This Da Vinci Classics album opens a window into the aural world of nineteenth-century Italy and France. Italy, to a higher extent; and France to a lesser point, but still very significantly, were countries where opera ruled in the musical world. There was also instrumental music, of course – especially in France; but, in the majority of cases, it depended in turn from operatic music.

Opera enthralled listeners of all ages and almost all cultural and social positions; it was a mass phenomenon, which involved not only those who could afford theatre tickets, but permeated the musical world at all levels. Those who could never have the means for actively participating in operatic performances were still very likely to hear the tunes from the most beloved contemporaneous operas.

These tunes were popularized in a number of ways. People sang operatic arias at home, in the taverns, in the streets and at work. (Anecdotally, as late as in the 1950s, my mother’s neighbour, who liked to drink with friends in the evenings, always came back home singing Verdi’s Arias. And it was a very popular neighbourhood). Hurdy-gurdys also played the best known and most beloved tunes at the crossroads or in the markets. In the concert halls and private salons, domestic music-making abundantly drew from that wellspring. Why was it so? Probably because listening to music (different from, for instance, watching movies or reading poetry) is an activity where repetition, and “what is known”, are positive and enjoyable elements, rather than something eliciting boredom. Furthermore, amateur musicians who played famous operatic tunes were somewhat relieved from the difficulty of deciphering a score, since they already knew the gist of it. At the other extreme of the musical spectrum, virtuoso players also performed many fantasies and potpourris on operatic themes. These were pieces with a pronounced improvisational character, in which – typically – cantabile sections where a famous aria’s theme was quoted almost verbatim alternated with brilliant passages. These could either be embellishments / variations of the theme, or unrelated with it. In this fashion, the virtuoso player who presented him- or herself on a city’s stage was virtually sure of a successful welcome. Their virtuosity would be acclaimed in the difficult passageworks; but the aridity which such exercise-like passages can cause would be compensated for by the delight of hearing a well-known and beloved tune.

There were still other phenomena connected with this musical worldview. One was that of public occasions and music-making: for instance, and especially in a country with pleasant weather such as Italy, marching bands (typically of winds) were particularly appreciated; there, too, arrangements or elaborations after operatic themes were in high demand. Even at church, where – in principle, and also according with official Church regulations – no operatic tunes should have been heard, in fact opera was able to infiltrate. Organists employed the rich arsenal and palette of timbral effects available on their instruments in order to perform colourful versions of the best loved arias of the era; at times, these were at least somewhat hidden into a tight compositional texture which made them less recognizable, whilst, at times, there was no attempt at concealing them whatsoever.

And then there was the dimension of chamber music, of collective music-making. This was a much beloved pastime, especially in some zones of Italy (for instance, those then belonging in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where ensemble music-making was highly valued). Members of the upper bourgeoisie – but also of the lower classes – liked to spend their free time playing and/or singing together. The easiest and most common way to enjoy operatic music at home, at a time when no means of artificial reproduction of sound were available (or they were expensive, or not commonly used), was to sing it. The piano was a common feature of many reading rooms, in homes of people from many different social classes. (Here again, our family saga includes a relative whose job was to sell vegetables and fruits; in the 1920s or so, he spent his Sunday afternoons playing string quartet with his friends). Singing arias and duets to the accompaniment of a piano was the most immediate option for those willing to enjoy opera at home.

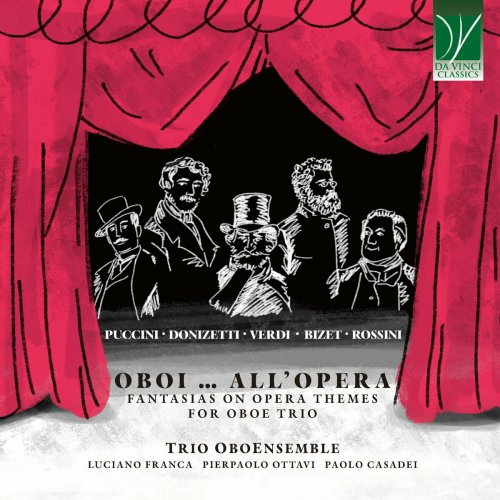

But some arias were too difficult for amateur singers; in that case, one could play the tune on other melodic instruments. This caused a proliferation of transcriptions and arrangements for the most varied kinds of ensembles, including the one represented in this Da Vinci Classics CD. Here the ensemble is, to be sure, not one of the commonest; the Oboe Trio constituted by two oboes and an English horn is relatively rare, even though its members could be found rather easily within those contexts where wind bands were common.

The programme performed here draws from those of the best loved among nineteenth-century Italian and French operas.

Il Barbiere di Siviglia is certainly one of the most appreciated comic operas of all times. Written by a very young Rossini, surprisingly it did not meet with immediate success. Only after a while did it start to become one of the milestones of Italian opera. The plot is well known, and derived from Beaumarchais’ trilogy. The Count of Almaviva is in love with Rosina, the young pupil of an old, strict man who would like, in turn, to marry her. Almaviva enlists the cooperation of his friend Figaro, a barber, in order to win Rosina’s heart; but, wishing to be sure that Rosina is in love with him and not with his title, Almaviva disguises himself as an ordinary youth, Lindoro. The plot advances by twists and turns, with unexpected incidents, brilliant ideas (mainly by Figaro and by Rosina herself), and chaotic situations whose eventual solution seems impossible before it is actually found. In this opera, pieces which have gained eternal glory are found: from the celebrated Overture – symbolizing also the impressive speed at which Rossini could compose – to Largo al factotum, many of its themes entered popular culture and steadily remained there.

A similar atmosphere of lightheartedness and genuine fun is found in Gaetano Donizetti’s Don Pasquale, another milestone of the comic opera repertoire. The protagonist, the elderly Don Pasquale, is the object of a ruthless plot, caused, in turn, by his avarice and strictness with his nephew Ernesto. Since Don Pasquale forbids Ernesto from marrying his beloved Norina, Norina herself is presented to Don Pasquale under a false name and identity. At first lovable, gentle, and remissive, Norina then shows herself to be a shrew as soon as Don Pasquale – who fell in love with her – gives her half his patrimony. The elderly gentleman is so relieved when he is informed that this insufferable woman is not attached to him, that he happily consents to her wedding with Ernesto.

In the case of Bizet’s Carmen, this album does not include a Fantasy or potpourri, but a selection after three of its instrumental movements. Carmen is unanimously considered as one of the most important French operas – ironically, since it represents, in collective imagination, Spain in its quintessence. France, indeed, has always been deeply fascinated by Spain, and countless French artists portrayed, in various forms, the picturesque and colourful world of their neighbours in the Iberian Peninsula. Carmen is the story of a woman with a very strong personality and of extreme beauty, who is loved by several men and knows how to play with their hearts. Scenes of unrequited love alternate with brilliant depictions of Spanish life (including the famous portraits of the corrida and of the world gravitating around the Plaza de toros), and the full palette of human feelings and sentiments finds its place in this justly famous opera.

Another complex woman is the protagonist of Giuseppe Verdi’s Traviata, in turn one of the best-known operas in the entire repertoire. Violetta is a young Parisian lady, who – similar to Carmen – is very beautiful and very popular among men. One of her admirers is young Alfredo Germont, who loves her passionately; for the first time, Violetta herself feels a deep and honest love for him, and considers this an opportunity for abandoning her dissolute lifestyle. However, Alfredo’s closeness to an adventuress as Violetta is harmful to the reputation of his sister, a very chaste young lady; thus, Alfredo’s father requires from Violetta that she distances herself from her beloved. This coincides with Violetta’s discovery of a fatal illness, tuberculosis; she is mistreated by Alfredo (who does not know the reasons for her behaviour) and only on her deathbed the honesty of her intentions is discovered. Here too the quantity of famous themes and arias is too large to list: from Libiamo to Parigi, o cara, from Di Provenza il mar, il suol to Sempre libera, to Addio del passato… few operas can claim so many immortal tunes.

Finally, Puccini’s Madama Butterfly concludes this promenade. Puccini was fascinated with the idea of tragical heroines, of women with a sad destiny and a complex personality. With Madama Butterfly he infused abundant exoticism into the world of Italian opera. The protagonist is a young geisha who has been left with a child, the son of an American officer, Pinkerton. Cio-Cio-San is convinced that she has been legally espoused by Pinkerton, but, in fact, he cheated on her. The discovery of his betrayal leads to the young lady’s tragical death.

In all of these cases, the oboes demonstrate their potential for singing, for evoking the timbre and colours of the human voice, and for brilliantly interacting with each other. The arrangements and adaptations performed here showcase the full potential of the oboe Trio for suggesting both the expressive, singing tone of belcanto singing, and the colourful orchestration of the operatic orchestra.

Chiara Bertoglio