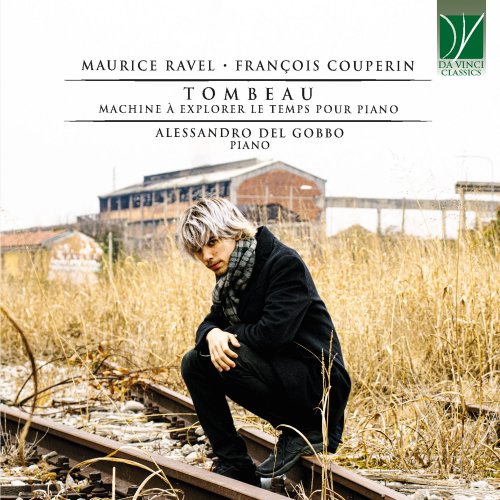

Alessandro Del Gobbo - Maurice Ravel, François Couperin: Tombeau (Machine à explorer le temps pour piano) (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Alessandro Del Gobbo

- Title: Maurice Ravel, François Couperin: Tombeau (Machine à explorer le temps pour piano)

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:52:20

- Total Size: 176 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

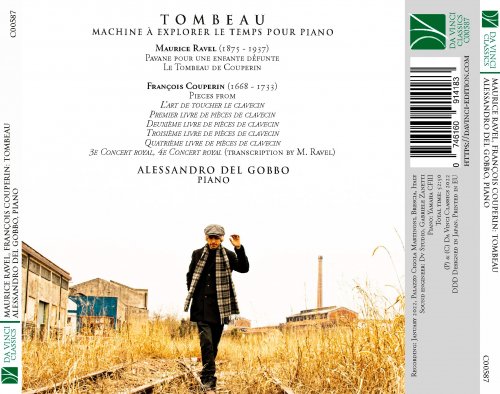

01. Pavane pour une enfante défunte in G Major

02. L'art de toucher le clavecin: Huitième prélude

03. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 1 in E Minor, Prélude

04. Second Livre de Pièces de clavecin-Huitième Ordre: No. 10 in B Minor, La Morinète

05. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 2 in E Minor, Fugue

06. Troisième livre de pièces de clavecin-Quatorzième Ordre: No. 4, Les Fauvètes plaintives

07. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 3 in E Minor, Forlane

08. Concert Royaux No. 4: I. Forlane (Transcription by Maurice Ravel)

09. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 4 in C Major, Rigaudon

10. Quatrième Livre de Pièces de Clavecin-Vingtième Ordre: No. 11, Les Tambourins

11. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 5 in G Major, Menuet

12. Premier livre de pièces de clavecin-Premier ordre: No. 7, Menuet (et double)

13. Concert Royaux No. 3: Muzette

14. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 6 in E Minor, Toccata

15. Troisième livre de pièces de clavecin-Dix-huitième Ordre: No. 6, Le Tic-Toc choc, ou les Maillotins

The transition from a concept of music as an ephemeral phenomenon to a historicist view of music was an epoch-making change. Prior to the nineteenth century, music was, almost by definition, contemporary music (with the notable exception of Church music, where ancient plainchants and early polyphony had been in continuing use). Then, an interest for early/earlier music began to arise, at first in England, and then in Germany, where it intertwined with the rediscovery of Johann Sebastian Bach. This happened at a time when, in both France and Italy, in the common feeling music was primarily opera: the nineteenth century was the century of Rossini, Verdi, Puccini, or Meyerbeer, Bizet, Massenet and other great operatic composers. Thus, a chasm began to appear. On the one hand, there was the Great German Tradition, characterized by an august line of composers, mostly… with surnames beginning with a B (Bach, Beethoven, Brahms…); they wrote “absolute music”, as Hanslick would call it, i.e. instrumental music, or sacred music to German lyrics. On the other hand, the hybrid genre of opera, with its catchy tunes, its staging and costumes, its “stories”, and the tendency to favour novelty and innovation.

Musicology, with the name of Musikwissenschaft, was beginning to blossom in the German-speaking countries, where phenomena such the masterful Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe bore witness to a new scholarly concept of music and to critical criteria applied to music. This in turn brought about a “canon” of composers of instrumental music, which were mainly from the German-speaking area: Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms etc.

These musical and cultural projects were not without nationalistic overtones, especially at a time when Germany, as a political identity, was fashioning itself. That time was also a moment when political rivalries were rather fierce among the European countries which today belong in a single political entity, the European Union. Thus, musicians from “peripheral” areas (the Mediterranean, but also Northern countries such as Scandinavia, or Eastern countries such as Czechia, Slovakia, Poland, Russia etc.) claimed for their own musical traditions a status comparable to that of the Great German Tradition.

Within this framework, Italians fought for Scarlatti’s equality, or near-equality, to Bach, and the French claimed an equal footing for Couperin. Many of the pioneers of the “rebirth” of Italian and French instrumental music in the late nineteenth century were also among the rediscoverers of local Baroque composers, whose works they edited and transcribed.

This had a particular value at those difficult times in which the tendency of a given country is to gather around their flag, such as at times of war. Maurice Ravel had been interested in the music of François Couperin for a very long time, and to early music in general since almost the very outset of his compositional activity.

His Pavane pour une enfante defunte was published already in 1900, dedicated to the composer’s patroness, the Princess of Polignac. This exquisite piece alludes to the Pavane, an ancient, stately dance, normally juxtaposed to the lively, at times frantic Gaillarde. The composed pace of the Pavane and its association with processional movements fostered the suggestive mental association with a funeral cortege, but also with nobility, and with the grace one attributes to a princess. Another obvious allusion was to Spain, where royal princesses were called “infanta”, and their portraits were famously painted by Diego Velázquez. As would be the case with the Tombeau de Couperin, Ravel realized an appreciated orchestration of this piece. In spite of this, in later times the composer became dissatisfied with this work and its relatively simple structure.

Nevertheless, his fascination with bygone epochs would not fade. He was not alone: Debussy’s Suite bergamasque also displays similar artistic influences. For Ravel, though, these were a fundamental part of his poetics. The liquid, elusive, “Impressionistic” aspect of his music was powerfully balanced with a clear-cut, black-and-white, “Classicist” component, which seems to anticipate Neoclassicism.

The composer began working on his Tombeau de Couperin in the years immediately preceding World War I. Tombeaux were a form of post-mortem homage paid by living composers to their dead colleagues, and typically characterized the Baroque era. Since the very title, then, Ravel looked back to an earlier tradition, and fashioned himself as the direct continuator of a tradition which he imagined as uninterrupted. Just as Louis Couperin and J. J. Froberger had written Tombeaux for Blancrocher, d’Angelebert one for Chambonnières and so on, Ravel saw himself as a “near contemporary” of Couperin, or perhaps as his direct heir. This does not imply, though, an anachronistic or antiquarian reconstruction of an artificial past: Ravel is no Viollet-Leduc, even though the latter’s works are very artistical in their turn.

Preparing for his homage to Couperin, Ravel tried his hand in transcribing a Forlane by the Baroque composer. Forlanes were originally sung dances from the Venetian tradition of the “gondolieri”, which later were adopted in the large repertoire of dances of the French court, and Couperin had written a famous example of this instrumental dance in the fourth of his Concerts Royaux. This transcription is very fittingly included in the programme of this fascinating Da Vinci Classics album, whereby the individual movement of Ravel’s Tombeau are juxtaposed to their possible, or direct, models in Couperin’s oeuvre.

Ravel’s Tombeau, however, went beyond the official dedicatee of his homage. In the composer’s own words, “The homage is directed less to Couperin himself than to French music of the eighteenth century”. As said before, this was felt with particular intensity at a time when culture seemed one of the things worth fighting for, along with identity and patriotism.

Indeed, the composition of Ravel’s Tombeau was arrested by the deflagration of the War. In spite of his mature age and of his frail constitution, Ravel’s patriotism led him to repeatedly request to be enrolled in the Army. He was denied admission for several times, and finally served as a medical aid, and as a truck driver. He served gallantly, experimenting the horrors of the Verdun battle, and courageously assisting his fellow soldiers. Whilst he narrowly escaped death, others were less fortunate; among them, several of his friends. When he could resume writing, having been dismissed for health reasons, and after the death of his mother, Ravel returned to the Tombeau, and dedicated each of its movements to one of these “casualties” in the horrible carnage of World War I. The Prélude is dedicated to Jacques Charlot, a musician who had realized some transcriptions of Ravel’s orchestral works for solo piano; the Fugue to Jean Cruppi, the Forlane to Gabriel Deluc, from Saint-Jean-de-Luz, the Rigaudon to Pierre and Pascal Gaudin. These two brothers, coming from the same city as Ravel, were killed on the same day. The Menuet bears a dedication to Jean Dreyfus, the son-in-law of Ravel’s marraine de guerre – these were women who volunteered to write letters to soldiers during wartime. Ravel completed his Tombeau at her place. Finally, the concluding Toccata is consecrated to the memory of a musicologist, Joseph de Marliave. He was the husband of a great pianist, Marguerite Long, who would premiere Ravel’s Tombeau to great success after the end of the war. This premiere took place in Paris, on April 11th, 1919, at the Salle Gaveau, having been postponed due to the bombings of the French capital.

Ravel later orchestrated his suite, expunging the two movements which reveal their pianistic inspiration more closely.

One of the acoustic impressions Ravel brought home after his service in the Army was that of the unreal silence following a battle. After the thundering noise of cannons, the cries, the explosions, what remained was a burnt nature – with leafless trees – and the absence of movement, life, sounds. As a friend of Ravel once recounted, “As a truck driver at Verdun, Ravel witnessed the most indescribable chaos and the most deafening noise of war. The silence following the battle seemed supernatural, the peace returning to the countryside, a limpid sky and then suddenly, at daybreak, the song of a warbler [fauvette]. He was so captivated by this unexpected song that he vowed to write a piece, ‘La fauvette indifférente’. But war and illness prevented him from realizing this project”. This piece Ravel never wrote is yet another homage to Couperin, who composed several pieces inspired by birdsong, and in particular one which is recorded in this album (Les Fauvètes plaintives). Another friend of Ravel, Manuel Rosenthal, argued that the never-composed piece was intended to become part of Ravel’s Tombeau de Couperin. And even though no indifferent warbler is found in this suite, undeniably, there is a trace of birdsong “quietly encapsulated in the Menuet of Le tombeau, piping a quiet descant over the last echoes of the desolate Musette”, as Howat wrote in 2009.

Among the other pieces recorded here, La Morinète is worth noting being still another homage – this time Couperin’s – to a musician, Jean-Baptiste Morin, who composed Baroque cantatas which paved the way for a new concept of the French Cantata, and the concluding piece, Le tic-toc-choc, one of Couperin’s best-known pieces. Its depiction of a clockwork rhythm conflicting with song is perhaps yet another instance of how a certain French irony can look with depth and lightness to the mystery of life, of time, of death, and of a song which seems to encompass them all.

01. Pavane pour une enfante défunte in G Major

02. L'art de toucher le clavecin: Huitième prélude

03. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 1 in E Minor, Prélude

04. Second Livre de Pièces de clavecin-Huitième Ordre: No. 10 in B Minor, La Morinète

05. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 2 in E Minor, Fugue

06. Troisième livre de pièces de clavecin-Quatorzième Ordre: No. 4, Les Fauvètes plaintives

07. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 3 in E Minor, Forlane

08. Concert Royaux No. 4: I. Forlane (Transcription by Maurice Ravel)

09. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 4 in C Major, Rigaudon

10. Quatrième Livre de Pièces de Clavecin-Vingtième Ordre: No. 11, Les Tambourins

11. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 5 in G Major, Menuet

12. Premier livre de pièces de clavecin-Premier ordre: No. 7, Menuet (et double)

13. Concert Royaux No. 3: Muzette

14. Le Tombeau de Couperin: No. 6 in E Minor, Toccata

15. Troisième livre de pièces de clavecin-Dix-huitième Ordre: No. 6, Le Tic-Toc choc, ou les Maillotins

The transition from a concept of music as an ephemeral phenomenon to a historicist view of music was an epoch-making change. Prior to the nineteenth century, music was, almost by definition, contemporary music (with the notable exception of Church music, where ancient plainchants and early polyphony had been in continuing use). Then, an interest for early/earlier music began to arise, at first in England, and then in Germany, where it intertwined with the rediscovery of Johann Sebastian Bach. This happened at a time when, in both France and Italy, in the common feeling music was primarily opera: the nineteenth century was the century of Rossini, Verdi, Puccini, or Meyerbeer, Bizet, Massenet and other great operatic composers. Thus, a chasm began to appear. On the one hand, there was the Great German Tradition, characterized by an august line of composers, mostly… with surnames beginning with a B (Bach, Beethoven, Brahms…); they wrote “absolute music”, as Hanslick would call it, i.e. instrumental music, or sacred music to German lyrics. On the other hand, the hybrid genre of opera, with its catchy tunes, its staging and costumes, its “stories”, and the tendency to favour novelty and innovation.

Musicology, with the name of Musikwissenschaft, was beginning to blossom in the German-speaking countries, where phenomena such the masterful Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe bore witness to a new scholarly concept of music and to critical criteria applied to music. This in turn brought about a “canon” of composers of instrumental music, which were mainly from the German-speaking area: Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms etc.

These musical and cultural projects were not without nationalistic overtones, especially at a time when Germany, as a political identity, was fashioning itself. That time was also a moment when political rivalries were rather fierce among the European countries which today belong in a single political entity, the European Union. Thus, musicians from “peripheral” areas (the Mediterranean, but also Northern countries such as Scandinavia, or Eastern countries such as Czechia, Slovakia, Poland, Russia etc.) claimed for their own musical traditions a status comparable to that of the Great German Tradition.

Within this framework, Italians fought for Scarlatti’s equality, or near-equality, to Bach, and the French claimed an equal footing for Couperin. Many of the pioneers of the “rebirth” of Italian and French instrumental music in the late nineteenth century were also among the rediscoverers of local Baroque composers, whose works they edited and transcribed.

This had a particular value at those difficult times in which the tendency of a given country is to gather around their flag, such as at times of war. Maurice Ravel had been interested in the music of François Couperin for a very long time, and to early music in general since almost the very outset of his compositional activity.

His Pavane pour une enfante defunte was published already in 1900, dedicated to the composer’s patroness, the Princess of Polignac. This exquisite piece alludes to the Pavane, an ancient, stately dance, normally juxtaposed to the lively, at times frantic Gaillarde. The composed pace of the Pavane and its association with processional movements fostered the suggestive mental association with a funeral cortege, but also with nobility, and with the grace one attributes to a princess. Another obvious allusion was to Spain, where royal princesses were called “infanta”, and their portraits were famously painted by Diego Velázquez. As would be the case with the Tombeau de Couperin, Ravel realized an appreciated orchestration of this piece. In spite of this, in later times the composer became dissatisfied with this work and its relatively simple structure.

Nevertheless, his fascination with bygone epochs would not fade. He was not alone: Debussy’s Suite bergamasque also displays similar artistic influences. For Ravel, though, these were a fundamental part of his poetics. The liquid, elusive, “Impressionistic” aspect of his music was powerfully balanced with a clear-cut, black-and-white, “Classicist” component, which seems to anticipate Neoclassicism.

The composer began working on his Tombeau de Couperin in the years immediately preceding World War I. Tombeaux were a form of post-mortem homage paid by living composers to their dead colleagues, and typically characterized the Baroque era. Since the very title, then, Ravel looked back to an earlier tradition, and fashioned himself as the direct continuator of a tradition which he imagined as uninterrupted. Just as Louis Couperin and J. J. Froberger had written Tombeaux for Blancrocher, d’Angelebert one for Chambonnières and so on, Ravel saw himself as a “near contemporary” of Couperin, or perhaps as his direct heir. This does not imply, though, an anachronistic or antiquarian reconstruction of an artificial past: Ravel is no Viollet-Leduc, even though the latter’s works are very artistical in their turn.

Preparing for his homage to Couperin, Ravel tried his hand in transcribing a Forlane by the Baroque composer. Forlanes were originally sung dances from the Venetian tradition of the “gondolieri”, which later were adopted in the large repertoire of dances of the French court, and Couperin had written a famous example of this instrumental dance in the fourth of his Concerts Royaux. This transcription is very fittingly included in the programme of this fascinating Da Vinci Classics album, whereby the individual movement of Ravel’s Tombeau are juxtaposed to their possible, or direct, models in Couperin’s oeuvre.

Ravel’s Tombeau, however, went beyond the official dedicatee of his homage. In the composer’s own words, “The homage is directed less to Couperin himself than to French music of the eighteenth century”. As said before, this was felt with particular intensity at a time when culture seemed one of the things worth fighting for, along with identity and patriotism.

Indeed, the composition of Ravel’s Tombeau was arrested by the deflagration of the War. In spite of his mature age and of his frail constitution, Ravel’s patriotism led him to repeatedly request to be enrolled in the Army. He was denied admission for several times, and finally served as a medical aid, and as a truck driver. He served gallantly, experimenting the horrors of the Verdun battle, and courageously assisting his fellow soldiers. Whilst he narrowly escaped death, others were less fortunate; among them, several of his friends. When he could resume writing, having been dismissed for health reasons, and after the death of his mother, Ravel returned to the Tombeau, and dedicated each of its movements to one of these “casualties” in the horrible carnage of World War I. The Prélude is dedicated to Jacques Charlot, a musician who had realized some transcriptions of Ravel’s orchestral works for solo piano; the Fugue to Jean Cruppi, the Forlane to Gabriel Deluc, from Saint-Jean-de-Luz, the Rigaudon to Pierre and Pascal Gaudin. These two brothers, coming from the same city as Ravel, were killed on the same day. The Menuet bears a dedication to Jean Dreyfus, the son-in-law of Ravel’s marraine de guerre – these were women who volunteered to write letters to soldiers during wartime. Ravel completed his Tombeau at her place. Finally, the concluding Toccata is consecrated to the memory of a musicologist, Joseph de Marliave. He was the husband of a great pianist, Marguerite Long, who would premiere Ravel’s Tombeau to great success after the end of the war. This premiere took place in Paris, on April 11th, 1919, at the Salle Gaveau, having been postponed due to the bombings of the French capital.

Ravel later orchestrated his suite, expunging the two movements which reveal their pianistic inspiration more closely.

One of the acoustic impressions Ravel brought home after his service in the Army was that of the unreal silence following a battle. After the thundering noise of cannons, the cries, the explosions, what remained was a burnt nature – with leafless trees – and the absence of movement, life, sounds. As a friend of Ravel once recounted, “As a truck driver at Verdun, Ravel witnessed the most indescribable chaos and the most deafening noise of war. The silence following the battle seemed supernatural, the peace returning to the countryside, a limpid sky and then suddenly, at daybreak, the song of a warbler [fauvette]. He was so captivated by this unexpected song that he vowed to write a piece, ‘La fauvette indifférente’. But war and illness prevented him from realizing this project”. This piece Ravel never wrote is yet another homage to Couperin, who composed several pieces inspired by birdsong, and in particular one which is recorded in this album (Les Fauvètes plaintives). Another friend of Ravel, Manuel Rosenthal, argued that the never-composed piece was intended to become part of Ravel’s Tombeau de Couperin. And even though no indifferent warbler is found in this suite, undeniably, there is a trace of birdsong “quietly encapsulated in the Menuet of Le tombeau, piping a quiet descant over the last echoes of the desolate Musette”, as Howat wrote in 2009.

Among the other pieces recorded here, La Morinète is worth noting being still another homage – this time Couperin’s – to a musician, Jean-Baptiste Morin, who composed Baroque cantatas which paved the way for a new concept of the French Cantata, and the concluding piece, Le tic-toc-choc, one of Couperin’s best-known pieces. Its depiction of a clockwork rhythm conflicting with song is perhaps yet another instance of how a certain French irony can look with depth and lightness to the mystery of life, of time, of death, and of a song which seems to encompass them all.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads