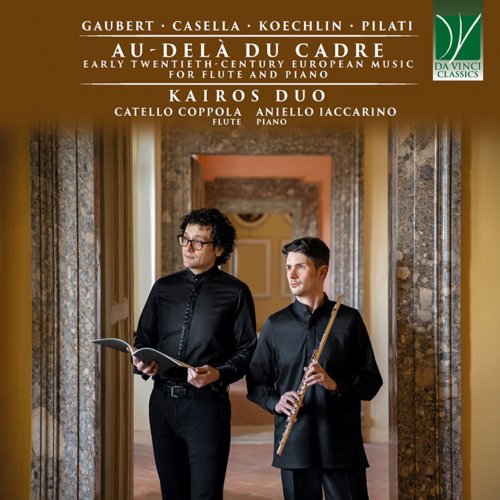

Catello Coppola, Aniello Iaccarino - Gaubert, Casella, Koechlin, Pilati: Au-Delà Du Cadre (Early Twentieth-Century European Music for Flute and Piano) (2024)

BAND/ARTIST: Catello Coppola, Aniello Iaccarino

- Title: Gaubert, Casella, Koechlin, Pilati: Au-Delà Du Cadre (Early Twentieth-Century European Music for Flute and Piano)

- Year Of Release: 2024

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:56:46

- Total Size: 191 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

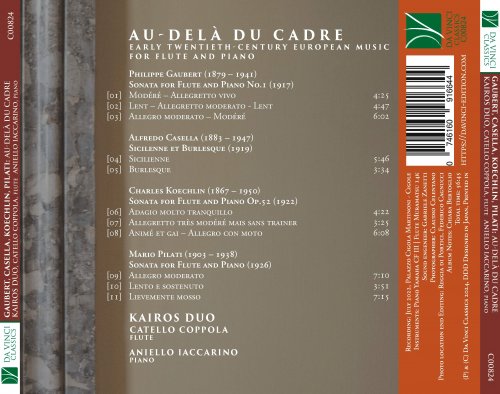

Tracklist

01. Sonata for Flute and Piano No.1 in A Major: I. Modéré – Allegretto vivo

02. Sonata for Flute and Piano No.1 in A Major: II. Lent – Allegretto moderato - Lent

03. Sonata for Flute and Piano No.1 in A Major: III. Allegro moderato – Modéré

04. Sicilenne et Burlesque in F-Sharp Major, Op. 23: I. Sicilienne

05. Sicilenne et Burlesque in F-Sharp Major, Op. 23: II. Burlesque

06. Sonata for Flute and Piano, Op. 52: I. Adagio molto tranquillo

07. Sonata for Flute and Piano, Op. 52: II. Allegretto très modéré mais sans trainer

08. Sonata for Flute and Piano, Op. 52: III. Animé et gai – Allegro con moto

09. Sonata for Flute and Piano: I. Allegro moderato

10. Sonata for Flute and Piano: II. Lento e sostenuto

11. Sonata for Flute and Piano: III. Lievemente mosso

Less than one decades divides the oldest from the most recent work recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album, which explores the repertoire for flute and piano written between 1917 and 1926. Two of the composers featured here were Frenchmen, two Italians – although one of them, Alfredo Casella, can be considered as almost French by virtue of his musical education.

In spite of the brief timespan covered by this recording, it also exemplifies the style and musical thought of two distinct generations. Charles Koechlin, the eldest composer represented here, was born in 1867, while Mario Pilati, the youngest, could have been his son, having been born in 1903. On the other hand, Pilati was the first among these four to pass away, at the young age of 35, in 1938; Koechlin would die twelve years later, at 73, in 1950.

The early life of Philippe Gaubert has something of the Romantic novel, even though the suffering it involved was very much real. Gaubert’s father was a shoemaker and an amateur clarinet player. Philippe was born in Cahors and, when the child was nine, the family moved to Paris where it was hoped the Philippe and his sibling could become professional musicians. Alas, their father died just three years later, leaving them rather destitute. In order to manage and support the household, Philippe’s mother worked as a housekeeper, and, fortunately for him, one of the homes where she worked was that of Jules Taffanel, a great flutist, and the father of an even greater flutist, Paul Taffanel. The Taffanels auditioned Philippe and were deeply impressed by his talent; Paul welcomed the boy in his class at the Conservatoire, where Philippe quickly demonstrated that their trust in him had been justified. Not only he graduated with honours at just fifteen in flute, immediately earning jobs in the most prestigious orchestras (he became first solo flutist at the Opéra orchestra in 1895), but he also studied with excellent results the violin and composition. In fact, his professor of composition was none other than Gabriel Fauré, and Gaubert showed his worth also in this field. In 1903 he got the premier prix in Fugue and Counterpoint, and two years later he nearly won the Prix de Rome. In the following years, Gaubert managed to maintain a successful career and activity in four distinct fields, in all of which he had roles of high responsibility. He was an appreciated performer, both as a flutist (although this branch of his activity was the first one to be renounced) and as a conductor; he taught extensively, transmitting the Taffanel tradition to the next generation of flutists (including among his students most notably Marcel Moyse) and conductors; he was in charge of important institutions (the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire and the Opéra); and, besides this all, he found time for composing numerous works which are today among his most important legacies (together with a method for flute playing which is still extremely valuable). Many of his works are written for the flute, even though the vastity of Gaubert’s professional experiences frees him from the narrow perspective which may affect other flutist-cum-composers.

Within his output, the three Flute Sonatas occupy pride of place; they were written in 1917, 1924, and 1933. They showcase Gaubert’s signature style, with his quest for lyricism, elegance, expressivity and a direct yet refined language.

The First Sonata is meaningfully dedicated “to the memory of [his] dear mentor”, Paul Taffanel. It opens on a calm mood (Modéré), characterized by a mellow atmosphere and sound, followed by a briskier and more brilliant section in C-sharp minor. A similar alternation of moods and of different beats characterizes the second movement, which juxtaposes a slow section (Lent) to a livelier part (Allegretto moderato in the compound time). The third and last movement plays on enchantment and wonder, and opens with some unforgettable measures where the narrative dimension is very pronounced. At the end of the movement, allusions to the very beginning of the Sonata encourage a cyclical reading of this score.

Gaubert’s interest in the explorations of sound and timbre which were particularly relevant for composers of his time is evident in this Sonata, where he requires specific sound qualities: “a very clear sonority”, or “a calm and penetrating sound”. Also as concerns the musical language he demonstrates his attention to contemporaneous explorations, for instance in his use of the whole-tone scale which had been popularized by Claude Debussy, especially in his Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune where the flute has a protagonist role.

Debussy had been a reference figure also for Alfredo Casella, who had been thunderstruck precisely by his listening of the Prélude. Similar to Gaubert, also Casella had studied with Fauré at the Conservatoire, where he had arrived at age 13, just as Gaubert, from his native city of Turin, Italy. However, Casella’s time at the Conservatoire ended rather abruptly due to his clash of wills with Maurice Ravel, whose perspective he could not espouse.

Casella considered himself therefore as mainly self-taught, but this did not prevent him from debuting with an ambitious work, a Symphony (1905) which he personally conducted in Monte Carlo three years later. During First World War, Casella returned to his homeland where he embarked in a successful career as a pianist (also in chamber music, having founded the extremely prestigious Trio Italiano together with Arturo Bonucci and Alberto Poltronieri), conductor, teacher of piano and composition, and organizer (he had created an important Society for the performance of contemporary music). His gaze was not turned only to the future, though; he was also deeply interested in the recovery of music of the past, particularly from Italy; he promoted the rediscovery of works by Antonio Vivaldi and by the Scarlattis (Alessandro and Domenico), and he championed the music of J. S. Bach. The instructive editions he realized of works by Bach, Beethoven and many others are still commonly employed, not only in Italy. He was also an appreciated author, who wrote poetry and prose, and who created the librettos for several of his own vocal works.

His Sicilienne and Burlesque exists in two versions (op. 23 and 23a respectively), the second of which is for piano trio and follows the earlier one, for flute and piano, by three years. The original work had been created for the Conservatoire of Paris at the time of Casella’s activity in the French Capital, and was conceived – as happened to many other short masterpieces by other great composers – as a pièce de concours for the final examinations of the Conservatoire. In this piece, Casella employs a very forward-looking harmonization, with ninth-chords, which punctuate the elegant, melancholic profile of the flute’s melody. The ironic vein of this composer surfaces in the following Burlesque, where allusions to both the folk tradition and the Italian musical heritage (Scarlatti) are observed.

Charles Koechlin had been, in turn, a student of Gabriel Fauré, but also of Jules Massenet. He would later teach at the same institution, contributing to the education of Darius Milhaud and Francis Poulenc. And whereas Casella was not in agreement with Ravel, Koechlin counted the composer among his friends, founding with him the Société musicale indépendante.

As a composer, Koechlin left a very significant output, in terms of both quantity and quality. It also demonstrates his high cultural profile and his knowledge of music from all ages. Koechlin’s erudition is also abundantly shown in his treatises and monographs, including a seminal one on Gabriel Fauré and textbooks for harmony and composition, some of which are still considered as reference points.

His Sonata op. 52 is his most important gift to the flute repertoire, but, meaningfully, he deliberately titled it “for piano and flute” rather than the other way around. In fact, his piano writing is very demanding, as is immediately visible even by looking at the score, with its constant use of the three staves. His refined writing is seen in his attention for the musical shades and nuances: as he imposes a dynamic straitjacket on the performers who are required not to go beyond certain volumes of sound, he also rewards their effort with a wealth of details. This discipline is broken, however, in the last movement, which is an explosion of musical ideas and a breathtaking run. The Sonata’s mood seems to bring in front of the interior eyes of the listener a variety of panoramas, some of which are distinctly Mediterranean. This Sonata is dedicated to Jeanne Herscher-Clément, a pianist who was the first performer of the work together with Adolphe Hennebains.

Mario Pilati was another child prodigy, whose musical accomplishment was evident at fifteen. He wrote the first version of his flute sonata when still in his teens: it was a two-movement Sonatina, which would later be elaborated in the form we now know. At twenty he graduated from the Conservatory of Naples, and the following year he was already a Conservatory professor in Cagliari. However, he thirsted for more musical experiences, and thus he left his job and moved to Milan, where he worked as a composer, pianist, conductor, musical critic, and also as a private teacher: among his pupils was Gianandrea Gavazzeni. His early career was an uninterrupted chain of successes, including victories at competitions awarding prizes or teaching posts. A particularly important moment was when the revised version of his youthful flute Sonatina, now in three movements, earned the prestigious Coolidge Prize, in memory of American patroness Elizabeth Sprague-Coolidge. This award, won at just 24, put him in the company of the likes of Stravinsky, Ravel, De Falla, Bartók, Hindemith, and Casella himself. The international dimension of this prize launched Pilati’s career in the New World, and his Suite for Piano and Strings was performed in Philadelphia and Boston. Pilati taught harmony, counterpoint and composition at the Conservatories of Naples and Palermo, while he kept performing and composing. His activity continued feverishly until his premature death, which coincided with the outbreak of World War II: among its casualties, the loss of the Ricordi Archive caused also the loss of the score of his Flute Sonata, which fell into oblivion. Its manuscripts have been fortunately recovered by Pilati’s daughters who patiently and determinedly sought them, even when all hopes to recover the score had been lost. The championing of the newly found work by great flutists such as Emmanuel Pahud has given back to Pilati the place of pre-eminence his music deserves in the flute repertoire; he joins Moyse who had played it with Casella many decades earlier, and so the circle of this album closes.

01. Sonata for Flute and Piano No.1 in A Major: I. Modéré – Allegretto vivo

02. Sonata for Flute and Piano No.1 in A Major: II. Lent – Allegretto moderato - Lent

03. Sonata for Flute and Piano No.1 in A Major: III. Allegro moderato – Modéré

04. Sicilenne et Burlesque in F-Sharp Major, Op. 23: I. Sicilienne

05. Sicilenne et Burlesque in F-Sharp Major, Op. 23: II. Burlesque

06. Sonata for Flute and Piano, Op. 52: I. Adagio molto tranquillo

07. Sonata for Flute and Piano, Op. 52: II. Allegretto très modéré mais sans trainer

08. Sonata for Flute and Piano, Op. 52: III. Animé et gai – Allegro con moto

09. Sonata for Flute and Piano: I. Allegro moderato

10. Sonata for Flute and Piano: II. Lento e sostenuto

11. Sonata for Flute and Piano: III. Lievemente mosso

Less than one decades divides the oldest from the most recent work recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album, which explores the repertoire for flute and piano written between 1917 and 1926. Two of the composers featured here were Frenchmen, two Italians – although one of them, Alfredo Casella, can be considered as almost French by virtue of his musical education.

In spite of the brief timespan covered by this recording, it also exemplifies the style and musical thought of two distinct generations. Charles Koechlin, the eldest composer represented here, was born in 1867, while Mario Pilati, the youngest, could have been his son, having been born in 1903. On the other hand, Pilati was the first among these four to pass away, at the young age of 35, in 1938; Koechlin would die twelve years later, at 73, in 1950.

The early life of Philippe Gaubert has something of the Romantic novel, even though the suffering it involved was very much real. Gaubert’s father was a shoemaker and an amateur clarinet player. Philippe was born in Cahors and, when the child was nine, the family moved to Paris where it was hoped the Philippe and his sibling could become professional musicians. Alas, their father died just three years later, leaving them rather destitute. In order to manage and support the household, Philippe’s mother worked as a housekeeper, and, fortunately for him, one of the homes where she worked was that of Jules Taffanel, a great flutist, and the father of an even greater flutist, Paul Taffanel. The Taffanels auditioned Philippe and were deeply impressed by his talent; Paul welcomed the boy in his class at the Conservatoire, where Philippe quickly demonstrated that their trust in him had been justified. Not only he graduated with honours at just fifteen in flute, immediately earning jobs in the most prestigious orchestras (he became first solo flutist at the Opéra orchestra in 1895), but he also studied with excellent results the violin and composition. In fact, his professor of composition was none other than Gabriel Fauré, and Gaubert showed his worth also in this field. In 1903 he got the premier prix in Fugue and Counterpoint, and two years later he nearly won the Prix de Rome. In the following years, Gaubert managed to maintain a successful career and activity in four distinct fields, in all of which he had roles of high responsibility. He was an appreciated performer, both as a flutist (although this branch of his activity was the first one to be renounced) and as a conductor; he taught extensively, transmitting the Taffanel tradition to the next generation of flutists (including among his students most notably Marcel Moyse) and conductors; he was in charge of important institutions (the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire and the Opéra); and, besides this all, he found time for composing numerous works which are today among his most important legacies (together with a method for flute playing which is still extremely valuable). Many of his works are written for the flute, even though the vastity of Gaubert’s professional experiences frees him from the narrow perspective which may affect other flutist-cum-composers.

Within his output, the three Flute Sonatas occupy pride of place; they were written in 1917, 1924, and 1933. They showcase Gaubert’s signature style, with his quest for lyricism, elegance, expressivity and a direct yet refined language.

The First Sonata is meaningfully dedicated “to the memory of [his] dear mentor”, Paul Taffanel. It opens on a calm mood (Modéré), characterized by a mellow atmosphere and sound, followed by a briskier and more brilliant section in C-sharp minor. A similar alternation of moods and of different beats characterizes the second movement, which juxtaposes a slow section (Lent) to a livelier part (Allegretto moderato in the compound time). The third and last movement plays on enchantment and wonder, and opens with some unforgettable measures where the narrative dimension is very pronounced. At the end of the movement, allusions to the very beginning of the Sonata encourage a cyclical reading of this score.

Gaubert’s interest in the explorations of sound and timbre which were particularly relevant for composers of his time is evident in this Sonata, where he requires specific sound qualities: “a very clear sonority”, or “a calm and penetrating sound”. Also as concerns the musical language he demonstrates his attention to contemporaneous explorations, for instance in his use of the whole-tone scale which had been popularized by Claude Debussy, especially in his Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune where the flute has a protagonist role.

Debussy had been a reference figure also for Alfredo Casella, who had been thunderstruck precisely by his listening of the Prélude. Similar to Gaubert, also Casella had studied with Fauré at the Conservatoire, where he had arrived at age 13, just as Gaubert, from his native city of Turin, Italy. However, Casella’s time at the Conservatoire ended rather abruptly due to his clash of wills with Maurice Ravel, whose perspective he could not espouse.

Casella considered himself therefore as mainly self-taught, but this did not prevent him from debuting with an ambitious work, a Symphony (1905) which he personally conducted in Monte Carlo three years later. During First World War, Casella returned to his homeland where he embarked in a successful career as a pianist (also in chamber music, having founded the extremely prestigious Trio Italiano together with Arturo Bonucci and Alberto Poltronieri), conductor, teacher of piano and composition, and organizer (he had created an important Society for the performance of contemporary music). His gaze was not turned only to the future, though; he was also deeply interested in the recovery of music of the past, particularly from Italy; he promoted the rediscovery of works by Antonio Vivaldi and by the Scarlattis (Alessandro and Domenico), and he championed the music of J. S. Bach. The instructive editions he realized of works by Bach, Beethoven and many others are still commonly employed, not only in Italy. He was also an appreciated author, who wrote poetry and prose, and who created the librettos for several of his own vocal works.

His Sicilienne and Burlesque exists in two versions (op. 23 and 23a respectively), the second of which is for piano trio and follows the earlier one, for flute and piano, by three years. The original work had been created for the Conservatoire of Paris at the time of Casella’s activity in the French Capital, and was conceived – as happened to many other short masterpieces by other great composers – as a pièce de concours for the final examinations of the Conservatoire. In this piece, Casella employs a very forward-looking harmonization, with ninth-chords, which punctuate the elegant, melancholic profile of the flute’s melody. The ironic vein of this composer surfaces in the following Burlesque, where allusions to both the folk tradition and the Italian musical heritage (Scarlatti) are observed.

Charles Koechlin had been, in turn, a student of Gabriel Fauré, but also of Jules Massenet. He would later teach at the same institution, contributing to the education of Darius Milhaud and Francis Poulenc. And whereas Casella was not in agreement with Ravel, Koechlin counted the composer among his friends, founding with him the Société musicale indépendante.

As a composer, Koechlin left a very significant output, in terms of both quantity and quality. It also demonstrates his high cultural profile and his knowledge of music from all ages. Koechlin’s erudition is also abundantly shown in his treatises and monographs, including a seminal one on Gabriel Fauré and textbooks for harmony and composition, some of which are still considered as reference points.

His Sonata op. 52 is his most important gift to the flute repertoire, but, meaningfully, he deliberately titled it “for piano and flute” rather than the other way around. In fact, his piano writing is very demanding, as is immediately visible even by looking at the score, with its constant use of the three staves. His refined writing is seen in his attention for the musical shades and nuances: as he imposes a dynamic straitjacket on the performers who are required not to go beyond certain volumes of sound, he also rewards their effort with a wealth of details. This discipline is broken, however, in the last movement, which is an explosion of musical ideas and a breathtaking run. The Sonata’s mood seems to bring in front of the interior eyes of the listener a variety of panoramas, some of which are distinctly Mediterranean. This Sonata is dedicated to Jeanne Herscher-Clément, a pianist who was the first performer of the work together with Adolphe Hennebains.

Mario Pilati was another child prodigy, whose musical accomplishment was evident at fifteen. He wrote the first version of his flute sonata when still in his teens: it was a two-movement Sonatina, which would later be elaborated in the form we now know. At twenty he graduated from the Conservatory of Naples, and the following year he was already a Conservatory professor in Cagliari. However, he thirsted for more musical experiences, and thus he left his job and moved to Milan, where he worked as a composer, pianist, conductor, musical critic, and also as a private teacher: among his pupils was Gianandrea Gavazzeni. His early career was an uninterrupted chain of successes, including victories at competitions awarding prizes or teaching posts. A particularly important moment was when the revised version of his youthful flute Sonatina, now in three movements, earned the prestigious Coolidge Prize, in memory of American patroness Elizabeth Sprague-Coolidge. This award, won at just 24, put him in the company of the likes of Stravinsky, Ravel, De Falla, Bartók, Hindemith, and Casella himself. The international dimension of this prize launched Pilati’s career in the New World, and his Suite for Piano and Strings was performed in Philadelphia and Boston. Pilati taught harmony, counterpoint and composition at the Conservatories of Naples and Palermo, while he kept performing and composing. His activity continued feverishly until his premature death, which coincided with the outbreak of World War II: among its casualties, the loss of the Ricordi Archive caused also the loss of the score of his Flute Sonata, which fell into oblivion. Its manuscripts have been fortunately recovered by Pilati’s daughters who patiently and determinedly sought them, even when all hopes to recover the score had been lost. The championing of the newly found work by great flutists such as Emmanuel Pahud has given back to Pilati the place of pre-eminence his music deserves in the flute repertoire; he joins Moyse who had played it with Casella many decades earlier, and so the circle of this album closes.

Year 2024 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads