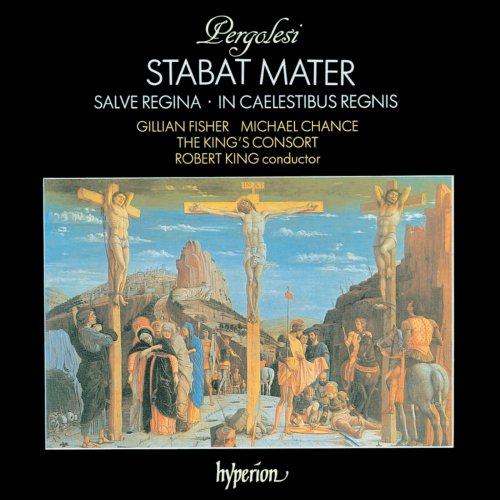

The King's Consort, Robert King - Pergolesi: Stabat Mater; Salve Regina in A Minor (1988)

BAND/ARTIST: The King's Consort, Robert King

- Title: Pergolesi: Stabat Mater; Salve Regina in A Minor

- Year Of Release: 1988

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 00:54:03

- Total Size: 206 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Stabat Mater, P. 77: I. Duet. Stabat Mater dolorosa

02. Stabat Mater, P. 77: II. Soprano. Cuius animam gementem

03. Stabat Mater, P. 77: III. Duet. O quam tristis et afflicta

04. Stabat Mater, P. 77: IV. Alto. Quae moerebat et dolebat

05. Stabat Mater, P. 77: V. Duet. Quis est homo qui non fleret

06. Stabat Mater, P. 77: VI. Soprano. Vidit suum dulcem natum

07. Stabat Mater, P. 77: VII. Alto. Eia mater, fons amoris

08. Stabat Mater, P. 77: VIII. Duet. Fac, ut ardeat cor meum

09. Stabat Mater, P. 77: IX. Duet. Sancta mater

10. Stabat Mater, P. 77: X. Alto. Fac, ut portem Christi mortem

11. Stabat Mater, P. 77: XI. Duet. Inflammatus et accensus

12. Stabat Mater, P. 77: XII. Duet. Quando corpus morietur – Amen

13. Salve Regina in A Minor: I. Salve Regina

14. Salve Regina in A Minor: II. Ad te clamamus

15. Salve Regina in A Minor: III. Eia ergo

16. Salve Regina in A Minor: IV. O clemens, o pia

17. In caelestibus regnis

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi achieved only modest success during his short lifetime, but the twenty years following his death in 1736 (at the age of only twenty-six) saw an extraordinary change, turning him into one of the most-published composers of the eighteenth century. This vogue for his music also brought about numerous legends and compositional misattributions, many of which have persisted to this day.

Pergolesi’s fame was brought about in no small way by his one-act opera La serva padrona. In his native Naples, and indeed all over Italy, much of the spread of this work came from the troupes of travelling players who took Pergolesi’s operatic comedies into their repertory. The composer’s popularity was also helped by comments of affection by Queen Maria Amalia of Naples and President De Brosses. La serva padrona was produced as far away as Hamburg and Dresden, and on its second run in Paris in 1752 was the cause of the celebrated Querelle des Bouffons, the pamphlet war between the supporters of traditional French opera and the progressive fans of Italian opera buffa. The opera was published widely, even in translations (La servante maîtresse, Paris, 1752) and adaptations (The Favourite Songs in the Burletta La serva padrona, London, 1759). But, as the century progressed, overtaking this opera for popularity was Pergolesi’s setting of the Stabat mater. First published in London in 1749, it became the most frequently printed single work in the eighteenth century. It also appeared in many adaptations, including one by J S Bach titled Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden (without a BWV number).

The Stabat mater, a setting of the sequence for the Feast of Seven Dolours of the Blessed Virgin Mary, was written during Pergolesi’s last few months which he spent at the Franciscan monastery at the well-known spa of Pozzuoli. Pergolesi’s biographer, Villarosa, states that this was the composer’s last work and that it was written for the aristocracy at the church of Santa Maria dei Sette Dolori in Naples as a replacement for Alessandro Scarlatti’s Stabat mater. However, Boyer, writing in his Notices sur la vie et les ouvrages de Pergolese of 1772, dates the Salve regina in C minor (which was also transposed for alto in F minor) as Pergolesi’s final composition. Whatever the exact dating, it seems clear that Pergolesi was not expecting to recover from his illness (probably tuberculosis), for he had given his possessions to his aunt. Other writers have drawn parallels from these sad circumstances with those of Mozart and his Requiem; certainly Pergolesi, like Mozart, was buried in the common pit.

Other pro-Italian French writers also helped to create the legend of the Stabat mater. Rousseau, writing in 1754, described the opening bars of the work to be ‘the most perfect and most touching to have come from the pen of any musician’, and De Brosses called it ‘the master work of Latin music’, remarking on its ‘profoundly learned harmony’. Indeed, Pergolesi’s extraordinary harmonic language does at times seem to be ahead of its age, with a remarkable grasp of chromaticism in one of the earliest applications to sacred music of the bitter-sweet tone of expressive sensibility. But the work also contains, despite its unrelentingly sombre text, some distinctly operatic music, such as the jaunty ‘Quae moerebat’ (with an off-beat string accompaniment straight from the orchestra pit), the bouncing syncopations of ‘Inflammatus et accensus’ and a strong fugal alla breve at the central ‘Fac, ut ardeat’. Word-painting abounds, with graphic use of chromaticism at moments such as ‘morientem desolatum’, and dramatic dissonance at ‘Fac, ut portem Christi mortem’. But for the most part Pergolesi maintains a mood of supplication, with melodies of great tenderness.

Just as Pergolesi’s life and music have been the subject of legend and wrong attribution, performances of the Stabat mater too have been subject to almost every type of performance, from lush romantic orchestrations to the erroneous suggestion that the work should be performed by a two-part choir. We do not know for certain for whom the work was intended, but research into the modest resources that would have been available for a performance (had it ever taken place during Pergolesi’s life) at the church of Santa Maria, together with the work’s feeling of restrained sacred opera, lends the piece perfectly to a similarly modest, but nonetheless still quietly operatic, style of performance.

Large amounts of music contained in the modern Opera omnia of Pergolesi (printed in Rome in 1939–1942) have since been proved to be by other composers. Indeed, of the 148 works in this edition, 69 are misattributions, 49 are questionable, and only 30 may be considered genuine! At the same time, a large number of works attributed to Pergolesi, some of which may be genuine, were omitted. Most of these genuine works are dramatic or sacred choral pieces, but also surviving are three antiphons for solo voice and strings.

Two of these are settings for soprano of the Salve regina—one in A minor, the other that in C minor, mentioned above. The A minor setting, with its supplicatory text, contains many of the hallmarks of the Stabat mater, including the same style of expressive sensibility, with the wistful sighing ‘Ad te suspiramus’ and a quite beautiful closing ‘O clemens’; but the work also contains contrasting music at the strong ‘Ad te clamamus’.

The third antiphon, In caelestibus regnis, is a unique surviving work for alto and strings. It is an example of the short type of piece that Pergolesi might have found time to write in between his operatic commissions when he was maestro di cappella to the Duke of Maddaloni. (The Duke, himself an amateur cellist and the dedicatee of Pergolesi’s Cello Sonata, might well have enjoyed playing the work’s leaping bass line.) A setting of the text of an antiphon for a common saint at First Vespers (with the Alleluia suggesting Eastertide as the most likely period in the Church calendar), In caelestibus regnis shows a different side to Pergolesi’s sacred music, and another contrasting compositional facet of this extraordinary composer.

01. Stabat Mater, P. 77: I. Duet. Stabat Mater dolorosa

02. Stabat Mater, P. 77: II. Soprano. Cuius animam gementem

03. Stabat Mater, P. 77: III. Duet. O quam tristis et afflicta

04. Stabat Mater, P. 77: IV. Alto. Quae moerebat et dolebat

05. Stabat Mater, P. 77: V. Duet. Quis est homo qui non fleret

06. Stabat Mater, P. 77: VI. Soprano. Vidit suum dulcem natum

07. Stabat Mater, P. 77: VII. Alto. Eia mater, fons amoris

08. Stabat Mater, P. 77: VIII. Duet. Fac, ut ardeat cor meum

09. Stabat Mater, P. 77: IX. Duet. Sancta mater

10. Stabat Mater, P. 77: X. Alto. Fac, ut portem Christi mortem

11. Stabat Mater, P. 77: XI. Duet. Inflammatus et accensus

12. Stabat Mater, P. 77: XII. Duet. Quando corpus morietur – Amen

13. Salve Regina in A Minor: I. Salve Regina

14. Salve Regina in A Minor: II. Ad te clamamus

15. Salve Regina in A Minor: III. Eia ergo

16. Salve Regina in A Minor: IV. O clemens, o pia

17. In caelestibus regnis

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi achieved only modest success during his short lifetime, but the twenty years following his death in 1736 (at the age of only twenty-six) saw an extraordinary change, turning him into one of the most-published composers of the eighteenth century. This vogue for his music also brought about numerous legends and compositional misattributions, many of which have persisted to this day.

Pergolesi’s fame was brought about in no small way by his one-act opera La serva padrona. In his native Naples, and indeed all over Italy, much of the spread of this work came from the troupes of travelling players who took Pergolesi’s operatic comedies into their repertory. The composer’s popularity was also helped by comments of affection by Queen Maria Amalia of Naples and President De Brosses. La serva padrona was produced as far away as Hamburg and Dresden, and on its second run in Paris in 1752 was the cause of the celebrated Querelle des Bouffons, the pamphlet war between the supporters of traditional French opera and the progressive fans of Italian opera buffa. The opera was published widely, even in translations (La servante maîtresse, Paris, 1752) and adaptations (The Favourite Songs in the Burletta La serva padrona, London, 1759). But, as the century progressed, overtaking this opera for popularity was Pergolesi’s setting of the Stabat mater. First published in London in 1749, it became the most frequently printed single work in the eighteenth century. It also appeared in many adaptations, including one by J S Bach titled Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden (without a BWV number).

The Stabat mater, a setting of the sequence for the Feast of Seven Dolours of the Blessed Virgin Mary, was written during Pergolesi’s last few months which he spent at the Franciscan monastery at the well-known spa of Pozzuoli. Pergolesi’s biographer, Villarosa, states that this was the composer’s last work and that it was written for the aristocracy at the church of Santa Maria dei Sette Dolori in Naples as a replacement for Alessandro Scarlatti’s Stabat mater. However, Boyer, writing in his Notices sur la vie et les ouvrages de Pergolese of 1772, dates the Salve regina in C minor (which was also transposed for alto in F minor) as Pergolesi’s final composition. Whatever the exact dating, it seems clear that Pergolesi was not expecting to recover from his illness (probably tuberculosis), for he had given his possessions to his aunt. Other writers have drawn parallels from these sad circumstances with those of Mozart and his Requiem; certainly Pergolesi, like Mozart, was buried in the common pit.

Other pro-Italian French writers also helped to create the legend of the Stabat mater. Rousseau, writing in 1754, described the opening bars of the work to be ‘the most perfect and most touching to have come from the pen of any musician’, and De Brosses called it ‘the master work of Latin music’, remarking on its ‘profoundly learned harmony’. Indeed, Pergolesi’s extraordinary harmonic language does at times seem to be ahead of its age, with a remarkable grasp of chromaticism in one of the earliest applications to sacred music of the bitter-sweet tone of expressive sensibility. But the work also contains, despite its unrelentingly sombre text, some distinctly operatic music, such as the jaunty ‘Quae moerebat’ (with an off-beat string accompaniment straight from the orchestra pit), the bouncing syncopations of ‘Inflammatus et accensus’ and a strong fugal alla breve at the central ‘Fac, ut ardeat’. Word-painting abounds, with graphic use of chromaticism at moments such as ‘morientem desolatum’, and dramatic dissonance at ‘Fac, ut portem Christi mortem’. But for the most part Pergolesi maintains a mood of supplication, with melodies of great tenderness.

Just as Pergolesi’s life and music have been the subject of legend and wrong attribution, performances of the Stabat mater too have been subject to almost every type of performance, from lush romantic orchestrations to the erroneous suggestion that the work should be performed by a two-part choir. We do not know for certain for whom the work was intended, but research into the modest resources that would have been available for a performance (had it ever taken place during Pergolesi’s life) at the church of Santa Maria, together with the work’s feeling of restrained sacred opera, lends the piece perfectly to a similarly modest, but nonetheless still quietly operatic, style of performance.

Large amounts of music contained in the modern Opera omnia of Pergolesi (printed in Rome in 1939–1942) have since been proved to be by other composers. Indeed, of the 148 works in this edition, 69 are misattributions, 49 are questionable, and only 30 may be considered genuine! At the same time, a large number of works attributed to Pergolesi, some of which may be genuine, were omitted. Most of these genuine works are dramatic or sacred choral pieces, but also surviving are three antiphons for solo voice and strings.

Two of these are settings for soprano of the Salve regina—one in A minor, the other that in C minor, mentioned above. The A minor setting, with its supplicatory text, contains many of the hallmarks of the Stabat mater, including the same style of expressive sensibility, with the wistful sighing ‘Ad te suspiramus’ and a quite beautiful closing ‘O clemens’; but the work also contains contrasting music at the strong ‘Ad te clamamus’.

The third antiphon, In caelestibus regnis, is a unique surviving work for alto and strings. It is an example of the short type of piece that Pergolesi might have found time to write in between his operatic commissions when he was maestro di cappella to the Duke of Maddaloni. (The Duke, himself an amateur cellist and the dedicatee of Pergolesi’s Cello Sonata, might well have enjoyed playing the work’s leaping bass line.) A setting of the text of an antiphon for a common saint at First Vespers (with the Alleluia suggesting Eastertide as the most likely period in the Church calendar), In caelestibus regnis shows a different side to Pergolesi’s sacred music, and another contrasting compositional facet of this extraordinary composer.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads