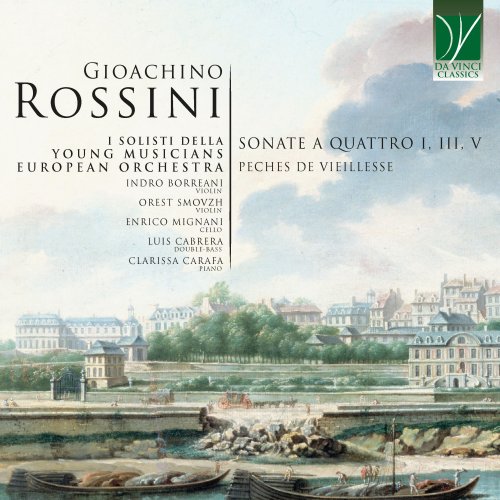

Clarissa Carafa, Enrico Mignani, Indro Borreani, Luis Cabrera, Orest Smovzh, Young Musicians European Orchestra - Gioachino Rossini: Sonatas for Four I, III, V | Peches de vieillesse (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Clarissa Carafa, Enrico Mignani, Indro Borreani, Luis Cabrera, Orest Smovzh, Young Musicians European Orchestra

- Title: Gioachino Rossini: Sonatas for Four I, III, V | Peches de vieillesse

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:09:54

- Total Size: 266 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Sonata I in G Major: I. Moderato

02. Sonata I in G Major: II. Andantino

03. Sonata I in G Major: III. Allegro

04. Sonata III in C Major: I. Allegro

05. Sonata III in C Major: II. Andante

06. Sonata III in C Major: III. Moderato

07. Sonata V in E-Flat Major: I. Allegro vivace

08. Sonata V in E-Flat Major: II. Andantino

09. Sonata V in E-Flat Major: III. Allegretto

10. Peches de vieillesse: No. 1 in D Major, Un mot à Paganini, élégie for Violin and Piano

11. Peches de vieillesse: No. 2 in A-Flat Major, Spécimen de mon temps

12. Peches de vieillesse: No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Spécimen de l'avenir

Music is an art of time; it is an art in time. Developing in time, it gives meaning to time. It represents a symbolic parallel to human life, to human stories, and to history. The harmonic and melodic tensions and resolutions it presents are symbolically understood and experienced as an icon of the hardships and joys of life, of its sometimes contradictory twists and turns, and of its orientation toward a goal (philosophers would say “of its teleology”). Music also transcends time and can offer experiences of eternity, of a time outside time. Furthermore, music extends beyond an individual’s life, allowing them to view, as it were, life “as” a piece of music.

This introduction seems well-suited, in my opinion, to the works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album. On one hand, they encompass virtually the whole of Rossini’s artistic life, which nearly coincides with his entire earthly life. On the other hand, some of these pieces offer insight into how Rossini himself viewed his own life and the “times” in which he lived.

When Gioachino Rossini was just twelve years old, he was invited to spend time during the summer holidays near Ravenna. He was a guest of Agostino Triossi, the landowner of a property called “Conventello.” Triossi was an enthusiastic amateur musician, surrounded by other equally passionate amateur musicians, and he delighted in the possibility of having the young musician at his estate, writing and playing with and for him.

Rossini would later recall that experience with his characteristic understatement, irony, and self-irony. He wrote on the set of parts, a manuscript collection copied by a hand other than his own: “Parts of First Violin, Second Violin, Cello, Double Bass. They refer to six horrible sonatas composed by me at the holiday place, near Ravenna, of my friend and patron, Agostino Triossi, at a most infantile age, without having received even a single course in accompaniment. All was composed and copied within three days and doggedly performed by Triossi on Double Bass, by Morini, his cousin, on First Violin, by the latter’s cousin on Cello, and by myself on Second Violin; and I was, to tell the truth, the least dogged.”

Today, this set of parts is housed at the Library of Congress in Washington; they are authenticated by Rossini’s ironic statement, which also suggests that he saw some merit in them.

And indeed, merit, or more than a little, is certainly to be found in these works. Formally, they are quite different from the Classical Sonatas as we know them—in the Viennese tradition developed by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. The themes are juxtaposed rather than developed; this may be due not only to Rossini’s comparative inexperience but also to his search for his own expressive vein and voice. Although these pieces are virtually the first complete works by Rossini that have reached us, they already display noteworthy maturity. Curiously, Rossini’s debut as a composer was in the field of instrumental music: while he is best known for his operas, instrumental music both opens and closes his artistic journey.

All sonatas are in three movements, in a style reminiscent of the Italian Baroque-rococo Concerto rather than the “German” Classical Sonata form. One of the most remarkable of the set is the last one, where Rossini showcases his precocious ability to build musical climaxes, presenting the listener with a vivid and poignant depiction of a storm.

Fast-forward many years later. Rossini had become one of the most celebrated operatic composers of his time, experiencing both unconditional success and criticism, acclaim, and failure. As is well known, at an age that today would be considered a man’s prime, he decided to stop composing operas and live a pleasant life in Paris. But is that the whole story? Certainly not. Firstly, he did not stop composing altogether; secondly, his life in Paris may have seemed outwardly pleasant, but it was not entirely so. He endured periods of intense depression, and his famous irony often served as a mask for an aching heart.

When asked about his decision, Rossini gave various answers. To Wagner, he said he had reached the age where “one does not compose anymore… one decomposes.” To his friend Andrea Maffei, he said, “Don’t you know that I am a great coward? I used to write operas when tunes would come to seek and seduce me, but when I understood that it was my job to go and seek them, being a lazy person, I renounced the journey and no longer wanted to write.” But Rossini’s truth, beyond this humor and irony, is revealed by another answer he gave to his friend Max Maria von Weber: “Don’t speak of this. Indeed, I am constantly composing. Do you see that bookshelf full of music? It has all been written after Guillaume Tell. But I am not publishing anything; I write because I cannot do otherwise.”

The outcome of this persistent, yet private work is gradually gaining recognition among musicologists and musicians. Full appreciation of Rossini’s late works has yet to be achieved, partly due to the extremely varied style and quality of his compositions. Many of them were compiled in the volumes of Péchés de vieillesse, or “Sins of Old Age.” However, these collections may give the impression of consistency and unity, while in fact, they contain very disparate works. Additionally, the titles given by Rossini can be misleading. Often, they are outright humorous, reflecting Rossini’s famous irony. However, it is debatable whether the music itself is as ironic as the titles imply or if it is, in fact, much more serious.

For instance, how should we interpret the homage to Paganini, Élegie, recorded here? Is it a parody of contemporary violinists’ mannerisms or a touching tribute to a departed friend? Paganini and Rossini were very close; indeed, in the famous painting by Josef Danhauser, Liszt at the Piano, they appear on the pianist’s left, with Rossini’s arm around Paganini, and the two figures looking as different as possible. Paganini was tall, very thin, with a sickly appearance contradicted by the fiery liveliness of his performances. Rossini, a bit shorter but decidedly plumper, had an air of bonhomie and kindness that was refreshing to see. In the 1830s, Paganini had asked Rossini to “write the Sonata based on the Romance from Otello and entitled Le Souvenir de Rossini à Paganini.” Rossini likely never fulfilled his friend’s request, but he somehow kept his promise by writing Un mot à Paganini several years after the Genoese violinist’s passing.

The two remaining pieces in this recording further exemplify how music can help make sense of time and its passage. They belong to a triptych found in the eighth volume of Péchés de vieillesse; accompanying them is a Spécimen de l’Ancien Régime, a sample of music from the past. In this piece, Rossini displayed—once more with his typical blend of irony and seriousness—his knowledge and appreciation of German music, such as that by Bach. While Rossini’s character and music may seem distant from Bach’s, there are many more points in common than one might assume. Indeed, Rossini’s interest in Bach’s works was such that he was nicknamed “Il Tedeschino,” or “the little German,” during his musical education. And if irony and humor are not lacking in Bach’s works (see the Coffee Cantata or the Fugue on the Chicken and Cuckoo!), neither is sacred inspiration absent from Rossini’s output (consider the Stabat Mater and Petite Messe Solennelle, to name two examples). Thus, when Rossini intended to parody “ancien régime” music, he could do so effectively both because he knew well the language and techniques of past music and because he genuinely loved it.

However, the two pieces recorded here represent music of Rossini’s time and music of the future. Here again, the line between parody and earnestness is difficult to define. At the very least, we must acknowledge Rossini’s ability to foresee some directions in future music, to the point that his skill in blending classical inspiration with innovative explorations of harmonic language has been compared, not without reason, to the later experiments of Sergei Prokofiev or Igor Stravinsky. Rossini almost bypassed Romanticism in its most languid and extreme aspects; he seemed to leap from Classicism to Neoclassicism. This is especially evident in the “music of the future” portrayed in the last piece recorded here.

Indeed, this work, almost a prophecy about future music, was evidently more than a joke for Rossini himself. In 1870, Francisco Hayez painted him holding a book with the words Musica dell’avvenire (“Music of the Future”). Against a black background, with only his face and hands illuminated, Rossini stands out in this somber depiction. Bach had himself portrayed holding a riddle canon; Rossini, with the “music of the future.” Far from being a stale conservative who had outlived his own music, Rossini was able to find in the past the roots of the future. To paraphrase Arnold Schoenberg’s praise of Brahms as “Brahms the Progressive,” we may indeed call Rossini “the progressive.” His Péchés reveal his personality and his deep reflection on his own time, on the times, and on where music was headed. From childhood’s carefree music to the bitter irony of his later years, the entire path of Rossini’s life is laid before us so that we may learn of him.

01. Sonata I in G Major: I. Moderato

02. Sonata I in G Major: II. Andantino

03. Sonata I in G Major: III. Allegro

04. Sonata III in C Major: I. Allegro

05. Sonata III in C Major: II. Andante

06. Sonata III in C Major: III. Moderato

07. Sonata V in E-Flat Major: I. Allegro vivace

08. Sonata V in E-Flat Major: II. Andantino

09. Sonata V in E-Flat Major: III. Allegretto

10. Peches de vieillesse: No. 1 in D Major, Un mot à Paganini, élégie for Violin and Piano

11. Peches de vieillesse: No. 2 in A-Flat Major, Spécimen de mon temps

12. Peches de vieillesse: No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Spécimen de l'avenir

Music is an art of time; it is an art in time. Developing in time, it gives meaning to time. It represents a symbolic parallel to human life, to human stories, and to history. The harmonic and melodic tensions and resolutions it presents are symbolically understood and experienced as an icon of the hardships and joys of life, of its sometimes contradictory twists and turns, and of its orientation toward a goal (philosophers would say “of its teleology”). Music also transcends time and can offer experiences of eternity, of a time outside time. Furthermore, music extends beyond an individual’s life, allowing them to view, as it were, life “as” a piece of music.

This introduction seems well-suited, in my opinion, to the works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album. On one hand, they encompass virtually the whole of Rossini’s artistic life, which nearly coincides with his entire earthly life. On the other hand, some of these pieces offer insight into how Rossini himself viewed his own life and the “times” in which he lived.

When Gioachino Rossini was just twelve years old, he was invited to spend time during the summer holidays near Ravenna. He was a guest of Agostino Triossi, the landowner of a property called “Conventello.” Triossi was an enthusiastic amateur musician, surrounded by other equally passionate amateur musicians, and he delighted in the possibility of having the young musician at his estate, writing and playing with and for him.

Rossini would later recall that experience with his characteristic understatement, irony, and self-irony. He wrote on the set of parts, a manuscript collection copied by a hand other than his own: “Parts of First Violin, Second Violin, Cello, Double Bass. They refer to six horrible sonatas composed by me at the holiday place, near Ravenna, of my friend and patron, Agostino Triossi, at a most infantile age, without having received even a single course in accompaniment. All was composed and copied within three days and doggedly performed by Triossi on Double Bass, by Morini, his cousin, on First Violin, by the latter’s cousin on Cello, and by myself on Second Violin; and I was, to tell the truth, the least dogged.”

Today, this set of parts is housed at the Library of Congress in Washington; they are authenticated by Rossini’s ironic statement, which also suggests that he saw some merit in them.

And indeed, merit, or more than a little, is certainly to be found in these works. Formally, they are quite different from the Classical Sonatas as we know them—in the Viennese tradition developed by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. The themes are juxtaposed rather than developed; this may be due not only to Rossini’s comparative inexperience but also to his search for his own expressive vein and voice. Although these pieces are virtually the first complete works by Rossini that have reached us, they already display noteworthy maturity. Curiously, Rossini’s debut as a composer was in the field of instrumental music: while he is best known for his operas, instrumental music both opens and closes his artistic journey.

All sonatas are in three movements, in a style reminiscent of the Italian Baroque-rococo Concerto rather than the “German” Classical Sonata form. One of the most remarkable of the set is the last one, where Rossini showcases his precocious ability to build musical climaxes, presenting the listener with a vivid and poignant depiction of a storm.

Fast-forward many years later. Rossini had become one of the most celebrated operatic composers of his time, experiencing both unconditional success and criticism, acclaim, and failure. As is well known, at an age that today would be considered a man’s prime, he decided to stop composing operas and live a pleasant life in Paris. But is that the whole story? Certainly not. Firstly, he did not stop composing altogether; secondly, his life in Paris may have seemed outwardly pleasant, but it was not entirely so. He endured periods of intense depression, and his famous irony often served as a mask for an aching heart.

When asked about his decision, Rossini gave various answers. To Wagner, he said he had reached the age where “one does not compose anymore… one decomposes.” To his friend Andrea Maffei, he said, “Don’t you know that I am a great coward? I used to write operas when tunes would come to seek and seduce me, but when I understood that it was my job to go and seek them, being a lazy person, I renounced the journey and no longer wanted to write.” But Rossini’s truth, beyond this humor and irony, is revealed by another answer he gave to his friend Max Maria von Weber: “Don’t speak of this. Indeed, I am constantly composing. Do you see that bookshelf full of music? It has all been written after Guillaume Tell. But I am not publishing anything; I write because I cannot do otherwise.”

The outcome of this persistent, yet private work is gradually gaining recognition among musicologists and musicians. Full appreciation of Rossini’s late works has yet to be achieved, partly due to the extremely varied style and quality of his compositions. Many of them were compiled in the volumes of Péchés de vieillesse, or “Sins of Old Age.” However, these collections may give the impression of consistency and unity, while in fact, they contain very disparate works. Additionally, the titles given by Rossini can be misleading. Often, they are outright humorous, reflecting Rossini’s famous irony. However, it is debatable whether the music itself is as ironic as the titles imply or if it is, in fact, much more serious.

For instance, how should we interpret the homage to Paganini, Élegie, recorded here? Is it a parody of contemporary violinists’ mannerisms or a touching tribute to a departed friend? Paganini and Rossini were very close; indeed, in the famous painting by Josef Danhauser, Liszt at the Piano, they appear on the pianist’s left, with Rossini’s arm around Paganini, and the two figures looking as different as possible. Paganini was tall, very thin, with a sickly appearance contradicted by the fiery liveliness of his performances. Rossini, a bit shorter but decidedly plumper, had an air of bonhomie and kindness that was refreshing to see. In the 1830s, Paganini had asked Rossini to “write the Sonata based on the Romance from Otello and entitled Le Souvenir de Rossini à Paganini.” Rossini likely never fulfilled his friend’s request, but he somehow kept his promise by writing Un mot à Paganini several years after the Genoese violinist’s passing.

The two remaining pieces in this recording further exemplify how music can help make sense of time and its passage. They belong to a triptych found in the eighth volume of Péchés de vieillesse; accompanying them is a Spécimen de l’Ancien Régime, a sample of music from the past. In this piece, Rossini displayed—once more with his typical blend of irony and seriousness—his knowledge and appreciation of German music, such as that by Bach. While Rossini’s character and music may seem distant from Bach’s, there are many more points in common than one might assume. Indeed, Rossini’s interest in Bach’s works was such that he was nicknamed “Il Tedeschino,” or “the little German,” during his musical education. And if irony and humor are not lacking in Bach’s works (see the Coffee Cantata or the Fugue on the Chicken and Cuckoo!), neither is sacred inspiration absent from Rossini’s output (consider the Stabat Mater and Petite Messe Solennelle, to name two examples). Thus, when Rossini intended to parody “ancien régime” music, he could do so effectively both because he knew well the language and techniques of past music and because he genuinely loved it.

However, the two pieces recorded here represent music of Rossini’s time and music of the future. Here again, the line between parody and earnestness is difficult to define. At the very least, we must acknowledge Rossini’s ability to foresee some directions in future music, to the point that his skill in blending classical inspiration with innovative explorations of harmonic language has been compared, not without reason, to the later experiments of Sergei Prokofiev or Igor Stravinsky. Rossini almost bypassed Romanticism in its most languid and extreme aspects; he seemed to leap from Classicism to Neoclassicism. This is especially evident in the “music of the future” portrayed in the last piece recorded here.

Indeed, this work, almost a prophecy about future music, was evidently more than a joke for Rossini himself. In 1870, Francisco Hayez painted him holding a book with the words Musica dell’avvenire (“Music of the Future”). Against a black background, with only his face and hands illuminated, Rossini stands out in this somber depiction. Bach had himself portrayed holding a riddle canon; Rossini, with the “music of the future.” Far from being a stale conservative who had outlived his own music, Rossini was able to find in the past the roots of the future. To paraphrase Arnold Schoenberg’s praise of Brahms as “Brahms the Progressive,” we may indeed call Rossini “the progressive.” His Péchés reveal his personality and his deep reflection on his own time, on the times, and on where music was headed. From childhood’s carefree music to the bitter irony of his later years, the entire path of Rossini’s life is laid before us so that we may learn of him.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads