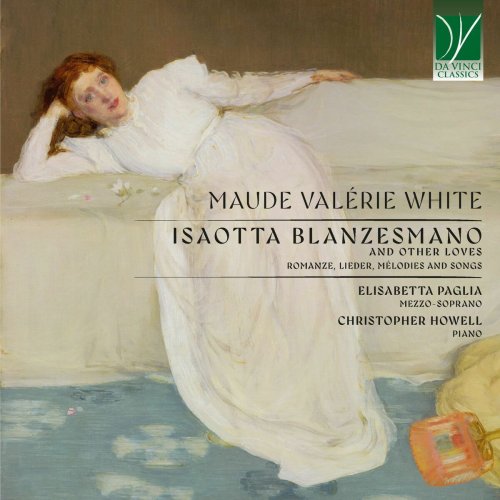

Christopher Howell - Maude Valérie White: Isaotta Blanzesman, and Other Loves (Romanze, Lieder, Mélodies and Songs) (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Christopher Howell, Elisabetta Paglia

- Title: Maude Valérie White: Isaotta Blanzesman, and Other Loves (Romanze, Lieder, Mélodies and Songs)

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 67:24 min

- Total Size: 282 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Isaotta Blanzesmano

02. Canzoncina pastorale

03. Waiting (Tuscan Folk-Song)

04. Serenata española

05. Im wunderschönen Monat Mai

06. Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen

07. Hör' ich das Liedchen klingen

08. Die Himmelsaugen

09. Stille Tränen

10. Das Meer hat seinen Perlen

11. Espoir en Dieu

12. Si j'étais Dieu

13. Le départ du conscrit

14. On the Fields of France

15. How do I love thee:

16. So we'll go no more a roving

17. A Greeting

18. Three Little Songs: No. 1, When the swallows homeward fly (From a German folk-song)

19. Three Little Songs: No. 2, A Memory

20. Three Little Songs: No. 3, Let us forget

21. Absent yet Present

22. Ask Not

01. Isaotta Blanzesmano

02. Canzoncina pastorale

03. Waiting (Tuscan Folk-Song)

04. Serenata española

05. Im wunderschönen Monat Mai

06. Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen

07. Hör' ich das Liedchen klingen

08. Die Himmelsaugen

09. Stille Tränen

10. Das Meer hat seinen Perlen

11. Espoir en Dieu

12. Si j'étais Dieu

13. Le départ du conscrit

14. On the Fields of France

15. How do I love thee:

16. So we'll go no more a roving

17. A Greeting

18. Three Little Songs: No. 1, When the swallows homeward fly (From a German folk-song)

19. Three Little Songs: No. 2, A Memory

20. Three Little Songs: No. 3, Let us forget

21. Absent yet Present

22. Ask Not

For the following biographical sketch of Maude Valérie White, I am indebted to Sophie Fuller’s 1998 thesis “Women composers during the British renaissance 1880-1918” (King’s College, London), available online.

White was born in Dieppe on 23 June 1855 to English parents. The family moved to the UK before she reached the age of one. Aged seven, she spent two years in Heidelberg with her German governess, returning in 1864. The following year she was sent to school in Paris for three years, during which period her father died. Back in London, in 1868, she stayed with George Rose-Innes, a trustee of the White family who became something of a father figure. Rose-Innes, from Chile, enabled her to add Spanish to her store of languages and also introduced her to Italian opera, a potent melodic counterbalance to the strictly classical diet of her piano lessons up till that time. White published her first song in 1974. In 1874-5 she was in Torquay, where she took lessons in harmony and counterpoint from W.S. Rockstro, and in 1876 was admitted to the Royal Academy of Music, where she studied composition with Sir George Macfarren. In 1879 she became the first woman to obtain the Mendelssohn scholarship. In 1881, however, her mother died and White, distraught, abandoned the scholarship and went to Chile for ten months, where her sister was staying with the Rose-Innes family. Her return to London in 1882 coincided with the death of George Rose-Innes and she took a room on her own – a bold step for a woman in Victorian society.

White had by now a burgeoning portfolio of published compositions. The White family had been neither poor nor particularly wealthy and from now on she depended on her own efforts for an income – teaching piano if necessary, publishing songs and organizing concerts of her own music for preference. She also used her linguistic skills to translate books and poetry. Unlike many women song composers in the Victorian period, she remained unmarried – the nearest she came to a sentimental attachment, so far as is known, was her longstanding friendship with Robert Hichens (1864-1950), a homosexual writer and aesthete associated with Oscar Wilde and Alfred Douglas who introduced her to the beauties of Italy.

In 1883, White went to Vienna to study for six months with Robert Fuchs. Fuchs, and Macfarren before him, was concerned that White had written no large-scale works. Both tried to persuade her to write a piano concerto and both came to agree that songs and miniatures were her comfort zone. She did later attempt an opera (unfinished) and a ballet.

In her heyday, till the end of the century and, to some extent, until 1914, White enjoyed a high reputation and a more than adequate income on the strength of her compositions – enough to enable her to travel frequently. This was partly a matter of cultural curiosity, but ill-health increasingly obliged her to choose spa towns and places noted for their favourable climate. From 1901, encouraged by Hichens, she made Taormina, Sicily, her base, moving to Florence after the 1908 Messina earthquake. For a period, she was also in Rome, sharing accommodation with her sister. Her compositions petered out (the last was published in 1927) and, in the post-1918 world, she seemed a figure from the past. She published two volumes of memories and spent her last years in London, where she died in 1937.

The current interest in women composers has only marginally touched Maude Valérie White. Perhaps her almost exclusive output of songs is felt to play into the hands of those who dismiss Victorian women composers as the musical equivalent of the Victorian lady with her sketch book and amateur watercolours. Her one-time popularity, and even the name Maude, tempt commentators to include her in a blanket dismissal of female amateurs. This is grossly unfair. As seen above, White had a thorough professional training and, from approximately 1880 to 1914, supported herself almost exclusively through her compositions. Not many male composers managed this in those years. Above all, it is grossly unjust in view of the generally high standard and wide range of her songs. This latter point may arouse perplexity. White may seem a different composer according to the language she is setting – the five sung here are not the only ones. Is there a “real White” with a personal voice underlying this stylistic roving? Probably we need a fuller knowledge of her work to answer this.

Isaotta Blanzesmano, with its claustrophobic, decadent atmosphere and fragile longing, could easily have been written by Mascagni, a composer much associated with D’Annunzio. It also reveals White’s love of sweeping, arpeggiated chords, which lend sumptuousness even to her simplest accompaniments. The Canzoncina pastorale arrangement is a case in point. White also incorporated this melody in her piano suite From the Ionian Sea. Lullabies by Mary to the child Jesus are frequent in all Italian regions, but I have not identified the original of this one. Waiting, included in this group because of its Italian theme, combines two unrelated Tuscan Rispetti translated very freely by John Addington Symonds. White adheres more closely here to a traditional ballad form. The chattering accompaniment and brittle rhythms of the Serenata Española may be a reminder that White knew Spanish culture mainly by way of Chile. The text seems an essentially masculine one, but the score states that the song is for “baritone or mezzo-soprano”, thus authorizing the present performance.

The German Lieder, presumably products of White’s period of study with Fuchs in Vienna in 1883, were published between that year and 1885. Anybody coming to them blind might suppose them to be by Schumann – and worthy products of his pen. Closer examination will find the paradox that White has set, in four of the songs here, texts almost indelibly associated with Schumann, but treating them so differently as to imply a reproach to the German master. Ears accustomed to Dichterliebe – and what lover of Lieder is not? – will be startled to find Im wunderschönen Monat Mai not a dreamlike evocation of a time when the poet might still hope in requited love, but a sprightly expression of a young man’s aspirations. In the love-tangle of Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen, Schumann’s folksy lilt implies this is the way of the world, we just have to put up with it, while White, perhaps taking the maiden’s part, adopts a doleful, almost tragic tone. In Hör’ ich das Liedchen klingen, Schumann strains his ear to hear the now distant melodies, while White takes her cue from Heine’s “stormy winds and rain”, which beat relentlessly throughout the song. It was presumably not White’s intention to create an “anti-Dichterliebe”. Rather, the two composers had different agendas. Schumann had strung together Heine’s miniatures to create a single narrative, giving them implied meanings in their new context that, as White readily spotted, they did not have when taken singly.

Of the other Lieder sung here, Schumann set just one – Stille Tränen. White replaces Schumann’s steadily pulsating accompaniment with a piano fantasy that the master would surely not have disowned. Die Himmelsaugen shows White’s ability to create a strikingly rich effect with the simplest means. This song might almost have been written by the young Richard Strauss. Das Meer hat seine Perlen, thanks to Longfellow’s rendering, is perhaps Heine’s most famous poem in the English-speaking world. It has been set by many composers, with general preference for an idyllic treatment. White opts for galloping passion.

Espoir en Dieu was one of White’s earliest successes. The model here may be Gounod. If White cannot quite achieve the fruity memorability of that master’s Repentir, she matches most of his other songs in religious vein. The later Si j’étais Dieu is closer to Fauré, though with an extra burst of passionate adrenalin. The other two songs in this group are much later and reflect White’s response to the Great War. Le depart du conscript, with a text by White herself, is a dialogue between the departing soldier and his sweetheart. The two never sing together and there is no indication that White intended it to be divided between two singers. The texture is more austere than in the earlier songs, creating a powerfully brooding atmosphere that saves the potentially mawkish sentimentality of the words. On the Fields of France, despite its English text, seems to belong to this group. The semi-recitative style and harmonic shifts suggest that White had kept up with such younger contemporaries as Bantock, or even Scott, and was prepared to use their techniques when appropriate. I have been unable to identify the author of this poem. The Irish Olympic runner Norman McEachern would be chronologically possible, though I find no indication that he was also a poet.

In some ways, the English songs are the most remarkable of all, since the other countries had well-established song traditions and repertoires upon which White could draw. England had the royalty ballad. Though White was slightly younger than Parry or Stanford, her earliest efforts are contemporary with theirs and show a fluidity of form they achieved only later. She can stand as a bridge between Cowen, who was tentatively renewing the ballad form, and Quilter, who much admired her work. In her most famous song, So we’ll go no more a roving and even more in How do I love thee? she preferred developing melodic lines to cut and dried “tunes”. In A Greeting she achieves a fine cumulative effect, contrasting with the intimacy of the Three Little Songs. If Absent yet Present is more regular in its movement, the vocal roulades of Ask Not lend an original touch to what might have been a tawdry ballad.

Christopher Howell

White was born in Dieppe on 23 June 1855 to English parents. The family moved to the UK before she reached the age of one. Aged seven, she spent two years in Heidelberg with her German governess, returning in 1864. The following year she was sent to school in Paris for three years, during which period her father died. Back in London, in 1868, she stayed with George Rose-Innes, a trustee of the White family who became something of a father figure. Rose-Innes, from Chile, enabled her to add Spanish to her store of languages and also introduced her to Italian opera, a potent melodic counterbalance to the strictly classical diet of her piano lessons up till that time. White published her first song in 1974. In 1874-5 she was in Torquay, where she took lessons in harmony and counterpoint from W.S. Rockstro, and in 1876 was admitted to the Royal Academy of Music, where she studied composition with Sir George Macfarren. In 1879 she became the first woman to obtain the Mendelssohn scholarship. In 1881, however, her mother died and White, distraught, abandoned the scholarship and went to Chile for ten months, where her sister was staying with the Rose-Innes family. Her return to London in 1882 coincided with the death of George Rose-Innes and she took a room on her own – a bold step for a woman in Victorian society.

White had by now a burgeoning portfolio of published compositions. The White family had been neither poor nor particularly wealthy and from now on she depended on her own efforts for an income – teaching piano if necessary, publishing songs and organizing concerts of her own music for preference. She also used her linguistic skills to translate books and poetry. Unlike many women song composers in the Victorian period, she remained unmarried – the nearest she came to a sentimental attachment, so far as is known, was her longstanding friendship with Robert Hichens (1864-1950), a homosexual writer and aesthete associated with Oscar Wilde and Alfred Douglas who introduced her to the beauties of Italy.

In 1883, White went to Vienna to study for six months with Robert Fuchs. Fuchs, and Macfarren before him, was concerned that White had written no large-scale works. Both tried to persuade her to write a piano concerto and both came to agree that songs and miniatures were her comfort zone. She did later attempt an opera (unfinished) and a ballet.

In her heyday, till the end of the century and, to some extent, until 1914, White enjoyed a high reputation and a more than adequate income on the strength of her compositions – enough to enable her to travel frequently. This was partly a matter of cultural curiosity, but ill-health increasingly obliged her to choose spa towns and places noted for their favourable climate. From 1901, encouraged by Hichens, she made Taormina, Sicily, her base, moving to Florence after the 1908 Messina earthquake. For a period, she was also in Rome, sharing accommodation with her sister. Her compositions petered out (the last was published in 1927) and, in the post-1918 world, she seemed a figure from the past. She published two volumes of memories and spent her last years in London, where she died in 1937.

The current interest in women composers has only marginally touched Maude Valérie White. Perhaps her almost exclusive output of songs is felt to play into the hands of those who dismiss Victorian women composers as the musical equivalent of the Victorian lady with her sketch book and amateur watercolours. Her one-time popularity, and even the name Maude, tempt commentators to include her in a blanket dismissal of female amateurs. This is grossly unfair. As seen above, White had a thorough professional training and, from approximately 1880 to 1914, supported herself almost exclusively through her compositions. Not many male composers managed this in those years. Above all, it is grossly unjust in view of the generally high standard and wide range of her songs. This latter point may arouse perplexity. White may seem a different composer according to the language she is setting – the five sung here are not the only ones. Is there a “real White” with a personal voice underlying this stylistic roving? Probably we need a fuller knowledge of her work to answer this.

Isaotta Blanzesmano, with its claustrophobic, decadent atmosphere and fragile longing, could easily have been written by Mascagni, a composer much associated with D’Annunzio. It also reveals White’s love of sweeping, arpeggiated chords, which lend sumptuousness even to her simplest accompaniments. The Canzoncina pastorale arrangement is a case in point. White also incorporated this melody in her piano suite From the Ionian Sea. Lullabies by Mary to the child Jesus are frequent in all Italian regions, but I have not identified the original of this one. Waiting, included in this group because of its Italian theme, combines two unrelated Tuscan Rispetti translated very freely by John Addington Symonds. White adheres more closely here to a traditional ballad form. The chattering accompaniment and brittle rhythms of the Serenata Española may be a reminder that White knew Spanish culture mainly by way of Chile. The text seems an essentially masculine one, but the score states that the song is for “baritone or mezzo-soprano”, thus authorizing the present performance.

The German Lieder, presumably products of White’s period of study with Fuchs in Vienna in 1883, were published between that year and 1885. Anybody coming to them blind might suppose them to be by Schumann – and worthy products of his pen. Closer examination will find the paradox that White has set, in four of the songs here, texts almost indelibly associated with Schumann, but treating them so differently as to imply a reproach to the German master. Ears accustomed to Dichterliebe – and what lover of Lieder is not? – will be startled to find Im wunderschönen Monat Mai not a dreamlike evocation of a time when the poet might still hope in requited love, but a sprightly expression of a young man’s aspirations. In the love-tangle of Ein Jüngling liebt ein Mädchen, Schumann’s folksy lilt implies this is the way of the world, we just have to put up with it, while White, perhaps taking the maiden’s part, adopts a doleful, almost tragic tone. In Hör’ ich das Liedchen klingen, Schumann strains his ear to hear the now distant melodies, while White takes her cue from Heine’s “stormy winds and rain”, which beat relentlessly throughout the song. It was presumably not White’s intention to create an “anti-Dichterliebe”. Rather, the two composers had different agendas. Schumann had strung together Heine’s miniatures to create a single narrative, giving them implied meanings in their new context that, as White readily spotted, they did not have when taken singly.

Of the other Lieder sung here, Schumann set just one – Stille Tränen. White replaces Schumann’s steadily pulsating accompaniment with a piano fantasy that the master would surely not have disowned. Die Himmelsaugen shows White’s ability to create a strikingly rich effect with the simplest means. This song might almost have been written by the young Richard Strauss. Das Meer hat seine Perlen, thanks to Longfellow’s rendering, is perhaps Heine’s most famous poem in the English-speaking world. It has been set by many composers, with general preference for an idyllic treatment. White opts for galloping passion.

Espoir en Dieu was one of White’s earliest successes. The model here may be Gounod. If White cannot quite achieve the fruity memorability of that master’s Repentir, she matches most of his other songs in religious vein. The later Si j’étais Dieu is closer to Fauré, though with an extra burst of passionate adrenalin. The other two songs in this group are much later and reflect White’s response to the Great War. Le depart du conscript, with a text by White herself, is a dialogue between the departing soldier and his sweetheart. The two never sing together and there is no indication that White intended it to be divided between two singers. The texture is more austere than in the earlier songs, creating a powerfully brooding atmosphere that saves the potentially mawkish sentimentality of the words. On the Fields of France, despite its English text, seems to belong to this group. The semi-recitative style and harmonic shifts suggest that White had kept up with such younger contemporaries as Bantock, or even Scott, and was prepared to use their techniques when appropriate. I have been unable to identify the author of this poem. The Irish Olympic runner Norman McEachern would be chronologically possible, though I find no indication that he was also a poet.

In some ways, the English songs are the most remarkable of all, since the other countries had well-established song traditions and repertoires upon which White could draw. England had the royalty ballad. Though White was slightly younger than Parry or Stanford, her earliest efforts are contemporary with theirs and show a fluidity of form they achieved only later. She can stand as a bridge between Cowen, who was tentatively renewing the ballad form, and Quilter, who much admired her work. In her most famous song, So we’ll go no more a roving and even more in How do I love thee? she preferred developing melodic lines to cut and dried “tunes”. In A Greeting she achieves a fine cumulative effect, contrasting with the intimacy of the Three Little Songs. If Absent yet Present is more regular in its movement, the vocal roulades of Ask Not lend an original touch to what might have been a tawdry ballad.

Christopher Howell

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads