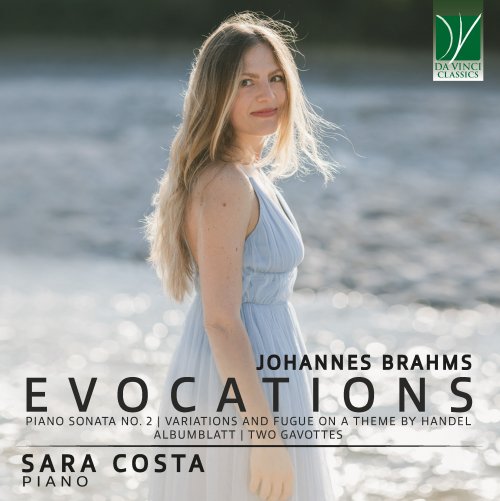

Sara Costa - Johannes Brahms: Evocations (Sonata No. 2, Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel, Albumblatt, Two Gavottes) (2024)

BAND/ARTIST: Sara Costa

- Title: Johannes Brahms: Evocations (Sonata No. 2, Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel, Albumblatt, Two Gavottes)

- Year Of Release: 2024

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:05:37

- Total Size: 183 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

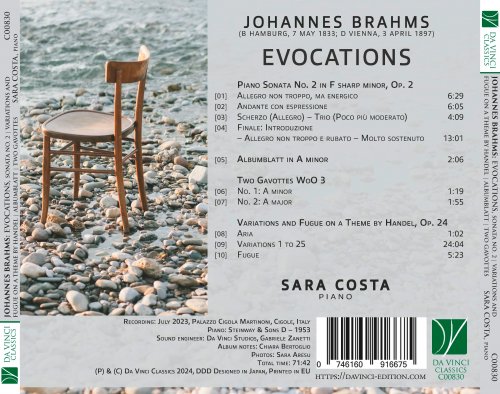

Tracklist

01. Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 2: I. Allegro non troppo, ma energico

02. Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 2: II. Andante con espressione

03. Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 2: III. Scherzo (Allegro) – Trio (Poco più moderato)

04. Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 2: IV. Finale: Introduzione – Allegro non troppo e rubato – Molto sostenuto

05. Albumblatt

06. Two Gavottes, WoO 3: No. 1 in A Minor

07. Two Gavottes, WoO 3: No. 2 in A Major

08. Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel in B-Flat Major, Op. 24: Aria

09. Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel in B-Flat Major, Op. 24: Variations 1 to 25

10. Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel in B-Flat Major, Op. 24: Fugue

After the medieval era in which music was written in the Church modes, in the seventeenth century just two of them imposed themselves over all others, and became the current “major” and “minor” mode. Together, they build up most of the musical material which is employed in the Western classical tradition. Still, the border between major and minor mode is not always clear-cut, and may incorporate some ambiguity. The difference between a major and minor chord lies in their thirds (a major third below and a minor above for the major chord, and vice-versa in the case of the minor chord); however, skilled composers may create situations in which the listener is left uncertain about the mode of a piece for a relatively long timespan. And Johannes Brahms was particularly eager to play this game of hide-and-seek with his listeners: his use of harmony and of the tonal language is extremely refined, and he manages to employ it in a manner which was unheard-of at his time. Furthermore, even when the mode is clear, by subtly shifting between major and minor, Brahms is able to refresh the aural impression of a theme or of a passage, which acquires a completely different shape when turned from major to minor and vice-versa.

In this Da Vinci Classics album, we observe some fine examples of this skill by the composer, and how he employed it for expressive purposes.

The most notable examples are probably found in his Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel op. 24. It was certainly not Brahms’ original idea to play on the major/minor relationship in a cycle of variations. Indeed, tradition required that, in a cycle of variations, at least one had to be written in the mode opposite to that of the theme: thus, at least one variation in the minor if the theme was in the major mode, and vice-versa. In the case of cycles with a high number of variations, such as, for instance, Beethoven’s 32 Variations in C minor, if one wished to maintain the correct proportions, the number of variations in the contrasting mode had to be increased.

Brahms deliberately assumed this tradition and the rules (both written and unwritten) it encompassed, when creating the magnificent set of Variations recorded here, and which can justly be counted among the finest examples of this genre in piano literature. The original theme on which they are built is by Handel, and the Baroque composer had written in turn some variations on it. Brahms, however, digs deep into the theme’s possibilities, in terms of musical expression and moods, and in terms of techniques, both compositional and pianistic. He effects the transition from the light, transparent, and somewhat uncomplicated language of Handel’s theme to the massive and complex language of the Romantic era by degrees; the first variations could easily be mistaken for original Baroque pieces, but already the fourth variation, with its powerful galloping octaves, makes it clear that Brahms was wearing no wigs when he wrote these Variations.

In conformity with some august models, such as Bach’s Goldberg Variations, several of these twenty-five variations are “character pieces”: we find, for instance, pieces reminiscent of hunting music and reproducing the sound and idiomatic passages of the horns, or, in another case, of the bagpipe; other pieces which seem to revert to the Baroque era, with lightly embellished pastoral suggestions; there are evocations of Hungarian or gipsy music; still others which explore the chromatic potential of the theme and its darker side (and these are, of course, in the minor mode). Many are technically very demanding; whilst perhaps the technical complexity will be further increased by Brahms in the two cycles of “Paganini” variations, it is likely that the perfect balance of musical fascination and technical difficulty found in the “Handel” variations remains unique.

The last variations build up a very powerful climax, in terms – here again – of both musicality and virtuosity, culminating in the triumphal last variation. Yet, this majestic ending is not an ending: it only launches the real conclusion, which is a long, superbly written and very complex fugue. As it happened in the Middle Ages and in the Baroque era, Brahms believed that the best way to pay homage to a theme and to demonstrate appreciation for it was to build a contrapuntal work on it. Here, Handel’s lightweight theme is totally transfigured and transformed into the germinating force of a solid architecture, beautifully constructed and magnificently built. The piano, which had mimicked a harpsichord in Handel’s theme, is here turned into a Romantic organ; several of Brahms’ ideas will be adopted by Ferruccio Busoni when transcribing Bach’s organ works for the piano.

This cycle was premiered by Clara Schumann, on Dec. 7th, 1861 in Hamburg. Brahms had dedicated it to a “beloved friend” and presented to her on the occasion of her forty-second birthday, in September of that same year. Clara wrote in her diary: “On Dec 7th I gave another soirée, at which I played Johannes’ Handel Variations. I was in agonies of nervousness, but I played them well all the same, and they were much applauded. Johannes, however, hurt me very much by his indifference. He declared that he could no longer bear to hear the variations, it was altogether too dreadful for him to listen to anything of his own and to have to sit by and do nothing. Although I can well understand this feeling, I cannot help finding it hard when one has devoted all one’s powers to a work, and the composer himself has not a kind word for it”.

Clara, who in 1861 had been widowed of Robert already for some years, had also been the dedicatee of Brahms’ Second Piano Sonata, op. 2, which was actually written before the “First” but published after it. The publication of these first fruits of Brahms’ artistic genius had been fostered and promoted precisely by Robert and Clara Schumann; Robert had sent a letter of recommendation to Breitkopf & Härtel, which would become Brahms’ reference publishers throughout his life.

Brahms’ interest in the form of variation is evident here; in fact, along with the cycles of variations proper, he would adopt variation-like forms in many other works. Here, in this Sonata, we find an exquisite set of variations on a German medieval song, Mir ist leide; and here too, the interplay between major and minor mode is both skillful and enchanting. Its opening movement is an enthralling Sonata allegro, built on an incisive theme played in octaves; it makes a strong contrast with the second theme, with a passionate theme moving in triplets with a rhythmic ambiguity typical for Brahms.

The second movement’s variations are few in number, but very intense in terms of expressivity; here, moreover, the framework within which the variations are inscribed is more flexible than in the Handel-Variations, and there is an insertion of fragments from the theme at the end of the second variation. The third is another notable example of how modal wavering can add depth and profundity to a theme and to its elaboration.

Following Beethoven’s model, the third movement is a Scherzo; here, however, Brahms demonstrates his brilliant imagination by deriving elements of this Scherzo from elements of the second movement. Another innovation imagined by the young Brahms is the fact that the Scherzo is not repeated identically and literally after the lyrical and pronouncedly embellished Trio, but rather is reinterpreted with innovative elements.

Other references which cross the Sonata’s movements are found in the Finale, which alludes from its very beginning to the first Theme of the opening Allegro. This movement shares with the first the same form, i.e. that of a Sonata Allegro, but reinterprets the traditional genre in innovative ways.

Whilst Brahms was not yet twenty when he composed this Sonata, his mastery of the form is tangible and his brilliant musical intelligence shines clearly.

The year after the composition of this Sonata, Brahms was touring Germany for concerts he was scheduled to perform in duo with violinist Ede Remnyi. During their journey, Brahms met the Music Director of the University of Göttingen, Arnold Wehner. As was usual at the time, Brahms was kindly asked to leave a sign of his passage on the liber amicorum of his host, on which other signatures of important musicians had been left or would be inscribed later.

Brahms, however, did not limit himself to a signature or to a few notes, as was common practice; rather, he wrote down an entire short piece, which is quite literally an Albumblatt, an “album leaf”. Ordinarily, being very selective with his own works, he would have destroyed such a miniature in his later years; here, however, he could not operate that ferocious self-censorship, since the piece had been left in a friend’s album. There, it laid completely forgotten for more than one and a half century, until, fortunately, Christopher Hogwood found it, unearthed it and had it published some years ago. However, even though in its original form it had laid silent for that long time, Brahms had not completely forgotten it: he employed it, transposed into A-flat minor, in his Horn Trio, written twelve years after the Göttingen tour.

In 1855, a couple of years after his composition of the Albumblatt, Brahms was busy working on another project which should have linked Romanticism with Baroque models. He had the idea in mind to write a Suite in the style of the ancient masters, and had sketched or thoroughly composed several movements of it. On September 12th, 1855, Clara Schumann wrote in her diary: “Johannes surprised me with a Prelude and Aria for his A-minor Suite, which is now complete”. Unfortunately, however, the Suite never came to light in this form. Only in 1917 and 1927 were individual movements of this Suite printed, but the two Gavottes (one in A minor and one, unfinished, in A major) had to wait until 1976, when another musicologist, Robert Pascall, found them. As with the Albumblatt, however, materials from this Suite resurfaced in other works by Brahms: in the mid-1860s, he employed fragments from the A-minor Gavotte in the String Sextet op. 36, in G major.

All of these works, therefore, bear witness to the flexibility and meaningfulness of tonal and modal patterns, and to how they can become expressive tools in the hand of a genius composer such as Brahms was already in his youthful years.

01. Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 2: I. Allegro non troppo, ma energico

02. Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 2: II. Andante con espressione

03. Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 2: III. Scherzo (Allegro) – Trio (Poco più moderato)

04. Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 2: IV. Finale: Introduzione – Allegro non troppo e rubato – Molto sostenuto

05. Albumblatt

06. Two Gavottes, WoO 3: No. 1 in A Minor

07. Two Gavottes, WoO 3: No. 2 in A Major

08. Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel in B-Flat Major, Op. 24: Aria

09. Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel in B-Flat Major, Op. 24: Variations 1 to 25

10. Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel in B-Flat Major, Op. 24: Fugue

After the medieval era in which music was written in the Church modes, in the seventeenth century just two of them imposed themselves over all others, and became the current “major” and “minor” mode. Together, they build up most of the musical material which is employed in the Western classical tradition. Still, the border between major and minor mode is not always clear-cut, and may incorporate some ambiguity. The difference between a major and minor chord lies in their thirds (a major third below and a minor above for the major chord, and vice-versa in the case of the minor chord); however, skilled composers may create situations in which the listener is left uncertain about the mode of a piece for a relatively long timespan. And Johannes Brahms was particularly eager to play this game of hide-and-seek with his listeners: his use of harmony and of the tonal language is extremely refined, and he manages to employ it in a manner which was unheard-of at his time. Furthermore, even when the mode is clear, by subtly shifting between major and minor, Brahms is able to refresh the aural impression of a theme or of a passage, which acquires a completely different shape when turned from major to minor and vice-versa.

In this Da Vinci Classics album, we observe some fine examples of this skill by the composer, and how he employed it for expressive purposes.

The most notable examples are probably found in his Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel op. 24. It was certainly not Brahms’ original idea to play on the major/minor relationship in a cycle of variations. Indeed, tradition required that, in a cycle of variations, at least one had to be written in the mode opposite to that of the theme: thus, at least one variation in the minor if the theme was in the major mode, and vice-versa. In the case of cycles with a high number of variations, such as, for instance, Beethoven’s 32 Variations in C minor, if one wished to maintain the correct proportions, the number of variations in the contrasting mode had to be increased.

Brahms deliberately assumed this tradition and the rules (both written and unwritten) it encompassed, when creating the magnificent set of Variations recorded here, and which can justly be counted among the finest examples of this genre in piano literature. The original theme on which they are built is by Handel, and the Baroque composer had written in turn some variations on it. Brahms, however, digs deep into the theme’s possibilities, in terms of musical expression and moods, and in terms of techniques, both compositional and pianistic. He effects the transition from the light, transparent, and somewhat uncomplicated language of Handel’s theme to the massive and complex language of the Romantic era by degrees; the first variations could easily be mistaken for original Baroque pieces, but already the fourth variation, with its powerful galloping octaves, makes it clear that Brahms was wearing no wigs when he wrote these Variations.

In conformity with some august models, such as Bach’s Goldberg Variations, several of these twenty-five variations are “character pieces”: we find, for instance, pieces reminiscent of hunting music and reproducing the sound and idiomatic passages of the horns, or, in another case, of the bagpipe; other pieces which seem to revert to the Baroque era, with lightly embellished pastoral suggestions; there are evocations of Hungarian or gipsy music; still others which explore the chromatic potential of the theme and its darker side (and these are, of course, in the minor mode). Many are technically very demanding; whilst perhaps the technical complexity will be further increased by Brahms in the two cycles of “Paganini” variations, it is likely that the perfect balance of musical fascination and technical difficulty found in the “Handel” variations remains unique.

The last variations build up a very powerful climax, in terms – here again – of both musicality and virtuosity, culminating in the triumphal last variation. Yet, this majestic ending is not an ending: it only launches the real conclusion, which is a long, superbly written and very complex fugue. As it happened in the Middle Ages and in the Baroque era, Brahms believed that the best way to pay homage to a theme and to demonstrate appreciation for it was to build a contrapuntal work on it. Here, Handel’s lightweight theme is totally transfigured and transformed into the germinating force of a solid architecture, beautifully constructed and magnificently built. The piano, which had mimicked a harpsichord in Handel’s theme, is here turned into a Romantic organ; several of Brahms’ ideas will be adopted by Ferruccio Busoni when transcribing Bach’s organ works for the piano.

This cycle was premiered by Clara Schumann, on Dec. 7th, 1861 in Hamburg. Brahms had dedicated it to a “beloved friend” and presented to her on the occasion of her forty-second birthday, in September of that same year. Clara wrote in her diary: “On Dec 7th I gave another soirée, at which I played Johannes’ Handel Variations. I was in agonies of nervousness, but I played them well all the same, and they were much applauded. Johannes, however, hurt me very much by his indifference. He declared that he could no longer bear to hear the variations, it was altogether too dreadful for him to listen to anything of his own and to have to sit by and do nothing. Although I can well understand this feeling, I cannot help finding it hard when one has devoted all one’s powers to a work, and the composer himself has not a kind word for it”.

Clara, who in 1861 had been widowed of Robert already for some years, had also been the dedicatee of Brahms’ Second Piano Sonata, op. 2, which was actually written before the “First” but published after it. The publication of these first fruits of Brahms’ artistic genius had been fostered and promoted precisely by Robert and Clara Schumann; Robert had sent a letter of recommendation to Breitkopf & Härtel, which would become Brahms’ reference publishers throughout his life.

Brahms’ interest in the form of variation is evident here; in fact, along with the cycles of variations proper, he would adopt variation-like forms in many other works. Here, in this Sonata, we find an exquisite set of variations on a German medieval song, Mir ist leide; and here too, the interplay between major and minor mode is both skillful and enchanting. Its opening movement is an enthralling Sonata allegro, built on an incisive theme played in octaves; it makes a strong contrast with the second theme, with a passionate theme moving in triplets with a rhythmic ambiguity typical for Brahms.

The second movement’s variations are few in number, but very intense in terms of expressivity; here, moreover, the framework within which the variations are inscribed is more flexible than in the Handel-Variations, and there is an insertion of fragments from the theme at the end of the second variation. The third is another notable example of how modal wavering can add depth and profundity to a theme and to its elaboration.

Following Beethoven’s model, the third movement is a Scherzo; here, however, Brahms demonstrates his brilliant imagination by deriving elements of this Scherzo from elements of the second movement. Another innovation imagined by the young Brahms is the fact that the Scherzo is not repeated identically and literally after the lyrical and pronouncedly embellished Trio, but rather is reinterpreted with innovative elements.

Other references which cross the Sonata’s movements are found in the Finale, which alludes from its very beginning to the first Theme of the opening Allegro. This movement shares with the first the same form, i.e. that of a Sonata Allegro, but reinterprets the traditional genre in innovative ways.

Whilst Brahms was not yet twenty when he composed this Sonata, his mastery of the form is tangible and his brilliant musical intelligence shines clearly.

The year after the composition of this Sonata, Brahms was touring Germany for concerts he was scheduled to perform in duo with violinist Ede Remnyi. During their journey, Brahms met the Music Director of the University of Göttingen, Arnold Wehner. As was usual at the time, Brahms was kindly asked to leave a sign of his passage on the liber amicorum of his host, on which other signatures of important musicians had been left or would be inscribed later.

Brahms, however, did not limit himself to a signature or to a few notes, as was common practice; rather, he wrote down an entire short piece, which is quite literally an Albumblatt, an “album leaf”. Ordinarily, being very selective with his own works, he would have destroyed such a miniature in his later years; here, however, he could not operate that ferocious self-censorship, since the piece had been left in a friend’s album. There, it laid completely forgotten for more than one and a half century, until, fortunately, Christopher Hogwood found it, unearthed it and had it published some years ago. However, even though in its original form it had laid silent for that long time, Brahms had not completely forgotten it: he employed it, transposed into A-flat minor, in his Horn Trio, written twelve years after the Göttingen tour.

In 1855, a couple of years after his composition of the Albumblatt, Brahms was busy working on another project which should have linked Romanticism with Baroque models. He had the idea in mind to write a Suite in the style of the ancient masters, and had sketched or thoroughly composed several movements of it. On September 12th, 1855, Clara Schumann wrote in her diary: “Johannes surprised me with a Prelude and Aria for his A-minor Suite, which is now complete”. Unfortunately, however, the Suite never came to light in this form. Only in 1917 and 1927 were individual movements of this Suite printed, but the two Gavottes (one in A minor and one, unfinished, in A major) had to wait until 1976, when another musicologist, Robert Pascall, found them. As with the Albumblatt, however, materials from this Suite resurfaced in other works by Brahms: in the mid-1860s, he employed fragments from the A-minor Gavotte in the String Sextet op. 36, in G major.

All of these works, therefore, bear witness to the flexibility and meaningfulness of tonal and modal patterns, and to how they can become expressive tools in the hand of a genius composer such as Brahms was already in his youthful years.

Year 2024 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads