There is something in the sound quality and timbre of the viola which makes this instrument particularly suited for nostalgia, for the evocation of autumnal moods, for longing, regret, but also the peaceful contemplation of life, as if from afar. These qualities emerge in many of the masterpieces written for this instrument, from Brahms to Kancheli. Less outspoken and showy than the violin, but also less patently expressive than the cello, the viola unites the qualities of both of its siblings but seems to display a preference of the more intimate nuances.

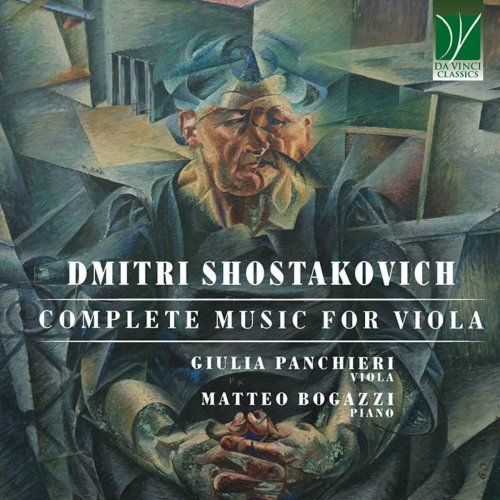

This Da Vinci Classics CD explores how the sound of the viola lends its voice to the extraordinarily varied palette of nuances, emotions, feelings, affections, and moods called for by the music of Dmitrij Šostakovič.

Unanimously counted among the greatest composers of the twentieth century, and within the Gotha of the entire history of classical music, Šostakovič is a figure which does not fit well within any preordered narrative. And this happens also because the circumstances in which he operated, lived, and worked, are hardly comparable to those experienced by any major composer of the West, at any time of the history of Western music.

The entire parable of Šostakovič’s compositional activity and most of his life unfolded during the decades of Soviet totalitarianism. The Communist regime in the URSS took different forms and shades in the more than seventy years elapsing from 1917 and 1989. There were periods of pure terror, when nobody could feel safe; indeed, precisely those who had been at the forefront of political engagement within the very same Communist party were the targets of the most violent campaigns, ending in torture, exile, death. Other periods were comparatively more tolerant and tolerable, even though the taste of liberty constantly eluded the thirst of Soviet citizens. And this was felt with particular anguish and pain especially by those gifted with greater sensitivity, intelligence, culture, or intuition.

Šostakovič was certainly one of them. His position was unique in the panorama of contemporaneous music. On the one hand, he was admired, revered, respected, even idolized by his contemporaries in the URSS. He was a model, a mentor, an inspiration for all great composers of the generations following his own. The likes of Schnittke, Denisov, Gubaidulina, Kancheli, and all other major creators who were his juniors considered Šostakovič as an undisputed maestro. The same applied to the genius performers of the former Soviet Union, from Oistrakh to Rostropović, to name but two. And even at the official level, Šostakovič managed to gain appreciation and a rather solid position.

What is unique about him is that he was able to acquire this comparatively uncontroversial official situation with the Soviet authorities without compromising his conscience and his honesty. Even in music, which is probably the most impalpable and elusive of all arts, the regime had its own set of “values”, its aesthetics, its principles; and it was by no means hesitant in imposing them on all composers of the Soviet area. The ideals of the “Soviet realism”, which transpire clearly and evidently in the monster buildings erected by the regime, or in the colossal statues celebrating Soviet heroes, workers, farmers, or soldiers, were applied also to music. Music had to be positive and positivist, optimistic, unproblematic; it had to be joyful, denying the unspeakable sorrows of the Soviet citizens – from the Ukrainians led to an atrocious famine to those deported to Siberia for religious or political convictions. It had to be “Russian”, i.e. to express a nationalism which actually collided with the ideals of internationalism otherwise propounded by Communist ideologues.

Some composers were able to comply with these prescriptions. Their works are by no means disagreeable to listen to – indeed, they are supremely pleasing, since these were precisely the directives imposed on them. Or by them: in fact, there was an organization, the Union of Composers, which ruled over all music written and performed in the Soviet Union. All composers had to be members of the Union; and, without the Union’s approval, no new score could be performed, printed, let alone recorded. On the other hand, it must be said that the Union provided magnificently for its members – particularly for the most important ones: countless facilitations in terms of primary goods, services, but also of creative retreats in idyllic zones of Russia were offered to composers in order to sustain their creative efforts.

Some musicians, with extreme and admirable courage, refused to comply with this system. They had to write the music they felt compelled to write by their artistic conscience, and they accepted to be marginalized, hungered, and ignored, when not outright persecuted. These were the likes of those cited above: genius musicians whose works were frequently unknown by either their fellow citizens or the inhabitants of the “free” Western countries.

Šostakovič did not take such an extreme stance; he was mainly in good or passable relationships with the Soviet government, even though the period of the craziest Stalinist persecutions took its toll also from him (as from Prokofev). At the same time, his music is never a mere submission to the imposed aesthetics, and he did what he could, also on the personal plane, to help his less fortunate or his younger colleagues.

The tension between obedience to the Party and interior freedom is beautifully exemplified in the works recorded here, and entrusted to the intimate voice of the viola, which seems to speak the composer’s soul.

On the one hand, we have the transcriptions after pieces from the film music for The Gadfly. Many Soviet composers wrote numerous film scores, different from their Western colleagues, who normally either specialized in film music or in “serious” compositions. It is difficult to imagine an Indiana Jones movie with music by Stockhausen or a Star Wars episode with music by Pierre Boulez. Contrariwise, some masterpieces of Soviet film music have entered the classical repertoire and are regularly performed in concert halls (one example may suffice: Prokofev’s Alexander Nevskij). For dissident composers such as Schnittke, film music was a providential haven: film scores did not have to be approved by the Union of Composers, and therefore their authors were free to express their deepest and most intimate feelings without fear of repression. (And, at the same time, such commissions offered them some help toward survival). Šostakovič composed many beautiful scores, at times for splendid movies (such as Kozintsev’s King Lear); in the case of The Gadfly, the subject is quintessential Soviet art (the story of an Italian revolutionary in the nineteenth century, who is persecuted by a bigoted alliance of Church and monarchical State, but whose greatest love are revolutionary ideals), and there was the need for such typical topoi of Soviet music as folk intermezzos and picturesque dances. Šostakovič managed to create unforgettable tunes and musical gestures for this all, and the result acquired immediate and lasting fame. Pieces from this soundtrack were also adopted by Western media, and became very popular also to the West of the Berlin Wall.

On the other hand, however, Šostakovič pursued infinity, and was open to the mystery of life which the Soviet regime was keen on stifling or denying. And his very last work speaks clearly of his quest for an answer which could transcend the banality of a merely horizontal thought. His Viola Sonata is the last page which came from his fecund pen, and is a compendium of his whole artistic life, with a significant and meaningful opening to transcendence. He wrote this piece when he was already seriously ill with the cancer which would lead him to his death. He completed the score mere days before entering the hospital where he would spend his last weeks, in an isolation ward. He would never be able to hear this piece performed: it would receive its private premiere on the day when Šostakovič’s sixty-ninth birthday was posthumously celebrated, and later be performed, to universal acclaim, in an extraordinary memorial concert.

The first movement seems to stage the tensions involving musical language – the crux of all twentieth-century composers, to be sure, but also a cross particularly hard to bear for Soviet composers, whose research of and quest for a language of their own was constantly scrutinized by the Regime. An impossible dialogue between twelve-tone composition and diatonicism demonstrates the complexity of the challenges faced by modern composers, in a cry for artistic freedom which the ailing composer was now entirely free to let loose. The second movement features a grotesque, sarcastic, or ironical vein – one which was typical for Šostakovič, and which frequently expressed his truest feelings. Regimes often cannot understand irony, and it is comparatively easy to mock them without criticizing them openly. And Šostakovič’s works had often done this.

But it is with the third movement that Šostakovič allows his soul to speak most clearly. Written in memory of Beethoven, or “of a Great Composer”, it weaves reminiscences from Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata with countless quotes from Šostakovič’s own works (most notably, all of his Symphonies). Toward the end, it opens up on an extraordinary C-major section, labeled as “radiance” by Šostakovič himself. It is a rather clear expression of hope in the afterlife; or, at least, the desire to be remembered for the things of beauty he had written throughout his life. But these alone could not justify that light, that purity, that desire for luminosity which the simple, extraordinary C major conveys.

The programme is completed by an album leaf, fortuitously found as late as 2017. It is a token of friendship written by Šostakovič, probably “impromptu” as the very title states; scholars agree in affirming that it must have been written in a single brushstroke – which is unsurprising given the composer’s fervid and fertile imagination.

Together, these three very different scores, all entrusted to the elegiac sound of the viola, narrate the creativity, fantasy, and genius of Šostakovič, and the unique story of his life.