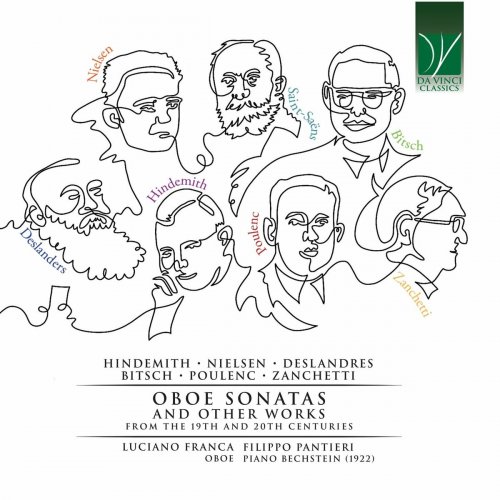

Luciano Franca - Hindemith, Nielsen, Deslandres, Bitsch, Poulenc, Zanchetti: Oboe Sonatas and Other Works from the 20th and 21st Centuries (2023)

BAND/ARTIST: Luciano Franca, Filippo Pantieri

- Title: Hindemith, Nielsen, Deslandres, Bitsch, Poulenc, Zanchetti: Oboe Sonatas and Other Works from the 20th and 21st Centuries

- Year Of Release: 2023

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 54:51 min

- Total Size: 175 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

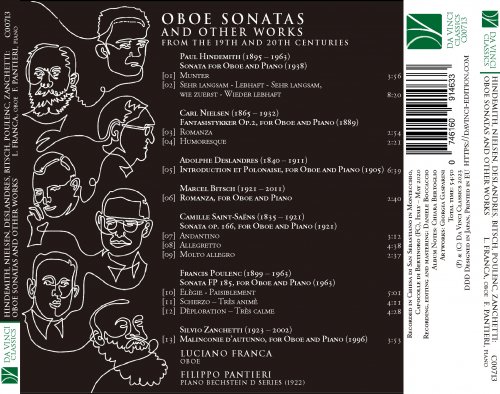

Tracklist:

01. Sonata: I. Munter (For Oboe and Piano)

02. Sonata: II. Sehr langsam - Lebhaft - Sehr langsam, wie zuerst - Wieder lebhaft (For Oboe and Piano)

03. Fantasistykker, Op. 2: I. Romanza (For Oboe and Piano)

04. Fantasistykker, Op. 2: II. Humoresque (For Oboe and Piano)

05. Introduction et Polonaise (For Oboe and Piano)

06. Romanza (For Oboe and Piano)

07. Sonata for Oboe and Piano in D Major, Op. 166: I. Andantino

08. Sonata for Oboe and Piano in D Major, Op. 166: II. Allegretto

09. Sonata for Oboe and Piano in D Major, Op. 166: III. Molto allegro

10. Sonata for Oboe and Piano, FP 185: I. Elègie - Paisiblement (For Oboe and Piano)

11. Sonata for Oboe and Piano, FP 185: II. Scherzo – Très animè (For Oboe and Piano)

12. Sonata for Oboe and Piano, FP 185: III. Dèploration – Très calme (For Oboe and Piano)

13. Malinconie d’autunno (For Oboe and Piano)

This Da Vinci Classics album is valuable not only for the beautiful works it comprises, for the variety of the programme and for the balance between major works from the repertoire and lesser-known gems, but also for the sound it proposes. The dialogue between oboe and piano, in fact, is established here with a very special partner to the wind instrument. The piano is a historical instrument built in 1922, practically one century ago. And, interestingly, two of the featured composers were born around that same year (Bitsch in 1921, and Zanchetti in 1923), while Saint-Saëns had died the year before (1921). The lives of all other artists, with the only exception of Deslandres, spanned over that fateful year 1922. It works, therefore, in the fashion of a pivot or a pillar, as the center of concentric circles focusing all around it.

That year, in fact, is no mere coincidence. It represents a particular moment for music history. A moment framed by the two World Wars, in the Roaring Twenties, and when new musical idioms were establishing themselves over the ruins of a world whose last remnants had been disintegrated by the War. The provocations of jazz on the one hand; the dissolution of tonality in Vienna (with serialism and dodecaphony) and in Paris (with modality and the emptying of traditional harmony) on the other hand; all this, and much more, concurred in establishing new canons, new parameters, new perspectives. Some of them were desolate and mirrored the despair and loss of reference points experimented by many at that time; others were more proactive and positive, seeing the post-War experience as an opportunity for new creations and experimentalism.

The pianos built at that time do not differ substantially from today’s pianos; no major technical improvement or change has been introduced in piano building since the late nineteenth century. However, the sound of a historical piano such as the Bechstein played here and that of a contemporary piano is undeniably different. This is due to minor differences in the process of instrument building, to the materials originally employed, and to the ageing of those same materials. Doubtlessly, an instrument such as that played here is not a standard instrument; it was designed with the specific purpose of aiming at the highest levels of craftmanship. With instruments of this value, their beauty may increase with time, rather than decrease, even though pianos, different from violins, tend to lose their best qualities as years go by.

Particularly in the interaction with a wind instrument such as an oboe, though, the contribution of an instrument such as this Bechstein is invaluable. The mellow, round tone of these comparatively ancient instruments blends wonderfully with the oboe’s timbre; also on the plane of volume, an ideal balance is more easily achieved. It mirrors, moreover, the sound with which many composers represented here would have been familiar, and the sound they could have pursued as their own aesthetic ideal when composing many of the pieces recorded here.

The repertoire played in this album consists of some important Sonatas from the twentieth-century repertoire, and some shorter pieces. The genre of the Sonata for winds and piano had become rather popular in the Romantic era, but seemed to frighten later composers, who only reluctantly came to the resolution of writing one or more. The only major exception is represented by French composers of the twentieth century, who seemed not to have been worried by the genre’s majestic and imposing tradition. The weight of that tradition, by way of contrast, was felt more intensely by those steeped in the Austro-German school, which had brought the classical Sonata form to its perfection but also undermined it.

Within this framework, therefore, Paul Hindemith constitutes a notable exception. A quintessential representative of that tradition, who deliberately subsumed the perspectives and techniques of the past (with particular attention to Bachian counterpoint), Hindemith did not eschew the challenge of the Sonata. Indeed, he dived into that challenge headfirst, composing some 26 Sonatas for virtually all instruments of the symphonic orchestra, and thus contributing substantially to the solo and chamber music repertoire. As concerns his output for winds and piano, he wrote no less than ten Sonatas for one wind instrument and piano between 1936 and 1955. These can be grouped into three categories, chronologically divided. A first group comprises the six works written by Hindemith in the late Thirties, just prior to leaving Germany due to his dissent against the Nazi regime. The Oboe Sonata recorded here belongs in this group, since it was composed, together with that for bassoon, in 1938. A second group is that of the Sonatas written in the early years of his American period; the third group consists of the single Tuba Sonata, written in 1955 when Hindemith came back to Europe.

All of these Sonatas are challenging both on the compositional and on the performing plane. Hindemith considered this project as an exploration of musical genres and techniques, and also of how a same instrument (the piano) could find new kinds of balance when interacting with instruments whose characterizing features are as different as possible (one has just to compare a flute with a tuba to imagine how complex this balance can be). However, a trait which often appears in Hindemith’s Sonatas is a tendency to write in three-part counterpoint, somehow in the style of Bach’s Sonatas for violin or gamba and harpsichord, with two parts entrusted to the pianists’ hands and one to the wind instrument.

The Sonata recorded here was written in parallel with the score for a ballet by the name of Nobilissima visione, dedicated to St. Francis of Assisi; the two works, in spite of their diversity, have several elements in common.

Hindemith’s Oboe Sonata opens with a first movement in a revised version of the traditional Sonata form, interpreted with Hindemith’s modern eyes. It is characterized by a purposefully goofy melody, which may recall the idea of a “bear dance”; the second theme is, by way of contrast, deeply expressive. The second movement is finely structured, with the intertwining of alternating and contrasting sections, capped by a concluding Coda with an intense recitativo; contrapuntal and fugato elements are not missing. This movement thus seems to resume, in itself, the traditional slow movement and the scherzo. This Sonata was premiered by Léon Goossens and Harriet Cohen on July 27th, 1938, in London, a few days after the premiere of Nobilissima visione.

The atmospheres conjured up in Carl Nielsen’s Fantasistykker (“Fantasy Pieces”) for oboe and piano are unambiguously different from those in Hindemith’s Sonata. This pair of pieces, in fact, predates Hindemith’s work by nearly fifty years, and mirrors a very different outlook on music and on society. They express their young composer’s fresh inspiration and bespeak a still deeply Romantic worldview. Nielsen himself described them as follows: “The two oboe pieces are a very early opus. The first — slow — piece gives the oboe the opportunity to sing out its notes quite as beautifully as this instrument can. The second is more humorous, roguish, with an undertone of Nordic nature and forest rustlings in the moonlight”.

Their genesis was not straightforward; the first piece was originally conceived for oboe and organ, and both works were subject to revisions, also following a discussion with Orla Rosenhoff, Nielsen’s former Conservatory teacher; moreover, the Humoresque was originally titled “Intermezzo”. Still, the pieces obtained great success by public and press, when they were premiered at the Royal Orchestra Soirées in Copenhagen on March 16th, 1891, with Olivo Krause and Victor Bendix. Such was the pieces’ charm that Hans Sitt transcribed the first of them for violin and orchestra, in a version which would be performed by the composer himself.

The composition of Adolphe Deslandres’ Introduction and Polonaise took place halfway through that of the works hitherto discussed. It was written as one of the many beautiful “Morceaux de concours”, commissioned by the Conservatoire of Paris year after year as compulsory pieces for the final examinations. Deslandres’ piece, which allows candidates and accomplished performers alike to showcase their technical and musical prowess, was employed in the examinations of 1905 and is dedicated to Théodore Dubois, who was the Conservatory’s Director at the time.

Another Parisian composer, with important ties to the Conservatory, was Marcel Bitsch, who studied and taught there for nearly three decades. His large output, comprising many symphonic works and several pieces demonstrating his full mastery of the performing techniques of wind instruments, also includes important theoretical works, particularly on counterpoint and polyphony. His Romanza can be interestingly compared with Nielsen’s: in spite of the obvious stylistic differences, some common traits do not fail to appear here and there.

Similar to Hindemith, although with a completely different musical, stylistic and aesthetical approach, also Saint-Saëns engaged systematically in the composition of Sonatas for solo instruments and piano. A splendid output of Sonatas came about in the composer’s last years; the Oboe Sonata, in particular, was written in the very same year of his death. This self-appointed task was understood by the composer as a mission: “At the moment I am concentrating my last reserves on giving rarely considered instruments the chance to be heard”, he wrote to Jean Chantavoine in Spring 1921. Dedicated to the principal oboe of the Société du Conservatoire de l’Opéra, Louis Bas, the Sonata comprises three movements. The first of them is reminiscent of the Baroque and Classical “Siciliana”. The second movement has a rhapsodic quality; its scoring recalls the “musettes”, and its freer sections offer abundant opportunities for unrestrained expression. The finale, as frequently happens with Saint-Saëns, is a triumph of brilliancy and virtuosity, of good humour and of special effects. Painstakingly attentive to the detail until his last moments, Saint-Saëns rehearsed this Sonatas and its twins before having it printed; the first run-through of this one took place on June 21st, with Louis Bas. Seemingly, no substantial corrections were made; satisfied, Saint-Saëns reported that the rehearsal “went like clockwork”.

Forty years later (1962), another Frenchman, Francis Poulenc, whose musical outlook has many points in common with Saint-Saëns, wrote his own Sonata; in turn, this was to be one of his last works. Written as a tribute to the memory of Sergei Prokofjev, it expresses the grieving process in music. The opening movement, a touching Elegie, begins with an oboe solo which poignantly transmits the survivor’s loneliness. By way of contrast, the joyful Scherzo pays homage to Prokofjev’s most brilliant creations and to the distinguishing traits of Poulenc’s own style. The Finale, Déploration, is the impressive juxtaposition of these two extremely different expressive and affective worlds, recalling the complexity of our human emotions. The music is pervaded by a sense of deep calm, as if it were an almost farewell.

Zanchetti’s Malinconie d’autunno, dedicated to the Duo Franca-Panteri, which concludes the CD, calls once more on the oboe’s expressive power and on its capability to evoke nostalgia, melancholy and the common associations with the golden and reddish tinges of autumn leaves.

Together, these works build up the full palette of the oboe’s expressive nuances, and highlight the piano’s – and particularly the historical piano’s – capability to move with its tone alone.

Chiara Bertoglio

That year, in fact, is no mere coincidence. It represents a particular moment for music history. A moment framed by the two World Wars, in the Roaring Twenties, and when new musical idioms were establishing themselves over the ruins of a world whose last remnants had been disintegrated by the War. The provocations of jazz on the one hand; the dissolution of tonality in Vienna (with serialism and dodecaphony) and in Paris (with modality and the emptying of traditional harmony) on the other hand; all this, and much more, concurred in establishing new canons, new parameters, new perspectives. Some of them were desolate and mirrored the despair and loss of reference points experimented by many at that time; others were more proactive and positive, seeing the post-War experience as an opportunity for new creations and experimentalism.

The pianos built at that time do not differ substantially from today’s pianos; no major technical improvement or change has been introduced in piano building since the late nineteenth century. However, the sound of a historical piano such as the Bechstein played here and that of a contemporary piano is undeniably different. This is due to minor differences in the process of instrument building, to the materials originally employed, and to the ageing of those same materials. Doubtlessly, an instrument such as that played here is not a standard instrument; it was designed with the specific purpose of aiming at the highest levels of craftmanship. With instruments of this value, their beauty may increase with time, rather than decrease, even though pianos, different from violins, tend to lose their best qualities as years go by.

Particularly in the interaction with a wind instrument such as an oboe, though, the contribution of an instrument such as this Bechstein is invaluable. The mellow, round tone of these comparatively ancient instruments blends wonderfully with the oboe’s timbre; also on the plane of volume, an ideal balance is more easily achieved. It mirrors, moreover, the sound with which many composers represented here would have been familiar, and the sound they could have pursued as their own aesthetic ideal when composing many of the pieces recorded here.

The repertoire played in this album consists of some important Sonatas from the twentieth-century repertoire, and some shorter pieces. The genre of the Sonata for winds and piano had become rather popular in the Romantic era, but seemed to frighten later composers, who only reluctantly came to the resolution of writing one or more. The only major exception is represented by French composers of the twentieth century, who seemed not to have been worried by the genre’s majestic and imposing tradition. The weight of that tradition, by way of contrast, was felt more intensely by those steeped in the Austro-German school, which had brought the classical Sonata form to its perfection but also undermined it.

Within this framework, therefore, Paul Hindemith constitutes a notable exception. A quintessential representative of that tradition, who deliberately subsumed the perspectives and techniques of the past (with particular attention to Bachian counterpoint), Hindemith did not eschew the challenge of the Sonata. Indeed, he dived into that challenge headfirst, composing some 26 Sonatas for virtually all instruments of the symphonic orchestra, and thus contributing substantially to the solo and chamber music repertoire. As concerns his output for winds and piano, he wrote no less than ten Sonatas for one wind instrument and piano between 1936 and 1955. These can be grouped into three categories, chronologically divided. A first group comprises the six works written by Hindemith in the late Thirties, just prior to leaving Germany due to his dissent against the Nazi regime. The Oboe Sonata recorded here belongs in this group, since it was composed, together with that for bassoon, in 1938. A second group is that of the Sonatas written in the early years of his American period; the third group consists of the single Tuba Sonata, written in 1955 when Hindemith came back to Europe.

All of these Sonatas are challenging both on the compositional and on the performing plane. Hindemith considered this project as an exploration of musical genres and techniques, and also of how a same instrument (the piano) could find new kinds of balance when interacting with instruments whose characterizing features are as different as possible (one has just to compare a flute with a tuba to imagine how complex this balance can be). However, a trait which often appears in Hindemith’s Sonatas is a tendency to write in three-part counterpoint, somehow in the style of Bach’s Sonatas for violin or gamba and harpsichord, with two parts entrusted to the pianists’ hands and one to the wind instrument.

The Sonata recorded here was written in parallel with the score for a ballet by the name of Nobilissima visione, dedicated to St. Francis of Assisi; the two works, in spite of their diversity, have several elements in common.

Hindemith’s Oboe Sonata opens with a first movement in a revised version of the traditional Sonata form, interpreted with Hindemith’s modern eyes. It is characterized by a purposefully goofy melody, which may recall the idea of a “bear dance”; the second theme is, by way of contrast, deeply expressive. The second movement is finely structured, with the intertwining of alternating and contrasting sections, capped by a concluding Coda with an intense recitativo; contrapuntal and fugato elements are not missing. This movement thus seems to resume, in itself, the traditional slow movement and the scherzo. This Sonata was premiered by Léon Goossens and Harriet Cohen on July 27th, 1938, in London, a few days after the premiere of Nobilissima visione.

The atmospheres conjured up in Carl Nielsen’s Fantasistykker (“Fantasy Pieces”) for oboe and piano are unambiguously different from those in Hindemith’s Sonata. This pair of pieces, in fact, predates Hindemith’s work by nearly fifty years, and mirrors a very different outlook on music and on society. They express their young composer’s fresh inspiration and bespeak a still deeply Romantic worldview. Nielsen himself described them as follows: “The two oboe pieces are a very early opus. The first — slow — piece gives the oboe the opportunity to sing out its notes quite as beautifully as this instrument can. The second is more humorous, roguish, with an undertone of Nordic nature and forest rustlings in the moonlight”.

Their genesis was not straightforward; the first piece was originally conceived for oboe and organ, and both works were subject to revisions, also following a discussion with Orla Rosenhoff, Nielsen’s former Conservatory teacher; moreover, the Humoresque was originally titled “Intermezzo”. Still, the pieces obtained great success by public and press, when they were premiered at the Royal Orchestra Soirées in Copenhagen on March 16th, 1891, with Olivo Krause and Victor Bendix. Such was the pieces’ charm that Hans Sitt transcribed the first of them for violin and orchestra, in a version which would be performed by the composer himself.

The composition of Adolphe Deslandres’ Introduction and Polonaise took place halfway through that of the works hitherto discussed. It was written as one of the many beautiful “Morceaux de concours”, commissioned by the Conservatoire of Paris year after year as compulsory pieces for the final examinations. Deslandres’ piece, which allows candidates and accomplished performers alike to showcase their technical and musical prowess, was employed in the examinations of 1905 and is dedicated to Théodore Dubois, who was the Conservatory’s Director at the time.

Another Parisian composer, with important ties to the Conservatory, was Marcel Bitsch, who studied and taught there for nearly three decades. His large output, comprising many symphonic works and several pieces demonstrating his full mastery of the performing techniques of wind instruments, also includes important theoretical works, particularly on counterpoint and polyphony. His Romanza can be interestingly compared with Nielsen’s: in spite of the obvious stylistic differences, some common traits do not fail to appear here and there.

Similar to Hindemith, although with a completely different musical, stylistic and aesthetical approach, also Saint-Saëns engaged systematically in the composition of Sonatas for solo instruments and piano. A splendid output of Sonatas came about in the composer’s last years; the Oboe Sonata, in particular, was written in the very same year of his death. This self-appointed task was understood by the composer as a mission: “At the moment I am concentrating my last reserves on giving rarely considered instruments the chance to be heard”, he wrote to Jean Chantavoine in Spring 1921. Dedicated to the principal oboe of the Société du Conservatoire de l’Opéra, Louis Bas, the Sonata comprises three movements. The first of them is reminiscent of the Baroque and Classical “Siciliana”. The second movement has a rhapsodic quality; its scoring recalls the “musettes”, and its freer sections offer abundant opportunities for unrestrained expression. The finale, as frequently happens with Saint-Saëns, is a triumph of brilliancy and virtuosity, of good humour and of special effects. Painstakingly attentive to the detail until his last moments, Saint-Saëns rehearsed this Sonatas and its twins before having it printed; the first run-through of this one took place on June 21st, with Louis Bas. Seemingly, no substantial corrections were made; satisfied, Saint-Saëns reported that the rehearsal “went like clockwork”.

Forty years later (1962), another Frenchman, Francis Poulenc, whose musical outlook has many points in common with Saint-Saëns, wrote his own Sonata; in turn, this was to be one of his last works. Written as a tribute to the memory of Sergei Prokofjev, it expresses the grieving process in music. The opening movement, a touching Elegie, begins with an oboe solo which poignantly transmits the survivor’s loneliness. By way of contrast, the joyful Scherzo pays homage to Prokofjev’s most brilliant creations and to the distinguishing traits of Poulenc’s own style. The Finale, Déploration, is the impressive juxtaposition of these two extremely different expressive and affective worlds, recalling the complexity of our human emotions. The music is pervaded by a sense of deep calm, as if it were an almost farewell.

Zanchetti’s Malinconie d’autunno, dedicated to the Duo Franca-Panteri, which concludes the CD, calls once more on the oboe’s expressive power and on its capability to evoke nostalgia, melancholy and the common associations with the golden and reddish tinges of autumn leaves.

Together, these works build up the full palette of the oboe’s expressive nuances, and highlight the piano’s – and particularly the historical piano’s – capability to move with its tone alone.

Chiara Bertoglio

Year 2023 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads