In 1943, Thomas Stearns Eliot issued, as a unified collection, a series of poems he had written and individually published in the years between 1935 and 1942. He collectively called them Four Quartets, with an explicit reference to music, and, in particular, to the late string quartets written by Ludwig van Beethoven. These poems are indeed built on musical forms and principles, with a first “movement” in the Sonata form, a second “movement” similar to a Romance with two different harmonizations of the same theme, a third “movement” which acts as the static/contemplative moment (as in a slow movement), a fourth “movement” recalling the recitative/aria combination, and a fifth movement which seems to explore the contrapuntal possibilities of words, employing techniques which allude to those of polyphony.

This cycle is one of the absolute masterpieces of twentieth-century poetry; it is authored by a poet who is usually seen as the epitome of modernism. If this is technically correct, one should also observe the correlation between Eliot’s poetry and the values behind and beyond it, considering the role of Eliot’s religious conversion in fostering his reappropriation of the past.

The question about form and content, language and meaning, is in fact crucial not only for Eliot and for his poetry, but also for each and any artist, in whatever artistic field, throughout the twentieth and twenty-first century.

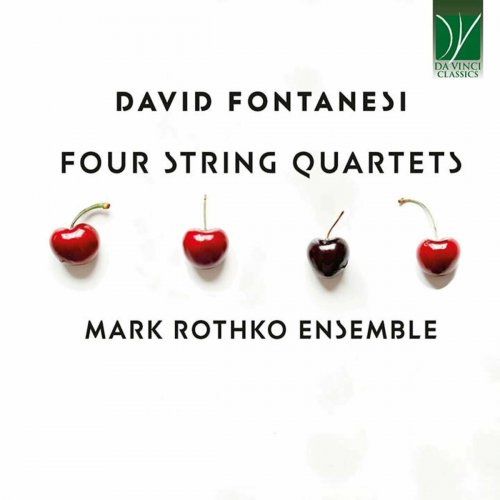

And here we get to the protagonist of this Da Vinci Classics album, David Fontanesi, whose personality and music seem to embody the tensions of contemporaneity as concerns form, content, language and style in musical terms. His own “four Quartets”, recorded here, are a demonstration of how some aporias of today’s musical world can be overcome without ignoring them; of how it is possible to find a way out with respect to the aphasia which characterizes so substantial a portion of today’s compositions – provided that one actually seeks for that way out.

Eliot’s poetry, in parallel with his religious conversion, passed from a really hermetic style, made of purposefully absurd (and therefore thought-provoking, to be sure) juxtapositions, to a language which is no less complex (and certainly neither naïve nor simplistic) but is also warmer, more communicative, more accessible. This happens because he incorporates in his poetry an increasing quantity of references to the literary past, in the form of direct quotations (in a variety of languages) and allusions. This not only demonstrates his prodigious culture and omnivorous reading, but also works as a bridge between Eliot and his readers. It constitutes a common ground, rooted in the Classical culture of the West; Eliot’s references and allusions, once decoded, enrich his poetry with a quantity of symbolic layers which can be savoured and appreciated by his readers. His references to the past and to literary tradition thus become the shared language which connects the poet with his audience, and which opens up his poetry to a fresher understanding and more immediate enjoyment. Certainly, however, this never implies that his poetry becomes trivial or déjà vu. Quite the contrary: it is precisely by giving new meanings to known elements that the revolution of Eliot’s language is accomplished.

This seems, in my eyes, very similar to what Fontanesi does with his own Four Quartets. Fontanesi does not refer explicitly to Eliot’s poetry (the analogy is my own), but there are many points in common. The fact that both Fontanesi and Eliot wrote four Quartets is also without a direct relationship: Fontanesi frequently conceives his works by groups of four, and this happened – before the Quartets – to his organ sonatas, to his concertos (for brass, for strings, for percussions), to his other concertos for solo instruments and orchestra etc. “All revolves around the number four, and it has been this way for some years; its squareness contains an idea of solidity”, the composer states.

However, the points in common between composer and poet are numerous, and go well beyond the number four or the form of the string quartet. Both artists questioned the dogmatic approach of the avantgardes to art, struggled with it, and managed to find a language of their own, where the problems and issues of modernity are by no means ignored or avoided, but they are also not allowed to determine the entire spectrum of expressive research. Both artists lived in times where Thomas W. Adorno’s famous, cutting aphorism could be applied: in Adorno’s words, “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. And this corrodes even the knowledge of why it has become impossible to write poetry today”. The impossibility (according to Adorno) of articulating a poetical discourse – of believing in a dimension of beauty which is inherent in poetry and music, and indispensable for them both – causes the aphasia of modernity. But if catastrophes such as Auschwitz do undermine a certain kind of naivety, of sugary poetry, the fact remains that poetry and music are needs for the human being. And that it is precisely by cultivating beauty that some kind of resistance against the evil and horror of the Holocaust and of other wounds of contemporaneity can be built.

The response of the musical avantgardes to the tragedies of the twentieth century has been to seek and deliberately adopt a language which represents a total rupture with what preceded it. A language which frequently seems to degenerate into inarticulate cries; a language which fails to do precisely what a language is made for – i.e. to communicate.

“As a composer”, Fontanesi maintains, “I find myself in an isolated position with respect to contemporary music. I never believed in avant-garde music, and I criticized it substantially also in writing. I think that it experiences a conflict with tradition which led the so-called Neue Musik to cut off its roots and its connections with the nucleus of Western music”. Fontanesi’s critique is to the point, when he observes that, on the one hand, the avantgardes had the pretense to be universally acknowledged; but, on the other, they maintained a very elitist attitude face the audience. The language of the avantgardes is purposefully made to disconcert the listener, but, at the same time, those practising it complain when nobody seems to “understand” them.

However, Fontanesi is also clear that the classical alternative to the avantgardes is not more satisfying in his eyes. Since the 1980s, the harshness of the avantgardes has been responded by the “Neoromantics”, whose approach to language and to the past seems to ignore what happened in culture and society throughout the twentieth century and beyond it. “There is, in many of them, some shabbiness: compositional research is virtually missing, as is harmonic exploration, counterpoint, study of timbre”. Thus, Fontanesi frankly identifies as a “conservative” composer, but also refuses to be identified with any one of these two currents. “The composer’s task is not primarily to ‘communicate emotions’: his or her own private emotions are uninteresting. Rather, they have to provoke and elicit emotions through music”. This is what Fontanesi seeks to do with his music, and which marks the main difference between it and that of many contemporary musicians.

“The audience was accused by many musicologists of being unable to understand contemporary music. But it is neither necessary nor sufficient to understand the composer’s technique in order to appreciate a musical work. Aesthetic fruition precedes technical understanding; the latter can magnify and increase the pleasure of listening, but cannot determine it”.

Novelty for novelty’s sake is a dead end: “It is the beautiful that composers and artists should seek. And this beauty is beyond the scope not only of the avantgardes, but also of the Neoromantics: one should be after a beauty beyond technical polish, after something which could be universally acknowledged as ‘beautiful’. In my music”, explains Fontanesi, “I constantly keep looking to the past: to a past when composers clearly knew what made formal and musical beauty”.

Thus, Fontanesi’s music studies, analyzes, reinterprets and recreates the main pillars of Western music, in its three main forms: “The theme with variations, whereby composers can demonstrate their capability of invention; the fugue (implying contrapuntal technique in general), highlighting one’s technical skill; and the Sonata form where both aspects merge, elaborating invention and technique in a complex form”.

And this is what happens in Fontanesi’s Four Quartets. The first two are structured as Sonatas, with either a traditional Sonata allegro or a Theme with variations as the first movement, a Scherzo, a slow movement and a finale which is, respectively, a Rondo (first Quartet) or a Fugue (second Quartet). The third Quartet is seamlessly built as a single movement; it is a kind of chaconne constructed on a descending tetrachord (C-B flat-A flat-G, which later assumes other forms: C-B flat-A-G, C-B-A-G#, or C-B-A-G). It is a tightly structured piece which gives the impression of timelessness. The last quartet looks back to the form of the Church Sonata as it was practised in the seventeenth century, and with the typical alternation between a slow introductory movement (Poco adagio), a contrapuntal Allegro (a fugue), an Andante, here in the form of a Barcarola, and a Finale. It is a Vivace on a perpetuum mobile presented by the cello, in the form of a Rondo.

The form and the musical discourse are extremely clear and transparent when one hears them even for the first time. The articulation of the musical material is made of phrases, periods, refrains, couplets, subjects and countersubjects, canons, and progressions. In a word, of what music was made of for centuries.

“I believe”, states Fontanesi, “that the compositional act always springs forth from an intuition of the spirit. Through the mediation of intelligence and technique it assumes such a form that it moves and touches the strings of feelings in those who hear it. Without this action which pierces the human spirit, soul and body, I don’t believe that true art can exist”. Certainly, such clear statements are deliberately countercultural. Yet, one needs only to listen to these superb pieces to perceive, immediately and self-evidently, that the future of music (if it wants to be heard) passes from this approach.

“Music heard so deeply / That it is not heard at all, but you are the music / While the music lasts”. So did Eliot put it in his Four Quartets; and such is the experience of those listening to Fontanesi’s own Four Quartets.