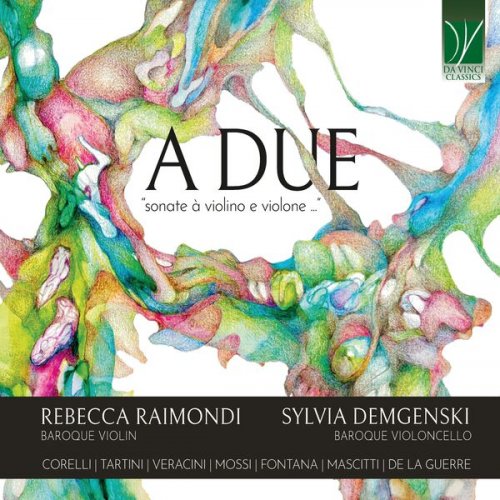

Rebecca Raimondi, Sylvia Demgenski - A DUE - Sonate à violino e violone (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Rebecca Raimondi, Sylvia Demgenski

- Title: A DUE - Sonate à violino e violone

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:10:28

- Total Size: 370 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Sonate a 1 2. 3. per il violin, o cornetto, fagotto, chitarone, violoncino o simile altro istromento in C Major: I. Violin Sonata

02. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 5 No. 4: I. Adagio

03. Violin Sonata in F major in F Major, Op. 5 No. 4: II. Allegro

04. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 5 No. 4: III. Vivace

05. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 5 No. 4: IV. Adagio

06. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 5 No. 4: V. Allegro

07. Sonata No. 2 in D Major: I. Presto

08. Sonata No. 2 in D Major: II. Adagio

09. Sonata No. 2 in D Major: III. Presto

10. Sonata No. 2 in D Major: IV. Presto

11. Sonata in No. 5 and Capriccio 6 in G Minor: I. Adagio Assai

12. Sonata in No. 5 and Capriccio 6 in G Minor: II. Capriccio con due Soggetti, Allegro assai

13. Sonata in No. 5 and Capriccio 6 in G Minor: III. Giga

14. 12 Violin Sonatas and a Pastorale in C Major, Op. 1: I. Violin Sonata - Grave

15. 12 Violin Sonatas and a Pastorale in C Major, Op. 1: II. Violin Sonata - Allegro

16. 12 Violin Sonatas and a Pastorale in C Major, Op. 1: III. Violin Sonata - Allegro

17. Sonata No. 11 in C Minor: I. Adagio

18. Sonata No. 11 in C Minor: II. Allegro

19. Sonata No. 11 in C Minor: III. Adagio

20. Sonata No. 11 in C Minor: IV. Allegro moderato

21. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: I. Grand Air - Vivace

22. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: II. Les Vents - Allegro

23. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: III. Festes Galantes - Sarabanda, Largo

24. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: IV. Badinage - Allegro

25. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: V. Du Sommeil - Largo e Piano

26. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: VI. L'amour en couroux en desespoir - Allegro e Staccato - Presto - Adagio

27. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: VII. Calme Amoureux - Minore, Largo

28. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: VIII. La Noce - Magiore, Allemanda

29. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: IX. Suitte de la Noce - Forlana, Allegro

30. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: X. Dernière Suitte de la Noce - Allegro

It’s not uncommon for a musicologist to be asked by people who are interested in classical music: “But what is a continuo?” There is no simple answer because that word – crucial as it is for understanding the composition and performance practice of the 17th and 18th centuries – is an umbrella term under which many different realities find refuge.

Literally, continuo means “continuous”; it is an adjective that implies a noun, i.e. basso. “Basso” refers to the lowest line of a musical composition. In the golden era of polyphony, the bass was one among several equal voices of the contrapuntal texture – it intervened as frequently or as rarely as every other part, and engaged in imitating the musical material of the others. Therefore, the bass line, just as any voice, was characterized by both notes and rests, by musical phrases and silence in between.

Due to numerous historical and aesthetic reasons – including the influence of Humanism which stressed the importance of text intelligibility – the intricate polyphonies of the 14th-16th centuries progressively gave way to “homophony”, which is a different kind of compositional technique. Instead of voices entering and exiting the musical structure independently, now they tended to sing in rhythmic unison. This allowed for a much better understanding of the text, but changed the way of writing music from polyphony to harmony, from the imitative style to the chordal style. This in turn prompted an epoch-making shift of paradigm, from modality in the middle ages and renaissance, to tonality, the system typical of the modern era.

Since the voices now tended to move together, it was possible to sing just one of them, typically the uppermost, and to play the others on an instrument capable of producing chords – typically the lute, or keyboard instruments such as the clavichord. This in turn undermined the equality which had characterized the relationship between voices in a polyphonic texture until then. The uppermost part, i.e. the soprano, became the most important line, but the bass line also acquired pre-eminence, since it determined the harmony above it.

Thus the character of the bass voice changed, from the previously typical melodic line – including rests like any other part – to a “continuous” (instrumental) line. It was the “basso continuo”.

So, this is how the continuo was born; but this has not really answered our musical friend’s question: “But what is a continuo?”. It is not an instrument, like a bassoon or a harpsichord. It is, one might say, a technique; but it is also “something” which actually sounds, even though, again, it is not an instrument. It is – normally – a small ensemble whose line-up is generally left to the performers’ choice. Nowadays, the continuo is performed with one or more melodic, low-pitched instruments, such as the cello, the viola da gamba, or the bassoon, and one or more “harmonic” instruments, such as the theorbo, the harpsichord, the organ, the lute or any other instrument capable of producing chordal progressions. The melodic instrument(s) play the bass line, while the others “realize” the continuo, i.e. perform the chords which are normally indicated through a special system of ciphering called “figured bass” – for instance, in one system a triad in the root position is indicated as “5 3”.

This brings us to what is distinctive about this original and unusual Da Vinci Classics album. Any given series of chords has a bass line – albeit probably ungrammatical – formed of its lowest notes. One might imagine, however, that a solo bass line does not necessarily communicate harmony; however, the human mind (particularly if it is familiar with the processes of european tonal harmony) tends to “fill” the gaps in the harmony, just as happens with optical phenomena – think of a half-hidden silhouette whose shape is easily reconstructed by our brain. This is the principle upon which works for unaccompanied melodic instruments, such as Bach’s violin Sonatas and Partitas, or his Suites for violoncello are built. Given a bass and a soprano line, it is easy to imagine the harmonic filling, and this in fact happens quite unconsciously.

It was upon just this principle that this album was conceived; no arbitrary decision, since it merely reflects common practices of the Baroque era.

Indeed it was historically documented practice for the great violinists and composers of the italian Baroque – Corelli, Tartini and Veracini – to undertake entire concert tours exclusively with their cellists: i.e. a soprano line (the violin) and its continuo (the cello). Nowadays, people are used to accompanying violin sonatas with a keyboard instrument. However, when two string instruments combine to perform these works, the music is created in a completely new way. On the one hand, the reduction of complexity in the basso continuo poses new challenges to the cellist; on the other, a duo of violin and cello opens up entirely new, almost orchestral sonorities. With this idea in mind, the recording artists have made a selection of interesting pieces that highlight the strengths of this instrumentation, including a hitherto unrecorded composition by Giovanni Mossi.

There are some fascinating period sources which confirm the widespread dissemination of this practice. For instance, Giuseppe Tartini traveled to Prague with his friend Antonio Vandini, the first violoncellist of the Paduan chapel. Similarly, Arcangelo Corelli performed with the cellist Francischello, and Francesco Veracini with Salvatore Lanzetti; there was also the famous case of double-bassist Dragonetti and cellist Lindley at the Italian Theatre in London from 1794 until 1846, a duo that was celebrated for their interpretations of continuo parts in recitatives, and which also performed solo concerts where the double bass was the continuo for the solo violoncello. As Lew Solomonowitsch Ginsburg and Albert Palm affirm, “when the violinist of the time performed sonatas for violin and bass, he usually traveled together with the cellist, who accompanied him from the single-line bass part, as a harpsichordist or organist did by no means always play the bass part together with the cellist. In the absence of a keyboard instrument, the role of the accompanist on the cello was one of particular responsibility. At that time, the art of accompaniment was of special importance as it required tonal-musical taste, sensitivity, a precise knowledge of harmony and polyphony, improvisational skills and experience”.

Charles Burney – one of the most authoritative sources for 18th century music – wrote regarding Veracini: “Being called upon, [Veracini] would not play a concerto, but desired [to] play a solo at the bottom of the choir, desiring Lanzetti, the violoncellist of Turin to accompany him; when he played in such a manner as to extort an e viva! in the public church. And whenever he was about to make a close, he turned to Laurenti, and called out: ‘Cosi si suona per fare il primo violino’: ‘this is the way to play the first fiddle’”.

Recent research by Giovanna Barbati indicates that cello players trained in the Italian partimento tradition were expected not only to play the written notes, but to engage in harmonic realization of the bass line, enriching it with embellishments and diminutions. Indeed, the study of the partimento technique and of its teaching in the Neapolitan Conservatories suggests that all instrumentalists of that time were educated to be capable of improvising and composing over a bass line. This skill, once acquired, was unlikely to remain dormant, but was very probably put to use in concert practice.

The recording artists, inspired by the titles of opuses by Corelli and Tartini, which read ‘per violino e violone/violoncello o cembalo’, began to question whether the ‘o’ (‘or’) might imply performance alternatives – and concluded that the pieces could indeed be performed as duos. The term “Violone” was used to describe many different instruments, but always referred to bass string instruments, and in this case probably the modern form of the cello, since it is documented that Corelli and Veracini travelled with their own cellists.

This notion was further corroborated by the artists’ observation that Mossi’s sonatas op. 5 are titled “12 Sonate o sinfonie a violino solo con il violoncello”, not even mentioning another instrument for the continuo. The bass line includes figures, but since Giovanna Barbati’s research suggests that cellists were expected to realize the harmonies, this does not indicate that the part was actually meant for a keyboard instrument. Continuo chords could also have been added for monetary purposes when it was published, in order to reach a wider audience.

Among the recorded works some highlights should be pointed out. First is the very interesting and unusual form of Mascitti’s Suite, which is an instrumental retelling of the famous Greek myth of Eros and Psyche, illustrated through a series of dances and of mini-suites evoking the various moments of their love-story.

Another composer worth mentioning here is Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, one of the most interesting female composers of the Baroque era. Her sonatas have a very prominent Italian stylistic influence. Considering the movement of the bass line, her sonatas are more in the form of a “duo” between the upper voice and the bass, and are in this way similar to the compositions of Corelli, Veracini and Tartini. Although the title only mentions the cembalo as a continuo instrument, her writing allows for performance with cello only. The same applies to Mascitti and Veracini, whose title pages mention only “basso/basso continuo”, but whose scoring – also in consideration of Veracini’s documented cooperation with a cellist – seems to support this particular performance.

Also worth mentioning is the special form of Veracini’s sonata, which is a compilation of two works. The artists followed Veracini’s suggestion in the preface of this opus to combine the sonatas to form a new composition consisting of two or three movements. In this CD the sonata no. 5 and the capriccio no. 6 have been combined.

Finally, with regard to Fontana, the performers consider the modern violoncello sufficiently similar to the instruments named in the score – ‘fagotto, chitarone, violoncino o simile altro istromento’ – and contend that this explicit openness to alternative instrumentation supports their historically informed choice, despite the cello not yet existing in its current form at the time. He scores his composition for a high and a low voice; at that time it was common practice for both parts to be embellished with diminutions. The artists see a clear trajectory from this custom of melodic improvisation, to the practice of embellished continuo realisation on a bass stringed instrument, accompanying the ornamented melody in the high voice. The bass line is thus ‘realised’ in a proper sense – its latent harmonic content is unfolded.

Taken together, these works trace a compelling path through the diverse possibilities available to performers. Such choices, though frequently underexplored, vividly demonstrate the expressive range afforded by historically informed performance practice.

01. Sonate a 1 2. 3. per il violin, o cornetto, fagotto, chitarone, violoncino o simile altro istromento in C Major: I. Violin Sonata

02. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 5 No. 4: I. Adagio

03. Violin Sonata in F major in F Major, Op. 5 No. 4: II. Allegro

04. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 5 No. 4: III. Vivace

05. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 5 No. 4: IV. Adagio

06. Violin Sonata in F Major, Op. 5 No. 4: V. Allegro

07. Sonata No. 2 in D Major: I. Presto

08. Sonata No. 2 in D Major: II. Adagio

09. Sonata No. 2 in D Major: III. Presto

10. Sonata No. 2 in D Major: IV. Presto

11. Sonata in No. 5 and Capriccio 6 in G Minor: I. Adagio Assai

12. Sonata in No. 5 and Capriccio 6 in G Minor: II. Capriccio con due Soggetti, Allegro assai

13. Sonata in No. 5 and Capriccio 6 in G Minor: III. Giga

14. 12 Violin Sonatas and a Pastorale in C Major, Op. 1: I. Violin Sonata - Grave

15. 12 Violin Sonatas and a Pastorale in C Major, Op. 1: II. Violin Sonata - Allegro

16. 12 Violin Sonatas and a Pastorale in C Major, Op. 1: III. Violin Sonata - Allegro

17. Sonata No. 11 in C Minor: I. Adagio

18. Sonata No. 11 in C Minor: II. Allegro

19. Sonata No. 11 in C Minor: III. Adagio

20. Sonata No. 11 in C Minor: IV. Allegro moderato

21. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: I. Grand Air - Vivace

22. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: II. Les Vents - Allegro

23. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: III. Festes Galantes - Sarabanda, Largo

24. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: IV. Badinage - Allegro

25. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: V. Du Sommeil - Largo e Piano

26. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: VI. L'amour en couroux en desespoir - Allegro e Staccato - Presto - Adagio

27. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: VII. Calme Amoureux - Minore, Largo

28. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: VIII. La Noce - Magiore, Allemanda

29. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: IX. Suitte de la Noce - Forlana, Allegro

30. Sonata No. 12 Psiché, Divertissement: X. Dernière Suitte de la Noce - Allegro

It’s not uncommon for a musicologist to be asked by people who are interested in classical music: “But what is a continuo?” There is no simple answer because that word – crucial as it is for understanding the composition and performance practice of the 17th and 18th centuries – is an umbrella term under which many different realities find refuge.

Literally, continuo means “continuous”; it is an adjective that implies a noun, i.e. basso. “Basso” refers to the lowest line of a musical composition. In the golden era of polyphony, the bass was one among several equal voices of the contrapuntal texture – it intervened as frequently or as rarely as every other part, and engaged in imitating the musical material of the others. Therefore, the bass line, just as any voice, was characterized by both notes and rests, by musical phrases and silence in between.

Due to numerous historical and aesthetic reasons – including the influence of Humanism which stressed the importance of text intelligibility – the intricate polyphonies of the 14th-16th centuries progressively gave way to “homophony”, which is a different kind of compositional technique. Instead of voices entering and exiting the musical structure independently, now they tended to sing in rhythmic unison. This allowed for a much better understanding of the text, but changed the way of writing music from polyphony to harmony, from the imitative style to the chordal style. This in turn prompted an epoch-making shift of paradigm, from modality in the middle ages and renaissance, to tonality, the system typical of the modern era.

Since the voices now tended to move together, it was possible to sing just one of them, typically the uppermost, and to play the others on an instrument capable of producing chords – typically the lute, or keyboard instruments such as the clavichord. This in turn undermined the equality which had characterized the relationship between voices in a polyphonic texture until then. The uppermost part, i.e. the soprano, became the most important line, but the bass line also acquired pre-eminence, since it determined the harmony above it.

Thus the character of the bass voice changed, from the previously typical melodic line – including rests like any other part – to a “continuous” (instrumental) line. It was the “basso continuo”.

So, this is how the continuo was born; but this has not really answered our musical friend’s question: “But what is a continuo?”. It is not an instrument, like a bassoon or a harpsichord. It is, one might say, a technique; but it is also “something” which actually sounds, even though, again, it is not an instrument. It is – normally – a small ensemble whose line-up is generally left to the performers’ choice. Nowadays, the continuo is performed with one or more melodic, low-pitched instruments, such as the cello, the viola da gamba, or the bassoon, and one or more “harmonic” instruments, such as the theorbo, the harpsichord, the organ, the lute or any other instrument capable of producing chordal progressions. The melodic instrument(s) play the bass line, while the others “realize” the continuo, i.e. perform the chords which are normally indicated through a special system of ciphering called “figured bass” – for instance, in one system a triad in the root position is indicated as “5 3”.

This brings us to what is distinctive about this original and unusual Da Vinci Classics album. Any given series of chords has a bass line – albeit probably ungrammatical – formed of its lowest notes. One might imagine, however, that a solo bass line does not necessarily communicate harmony; however, the human mind (particularly if it is familiar with the processes of european tonal harmony) tends to “fill” the gaps in the harmony, just as happens with optical phenomena – think of a half-hidden silhouette whose shape is easily reconstructed by our brain. This is the principle upon which works for unaccompanied melodic instruments, such as Bach’s violin Sonatas and Partitas, or his Suites for violoncello are built. Given a bass and a soprano line, it is easy to imagine the harmonic filling, and this in fact happens quite unconsciously.

It was upon just this principle that this album was conceived; no arbitrary decision, since it merely reflects common practices of the Baroque era.

Indeed it was historically documented practice for the great violinists and composers of the italian Baroque – Corelli, Tartini and Veracini – to undertake entire concert tours exclusively with their cellists: i.e. a soprano line (the violin) and its continuo (the cello). Nowadays, people are used to accompanying violin sonatas with a keyboard instrument. However, when two string instruments combine to perform these works, the music is created in a completely new way. On the one hand, the reduction of complexity in the basso continuo poses new challenges to the cellist; on the other, a duo of violin and cello opens up entirely new, almost orchestral sonorities. With this idea in mind, the recording artists have made a selection of interesting pieces that highlight the strengths of this instrumentation, including a hitherto unrecorded composition by Giovanni Mossi.

There are some fascinating period sources which confirm the widespread dissemination of this practice. For instance, Giuseppe Tartini traveled to Prague with his friend Antonio Vandini, the first violoncellist of the Paduan chapel. Similarly, Arcangelo Corelli performed with the cellist Francischello, and Francesco Veracini with Salvatore Lanzetti; there was also the famous case of double-bassist Dragonetti and cellist Lindley at the Italian Theatre in London from 1794 until 1846, a duo that was celebrated for their interpretations of continuo parts in recitatives, and which also performed solo concerts where the double bass was the continuo for the solo violoncello. As Lew Solomonowitsch Ginsburg and Albert Palm affirm, “when the violinist of the time performed sonatas for violin and bass, he usually traveled together with the cellist, who accompanied him from the single-line bass part, as a harpsichordist or organist did by no means always play the bass part together with the cellist. In the absence of a keyboard instrument, the role of the accompanist on the cello was one of particular responsibility. At that time, the art of accompaniment was of special importance as it required tonal-musical taste, sensitivity, a precise knowledge of harmony and polyphony, improvisational skills and experience”.

Charles Burney – one of the most authoritative sources for 18th century music – wrote regarding Veracini: “Being called upon, [Veracini] would not play a concerto, but desired [to] play a solo at the bottom of the choir, desiring Lanzetti, the violoncellist of Turin to accompany him; when he played in such a manner as to extort an e viva! in the public church. And whenever he was about to make a close, he turned to Laurenti, and called out: ‘Cosi si suona per fare il primo violino’: ‘this is the way to play the first fiddle’”.

Recent research by Giovanna Barbati indicates that cello players trained in the Italian partimento tradition were expected not only to play the written notes, but to engage in harmonic realization of the bass line, enriching it with embellishments and diminutions. Indeed, the study of the partimento technique and of its teaching in the Neapolitan Conservatories suggests that all instrumentalists of that time were educated to be capable of improvising and composing over a bass line. This skill, once acquired, was unlikely to remain dormant, but was very probably put to use in concert practice.

The recording artists, inspired by the titles of opuses by Corelli and Tartini, which read ‘per violino e violone/violoncello o cembalo’, began to question whether the ‘o’ (‘or’) might imply performance alternatives – and concluded that the pieces could indeed be performed as duos. The term “Violone” was used to describe many different instruments, but always referred to bass string instruments, and in this case probably the modern form of the cello, since it is documented that Corelli and Veracini travelled with their own cellists.

This notion was further corroborated by the artists’ observation that Mossi’s sonatas op. 5 are titled “12 Sonate o sinfonie a violino solo con il violoncello”, not even mentioning another instrument for the continuo. The bass line includes figures, but since Giovanna Barbati’s research suggests that cellists were expected to realize the harmonies, this does not indicate that the part was actually meant for a keyboard instrument. Continuo chords could also have been added for monetary purposes when it was published, in order to reach a wider audience.

Among the recorded works some highlights should be pointed out. First is the very interesting and unusual form of Mascitti’s Suite, which is an instrumental retelling of the famous Greek myth of Eros and Psyche, illustrated through a series of dances and of mini-suites evoking the various moments of their love-story.

Another composer worth mentioning here is Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, one of the most interesting female composers of the Baroque era. Her sonatas have a very prominent Italian stylistic influence. Considering the movement of the bass line, her sonatas are more in the form of a “duo” between the upper voice and the bass, and are in this way similar to the compositions of Corelli, Veracini and Tartini. Although the title only mentions the cembalo as a continuo instrument, her writing allows for performance with cello only. The same applies to Mascitti and Veracini, whose title pages mention only “basso/basso continuo”, but whose scoring – also in consideration of Veracini’s documented cooperation with a cellist – seems to support this particular performance.

Also worth mentioning is the special form of Veracini’s sonata, which is a compilation of two works. The artists followed Veracini’s suggestion in the preface of this opus to combine the sonatas to form a new composition consisting of two or three movements. In this CD the sonata no. 5 and the capriccio no. 6 have been combined.

Finally, with regard to Fontana, the performers consider the modern violoncello sufficiently similar to the instruments named in the score – ‘fagotto, chitarone, violoncino o simile altro istromento’ – and contend that this explicit openness to alternative instrumentation supports their historically informed choice, despite the cello not yet existing in its current form at the time. He scores his composition for a high and a low voice; at that time it was common practice for both parts to be embellished with diminutions. The artists see a clear trajectory from this custom of melodic improvisation, to the practice of embellished continuo realisation on a bass stringed instrument, accompanying the ornamented melody in the high voice. The bass line is thus ‘realised’ in a proper sense – its latent harmonic content is unfolded.

Taken together, these works trace a compelling path through the diverse possibilities available to performers. Such choices, though frequently underexplored, vividly demonstrate the expressive range afforded by historically informed performance practice.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads