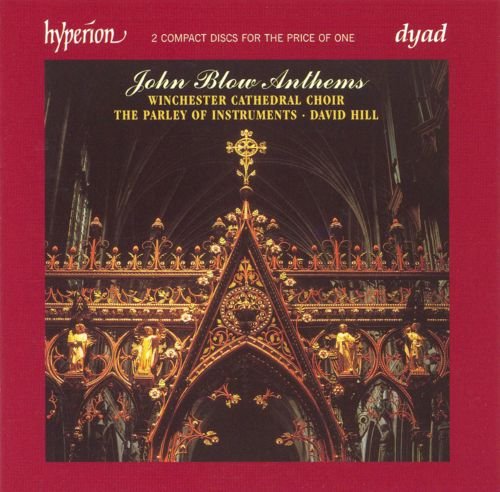

Winchester Cathedral Choir & David Hill - Blow: Anthems (2006)

BAND/ARTIST: Winchester Cathedral Choir, David Hill

- Title: John Blow: Anthems

- Year Of Release: 1995 / 2006

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: APE (image + .cue, log, artwork)

- Total Time: 01:56:23

- Total Size: 455 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

CD 1

01 God Spake Sometime in Visions for soloists, chorus & orchestra

02 How Doth the City Sit Solitary

03 The Lord is My Shepherd

04 God is our Hope and Strength

05 I Beheld, and Lo! A Great Multitude

06 Turn Thee unto Me, O Lord

07 Blessed is the Man that hath not Walked

CD 2

01 Lift up Your Heads, O Ye Gates

02 O Lord, I Have Sinned

03 O Give Thanks Unto the Lord, for He Is Gracious

04 O Lord, Thou Hast Searched Me Out and Known Me

05 Cry Aloud and Spare Not

06 Lord, Who Shall Dwell in Thy Tabernacle?

07 I Said in the Cutting Off of My Days

CD 1

01 God Spake Sometime in Visions for soloists, chorus & orchestra

02 How Doth the City Sit Solitary

03 The Lord is My Shepherd

04 God is our Hope and Strength

05 I Beheld, and Lo! A Great Multitude

06 Turn Thee unto Me, O Lord

07 Blessed is the Man that hath not Walked

CD 2

01 Lift up Your Heads, O Ye Gates

02 O Lord, I Have Sinned

03 O Give Thanks Unto the Lord, for He Is Gracious

04 O Lord, Thou Hast Searched Me Out and Known Me

05 Cry Aloud and Spare Not

06 Lord, Who Shall Dwell in Thy Tabernacle?

07 I Said in the Cutting Off of My Days

Have you ever been in the position where there was a CD or a book you intended to add to your library, but when you eventually get round to it (if you do at all), it has been withdrawn? This has been exactly my situation with this set of anthems, but in this case my sins of omission have been rewarded not with disappointment but with the wanted item landing on my doorstep as one of Hyperion’s two-for-one Dyadd reissues. The gods do occasionally smile on mere mortals.

Recorded in 1995, the set was first featured in Fanfare 19:4; indeed, it carries a blurb from J. F. Weber’s concise review to the effect that these performances “are not likely to be bettered soon.” That has proved true enough, if only because the only one of these anthems to have been recorded since is God spake sometime in visions, a large-scale piece composed for the coronation of James II in 1685, and included on Robert King’s spectacular “Coronation of George II” reconstruction (25:4). Where I do take issue with my colleague is his description of God is our hope and strength as a “full” anthem of the kind written during the reign of Charles I. In fact, while harking back to polyphonic models and owing a debt to the style, it includes a verse passage for eight soloists.

The remaining anthems fall into the category of either the “verse” type with chorus or the modern “symphony” anthem with passages for soloists and choir, prefaced by an introduction for strings (or in the case of Lord, who shall dwell? recorders and strings), and interspersed with instrumental ritornellos. Frequently, these often extended “symphonies” are notable in their own right, as in the case of The Lord is my shepherd, where the sweetness of the opening leads into a setting of Psalm 23 of great beauty, or that of Blessed is the man, with its exquisite concluding suspensions. But there is not one of these anthems as a whole that falls short of a high level of inspiration and craftsmanship, whether one considers the bold harmonic progressions and modulations (listen, for example, to the chromaticism and hovering between G Minor and D Minor in Lift up your heads), rhythmic subtlety (as in God is our hope and strength), or the numerous examples of a response to text that pronounces Blow as scarcely less a master of setting the English language than Purcell. Equally as impressive is his handling of large structures, an achievement above all notable in O give thanks, where the composer achieves a spatial effect akin to the Venetian polychoral style by laying out his verse sections for no fewer than three groups of soloists (TTB, ATB, SATB) in addition to an SATB choir, achieving an extraordinary variety of texture in the words “for his mercy endureth for ever,” which, refrain-like, pervade the psalm.

In general, I’m more than happy to endorse Weber’s high opinion of the performances, particularly with regard to the Winchester choristers and the instrumental playing. Some of the solo singing might have been more strongly projected and there’s some bleating tenor tone to be endured; but, in general, the principal imported soloists are fine, those drawn from the choir predictably less so. The boy who sings the important treble solo in Turn thee unto me (a lovely anthem) is, however, excellent; he should have been more clearly identified, though he ought to have been discouraged from singing “sowl” for “soul.”

John Blow has suffered from being a contemporary of Purcell; yet, as Peter Holman writes in his customarily scholarly note, he was unquestionably the leading Restoration church composer. This cross section of his anthems convincingly proves why. It is an important and essential addition to any collection of English church music, the 50 percent reduction in price now leaving no further excuse for anyone remotely interested in this field. -- FANFARE: Brian Robins

Recorded in 1995, the set was first featured in Fanfare 19:4; indeed, it carries a blurb from J. F. Weber’s concise review to the effect that these performances “are not likely to be bettered soon.” That has proved true enough, if only because the only one of these anthems to have been recorded since is God spake sometime in visions, a large-scale piece composed for the coronation of James II in 1685, and included on Robert King’s spectacular “Coronation of George II” reconstruction (25:4). Where I do take issue with my colleague is his description of God is our hope and strength as a “full” anthem of the kind written during the reign of Charles I. In fact, while harking back to polyphonic models and owing a debt to the style, it includes a verse passage for eight soloists.

The remaining anthems fall into the category of either the “verse” type with chorus or the modern “symphony” anthem with passages for soloists and choir, prefaced by an introduction for strings (or in the case of Lord, who shall dwell? recorders and strings), and interspersed with instrumental ritornellos. Frequently, these often extended “symphonies” are notable in their own right, as in the case of The Lord is my shepherd, where the sweetness of the opening leads into a setting of Psalm 23 of great beauty, or that of Blessed is the man, with its exquisite concluding suspensions. But there is not one of these anthems as a whole that falls short of a high level of inspiration and craftsmanship, whether one considers the bold harmonic progressions and modulations (listen, for example, to the chromaticism and hovering between G Minor and D Minor in Lift up your heads), rhythmic subtlety (as in God is our hope and strength), or the numerous examples of a response to text that pronounces Blow as scarcely less a master of setting the English language than Purcell. Equally as impressive is his handling of large structures, an achievement above all notable in O give thanks, where the composer achieves a spatial effect akin to the Venetian polychoral style by laying out his verse sections for no fewer than three groups of soloists (TTB, ATB, SATB) in addition to an SATB choir, achieving an extraordinary variety of texture in the words “for his mercy endureth for ever,” which, refrain-like, pervade the psalm.

In general, I’m more than happy to endorse Weber’s high opinion of the performances, particularly with regard to the Winchester choristers and the instrumental playing. Some of the solo singing might have been more strongly projected and there’s some bleating tenor tone to be endured; but, in general, the principal imported soloists are fine, those drawn from the choir predictably less so. The boy who sings the important treble solo in Turn thee unto me (a lovely anthem) is, however, excellent; he should have been more clearly identified, though he ought to have been discouraged from singing “sowl” for “soul.”

John Blow has suffered from being a contemporary of Purcell; yet, as Peter Holman writes in his customarily scholarly note, he was unquestionably the leading Restoration church composer. This cross section of his anthems convincingly proves why. It is an important and essential addition to any collection of English church music, the 50 percent reduction in price now leaving no further excuse for anyone remotely interested in this field. -- FANFARE: Brian Robins

Related Release:

Classical | FLAC / APE | CD-Rip

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads