indeed, he turned first to the string trio, delaying his encounter with the quartet for some more years. He had arrived since a couple of years in Vienna, having left his hometown, Bonn. His first approach to the Austrian capital was as a student, supported by his wealthy German patrons. One of them had famously wished him to become able to receive “Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands”.

He had studied under Haydn’s guidance, but, allegedly, he had not profited much from the older maestro’s teaching. This impression, as a matter of fact, may come more from their subsequent disagreements than from reality. It is true that their personality and character were very different from each other, and that Beethoven’s style would ultimately be markedly unlike Haydn’s. But it is also true that it appears rather clearly that Beethoven took several leaves out of Haydn’s book, and to deny this would be unfair.

During the time Haydn spent in London, Beethoven continued his education under the guidance of Albrechtsberger, who came from the circle of Bach enthusiasts and who furthered Beethoven’s knowledge of Bach’s works – in particular of the Well-Tempered Clavier.

The in-depth education received by Beethoven in terms of counterpoint and polyphony is already clear in his first works, and would become of primary import particularly in his late production.

When the time came for the composer to issue his first printed works, he deliberately chose genres and compositions which could represent his artistry and personality satisfactorily. For his op. 1 he elected a set of piano Trios, which reveal the maturity of his writing and of his creativity. His op. 2 is constituted by three piano Sonatas, of which particularly the third is already the masterpiece of a master. For his op. 3, he turned to a lesser common genre, i.e. that of the string Trio. It was a genre he would employ only in the first years of his career, probably with the goal in mind of proposing his music as pertaining to a different field from that usually inhabited by his mentor Haydn. It would take him some more time, as previously said, to tackle the string quartet. However, as has been rightfully written by Robert Simpson, “the quartet itself can by no stretch of the imagination be thought of as an enriched trio, or a proper trio as an impoverished quartet”.

Furthermore, the model not-so-implicitly looked at by this young Beethoven is not that of his teacher Haydn, but rather that of Mozart – Mozart whose spirit Beethoven’s patron wished him to receive from Haydn’s hands. The Mozartean stimulus is evident in terms of form, of content, of inspiration, but also of writing and style, even though many typically Beethovenian touches are already surfacing. While there is plenty of irony and tenderness, of humour and of lyricism in these works, Classicism is already on the verge of disappearing, and the more sharp-edged style of the young Beethoven emerges frequently under the patina of polished good manners of the Classical style.

The op. 3 Trio is set in six movements, and therefore it mirrors rather faithfully the model Beethoven rather clearly followed, i.e. the Divertimento for string trio in E flat KV 563, published in 1792, the year after Mozart’s death. (A similarly close inspiration is discernible in Beethoven’s Quintet for piano and winds, analogously following Mozart’s model). It is not just the number of movements, the scoring, and the key which the two works share; also the sequence of the movements is patterned after Mozart’s style, since in both works the Adagio is framed by two Minuets with trios.

This Trio was dedicated by Beethoven to Anna Margarete von Browne, the wife of a diplomat of Irish descent, Count Johann Georg von Browne-Camus. Her husband, the Count, was to be the dedicatee of the Trios op. 9 for strings, which will constitute the second movement of the Quodlibet Trio’s complete recording of Beethoven’s string trios. In both cases, dedicating a work to the Brownes would be a very wise move by Beethoven, since the aristocratic family was inclined to express their gratitude with generosity.

Their enthusiasm demonstrates their openness to the many novelties the young Beethoven was inserting into the Mozartean genre. Whilst the inspiration is clear, in fact, there are also numerous interventions which reveal the innovative approach of the young composer. For instance, the first movement opens with a rather destabilizing pattern of syncopations, and is rather unusually developed; part of its ironic attitude is revealed by the presence of a “false” recapitulation, which deceives the listener and anticipates by several minutes the coming of the true recapitulation of the Sonata form.

A more traditional version of the Sonata form is found in the Andante, punctuated by eloquent rests which transmit a feeling of intensity of expression. It is a movement which possesses an almost “prophetic” character inasmuch as it contains some impressive anticipations of typically Beethovenian gestures.

Another Beethovenian trait which would become increasingly fundamental in the composer’s mature years is the skilled, masterful, and brilliant use of counterpoint, particularly in the last movement. Beethoven had studied thoroughly Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, both as a keyboard player and as a composer, and the results of this in-depth analysis are clearly visible in his effortless management of the melodic lines. They intertwine with each other in a dense imitative fabric, but the refinement of the result does not sound artificial or demonstrative. Rather, just as happens with some among the best of Mozart’s works, polyphony sounds playful and elegant, turning Beethoven’s chamber music writing into that “conversation among intelligent people” which had been offered as a perfect synthesis of Haydn’s Quartet style.

Beethoven had planned a version of this work for piano trio, but abandoned the project leaving it unfinished. There is also a cello and piano version, published as op. 64.

Some years later, in 1797, Beethoven issued a Serenade for string trio. Serenades, just as Divertimenti, Cassations and similar works, were very popular at Beethoven’s time. However, these works frequently had virtually no artistic ambitions; they were simply entertaining compositions, not intended to be listened to with the attention one dedicates to a symphony or a quartet. Here, it is evident that Beethoven fully grasps the enjoyable, playful, and pleasant mood of this genre, but, at the same time, that playful does not mean empty for him, nor entertaining coincides with vacuous. Furthermore, it has been argued that this work may have been intended for legendary violinist Schuppanzigh, for whom Beethoven would write several of his later quartets.

There are, for instance, examples of complex rhythmic schemes, which transform the usual, normally unpretentious, March into something much more refined and demanding. This opening march, which is heard both at the beginning and at the end of the work, is a brilliant piece which immediately grips the listener’s attention.

Among the memorable moments of this work are the amusing and fanciful pizzicatos which conclude the Minuet and Trio; the lyrical opening of the second Adagio, with an intense dialogue among the instruments, and the surprising irruption of the Scherzo. Another gem is the Polonaise in the Allegretto movement: it is not “just” a beautiful movement, but also a rarity because this dance, widely employed in Baroque music, would resurface in the Romantic era, but had been much neglected at Beethoven’s time. The Theme with Variations is another anticipation of one of Beethoven’s major achievements, i.e. his unsurpassed mastery in the art of variation. Furthermore, the theme would later be re-employed by the composer who turned it into a Lied (“Sanft wie die Frühlingssonne”).

This piece too was to be transcribed, in this case for viola and piano, and published under Beethoven’s name as his op. 42, although Beethoven expressly denied his active involvement in this version, realized by Franz Xaver Kleinheinz.

Together, these works demonstrate the flexibility and fecundity of the ensemble chosen by Beethoven, and the composer’s ability – in spite of his young age – in intuiting the idiomatic potential of this trio of strings, whose specificity marks it distinctively in comparison with other, seemingly similar, ensembles.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads