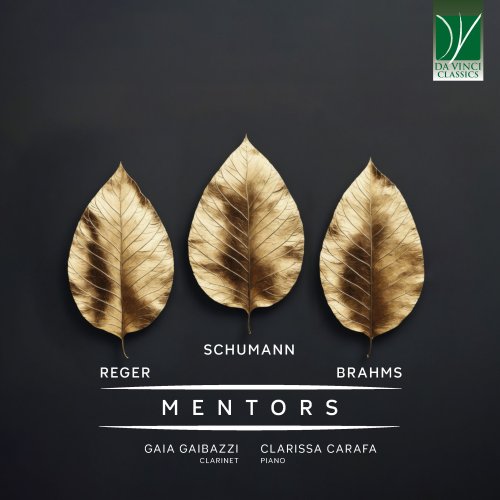

Gaia Gaibazzi, Clarissa Carafa - Max Reger, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms: Mentors (2025)

BAND/ARTIST: Gaia Gaibazzi, Clarissa Carafa

- Title: Max Reger, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms: Mentors

- Year Of Release: 2025

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:00:39

- Total Size: 229 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Albumblatt in E-Flat Major

02. Fantasiestücke für Klavier und Klarinette, Op. 73: No. 1, Zart und mit Ausdruck

03. Fantasiestücke für Klavier und Klarinette, Op. 73: No. 2, Lebhaft, leicht

04. Fantasiestücke für Klavier und Klarinette, Op. 73: No. 3, Rasch und mit Feuer

05. Tarantella in G Minor

06. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120: I. Allegro appassionato

07. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120: II. Andante un poco Adagio

08. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120: III. Allegretto grazioso

09. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120: IV. Vivace

10. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No.1 in A-Flat Major, Op. 49: I. Allegro affannato

11. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No.1 in A-Flat Major, Op. 49: II. Vivace, ma non troppo

12. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No.1 in A-Flat Major, Op. 49: III. Larghetto, ma non troppo, un poco con moto

13. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No.1 in A-Flat Major, Op. 49: IV. Prestissimo assai

Mentors and Muses:

The Cultural Interplay

of Schumann, Brahms, and Reger

Artists frequently seek mentors, navigating the intricate balance between inspiration and competition with their contemporaries and the great figures of the past. This relationship is vividly reflected in the evolution of musical forms, where composers engage in an ongoing dialogue with their predecessors, striving either to build upon or to challenge existing traditions. The works of Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, and Max Reger offer fascinating insights into how composers of the 19th and early 20th centuries reinterpreted and transformed the musical languages of their time.

Robert Schumann, a quintessential Romantic composer, was deeply influenced by the literary and philosophical movements of his era. His music often embodies the Romantic ideals of individualism, emotional depth, and the blurring of boundaries between music and other art forms, such as literature. Schumann’s fascination with the duality of the human psyche, his famous use of the alter egos Florestan and Eusebius, is mirrored in his compositions, which juxtapose contrasting moods and ideas within a unified structure. His innovative approach to form and content challenged the established norms of his time, paving the way for future composers to explore more personal and expressive forms of musical expression.

Johannes Brahms, who revered Schumann as both a mentor and a friend, represents a later stage in the Romantic tradition. Brahms’s music is often seen as a synthesis of classical form and Romantic expressiveness. Despite his deep respect for the past, especially the music of Bach, Beethoven, and Schubert, Brahms was not content to merely imitate his predecessors. Instead, he sought to infuse traditional forms, such as the sonata and the symphony, with a new level of emotional complexity and technical mastery. Brahms’s careful craftsmanship and rich harmonic language earned him a reputation as one of the greatest composers of his time, and his influence extended far beyond the Romantic period.

Max Reger, a composer of the late Romantic and early modern periods, was profoundly influenced by both Brahms and the earlier German tradition, including Bach. Reger’s music is characterized by its dense textures, intricate counterpoint, and bold harmonic language, reflecting his desire to combine the structural rigor of the Baroque and Classical eras with the chromaticism and emotional intensity of the late 19th century. Reger’s prolific output and his commitment to advancing the German musical tradition made him a key figure in the transition from Romanticism to modernism. His works, though rooted in tradition, often pushed the boundaries of tonality and form, anticipating the innovations of the 20th century.

The relationship between these three composers is emblematic of the broader cultural and artistic trends of their time. Schumann, Brahms, and Reger each sought to reconcile the heritage of the past with the demands of the present, creating music that is at once deeply rooted in tradition and boldly forward-looking. Their contributions to the clarinet and piano repertoire, in particular, have left a lasting impact, enriching the genre with works that are technically demanding and emotionally profound. These compositions continue to be central to the repertoire, inspiring performers and composers alike, and shaping the development of clarinet and piano music into the 20th century and beyond. Through their works, we can trace the evolution of Romanticism, the reassertion of classical forms, and the gradual emergence of modernist ideas that would shape the course of Western music.

Reger: Albumblatt (1902)

Max Reger’s Album Leaf in E-flat major is a charming and introspective piece that reflects his deep connection to the German Romantic tradition. Composed in 1902, this brief yet expressive work is a testament to Reger’s ability to convey profound emotion in a miniature form. The Album Leaf is often compared to the similar short-form works of composers like Schumann and Brahms, serving as a personal and intimate musical reflection. While not as technically demanding as some of Reger’s larger works, the Album Leaf is significant in the clarinet and piano repertoire for its lyrical qualities and the way it showcases the clarinet’s ability to sing in a warm, vocal style. This piece is particularly interesting for its subtle use of chromaticism and the way Reger weaves a delicate interplay between the clarinet and piano, creating a rich tapestry of sound despite its brevity. The Album Leaf can be seen as part of a broader tradition of such pieces that were often used as gifts or personal mementos, and while it may not be as famous as Reger’s larger works, it remains a delightful gem in the clarinet repertoire. Despite its brevity, Reger infused it with a harmonic richness that elevates it beyond simple background music, making it a reflective piece that captures the essence of Reger’s late-Romantic style.

Schumann: Fantasiestücke Op. 73 (1849)

Schumann’s Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73, composed in 1849, are among the most beloved works in the clarinet repertoire. These three pieces, Zart und mit Ausdruck (Tender and with Expression), Lebhaft, leicht (Lively, Light), and Rasch und mit Feuer (Quick and with Fire), were written during a period of intense creativity for Schumann, often referred to as his “chamber music year.” Zart und mit Ausdruck, the first piece, opens with a lyrical and introspective theme, showcasing the clarinet’s ability to convey tender emotion. This movement sets the tone for the entire set, emphasizing the intimate dialogue between the clarinet and piano. In Lebhaft, leicht, the mood shifts to a more playful and light-hearted character. Schumann’s intricate writing here demands precise articulation and a delicate touch, allowing the clarinet to dance gracefully over the piano’s accompaniment. The final piece, Rasch und mit Feuer, is the most virtuosic of the three. This piece in particular demonstrates Schumann’s skill in balancing the lyrical and the dramatic, a hallmark of his chamber music.

Reger: Tarantella (1902)

Reger’s Tarantella in G minor is a lively and spirited piece that draws on the traditional Italian dance form of the same name, known for its rapid tempo and rhythmic drive. Composed in 1902, this work exemplifies Reger’s interest in combining classical forms with the chromatic and harmonic innovations of his time. The Tarantella is particularly notable in the clarinet and piano repertoire for its technical demands and energetic character. The clarinet part requires agility and precision, with rapid passages and intricate rhythms that reflect the dance’s frenetic nature. Meanwhile, the piano provides a vibrant and equally challenging accompaniment, creating a dynamic interplay between the two instruments.

This piece is a wonderful example of how Reger could take a traditional form and infuse it with his own distinctive style. The Tarantella not only entertains with its vivacity but also challenges the performers to push the boundaries of their technical skills. This piece stands out in Reger’s oeuvre as it draws on an Italian dance form rather than the Germanic traditions he is typically associated with. This piece shows his willingness to explore beyond his cultural heritage, albeit through a distinctly Germanic lens.

Brahms: Sonata Op. 120 No. 1 (1894)

Johannes Brahms’s Sonata for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 120 No. 1 in F minor is a masterful work that stands as one of the great achievements in the clarinet repertoire. Composed in 1894 during the last years of Brahms’s life, this sonata, along with its companion piece, the Sonata No. 2 in E-flat major, was written for the clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld, whose playing Brahms greatly admired. The sonata opens with Allegro appassionato, a movement marked by its dramatic intensity and lyrical beauty. This movement sets the tone for the sonata, with its blend of passion and introspection. In the second movement, Andante un poco Adagio, Brahms creates a moment of serene beauty. The clarinet sings a long, flowing melody that is both tender and melancholic, revealing the composer’s deep sensitivity to the instrument’s expressive capabilities. This movement is often seen as the emotional heart of the sonata, offering a poignant contrast to the intensity of the first movement. The third movement, Allegretto grazioso, introduces a lighter, more playful character. Here, Brahms’s skill in writing elegant and charming melodies is on full display. The movement dances gracefully, providing a moment of relief before the sonata’s powerful finale.

The sonata concludes with Vivace, a movement filled with energy and rhythmic drive. Brahms uses complex rhythms and syncopations, creating a sense of urgency that propels the music forward to a thrilling conclusion. The sonata’s influence is evident in the subsequent development of the clarinet-piano duo repertoire, as it established a new standard for what could be accomplished with this type of ensemble.

Reger: Sonata Op. 49 No. 1 (1900)

Max Reger’s Sonata, Op. 49 No. 1 in A-flat major, composed in 1900, is a substantial and ambitious work that showcases the composer’s deep understanding of both the clarinet and piano. This sonata is one of Reger’s earlier compositions, yet it already demonstrates his distinctive style, characterized by rich harmonic language, intricate counterpoint, and a deep respect for classical forms. The sonata opens with Allegro affannato, a movement that immediately sets a serious and intense tone. The title, which means “agitated,” reflects the movement’s restless and searching character. The clarinet and piano engage in a complex dialogue, with the clarinet’s lyrical lines often weaving through the dense harmonic textures of the piano. In the second movement, Vivace, ma non troppo, Reger introduces a lighter, more rhythmically driven character. The movement is marked by its playful energy and intricate rhythms, providing a contrast to the intensity of the first movement. The third movement, Larghetto, ma non troppo, un poco con moto, offers a moment of reflection and lyricism. The clarinet’s long, flowing melodies are accompanied by a gently undulating piano part, creating a sense of calm and introspection. The sonata concludes with Prestissimo assai: the clarinet and piano engage in a rapid, almost breathless exchange of ideas, driving the music to a thrilling conclusion. Notable for its complex structure, the piece blends elements of sonata-allegro form with more free-flowing, rhapsodic passages. This approach reflects Reger’s deep understanding of classical forms while allowing him the freedom to explore new harmonic and thematic possibilities.

01. Albumblatt in E-Flat Major

02. Fantasiestücke für Klavier und Klarinette, Op. 73: No. 1, Zart und mit Ausdruck

03. Fantasiestücke für Klavier und Klarinette, Op. 73: No. 2, Lebhaft, leicht

04. Fantasiestücke für Klavier und Klarinette, Op. 73: No. 3, Rasch und mit Feuer

05. Tarantella in G Minor

06. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120: I. Allegro appassionato

07. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120: II. Andante un poco Adagio

08. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120: III. Allegretto grazioso

09. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120: IV. Vivace

10. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No.1 in A-Flat Major, Op. 49: I. Allegro affannato

11. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No.1 in A-Flat Major, Op. 49: II. Vivace, ma non troppo

12. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No.1 in A-Flat Major, Op. 49: III. Larghetto, ma non troppo, un poco con moto

13. Sonate für Klarinette und Klavier No.1 in A-Flat Major, Op. 49: IV. Prestissimo assai

Mentors and Muses:

The Cultural Interplay

of Schumann, Brahms, and Reger

Artists frequently seek mentors, navigating the intricate balance between inspiration and competition with their contemporaries and the great figures of the past. This relationship is vividly reflected in the evolution of musical forms, where composers engage in an ongoing dialogue with their predecessors, striving either to build upon or to challenge existing traditions. The works of Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, and Max Reger offer fascinating insights into how composers of the 19th and early 20th centuries reinterpreted and transformed the musical languages of their time.

Robert Schumann, a quintessential Romantic composer, was deeply influenced by the literary and philosophical movements of his era. His music often embodies the Romantic ideals of individualism, emotional depth, and the blurring of boundaries between music and other art forms, such as literature. Schumann’s fascination with the duality of the human psyche, his famous use of the alter egos Florestan and Eusebius, is mirrored in his compositions, which juxtapose contrasting moods and ideas within a unified structure. His innovative approach to form and content challenged the established norms of his time, paving the way for future composers to explore more personal and expressive forms of musical expression.

Johannes Brahms, who revered Schumann as both a mentor and a friend, represents a later stage in the Romantic tradition. Brahms’s music is often seen as a synthesis of classical form and Romantic expressiveness. Despite his deep respect for the past, especially the music of Bach, Beethoven, and Schubert, Brahms was not content to merely imitate his predecessors. Instead, he sought to infuse traditional forms, such as the sonata and the symphony, with a new level of emotional complexity and technical mastery. Brahms’s careful craftsmanship and rich harmonic language earned him a reputation as one of the greatest composers of his time, and his influence extended far beyond the Romantic period.

Max Reger, a composer of the late Romantic and early modern periods, was profoundly influenced by both Brahms and the earlier German tradition, including Bach. Reger’s music is characterized by its dense textures, intricate counterpoint, and bold harmonic language, reflecting his desire to combine the structural rigor of the Baroque and Classical eras with the chromaticism and emotional intensity of the late 19th century. Reger’s prolific output and his commitment to advancing the German musical tradition made him a key figure in the transition from Romanticism to modernism. His works, though rooted in tradition, often pushed the boundaries of tonality and form, anticipating the innovations of the 20th century.

The relationship between these three composers is emblematic of the broader cultural and artistic trends of their time. Schumann, Brahms, and Reger each sought to reconcile the heritage of the past with the demands of the present, creating music that is at once deeply rooted in tradition and boldly forward-looking. Their contributions to the clarinet and piano repertoire, in particular, have left a lasting impact, enriching the genre with works that are technically demanding and emotionally profound. These compositions continue to be central to the repertoire, inspiring performers and composers alike, and shaping the development of clarinet and piano music into the 20th century and beyond. Through their works, we can trace the evolution of Romanticism, the reassertion of classical forms, and the gradual emergence of modernist ideas that would shape the course of Western music.

Reger: Albumblatt (1902)

Max Reger’s Album Leaf in E-flat major is a charming and introspective piece that reflects his deep connection to the German Romantic tradition. Composed in 1902, this brief yet expressive work is a testament to Reger’s ability to convey profound emotion in a miniature form. The Album Leaf is often compared to the similar short-form works of composers like Schumann and Brahms, serving as a personal and intimate musical reflection. While not as technically demanding as some of Reger’s larger works, the Album Leaf is significant in the clarinet and piano repertoire for its lyrical qualities and the way it showcases the clarinet’s ability to sing in a warm, vocal style. This piece is particularly interesting for its subtle use of chromaticism and the way Reger weaves a delicate interplay between the clarinet and piano, creating a rich tapestry of sound despite its brevity. The Album Leaf can be seen as part of a broader tradition of such pieces that were often used as gifts or personal mementos, and while it may not be as famous as Reger’s larger works, it remains a delightful gem in the clarinet repertoire. Despite its brevity, Reger infused it with a harmonic richness that elevates it beyond simple background music, making it a reflective piece that captures the essence of Reger’s late-Romantic style.

Schumann: Fantasiestücke Op. 73 (1849)

Schumann’s Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73, composed in 1849, are among the most beloved works in the clarinet repertoire. These three pieces, Zart und mit Ausdruck (Tender and with Expression), Lebhaft, leicht (Lively, Light), and Rasch und mit Feuer (Quick and with Fire), were written during a period of intense creativity for Schumann, often referred to as his “chamber music year.” Zart und mit Ausdruck, the first piece, opens with a lyrical and introspective theme, showcasing the clarinet’s ability to convey tender emotion. This movement sets the tone for the entire set, emphasizing the intimate dialogue between the clarinet and piano. In Lebhaft, leicht, the mood shifts to a more playful and light-hearted character. Schumann’s intricate writing here demands precise articulation and a delicate touch, allowing the clarinet to dance gracefully over the piano’s accompaniment. The final piece, Rasch und mit Feuer, is the most virtuosic of the three. This piece in particular demonstrates Schumann’s skill in balancing the lyrical and the dramatic, a hallmark of his chamber music.

Reger: Tarantella (1902)

Reger’s Tarantella in G minor is a lively and spirited piece that draws on the traditional Italian dance form of the same name, known for its rapid tempo and rhythmic drive. Composed in 1902, this work exemplifies Reger’s interest in combining classical forms with the chromatic and harmonic innovations of his time. The Tarantella is particularly notable in the clarinet and piano repertoire for its technical demands and energetic character. The clarinet part requires agility and precision, with rapid passages and intricate rhythms that reflect the dance’s frenetic nature. Meanwhile, the piano provides a vibrant and equally challenging accompaniment, creating a dynamic interplay between the two instruments.

This piece is a wonderful example of how Reger could take a traditional form and infuse it with his own distinctive style. The Tarantella not only entertains with its vivacity but also challenges the performers to push the boundaries of their technical skills. This piece stands out in Reger’s oeuvre as it draws on an Italian dance form rather than the Germanic traditions he is typically associated with. This piece shows his willingness to explore beyond his cultural heritage, albeit through a distinctly Germanic lens.

Brahms: Sonata Op. 120 No. 1 (1894)

Johannes Brahms’s Sonata for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 120 No. 1 in F minor is a masterful work that stands as one of the great achievements in the clarinet repertoire. Composed in 1894 during the last years of Brahms’s life, this sonata, along with its companion piece, the Sonata No. 2 in E-flat major, was written for the clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld, whose playing Brahms greatly admired. The sonata opens with Allegro appassionato, a movement marked by its dramatic intensity and lyrical beauty. This movement sets the tone for the sonata, with its blend of passion and introspection. In the second movement, Andante un poco Adagio, Brahms creates a moment of serene beauty. The clarinet sings a long, flowing melody that is both tender and melancholic, revealing the composer’s deep sensitivity to the instrument’s expressive capabilities. This movement is often seen as the emotional heart of the sonata, offering a poignant contrast to the intensity of the first movement. The third movement, Allegretto grazioso, introduces a lighter, more playful character. Here, Brahms’s skill in writing elegant and charming melodies is on full display. The movement dances gracefully, providing a moment of relief before the sonata’s powerful finale.

The sonata concludes with Vivace, a movement filled with energy and rhythmic drive. Brahms uses complex rhythms and syncopations, creating a sense of urgency that propels the music forward to a thrilling conclusion. The sonata’s influence is evident in the subsequent development of the clarinet-piano duo repertoire, as it established a new standard for what could be accomplished with this type of ensemble.

Reger: Sonata Op. 49 No. 1 (1900)

Max Reger’s Sonata, Op. 49 No. 1 in A-flat major, composed in 1900, is a substantial and ambitious work that showcases the composer’s deep understanding of both the clarinet and piano. This sonata is one of Reger’s earlier compositions, yet it already demonstrates his distinctive style, characterized by rich harmonic language, intricate counterpoint, and a deep respect for classical forms. The sonata opens with Allegro affannato, a movement that immediately sets a serious and intense tone. The title, which means “agitated,” reflects the movement’s restless and searching character. The clarinet and piano engage in a complex dialogue, with the clarinet’s lyrical lines often weaving through the dense harmonic textures of the piano. In the second movement, Vivace, ma non troppo, Reger introduces a lighter, more rhythmically driven character. The movement is marked by its playful energy and intricate rhythms, providing a contrast to the intensity of the first movement. The third movement, Larghetto, ma non troppo, un poco con moto, offers a moment of reflection and lyricism. The clarinet’s long, flowing melodies are accompanied by a gently undulating piano part, creating a sense of calm and introspection. The sonata concludes with Prestissimo assai: the clarinet and piano engage in a rapid, almost breathless exchange of ideas, driving the music to a thrilling conclusion. Notable for its complex structure, the piece blends elements of sonata-allegro form with more free-flowing, rhapsodic passages. This approach reflects Reger’s deep understanding of classical forms while allowing him the freedom to explore new harmonic and thematic possibilities.

| Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads