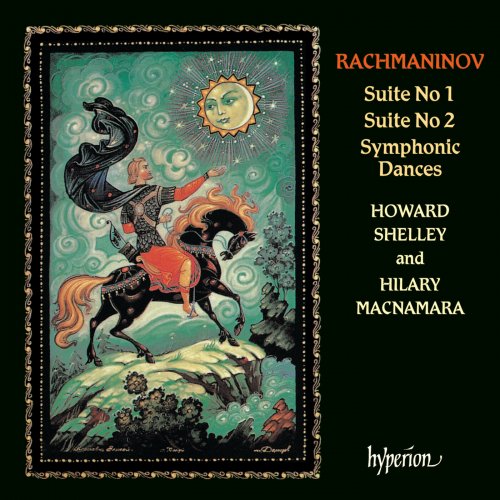

Howard Shelley, Hilary Macnamara - Rachmaninoff: Music for 2 Pianos - Suites Nos. 1 & 2; Symphonic Dances (1990)

BAND/ARTIST: Howard Shelley, Hilary Macnamara

- Title: Rachmaninoff: Music for 2 Pianos - Suites Nos. 1 & 2; Symphonic Dances

- Year Of Release: 1990

- Label: Hyperion

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 01:17:22

- Total Size: 244 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Suite No. 1 for 2 Pianos, Op. 5 "Fantaisie-tableaux": I. Barcarolle

02. Suite No. 1 for 2 Pianos, Op. 5 "Fantaisie-tableaux": II. A Night for Love

03. Suite No. 1 for 2 Pianos, Op. 5 "Fantaisie-tableaux": III. Tears

04. Suite No. 1 for 2 Pianos, Op. 5 "Fantaisie-tableaux": IV. Russian Easter

05. Suite No. 2 for 2 Pianos, Op. 17: I. Introduction. Alla marcia

06. Suite No. 2 for 2 Pianos, Op. 17: II. Waltz. Presto

07. Suite No. 2 for 2 Pianos, Op. 17: III. Romance. Andantino

08. Suite No. 2 for 2 Pianos, Op. 17: IV. Tarantella. Presto

09. Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (Version for 2 Pianos): I. Non allegro

10. Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (Version for 2 Pianos): II. Andante con moto. Tempo di valse

11. Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (Version for 2 Pianos): III. Lento assai – Allegro vivace

As a child, one of Rachmaninov’s earliest memories was of playing duets at the piano with his grandfather, Arkady Rachmaninov who, some forty years earlier, had been a pupil in Russia of the Irishman John Field. When the twelve year-old Sergei Rachmaninov became a pupil of Nikolai Zverev at the Moscow Conservatoire at the insistence of his cousin Alexander Siloti (himself a pupil of Liszt), he played two-piano transcriptions at Zverev’s home to the most eminent musicians of the day. Tchaikovsky heard the young Rachmaninov at one of these evenings and was apparently much impressed by the boy’s transcription of the older composer’s own ‘Manfred’ Symphony for piano duet; unfortunately this transcription has not survived. In the days before broadcasting and recordings of any kind, arrangements for two pianists (either at one or two pianos) were often the only means by which it was possible to become familiar with orchestral music. With Rachmaninov’s own great gifts as a pianist, it was a natural progression therefore, when his own composing inclinations became manifest, that music for this medium should have formed an important part of his expression.

As part of his composition graduation from the conservatoire in 1892 Rachmaninov composed a one-act opera, Aleko – an impressive piece for an eighteen year-old, so much so that Tchaikovsky himself used his influence greatly to further Rachmaninov’s career by endorsing the premiere of the opera at the Bolshoi in a double-bill with one of his own operas, and by encouraging the publisher Gutheil to take the younger composer’s works.

Aleko was premiered at the end of April 1893, and during the next few months Rachmaninov wrote his Fantaisie, subtitled ‘Tableaux’ – the Suite No 1 for two pianos, Op 5. Nikolai Zverev died in Moscow on 30 September 1893, and at his funeral Rachmaninov mentioned the Fantaisie to Tchaikovsky. A few days later he showed him the score and received permission to inscribe the work to Tchaikovsky after playing it through privately to him with his fellow-pupil Pavel Pabst; Tchaikovsky agreed to attend the premiere the following month to be given by Rachmaninov and Pabst, but died in St Petersburg on 25 October – the premiere was thus poignantly overshadowed. By 15 December Rachmaninov had written his second Trio élégiaque (Op 9) in Tchaikovsky’s memory; his concurrent Morceaux de salon for solo piano (Op 10) were inscribed to Pabst.

The movements of Rachmaninov’s Fantaisie (now widely known simply as Suite No 1) each carried epigraphs, and form a succession of moods, from the opening dreamy ‘Barcarolle’ to love, tears and – in the finale – joy. In a letter to his cousin Natalia Skalon during the composition of the work, Rachmaninov wrote: ‘I am occupied with a fantasy for two pianos, which consists of a series of musical pictures.’ Curiously, he also said that the third movement was inspired by funeral bells: the finale is a clattering evocation of a Russian Easter, more akin to Stravinsky’s Petrushka than to Rimsky-Korsakov’s overture, although on hearing the piece Rimsky-Korsakov suggested to Rachmaninov that the traditional chant ‘Christ is risen’ (which is incorporated in the music) should have first been stated alone. Rachmaninov stuck to his guns, claiming that in reality the chant and the sound of bells were always heard together.

Following the Op 10 Morceaux, Rachmaninov’s next work – of April 1894 – was a set of six duets, Op 11. This is an important work, and was followed by his Gypsy Fantasia, Op 12 (‘Caprice bohémien’), which appeared in full orchestral guise by September 1894. Curiously, however, Rachmaninov’s Op 12 had been written two years earlier, in the summer of 1892, for piano duet – and it quotes directly from Aleko (the story of which is on a gypsy subject). In orchestral guise the Gypsy Fantasia was dedicated to Peter Lodischensky, whose wife Anna was herself of gypsy extraction. Rachmaninov had recently met the couple, and soon became fascinated by – indeed, enamoured of – Anna; she did not fully return his affection.

But his next work, his first fully mature orchestral masterpiece, the Symphony No 1, was undoubtedly inspired by her and cryptically dedicated to ‘AL’. Written during most of 1895, the premiere, under a reputedly drunk Glazunov in 1897, was a catastrophe. The mauling Rachmaninov received at the hands of the critics led to a creative trauma, which was only overcome after a course of pioneering psychotherapy at the hands of the Moscow practitioner Dr Nikolai Dahl, who was himself an amateur musician, and the eventual dedicatee of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No 2 (Dahl, a viola player, actually played in the orchestra in later performances of this concerto).

A trip to Italy in 1900 with Chaliapin and the singer’s young wife stimulated the composer’s re-awakening imagination and, immediately upon his return, he wrote the Suite No 2 for two pianos, Op 17, the Piano Concerto No 2 and the Cello Sonata. Suite No 2 shows a marked advance over the first, attractive and characteristic though the earlier work be. The most immediately apparent aspect of the new work is its energy and tingling joie de vivre: in the opening ‘Alla marcia’ the notes cascade with almost breathless speed. This sensation of virtually limitless energy is carried over into the ‘Valse’, a scintillating movement which used frequently to be played separately. Even the warm and tender ‘Romance’ in 6/8 has an underlying sense of forward movement, and the final ‘Tarantelle’ is positively giddy, drawing this dazzling work to a precipitant close.

The success of Suite No 2 and Concerto No 2 preceded Rachmaninov’s marriage in 1902 to his cousin Natalia Satin. With his self-confidence restored, his career blossomed, both as composer and conductor. In 1904, succeeding Siloti, Rachmaninov was appointed musical director of the Bolshoi Opera in Moscow for the following season, but the abortive 1905 Revolution soon spread to the centre of every stage. Rachmaninov finished the triumphant season (which included the premieres of his own operas Francesca da Rimini and The Miserly Knight) only after considerable difficulties had been overcome, including strikes by the musicians and the corps de ballet. He refused a permanent post and eventually took his family to live in Dresden for several years before settling again in Russia.

But following the Russian Revolution in 1917, Rachmaninov, his wife and two young daughters left Russia for ever, penniless, and eventually lived most of their time in America, France and Switzerland. He virtually gave up conducting and after 1919 concentrated on building a career – which was extraordinarily successful – as a touring international piano virtuoso. In the remaining twenty-six years of his life he completed only six more compositions. The 1939/40 season marked the thirtieth anniversary of his American debut and, following the end of that season, Rachmaninov rented a summer home at Orchard Point, near Huntingdon, Long Island, New York. This home had a little summer house which was suitable for composition, and which was also furnished with a grand piano. The interest shown in him during the previous season doubtless stimulated his creativity, for his final work, the Symphonic Dances – the only work Rachmaninov wrote entirely in the United States – was originally completed on 10 August 1940, in a four-stave short score. For a long time, many thought this was the two-piano version, but it is not. From the short score, Rachmaninov completed the orchestration by 29 October, but not before a two-piano version had also been made from the short score, a version which Rachmaninov and Horowitz played together in September at the composer’s Long Island holiday home to a few friends, including the choreographer Fokine who had recently created a ballet, Paganini, from Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody, Op 43.

Fokine was fired with enthusiasm for the new Dances (one of the early working titles, along with Fantastic Dances, before the final Symphonic Dances appellation was decided upon). Originally, according to some sources, Rachmaninov wanted the subtitles ‘Morning’, ‘Noon’ and ‘Evening’ appended to the three movements, and wanted to make a ballet from the music, but Fokine died shortly afterwards. However, the dance element is endemic to the work, which – in both the orchestral and two-piano versions – took many years before becoming established. It is now an integral part of the twentieth-century repertoires of orchestras and pianists.

It is curious, however, that Rachmaninov left the work in both forms: it was not unique for him, as his Op 12 demonstrated, but his Symphony No 3 (Op 44, 1936) had been severely mauled by the critics, most of whom had completely misunderstood its Mahlerian sense of tragedy. Fearing that his Symphonic Dances might be similarly received (as indeed they were), the two-piano version would enable the proposed ballet to be rehearsed and the work itself to be played by the composer and Horowitz, a frequent visitor at Orchard Point in 1940, and with whom – in the 1943/44 season – Rachmaninov planned to give a number of two-piano recitals. Incidentally, Rachmaninov’s record company, RCA, turned down the composer’s suggestion of recording the Symphonic Dances and Suite No 2 with him and Horowitz.

But perhaps it marked a return to his earliest influences, of playing orchestral music in transcription, for his early life still meant a great deal to him. Only a few months before, he had left his daughter, her husband Boris Conus and their little son Sasha in France, now at the mercy of the invading German Nazi army. Who knows what thoughts went through the composer’s mind at this time? The music provides some clues. On the one hand, the Dances contain a number of self-quotations: most notably, just before the coda of the first section, Rachmaninov hauntingly quotes the main theme of the first movement of his Symphony No 1, at the time (1940) completely unknown to anyone apart from its composer. In the finale he quotes extensively from part of his ‘Vespers’, the All-Night Vigil of 1915, Op 37, arguably his greatest work. But on the other hand, this last work of Rachmaninov’s reveals a new and vibrant voice in his music, expressed in so truly symphonic manner as almost to deserve the title of ‘Symphony No 4’. The ‘Dies irae’, present in almost all of Rachmaninov’s orchestral works as well as in many solo piano pieces, is fleetingly quoted, but in the coda of the finale, marked ‘Alleluia’, it is swirled into silence by the virile and invigorating resolution: D minor, the ultimate tonality for this composer, triumphs over all on the hectic, tumultuous and life-asserting final pages. The music also contains elements of jazz, and the composition swaggers, supreme in its own self-confidence and burning with a fierce inner light. This is manifestly not music by a composer who had written himself out, but an indestructible and inspiriting musical statement of profound and irreducible power. Although both versions possess the same opus number, Rachmaninov originally intended the work to be an orchestral piece; but it is also true that the original two-piano version is so complete in itself, so manifestly conceived in two-piano terms, that in the duo version the work is utterly convincing and becomes arguably the greatest work for the medium written in the twentieth century.

01. Suite No. 1 for 2 Pianos, Op. 5 "Fantaisie-tableaux": I. Barcarolle

02. Suite No. 1 for 2 Pianos, Op. 5 "Fantaisie-tableaux": II. A Night for Love

03. Suite No. 1 for 2 Pianos, Op. 5 "Fantaisie-tableaux": III. Tears

04. Suite No. 1 for 2 Pianos, Op. 5 "Fantaisie-tableaux": IV. Russian Easter

05. Suite No. 2 for 2 Pianos, Op. 17: I. Introduction. Alla marcia

06. Suite No. 2 for 2 Pianos, Op. 17: II. Waltz. Presto

07. Suite No. 2 for 2 Pianos, Op. 17: III. Romance. Andantino

08. Suite No. 2 for 2 Pianos, Op. 17: IV. Tarantella. Presto

09. Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (Version for 2 Pianos): I. Non allegro

10. Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (Version for 2 Pianos): II. Andante con moto. Tempo di valse

11. Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (Version for 2 Pianos): III. Lento assai – Allegro vivace

As a child, one of Rachmaninov’s earliest memories was of playing duets at the piano with his grandfather, Arkady Rachmaninov who, some forty years earlier, had been a pupil in Russia of the Irishman John Field. When the twelve year-old Sergei Rachmaninov became a pupil of Nikolai Zverev at the Moscow Conservatoire at the insistence of his cousin Alexander Siloti (himself a pupil of Liszt), he played two-piano transcriptions at Zverev’s home to the most eminent musicians of the day. Tchaikovsky heard the young Rachmaninov at one of these evenings and was apparently much impressed by the boy’s transcription of the older composer’s own ‘Manfred’ Symphony for piano duet; unfortunately this transcription has not survived. In the days before broadcasting and recordings of any kind, arrangements for two pianists (either at one or two pianos) were often the only means by which it was possible to become familiar with orchestral music. With Rachmaninov’s own great gifts as a pianist, it was a natural progression therefore, when his own composing inclinations became manifest, that music for this medium should have formed an important part of his expression.

As part of his composition graduation from the conservatoire in 1892 Rachmaninov composed a one-act opera, Aleko – an impressive piece for an eighteen year-old, so much so that Tchaikovsky himself used his influence greatly to further Rachmaninov’s career by endorsing the premiere of the opera at the Bolshoi in a double-bill with one of his own operas, and by encouraging the publisher Gutheil to take the younger composer’s works.

Aleko was premiered at the end of April 1893, and during the next few months Rachmaninov wrote his Fantaisie, subtitled ‘Tableaux’ – the Suite No 1 for two pianos, Op 5. Nikolai Zverev died in Moscow on 30 September 1893, and at his funeral Rachmaninov mentioned the Fantaisie to Tchaikovsky. A few days later he showed him the score and received permission to inscribe the work to Tchaikovsky after playing it through privately to him with his fellow-pupil Pavel Pabst; Tchaikovsky agreed to attend the premiere the following month to be given by Rachmaninov and Pabst, but died in St Petersburg on 25 October – the premiere was thus poignantly overshadowed. By 15 December Rachmaninov had written his second Trio élégiaque (Op 9) in Tchaikovsky’s memory; his concurrent Morceaux de salon for solo piano (Op 10) were inscribed to Pabst.

The movements of Rachmaninov’s Fantaisie (now widely known simply as Suite No 1) each carried epigraphs, and form a succession of moods, from the opening dreamy ‘Barcarolle’ to love, tears and – in the finale – joy. In a letter to his cousin Natalia Skalon during the composition of the work, Rachmaninov wrote: ‘I am occupied with a fantasy for two pianos, which consists of a series of musical pictures.’ Curiously, he also said that the third movement was inspired by funeral bells: the finale is a clattering evocation of a Russian Easter, more akin to Stravinsky’s Petrushka than to Rimsky-Korsakov’s overture, although on hearing the piece Rimsky-Korsakov suggested to Rachmaninov that the traditional chant ‘Christ is risen’ (which is incorporated in the music) should have first been stated alone. Rachmaninov stuck to his guns, claiming that in reality the chant and the sound of bells were always heard together.

Following the Op 10 Morceaux, Rachmaninov’s next work – of April 1894 – was a set of six duets, Op 11. This is an important work, and was followed by his Gypsy Fantasia, Op 12 (‘Caprice bohémien’), which appeared in full orchestral guise by September 1894. Curiously, however, Rachmaninov’s Op 12 had been written two years earlier, in the summer of 1892, for piano duet – and it quotes directly from Aleko (the story of which is on a gypsy subject). In orchestral guise the Gypsy Fantasia was dedicated to Peter Lodischensky, whose wife Anna was herself of gypsy extraction. Rachmaninov had recently met the couple, and soon became fascinated by – indeed, enamoured of – Anna; she did not fully return his affection.

But his next work, his first fully mature orchestral masterpiece, the Symphony No 1, was undoubtedly inspired by her and cryptically dedicated to ‘AL’. Written during most of 1895, the premiere, under a reputedly drunk Glazunov in 1897, was a catastrophe. The mauling Rachmaninov received at the hands of the critics led to a creative trauma, which was only overcome after a course of pioneering psychotherapy at the hands of the Moscow practitioner Dr Nikolai Dahl, who was himself an amateur musician, and the eventual dedicatee of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No 2 (Dahl, a viola player, actually played in the orchestra in later performances of this concerto).

A trip to Italy in 1900 with Chaliapin and the singer’s young wife stimulated the composer’s re-awakening imagination and, immediately upon his return, he wrote the Suite No 2 for two pianos, Op 17, the Piano Concerto No 2 and the Cello Sonata. Suite No 2 shows a marked advance over the first, attractive and characteristic though the earlier work be. The most immediately apparent aspect of the new work is its energy and tingling joie de vivre: in the opening ‘Alla marcia’ the notes cascade with almost breathless speed. This sensation of virtually limitless energy is carried over into the ‘Valse’, a scintillating movement which used frequently to be played separately. Even the warm and tender ‘Romance’ in 6/8 has an underlying sense of forward movement, and the final ‘Tarantelle’ is positively giddy, drawing this dazzling work to a precipitant close.

The success of Suite No 2 and Concerto No 2 preceded Rachmaninov’s marriage in 1902 to his cousin Natalia Satin. With his self-confidence restored, his career blossomed, both as composer and conductor. In 1904, succeeding Siloti, Rachmaninov was appointed musical director of the Bolshoi Opera in Moscow for the following season, but the abortive 1905 Revolution soon spread to the centre of every stage. Rachmaninov finished the triumphant season (which included the premieres of his own operas Francesca da Rimini and The Miserly Knight) only after considerable difficulties had been overcome, including strikes by the musicians and the corps de ballet. He refused a permanent post and eventually took his family to live in Dresden for several years before settling again in Russia.

But following the Russian Revolution in 1917, Rachmaninov, his wife and two young daughters left Russia for ever, penniless, and eventually lived most of their time in America, France and Switzerland. He virtually gave up conducting and after 1919 concentrated on building a career – which was extraordinarily successful – as a touring international piano virtuoso. In the remaining twenty-six years of his life he completed only six more compositions. The 1939/40 season marked the thirtieth anniversary of his American debut and, following the end of that season, Rachmaninov rented a summer home at Orchard Point, near Huntingdon, Long Island, New York. This home had a little summer house which was suitable for composition, and which was also furnished with a grand piano. The interest shown in him during the previous season doubtless stimulated his creativity, for his final work, the Symphonic Dances – the only work Rachmaninov wrote entirely in the United States – was originally completed on 10 August 1940, in a four-stave short score. For a long time, many thought this was the two-piano version, but it is not. From the short score, Rachmaninov completed the orchestration by 29 October, but not before a two-piano version had also been made from the short score, a version which Rachmaninov and Horowitz played together in September at the composer’s Long Island holiday home to a few friends, including the choreographer Fokine who had recently created a ballet, Paganini, from Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody, Op 43.

Fokine was fired with enthusiasm for the new Dances (one of the early working titles, along with Fantastic Dances, before the final Symphonic Dances appellation was decided upon). Originally, according to some sources, Rachmaninov wanted the subtitles ‘Morning’, ‘Noon’ and ‘Evening’ appended to the three movements, and wanted to make a ballet from the music, but Fokine died shortly afterwards. However, the dance element is endemic to the work, which – in both the orchestral and two-piano versions – took many years before becoming established. It is now an integral part of the twentieth-century repertoires of orchestras and pianists.

It is curious, however, that Rachmaninov left the work in both forms: it was not unique for him, as his Op 12 demonstrated, but his Symphony No 3 (Op 44, 1936) had been severely mauled by the critics, most of whom had completely misunderstood its Mahlerian sense of tragedy. Fearing that his Symphonic Dances might be similarly received (as indeed they were), the two-piano version would enable the proposed ballet to be rehearsed and the work itself to be played by the composer and Horowitz, a frequent visitor at Orchard Point in 1940, and with whom – in the 1943/44 season – Rachmaninov planned to give a number of two-piano recitals. Incidentally, Rachmaninov’s record company, RCA, turned down the composer’s suggestion of recording the Symphonic Dances and Suite No 2 with him and Horowitz.

But perhaps it marked a return to his earliest influences, of playing orchestral music in transcription, for his early life still meant a great deal to him. Only a few months before, he had left his daughter, her husband Boris Conus and their little son Sasha in France, now at the mercy of the invading German Nazi army. Who knows what thoughts went through the composer’s mind at this time? The music provides some clues. On the one hand, the Dances contain a number of self-quotations: most notably, just before the coda of the first section, Rachmaninov hauntingly quotes the main theme of the first movement of his Symphony No 1, at the time (1940) completely unknown to anyone apart from its composer. In the finale he quotes extensively from part of his ‘Vespers’, the All-Night Vigil of 1915, Op 37, arguably his greatest work. But on the other hand, this last work of Rachmaninov’s reveals a new and vibrant voice in his music, expressed in so truly symphonic manner as almost to deserve the title of ‘Symphony No 4’. The ‘Dies irae’, present in almost all of Rachmaninov’s orchestral works as well as in many solo piano pieces, is fleetingly quoted, but in the coda of the finale, marked ‘Alleluia’, it is swirled into silence by the virile and invigorating resolution: D minor, the ultimate tonality for this composer, triumphs over all on the hectic, tumultuous and life-asserting final pages. The music also contains elements of jazz, and the composition swaggers, supreme in its own self-confidence and burning with a fierce inner light. This is manifestly not music by a composer who had written himself out, but an indestructible and inspiriting musical statement of profound and irreducible power. Although both versions possess the same opus number, Rachmaninov originally intended the work to be an orchestral piece; but it is also true that the original two-piano version is so complete in itself, so manifestly conceived in two-piano terms, that in the duo version the work is utterly convincing and becomes arguably the greatest work for the medium written in the twentieth century.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads