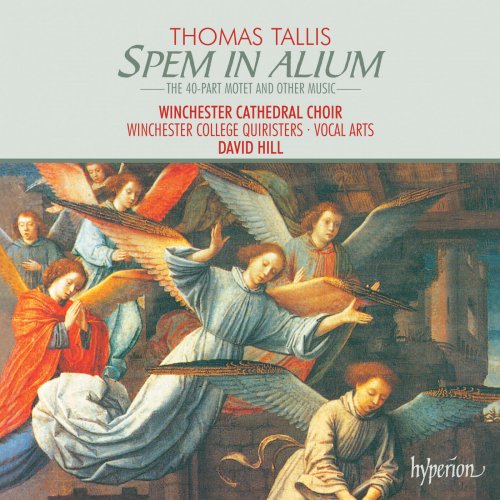

Winchester Cathedral Choir, David Hill - Tallis: Spem in alium & Other Choral Works (1990)

BAND/ARTIST: Winchester Cathedral Choir, David Hill

- Title: Tallis: Spem in alium & Other Choral Works

- Year Of Release: 1990

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 00:59:01

- Total Size: 212 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. O salutaris hostia

02. In ieiunio et fletu

03. Salvator mundi I

04. In manus tuas, Domine

05. Salvator mundi II

06. Lamentations of Jeremiah I

07. O sacrum convivium

08. O nata lux de lumine

09. Te lucis ante terminum I

10. Lamentations of Jeremiah II

11. Spem in alium

Thomas Tallis lived through some of the most stormy years of the sixteenth century. By the time of his death in 1585 he had been required to write music for Catholic rites under Henry VIII (1509–1547), for English vernacular services under Edward VI (1547–1553), for the reinstated Latin liturgy under Mary (1553–1558), and under Elizabeth I (1558–1603) both English and Latin works for her idiosyncratic approach to liturgical matters.

It was this very idiosyncracy which permitted musical experiment of a bold nature. Liturgical function in setting texts from the Catholic rite could be overlooked in the interests of through-composition, for example, or the Magnificat and Nunc dimittis for the reformed service of Evensong could actually be set in Latin. The renowned Spem in alium is a perfect example of the former technique, being liturgically a responsory from the Historia Iudith. The repeating structure of the responsory is entirely ignored, and no reference is made to its chant melody. What Tallis does is to use the text and make it into a through-composed motet, but a motet of an extraordinary kind. It is arguable that this piece in forty parts represents the epitome of choral writing in England in the sixteenth century (and not only the sixteenth): technically it is a balance between dense contrapuntal writing and homophonic declamation, exploiting every possible combination of effects available from the forty voice parts with dazzling virtuosity. It is, of course, also much more than that. It is, by turns, humble and proud, supplicatory and majestic, and always confident in its appeal to the Creator. The occasion for its composition has not been precisely identified. It may have been (among other possibilities) the fortieth birthday of either Queen Mary in 1556 or Queen Elizabeth in 1573; or possibly a piece to rival Alessandro Striggio’s own forty-part Ecce beatam lucem.

In ieiunio et fletu is a rather different composition, but has been said to be ‘possibly Tallis’s finest work’. Published in the Cantiones Sacrae of 1575, which contained music by Tallis and Byrd, In ieiunio is an astonishing matching of text to music, having absorbed much from the influx of continental music both sacred and secular into England. Chordal declamation, chromatic movement, and a careful sense of tonal architecture are the elements in the work which in combination with the more conventional polyphonic writing give a glimpse of new territory to be covered. The solemnly penitential words (‘In weeping and lamenting the priests prayed. Spare us, Lord, spare Thy people.’) give Tallis the cue to make such a complete identification with the text (and in these extremely penitential texts used by both Tallis and Byrd reference to the plight of the Catholic Church in Britain at the time is often noted) that he goes beyond his habitual technical boundaries and creates the foundations for a new vocabulary. Tallis himself took up the cue elsewhere, in his Lamentations.

The two settings of Salvator mundi are much more conventional works, though they are certainly representative of the Elizabethan period in their relative brevity and in the economy with which they make use of a restricted set of melodic and rhythmic motifs (particularly the first of the two). The second setting employs a canon between the top part and the tenor. In different ways, In manus tuas and O nata lux are both as representative of the time of Queen Elizabeth. In manus tuas is, like Spem in alium, a setting of a responsory text (this time from Compline) but in motet form, and it is one of Tallis’s most simple and straightforward Latin-texted works. The famous O nata lux, which is in fact a setting of the first two verses of a seven-verse hymn for the Feast of the Transfiguration, makes use of what could be seen as a rather histrionic harmonic vocabulary. Replete with ‘false relations’ and tonally rather indeterminate, it is one of Tallis’s most memorable works for precisely these reasons.

O salutaris hostia is a rather unrelenting piece in its construction. It is built of repetitions of sets of entries (the upper four voices often in sets of two), usually entering in descending order; and its character is in consequence a rather severe one. Much more flowing is O sacrum convivium, which was also popular as an English contrafactum ‘I call and cry’. Here there is none of the sectional construction of O salutaris, but a fluid, melodious polyphony.

Although it belongs to the pre-Reformation Sarum use, the brief Te lucis ante terminum—the Compline hymn—of which Tallis made two settings (of two different chant tunes for the text) is not too far removed in style from the Cantiones Sacrae works. Since chant tunes for hymn texts tended to be simple and syllabic, polyphonic settings of them were correspondingly less ornate than responsories, which had more elaborate chants. Tallis’s Te lucis settings have always been among his most frequently sung pieces precisely because of this simple dignity.

With the two sets of Lamentations we come to what is perhaps Tallis’s most personal music. The text is from the Maundy Thursday set, but the Lamentations can hardly have been used liturgically. Rather they are another instance of the turning of a more elaborate liturgical form into a motet. In this case there are two (separate) motets, each of several sections delineated by the ritual Hebrew letters between the Latin text. There are so many felicitous details to observe in these works—the subtle use of cumulative repetition and the ‘antiphonal’ effects between one voice and the rest also found in In ieiunio; the harmonic richness and fluidity (like that in O nata lux but stretched out over a much longer span); the melodic fecundity (particularly in the setting of the Hebrew letters)—that it is easy to overlook the carefully wrought architecture of the whole in each set. They are statements of musical and spiritual profundity such that at the conclusion—‘Ierusalem, Ierusalem, convertere ad Dominum Deum tuum’—there can be no doubt of Tallis’s intention.

01. O salutaris hostia

02. In ieiunio et fletu

03. Salvator mundi I

04. In manus tuas, Domine

05. Salvator mundi II

06. Lamentations of Jeremiah I

07. O sacrum convivium

08. O nata lux de lumine

09. Te lucis ante terminum I

10. Lamentations of Jeremiah II

11. Spem in alium

Thomas Tallis lived through some of the most stormy years of the sixteenth century. By the time of his death in 1585 he had been required to write music for Catholic rites under Henry VIII (1509–1547), for English vernacular services under Edward VI (1547–1553), for the reinstated Latin liturgy under Mary (1553–1558), and under Elizabeth I (1558–1603) both English and Latin works for her idiosyncratic approach to liturgical matters.

It was this very idiosyncracy which permitted musical experiment of a bold nature. Liturgical function in setting texts from the Catholic rite could be overlooked in the interests of through-composition, for example, or the Magnificat and Nunc dimittis for the reformed service of Evensong could actually be set in Latin. The renowned Spem in alium is a perfect example of the former technique, being liturgically a responsory from the Historia Iudith. The repeating structure of the responsory is entirely ignored, and no reference is made to its chant melody. What Tallis does is to use the text and make it into a through-composed motet, but a motet of an extraordinary kind. It is arguable that this piece in forty parts represents the epitome of choral writing in England in the sixteenth century (and not only the sixteenth): technically it is a balance between dense contrapuntal writing and homophonic declamation, exploiting every possible combination of effects available from the forty voice parts with dazzling virtuosity. It is, of course, also much more than that. It is, by turns, humble and proud, supplicatory and majestic, and always confident in its appeal to the Creator. The occasion for its composition has not been precisely identified. It may have been (among other possibilities) the fortieth birthday of either Queen Mary in 1556 or Queen Elizabeth in 1573; or possibly a piece to rival Alessandro Striggio’s own forty-part Ecce beatam lucem.

In ieiunio et fletu is a rather different composition, but has been said to be ‘possibly Tallis’s finest work’. Published in the Cantiones Sacrae of 1575, which contained music by Tallis and Byrd, In ieiunio is an astonishing matching of text to music, having absorbed much from the influx of continental music both sacred and secular into England. Chordal declamation, chromatic movement, and a careful sense of tonal architecture are the elements in the work which in combination with the more conventional polyphonic writing give a glimpse of new territory to be covered. The solemnly penitential words (‘In weeping and lamenting the priests prayed. Spare us, Lord, spare Thy people.’) give Tallis the cue to make such a complete identification with the text (and in these extremely penitential texts used by both Tallis and Byrd reference to the plight of the Catholic Church in Britain at the time is often noted) that he goes beyond his habitual technical boundaries and creates the foundations for a new vocabulary. Tallis himself took up the cue elsewhere, in his Lamentations.

The two settings of Salvator mundi are much more conventional works, though they are certainly representative of the Elizabethan period in their relative brevity and in the economy with which they make use of a restricted set of melodic and rhythmic motifs (particularly the first of the two). The second setting employs a canon between the top part and the tenor. In different ways, In manus tuas and O nata lux are both as representative of the time of Queen Elizabeth. In manus tuas is, like Spem in alium, a setting of a responsory text (this time from Compline) but in motet form, and it is one of Tallis’s most simple and straightforward Latin-texted works. The famous O nata lux, which is in fact a setting of the first two verses of a seven-verse hymn for the Feast of the Transfiguration, makes use of what could be seen as a rather histrionic harmonic vocabulary. Replete with ‘false relations’ and tonally rather indeterminate, it is one of Tallis’s most memorable works for precisely these reasons.

O salutaris hostia is a rather unrelenting piece in its construction. It is built of repetitions of sets of entries (the upper four voices often in sets of two), usually entering in descending order; and its character is in consequence a rather severe one. Much more flowing is O sacrum convivium, which was also popular as an English contrafactum ‘I call and cry’. Here there is none of the sectional construction of O salutaris, but a fluid, melodious polyphony.

Although it belongs to the pre-Reformation Sarum use, the brief Te lucis ante terminum—the Compline hymn—of which Tallis made two settings (of two different chant tunes for the text) is not too far removed in style from the Cantiones Sacrae works. Since chant tunes for hymn texts tended to be simple and syllabic, polyphonic settings of them were correspondingly less ornate than responsories, which had more elaborate chants. Tallis’s Te lucis settings have always been among his most frequently sung pieces precisely because of this simple dignity.

With the two sets of Lamentations we come to what is perhaps Tallis’s most personal music. The text is from the Maundy Thursday set, but the Lamentations can hardly have been used liturgically. Rather they are another instance of the turning of a more elaborate liturgical form into a motet. In this case there are two (separate) motets, each of several sections delineated by the ritual Hebrew letters between the Latin text. There are so many felicitous details to observe in these works—the subtle use of cumulative repetition and the ‘antiphonal’ effects between one voice and the rest also found in In ieiunio; the harmonic richness and fluidity (like that in O nata lux but stretched out over a much longer span); the melodic fecundity (particularly in the setting of the Hebrew letters)—that it is easy to overlook the carefully wrought architecture of the whole in each set. They are statements of musical and spiritual profundity such that at the conclusion—‘Ierusalem, Ierusalem, convertere ad Dominum Deum tuum’—there can be no doubt of Tallis’s intention.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads