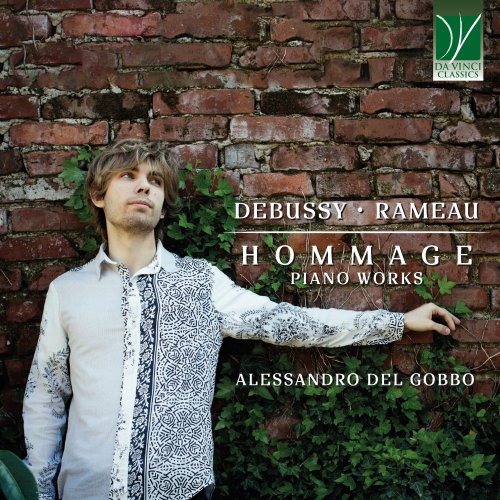

Alessandro Del Gobbo - Claude Debussy, Jean-Philippe Rameau: Hommage, Piano Works (2024)

BAND/ARTIST: Alessandro Del Gobbo

- Title: Claude Debussy, Jean-Philippe Rameau: Hommage, Piano Works

- Year Of Release: 2024

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:58:03

- Total Size: 174 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Pour le Piano: I. Prélude

02. Pour le Piano: II. Sarabande

03. Pour le Piano: III. Toccata

04. from Suite en Sol, RCT 6: Les Sauvages

05. from Suite en Sol, RCT 6: Les Tricotets

06. Hommage à Rameau: /

07. from Suite en Sol, RCT 6: L’Enharmonique

08. from Suite en Sol, RCT 6: L’Egyptienne

09. Suite Bergamasque: I. Prélude

10. Suite Bergamasque: II. Menuet

11. Suite Bergamasque: III. Clair de Lune

12. Suite Bergamasque: IV. Passepied

13. from Suite en Ré, RCT 3: Les Tendres Plaintes

14. from Suite en Ré, RCT 3: La Joyeuse

15. from Suite en Ré, RCT 3: La Follette

16. from Suite en Ré, RCT 3: Les Cyclopes

Is there anything like a “national style” in music? This is a thorny question, and one invested with very sensitive political aspects which can undermine from the outset every attempt at an honest answer. In literature, of course, the use of a certain language creates a kinship among its speakers. Even though there is a world of difference between – say – Flaubert and Sartre, or Hugo and Rabelais, still there is a common ground, a forma mentis, a shared background which ensures a certain degree of continuity. A language creates attitudes, forms of thought; they are not the only or the essential component of affinity, but certainly they are not to be dismissed lightly. It is certainly possible to say that Dostoevsky and Hugo are closer to each other than Hugo and Rabelais; still, the net of influences is so deep and structural that, possibly, there would have been no Hugo without Rabelais. Furthermore, there are nature and culture beside language, and even though culture evolves in turn (and so do, within limits, both landscapes and natural aspects), still people who were born in the same country will have a shared background with their fellow citizens.

To evoke a “national style” in music, as previously said, is riskier. The ghosts of nationalism show themselves easily, stereotypes abound, and the definition of what could count as “national” is frequently polluted by assessment of quality and value. Yet, if it is true that (possibly) there would have been no Hugo without a Rabelais, as different as these two authors may be, it is also true that there would have (possibly) been no Debussy and no Ravel without Rameau and Couperin. From a certain viewpoint, there is as huge and wide a difference between Debussy and Rameau as between Rabelais and Hugo. Debussy is normally labelled as the representative of musical “Impressionism”. The qualities associated with Impressionism in the visual arts are, among others, the abolition of contour and the use of juxtapositions of colours to create a “vibration”, an effect of indefiniteness similar to that of light in real life. In music, this translates in the acceptability of the juxtaposition and even superimposition of different, discordant harmonies. On the piano, a time-honoured dogma is subverted: “changing the pedal with each new harmony”, in order to keep each and every harmony “pure”, is no more a prescription. Once-incompatible harmonies can now resound together, creating a “vibration” of sound which parallels Monet’s enchanting effects of water and light. Rameau wrote for the harpsichord, where the entire concept of piano pedalling is entirely alien.

On the piano, the right pedal lifts the whole array of the dampers, which normally lie on the strings preventing them from vibrating. When the dampers are lifted, all strings become capable of resonating; those which have been hit by the hammers will keep vibrating until the phenomenon ceases naturally (or until the pedal is released and the dampers fall down again), but also the others will be called to vibration by the phenomenon of sympathetic resonance. On the harpsichord, there is no need for the pedal, because the plucked strings’ natural resonance is much lighter and much shorter than that of the piano. The pedal would not make any significant difference. Thus, even though there doubtlessly are sympathetic resonances on the harpsichord, this instrument is generally seen as the prototype of cleanness, transparency, neat lines and clear contours.

From this viewpoint, therefore, there is little if any contact between Rameau and Debussy. But, going beyond the surface of things, there is a whole world of common traits, or, at least, of possible influences. First and foremost, Debussy himself acknowledged the importance of Rameau for French music and for his own style. Debussy cannot be defined as a representative of musical nationalism in the same fashion as, for instance, Sibelius for Finland or Mussorgsky for Russia. However, Debussy’s reaction against musical Romanticism was also (doubtlessly) a reaction against Germany, where musical Romanticism had flourished most. And, even though Debussy was a great admirer of Bach, he was also keen on promoting French Baroque music, and claiming for it the status of “classic” which seemed to be due only to the German Baroque.

Second, the label of “Impressionist” does certainly apply to some works by Debussy (such as, for instance, La Cathédrale engloutie or Poissons d’or), but by no means to all. Other of his works are distinctly symbolist (typically Pelléas et Mélisande), but there is also a Neoclassical stream in his output – one which predates musical Neoclassicism proper. One could arguably say that there are at least as many piano works by Debussy where lines are clearly cut and colours sharply opposed as works with nuances of sound and timbre and the suppression of harmonic “contours”.

Furthermore (and without, of course, any pretense to exhaust the subject!) there is the fascination of both composers for music inspired by visual impressions or extramusical promptings. Rameau, following a tradition which was not exclusive for France, but certainly deeply rooted in his country, used to label many of the pieces constituting his Suites with descriptive titles. These could, at times, refer directly and patently to some aspects of musical descriptivism (such as birdsong, for instance); at times, the nexus is harder to grasp, especially without some kind of musicological background.

In 1725, two “savages” (as the American natives were, alas, disparagingly labelled at the time) were brought from Louisiana to Paris, and they performed a warrior dance in various venues, including the Theatre of the Italian Comedy. Their performance impressed the audience enormously, although with varying degrees of enthusiasm. Rameau was fascinated by the exoticism of what he saw and heard: and this, in turn, is something that unites Rameau with Debussy, whose musical style was deeply influenced by the “exotic” music he heard at the Universal Exposition of Paris 1889. The piece composed by Rameau after his impression of the “savages’” music (Les Sauvages) is revolutionary for the history of music, with its coarse contours and enthralling rhythms, and is paralleled – in its refined, deliberate roughness – only by his own Les Cyclopes, also recorded here. Rameau would re-use the music of Les Sauvages in his ballet Les Indes Galantes, ten years later.

Les Cyclopes is excerpted, together with Les tendres plaintes, from Rameau’s Suite in D found in his Livre de pièces de clavecin (1724). The monstrosity of the cyclops is evoked by the capricious, odd style of the piece; their sheer force and power are suggested by the vigorous musical movements punctuating the piece. Further, the cyclops are the Greek gods’ blacksmiths, and their constant hammering on their anvils is reproduced through brilliant sequences of repeated notes. A totally different atmosphere is that conjured by La Follette, full of elegance, sparkling vitality, and a richly ornamented texture of quintessentially French embellishments. Also in La Joyeuse the waterfall of crystal-clear descending scales seems to evoke the silvery tingling of a young person’s laughter, and the lively motion of the entire piece suggests the robust vitality of a joyful character. By way of contrast, Les Tendres Plaintes is almost pre-Romantic in its melancholic gestures, full of pathos and rhetoric, but also of genuinely human affections.

Other pieces by Rameau recorded here are excerpted (like Les sauvages) from the famous G-minor Suite, which consists nearly completely of character pieces. Les tricotets is an almost folkloric depiction of the deft motion of knitting, “translated” into sounds via the similar motions of the keyboardist’s hands. L’enharmonique is an enigmatic piece, built on the (near) equivalence between the two notes which are played on the same key (for instance, C sharp and D flat), which allows for harmonic ambiguity and daring turns of phrase. Some more exoticism (to the East rather than to the West, in this case) is found in L’egiptienne (this was Rameau’s spelling), whereby the Oriental component is seen through the filter of Otherness – represented by gypsy culture.

These themes are also powerfully found in Debussy’s music. Hommage à Rameau, purposefully recalling the tradition of the Tombeaux (homages to deceased masters) practiced in France (see also Ravel’s Tombeau de Couperin) is excerpted from Images, where, indeed, the “Impressionist” and the “Neoclassicist” strains are both represented. Within Images I, Hommage à Rameau follows immediately the “Monetian” Reflets dans l’eau; it is written as a free Sarabande. This piece, though an integral part of the cycle, can also be played individually, as was done in 1905 by Maurice Dumesnil. Another cycle of Images oubliées (or Inédites) was written in 1894, and it included a Sarabande: Souvenir du Louvre. This other Sarabande found later its way within Pour le Piano, one of the earliest piano masterpieces by Debussy. It is a suite explicitly inspired by Baroque music, albeit seen through the lens of modernity. Its three movement explore novel forms of piano technique, derived from Liszt’s models but also creatively innovative.

The Suite Bergamasque is another example of Debussy’s dialogue with the past, and a work on which the composer returned again and again from 1890 until 1905. At its heart, Clair de lune is the most famous movement, with its enchanted atmospheres and liquid sonorities; however, the other movements show several elements derived from Baroque music. The opening Prelude has something of the improvisatory style of harpsichord Toccatas; the Menuet following it has the courtly irony of the refined pastime; in the concluding Passepied (just as in the Prelude opening Pour le piano) the evocation of an historical exoticism (the Baroque era) is combined with that of geographical exoticism (the gamelan, i.e. Java’s orchestra). As Rameau had done with Iroquois music in Les Sauvages, here Debussy too is inspired by music from far away, which becomes familiar through estrangement and exotic through kinship.

01. Pour le Piano: I. Prélude

02. Pour le Piano: II. Sarabande

03. Pour le Piano: III. Toccata

04. from Suite en Sol, RCT 6: Les Sauvages

05. from Suite en Sol, RCT 6: Les Tricotets

06. Hommage à Rameau: /

07. from Suite en Sol, RCT 6: L’Enharmonique

08. from Suite en Sol, RCT 6: L’Egyptienne

09. Suite Bergamasque: I. Prélude

10. Suite Bergamasque: II. Menuet

11. Suite Bergamasque: III. Clair de Lune

12. Suite Bergamasque: IV. Passepied

13. from Suite en Ré, RCT 3: Les Tendres Plaintes

14. from Suite en Ré, RCT 3: La Joyeuse

15. from Suite en Ré, RCT 3: La Follette

16. from Suite en Ré, RCT 3: Les Cyclopes

Is there anything like a “national style” in music? This is a thorny question, and one invested with very sensitive political aspects which can undermine from the outset every attempt at an honest answer. In literature, of course, the use of a certain language creates a kinship among its speakers. Even though there is a world of difference between – say – Flaubert and Sartre, or Hugo and Rabelais, still there is a common ground, a forma mentis, a shared background which ensures a certain degree of continuity. A language creates attitudes, forms of thought; they are not the only or the essential component of affinity, but certainly they are not to be dismissed lightly. It is certainly possible to say that Dostoevsky and Hugo are closer to each other than Hugo and Rabelais; still, the net of influences is so deep and structural that, possibly, there would have been no Hugo without Rabelais. Furthermore, there are nature and culture beside language, and even though culture evolves in turn (and so do, within limits, both landscapes and natural aspects), still people who were born in the same country will have a shared background with their fellow citizens.

To evoke a “national style” in music, as previously said, is riskier. The ghosts of nationalism show themselves easily, stereotypes abound, and the definition of what could count as “national” is frequently polluted by assessment of quality and value. Yet, if it is true that (possibly) there would have been no Hugo without a Rabelais, as different as these two authors may be, it is also true that there would have (possibly) been no Debussy and no Ravel without Rameau and Couperin. From a certain viewpoint, there is as huge and wide a difference between Debussy and Rameau as between Rabelais and Hugo. Debussy is normally labelled as the representative of musical “Impressionism”. The qualities associated with Impressionism in the visual arts are, among others, the abolition of contour and the use of juxtapositions of colours to create a “vibration”, an effect of indefiniteness similar to that of light in real life. In music, this translates in the acceptability of the juxtaposition and even superimposition of different, discordant harmonies. On the piano, a time-honoured dogma is subverted: “changing the pedal with each new harmony”, in order to keep each and every harmony “pure”, is no more a prescription. Once-incompatible harmonies can now resound together, creating a “vibration” of sound which parallels Monet’s enchanting effects of water and light. Rameau wrote for the harpsichord, where the entire concept of piano pedalling is entirely alien.

On the piano, the right pedal lifts the whole array of the dampers, which normally lie on the strings preventing them from vibrating. When the dampers are lifted, all strings become capable of resonating; those which have been hit by the hammers will keep vibrating until the phenomenon ceases naturally (or until the pedal is released and the dampers fall down again), but also the others will be called to vibration by the phenomenon of sympathetic resonance. On the harpsichord, there is no need for the pedal, because the plucked strings’ natural resonance is much lighter and much shorter than that of the piano. The pedal would not make any significant difference. Thus, even though there doubtlessly are sympathetic resonances on the harpsichord, this instrument is generally seen as the prototype of cleanness, transparency, neat lines and clear contours.

From this viewpoint, therefore, there is little if any contact between Rameau and Debussy. But, going beyond the surface of things, there is a whole world of common traits, or, at least, of possible influences. First and foremost, Debussy himself acknowledged the importance of Rameau for French music and for his own style. Debussy cannot be defined as a representative of musical nationalism in the same fashion as, for instance, Sibelius for Finland or Mussorgsky for Russia. However, Debussy’s reaction against musical Romanticism was also (doubtlessly) a reaction against Germany, where musical Romanticism had flourished most. And, even though Debussy was a great admirer of Bach, he was also keen on promoting French Baroque music, and claiming for it the status of “classic” which seemed to be due only to the German Baroque.

Second, the label of “Impressionist” does certainly apply to some works by Debussy (such as, for instance, La Cathédrale engloutie or Poissons d’or), but by no means to all. Other of his works are distinctly symbolist (typically Pelléas et Mélisande), but there is also a Neoclassical stream in his output – one which predates musical Neoclassicism proper. One could arguably say that there are at least as many piano works by Debussy where lines are clearly cut and colours sharply opposed as works with nuances of sound and timbre and the suppression of harmonic “contours”.

Furthermore (and without, of course, any pretense to exhaust the subject!) there is the fascination of both composers for music inspired by visual impressions or extramusical promptings. Rameau, following a tradition which was not exclusive for France, but certainly deeply rooted in his country, used to label many of the pieces constituting his Suites with descriptive titles. These could, at times, refer directly and patently to some aspects of musical descriptivism (such as birdsong, for instance); at times, the nexus is harder to grasp, especially without some kind of musicological background.

In 1725, two “savages” (as the American natives were, alas, disparagingly labelled at the time) were brought from Louisiana to Paris, and they performed a warrior dance in various venues, including the Theatre of the Italian Comedy. Their performance impressed the audience enormously, although with varying degrees of enthusiasm. Rameau was fascinated by the exoticism of what he saw and heard: and this, in turn, is something that unites Rameau with Debussy, whose musical style was deeply influenced by the “exotic” music he heard at the Universal Exposition of Paris 1889. The piece composed by Rameau after his impression of the “savages’” music (Les Sauvages) is revolutionary for the history of music, with its coarse contours and enthralling rhythms, and is paralleled – in its refined, deliberate roughness – only by his own Les Cyclopes, also recorded here. Rameau would re-use the music of Les Sauvages in his ballet Les Indes Galantes, ten years later.

Les Cyclopes is excerpted, together with Les tendres plaintes, from Rameau’s Suite in D found in his Livre de pièces de clavecin (1724). The monstrosity of the cyclops is evoked by the capricious, odd style of the piece; their sheer force and power are suggested by the vigorous musical movements punctuating the piece. Further, the cyclops are the Greek gods’ blacksmiths, and their constant hammering on their anvils is reproduced through brilliant sequences of repeated notes. A totally different atmosphere is that conjured by La Follette, full of elegance, sparkling vitality, and a richly ornamented texture of quintessentially French embellishments. Also in La Joyeuse the waterfall of crystal-clear descending scales seems to evoke the silvery tingling of a young person’s laughter, and the lively motion of the entire piece suggests the robust vitality of a joyful character. By way of contrast, Les Tendres Plaintes is almost pre-Romantic in its melancholic gestures, full of pathos and rhetoric, but also of genuinely human affections.

Other pieces by Rameau recorded here are excerpted (like Les sauvages) from the famous G-minor Suite, which consists nearly completely of character pieces. Les tricotets is an almost folkloric depiction of the deft motion of knitting, “translated” into sounds via the similar motions of the keyboardist’s hands. L’enharmonique is an enigmatic piece, built on the (near) equivalence between the two notes which are played on the same key (for instance, C sharp and D flat), which allows for harmonic ambiguity and daring turns of phrase. Some more exoticism (to the East rather than to the West, in this case) is found in L’egiptienne (this was Rameau’s spelling), whereby the Oriental component is seen through the filter of Otherness – represented by gypsy culture.

These themes are also powerfully found in Debussy’s music. Hommage à Rameau, purposefully recalling the tradition of the Tombeaux (homages to deceased masters) practiced in France (see also Ravel’s Tombeau de Couperin) is excerpted from Images, where, indeed, the “Impressionist” and the “Neoclassicist” strains are both represented. Within Images I, Hommage à Rameau follows immediately the “Monetian” Reflets dans l’eau; it is written as a free Sarabande. This piece, though an integral part of the cycle, can also be played individually, as was done in 1905 by Maurice Dumesnil. Another cycle of Images oubliées (or Inédites) was written in 1894, and it included a Sarabande: Souvenir du Louvre. This other Sarabande found later its way within Pour le Piano, one of the earliest piano masterpieces by Debussy. It is a suite explicitly inspired by Baroque music, albeit seen through the lens of modernity. Its three movement explore novel forms of piano technique, derived from Liszt’s models but also creatively innovative.

The Suite Bergamasque is another example of Debussy’s dialogue with the past, and a work on which the composer returned again and again from 1890 until 1905. At its heart, Clair de lune is the most famous movement, with its enchanted atmospheres and liquid sonorities; however, the other movements show several elements derived from Baroque music. The opening Prelude has something of the improvisatory style of harpsichord Toccatas; the Menuet following it has the courtly irony of the refined pastime; in the concluding Passepied (just as in the Prelude opening Pour le piano) the evocation of an historical exoticism (the Baroque era) is combined with that of geographical exoticism (the gamelan, i.e. Java’s orchestra). As Rameau had done with Iroquois music in Les Sauvages, here Debussy too is inspired by music from far away, which becomes familiar through estrangement and exotic through kinship.

Year 2024 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads