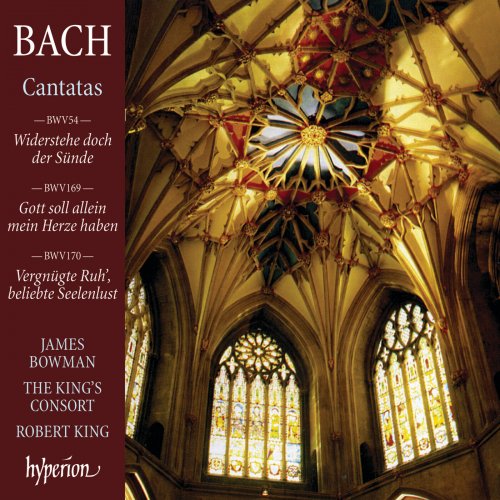

James Bowman, The King'S Consort, Robert King - Bach: Cantatas Nos. 54, 169 & 170 (1989)

BAND/ARTIST: James Bowman, The King'S Consort, Robert King

- Title: Bach: Cantatas Nos. 54, 169 & 170

- Year Of Release: 1989

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 00:59:00

- Total Size: 263 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170: No. 1, Aria. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust

02. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170: No. 2, Recit. Die Welt, das Sündenhaus

03. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170: No. 3, Aria. Wie jammern mich doch die verkehrten Herzen

04. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170: No. 4, Recit. Wer sollte sich demnach wohl hier zu leben wünschen

05. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170: No. 5, Aria. Mir ekelt mehr zu leben

06. Widerstehe doch der Sünde, BWV 54: I. Aria. Widerstehe doch der Sünde

07. Widerstehe doch der Sünde, BWV 54: II. Recit. Die Art verruchter Sünden

08. Widerstehe doch der Sünde, BWV 54: III. Aria. Wer Sünde tut, der ist vom Teufel

09. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: I. Sinfonia

10. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: II. Arioso e Recit. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben

11. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: III. Aria. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben

12. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: IV. Recit. Was ist die Liebe Gottes?

13. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: V. Aria. Stirb in mir

14. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: VI. Recit. Doch meint es auch dabei

15. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: VII. Chorale. Du süsse Liebe, schenk uns deine Gunst

Bach has always been thought of as an essentially practical composer, who wrote music because it was needed. Certainly this is true of the cantatas, produced usually for the principal Sunday service of the Lutheran church and scored for the available combinations of voices and instruments.

Although about two-fifths of Bach’s sacred cantatas are lost, some two hundred survive, of which the majority were composed in four cycles. The earliest handful of cantatas date from Bach’s Mühlhausen period (1707–8), but following his move to Weimar he seems to have concentrated on composing organ music. However, in 1714 he began his first cantata series, with the aim of producing a complete cycle over four years. Circumstances deteriorated in 1717 between Bach and his employer, Duke Wilhelm, and the Duke even briefly imprisoned his Kapellmeister before dismissing him in disgrace in December. At Cöthen, only secular cantatas were composed, and so it was not until his move to Leipzig in 1723 that Bach once again took up the composition of church cantatas.

A major requirement of the post as Kantor at the Thomaskirche was for the holder to produce a cantata every Sunday, as well as extra ones for principal feast days. The cantata was an integral part of the Lutheran liturgy, following the reading of the Gospel and preceding the Creed. For some of the congregation such a musical interlude must have come as a welcome break in the middle of a three-hour long service, but for Bach the weekly workload must have been enormous. For the first cycle of cantatas (1723–4) he had to rely on the occasional revision of an earlier sacred cantata, or even on a reworking (with a new libretto) of a secular cantata from Cöthen. Nonetheless, some forty new cantatas were written in that single year, and another fifty or so in the second cycle, dating from 1724–5. With this stock of cantatas continuous production appears to have ended, and the third cycle, spread between 1725 and 1727, finds new developments, including the re-use of earlier concerto material and the introduction of organ obbligato parts. The fourth cycle (1728–9) has all but disappeared, with only nine complete works surviving, and those cantatas written after 1729 contribute nothing essentially new.

Amongst the two hundred or so surviving sacred cantatas, only a dozen involve just one single soloist, most of them dating from the third cycle. Of this dozen, six have no requirement for a choir, even simply in a concluding chorale. Four are for alto soloist (BWV35, 54, 169 and 170), four are for soprano (BWV51, 52, 84 and 150), one for tenor (BWV55) and three for bass (56, 82 and 158). Of those with choir only one, and that a very early cantata indeed, BWV150 (1708), has a major role for the chorus. Three other solo cantatas originally thought to have been by Bach, and numbered in the Gesellschaft as BWV53, 160 and 189, are now considered to have been written by Telemann and Hoffman.

Vergnügte Ruh’, beliebte Seelenlust was first performed on 28 July 1726 on the sixth Sunday after Trinity with the text, as in many cantatas from that period, by Lehms. Of the twenty-four cantatas first performed in that year, two are for solo alto, suggesting that the St Thomaskirche must have been blessed with a particularly good voice at that time. In the first movement, Bach produced one of his musical gems, with the pastoral sound of oboe d’amore, strings and solo voice in a gently rocking 128 rhythm, and a glorious continuo line to match. The mood of the text changes for the recitative, and the aria that follows finds a much more angular vocal line, accompanied by a chromatic solo organ with both hands in the upper registers of the instrument; the bass line is played by unison violins and viola. After a short passage of accompanied recitative, the opening scoring returns, but with the addition of an obbligato organ part; given the text, this is a surprisingly cheerful movement with which to end the cantata.

Widerstehe doch der Sünde is an early work, most probably written in 1714 for the seventh Sunday after Trinity, and thus dating from the time when Bach was beginning his first cantata series. Newly acquainted with the Italian style, he began to take up recitative and the modern style of aria, for preference the da capo variety: this was a step which was to have a decisive effect on the subsequent sacred cantatas. Scored for two violins, two violas (another indication of the work’s early origins) and continuo, the cantata was written out in E flat major. However, knowing the pitch of the organ at Weimar to be at least a minor third sharp, the edition used in this recording (by David Munrow) transposes the work into F major. Even at this pitch, the voice part remains low, befitting a text full of references to sin and the devil. The opening movement contains some of Bach’s richest and most extraordinary harmonic writing, full of discords and suspensions. The final movement, separated from the first by a recitative of an even more foreboding text, is a winding and chromatic fugue representing, according to Whitaker, the twisted workings of the devil.

Gott soll allein mein Herze haben also dates from 1726, receiving its first performance on 20 October, the eighteenth Sunday after Trinity. Its extended opening Sinfonia and the siciliano ‘Stirb in mir’ were both re-workings of an earlier lost concerto, probably for oboe (reconstructed and recorded by Paul Goodwin and The King’s Consort on Helios CDH55269). Bach also re-used the same material in his E major harpsichord concerto (BWV1053), which dates from 1735–40. The Sinfonia, here set by Bach in D major, has a prominent solo role for an obbligato organ, as well as parts for strings and three oboes, and shows that Bach was unafraid to put a lengthy instrumental movement into a church cantata. With a harmonic requirement for an independent continuo instrument besides the solo organ, it seems likely that Bach would have used a harpsichord for this function. After the Sinfonia comes an extended passage of arioso and then an aria, scored for just voice, continuo and solo organ, the latter given a particularly sprightly right-hand line. With the second movement from the lost oboe concerto, we come to another of Bach’s gems, ‘Stirb in mir’: the solo organ, voice and strings weave their melodic lines through an enchanting siciliano before a short recitative and a simple chorale end the cantata.

01. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170: No. 1, Aria. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust

02. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170: No. 2, Recit. Die Welt, das Sündenhaus

03. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170: No. 3, Aria. Wie jammern mich doch die verkehrten Herzen

04. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170: No. 4, Recit. Wer sollte sich demnach wohl hier zu leben wünschen

05. Vergnügte Ruh', beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170: No. 5, Aria. Mir ekelt mehr zu leben

06. Widerstehe doch der Sünde, BWV 54: I. Aria. Widerstehe doch der Sünde

07. Widerstehe doch der Sünde, BWV 54: II. Recit. Die Art verruchter Sünden

08. Widerstehe doch der Sünde, BWV 54: III. Aria. Wer Sünde tut, der ist vom Teufel

09. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: I. Sinfonia

10. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: II. Arioso e Recit. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben

11. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: III. Aria. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben

12. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: IV. Recit. Was ist die Liebe Gottes?

13. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: V. Aria. Stirb in mir

14. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: VI. Recit. Doch meint es auch dabei

15. Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169: VII. Chorale. Du süsse Liebe, schenk uns deine Gunst

Bach has always been thought of as an essentially practical composer, who wrote music because it was needed. Certainly this is true of the cantatas, produced usually for the principal Sunday service of the Lutheran church and scored for the available combinations of voices and instruments.

Although about two-fifths of Bach’s sacred cantatas are lost, some two hundred survive, of which the majority were composed in four cycles. The earliest handful of cantatas date from Bach’s Mühlhausen period (1707–8), but following his move to Weimar he seems to have concentrated on composing organ music. However, in 1714 he began his first cantata series, with the aim of producing a complete cycle over four years. Circumstances deteriorated in 1717 between Bach and his employer, Duke Wilhelm, and the Duke even briefly imprisoned his Kapellmeister before dismissing him in disgrace in December. At Cöthen, only secular cantatas were composed, and so it was not until his move to Leipzig in 1723 that Bach once again took up the composition of church cantatas.

A major requirement of the post as Kantor at the Thomaskirche was for the holder to produce a cantata every Sunday, as well as extra ones for principal feast days. The cantata was an integral part of the Lutheran liturgy, following the reading of the Gospel and preceding the Creed. For some of the congregation such a musical interlude must have come as a welcome break in the middle of a three-hour long service, but for Bach the weekly workload must have been enormous. For the first cycle of cantatas (1723–4) he had to rely on the occasional revision of an earlier sacred cantata, or even on a reworking (with a new libretto) of a secular cantata from Cöthen. Nonetheless, some forty new cantatas were written in that single year, and another fifty or so in the second cycle, dating from 1724–5. With this stock of cantatas continuous production appears to have ended, and the third cycle, spread between 1725 and 1727, finds new developments, including the re-use of earlier concerto material and the introduction of organ obbligato parts. The fourth cycle (1728–9) has all but disappeared, with only nine complete works surviving, and those cantatas written after 1729 contribute nothing essentially new.

Amongst the two hundred or so surviving sacred cantatas, only a dozen involve just one single soloist, most of them dating from the third cycle. Of this dozen, six have no requirement for a choir, even simply in a concluding chorale. Four are for alto soloist (BWV35, 54, 169 and 170), four are for soprano (BWV51, 52, 84 and 150), one for tenor (BWV55) and three for bass (56, 82 and 158). Of those with choir only one, and that a very early cantata indeed, BWV150 (1708), has a major role for the chorus. Three other solo cantatas originally thought to have been by Bach, and numbered in the Gesellschaft as BWV53, 160 and 189, are now considered to have been written by Telemann and Hoffman.

Vergnügte Ruh’, beliebte Seelenlust was first performed on 28 July 1726 on the sixth Sunday after Trinity with the text, as in many cantatas from that period, by Lehms. Of the twenty-four cantatas first performed in that year, two are for solo alto, suggesting that the St Thomaskirche must have been blessed with a particularly good voice at that time. In the first movement, Bach produced one of his musical gems, with the pastoral sound of oboe d’amore, strings and solo voice in a gently rocking 128 rhythm, and a glorious continuo line to match. The mood of the text changes for the recitative, and the aria that follows finds a much more angular vocal line, accompanied by a chromatic solo organ with both hands in the upper registers of the instrument; the bass line is played by unison violins and viola. After a short passage of accompanied recitative, the opening scoring returns, but with the addition of an obbligato organ part; given the text, this is a surprisingly cheerful movement with which to end the cantata.

Widerstehe doch der Sünde is an early work, most probably written in 1714 for the seventh Sunday after Trinity, and thus dating from the time when Bach was beginning his first cantata series. Newly acquainted with the Italian style, he began to take up recitative and the modern style of aria, for preference the da capo variety: this was a step which was to have a decisive effect on the subsequent sacred cantatas. Scored for two violins, two violas (another indication of the work’s early origins) and continuo, the cantata was written out in E flat major. However, knowing the pitch of the organ at Weimar to be at least a minor third sharp, the edition used in this recording (by David Munrow) transposes the work into F major. Even at this pitch, the voice part remains low, befitting a text full of references to sin and the devil. The opening movement contains some of Bach’s richest and most extraordinary harmonic writing, full of discords and suspensions. The final movement, separated from the first by a recitative of an even more foreboding text, is a winding and chromatic fugue representing, according to Whitaker, the twisted workings of the devil.

Gott soll allein mein Herze haben also dates from 1726, receiving its first performance on 20 October, the eighteenth Sunday after Trinity. Its extended opening Sinfonia and the siciliano ‘Stirb in mir’ were both re-workings of an earlier lost concerto, probably for oboe (reconstructed and recorded by Paul Goodwin and The King’s Consort on Helios CDH55269). Bach also re-used the same material in his E major harpsichord concerto (BWV1053), which dates from 1735–40. The Sinfonia, here set by Bach in D major, has a prominent solo role for an obbligato organ, as well as parts for strings and three oboes, and shows that Bach was unafraid to put a lengthy instrumental movement into a church cantata. With a harmonic requirement for an independent continuo instrument besides the solo organ, it seems likely that Bach would have used a harpsichord for this function. After the Sinfonia comes an extended passage of arioso and then an aria, scored for just voice, continuo and solo organ, the latter given a particularly sprightly right-hand line. With the second movement from the lost oboe concerto, we come to another of Bach’s gems, ‘Stirb in mir’: the solo organ, voice and strings weave their melodic lines through an enchanting siciliano before a short recitative and a simple chorale end the cantata.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads