Tracklist:

01. Toccata avanti la Messa

02. Gaudeamus omnes

03. Missa Gaudeamus: I. Kyrie

04. Missa Gaudeamus: II. Gloria

05. Dominus vobiscum – Famulorum tuorum, quaesumus Domine

06. Lectio libri Sapientiae

07. Propter veritatem

08. Alleluia. Assumpta est Maria in caelum

09. Canzon dopo l'Epistola

10. Dominus vobiscum – In illo tempore

11. Missa Gaudeamus: III. Credo

12. Recercar dopo il Credo

13. Assumpta est Maria

14. Vidi speciosam: I. Vidi speciosam

15. Per omnia saecula – Dominus vobiscum – Vere dignum et iustum est

16. Missa Gaudeamus: IV. Sanctus

17. Missa Gaudeamus: V. Benedictus

18. Per omnia saecula – Pater noster

19. Missa Gaudeamus: VI. Agnus Dei

20. Optimam partem elegit sibi Maria

21. Vidi speciosam: II. Quae est ista

22. Dominus vobiscum – Mensae caelestis participes effecti

23. Recercar "Sancta Maria"

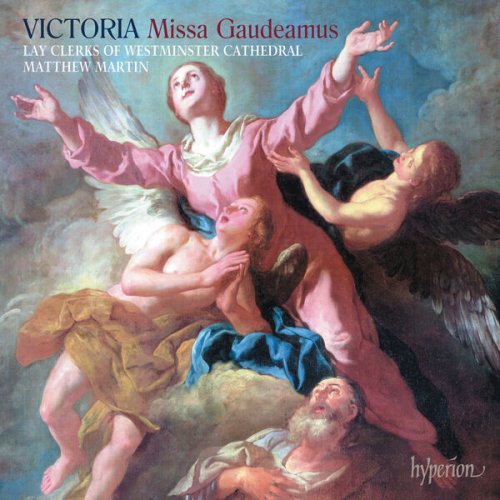

This recording by the lay clerks of Westminster Cathedral presents a full choral, and instrumental, celebration of Mass for the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which falls on 15 August. It is based on music by two major composers, Tomás Luis de Victoria and Girolamo Frescobaldi. Victoria’s Missa Gaudeamus provides the central feature of an elaborate liturgical sequence in which other music—including a motet by Victoria, Mass Propers and other passages of chant, and organ music by Frescobaldi in several forms—is interpolated between the movements of the Mass Ordinary. This festive celebration of Mass is intended not as a reconstruction of a known occasion in the early seventeenth century, but as a sort of musical offering illustrating the complex liturgical structures becoming available in a period when the resources for the enrichment of the liturgy were growing steadily.

Tomás Luis de Victoria, the greatest composer of the Spanish sixteenth-century ‘golden age’ of polyphonic music, was born in Avila in 1548 and died in Spain in 1611. In about 1558 he became a choirboy in Avila Cathedral, where he received his earliest musical training. When his voice broke he was sent to the Collegium Germanicum at Rome where he was enrolled as a student in 1565. He was to spend the next twenty years in Rome, where he occupied a number of posts of which the most important were at S Maria di Monserrato, the Collegium Germanicum, the Roman Seminary (where he succeeded Palestrina as Maestro di cappella in 1571) and S Apollinare. In 1575 he took holy orders and three years later was admitted to chaplaincy at S Girolamo della Carità. Around 1587 he left Italy and in that year took up an appointment as chaplain to the dowager Empress Maria at the Royal Convent for Barefoot Clarist Nuns, where he acted as maestro to the choir of priests and boys that was attached to the convent.

Victoria’s musical output was relatively small compared with other major Renaissance composers such as Palestrina (who published five times as much music) and Lassus (who published even more), and he published no secular music. The music he did publish, however, shows a generally very high level of inspiration and musical craftsmanship, and it is clear—from the constant revisions he made to the successive editions of his works that appeared during his lifetime and from some of his comments in prefaces to his works—that he adopted a highly critical attitude to what he wrote. In his dedication to Pope Gregory XIII of his 1581 volume of Hymni totius anni, he speaks of music being ‘an art to which I am instinctively drawn, and to the perfection of which I have devoted long years of study, with the help and encouragement of others of critical judgement’.

Victoria’s Missa Gaudeamus is based on a motet, Iubilate Deo omnis terra, by Morales which was written in 1538 to celebrate the cessation of hostilities between Francis I and Charles V as a result of mediation by the Pope, Paul III, who persuaded them to meet and sign a treaty at Nice. In the motet and the Mass both composers make much use of the opening phrase of the introit Gaudeamus omnes—‘Let us all rejoice’—as a cantus firmus, upon which to build their music. Gaudeamus omnes is a Mass Proper. Mass Propers are older forms of the Mass liturgy which vary according to the date and/or season of the liturgical calendar, and which can be interpolated between movements of the Mass Ordinary, the unvarying movements of the Mass as they were established in a later era.

Girolamo Frescobaldi was born in Ferrara in September 1583 (the exact date has not yet been established) and died in Rome on 1 March 1643. He is counted, along with Sweelinck, as one of the most influential keyboard composers of the early seventeenth century. He received youthful acclaim as an organist. His early career was in Ferrara, where the Duke Alphonso d’Este had created an impressive musical establishment, but by 1604 it is recorded that Frescobaldi had been elected to the Accademia di S Cecilia (a brotherhood of musicians in Rome) and in 1607 he became organist of S Maria in Trastevere. In 1608 he was elected organist of St Peter’s in Rome, and thereafter his fame and professional standing increased steadily both on account of his universally admired organ and harpsichord playing and, as time went on, thanks to the musical quality and style of his keyboard works. It it is now thought that his late works begin to foreshadow the style of the early Baroque period. From 1608 onwards Frescobaldi regularly published collections of his works. The publication which has attracted most attention and renown from subsequent generations is a set published in Venice in 1635, entitled Fiori musicale di diverse compositioni, tocatte, kyrie, canzone, capprici, e recercare, a 4, in partiture …. This includes three organ Masses, and it is from this publication that all the four organ interludes in the present disc have been derived.

These four pieces comprise an opening Toccata avanti la Messa, a Canzon dopo l’Epistola, a Recercar dopo il Credo and another Recercar to end the service. The toccata originated in the fifteenth century as a means of displaying impressive manual dexterity and had a loose form unbounded by the style and conventions of vocal music. The earliest printed collections of toccatas appeared in the late sixteenth century and Frescobaldi played an important part in the development of the genre. In his hands the contrasts in the passagework became more marked and the rhythms more complex, and chromaticism was sometimes introduced in place of rapid movement. The canzon, or canzona as it came to be called in Italy, originally denoted an instrumental arrangement of a polyphonic chanson; but, since the type of material chosen for such reworkings often began with passages of fugal imitation, the canzona came to be regarded as a fugal form. Certainly this is how Frescobaldi treats the Canzon dopo l’Epistola. The term recercar (Italian ‘to search’) comprehends three elements. First, the concept of musical composition being a process of searching; secondly, the idea of the recercar as a way of trying out an instrument; and thirdly the use of the form as means of exploring and displaying difficult and demanding musical structures. The latter is certainly pre-eminent in the two recercars by Frescobaldi in this recording.

After the service bell this recording opens with an organ toccata by Frescobaldi. This has a loosely organized four-part imitative structure and, after an initial flourish, begins with some gently moving passagework over a bass pedal note sustained for some four bars. This, however, is quickly superseded by a section in which the tenor introduces passages of much faster movement and greater rhythmic energy, which quickly spread to other parts. The movement is then rounded off with a final section which reverts to a more relaxed movement with much suave conjoint passagework leading to a peaceful close.

The first of the Mass Propers, the introit Gaudeamus omnes, is sung to traditional chant at the beginning of the service at the entry of the clergy. Normally the texts and melodies for different Feasts and seasons are different, but Gaudeamus omnes is an exception to this practice and the same chant is used, with minor variations of underlay, for a number of different Feasts, including All Saints Day, the Feast of the Assumption and half a dozen others.

The Kyrie, the first movement of the Mass Ordinary, is in six parts and is sung by the full choir of AATTBarB. The music immediately shows its link with the introit by using the chant and words of the first phrase of Gaudeamus omnes as a cantus firmus in the second tenor part, and with Morales’ Iubilate Deo by its employment of figures from the motet.

The Gloria, the second movement of the Mass Ordinary, again sung by the full choir, also uses the introit chant but, except in the final ‘Amen’, supplies the words from the text of the Gloria, sometimes changing the rhythym of the chant in order to do so. The Collect is a part of the service that is often read, but in this festal performance the Collect prescribed for the Feast of the Assumption is sung to traditional chant after a brief responsory. The Epistle is another part of the service commonly spoken, but here again the prescribed text, which is taken from Ecclesiasticus 24: 11–20, is sung to chant. The Gradual, the second of the Mass Propers, is here also sung to chant, the text taken from two extracts from Psalm 45. The Alleluia, another Mass Proper, opens with several florid and melismatic enunciations of ‘Alleluia’, followed by a verse referring to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary and then a repeat of the ‘Alleluias’. After a brief opening flourish, the Canzon dopo l’Epistola for organ opens with a short Adagio chordal section, which is soon followed by a brisk Allegro in an attractive and lively fugal style.

Like the Collect and Epistle, the Gospel is another part of the service that can be spoken, but here again the prescribed text, which comes from Luke 10: 38–42, is chanted. It relates the gospel tale of Martha and Mary, in which Mary sat at the feet of Christ ‘and heard his word’, but Martha, preoccupied with preparing hospitality for her illustrious guest, complained to him that Mary was not helping her. Christ replied: ‘Martha, Martha thou art careful and troubled about many things. But one thing is needful. Mary hath chosen the best part, which shall not be taken away from her.’

The Credo, the third movement of the Mass Ordinary, is sung by the full choir and again the ‘Gaudeamus’ incipit is much in evidence in many subtle variants mainly in the second tenor and baritone parts. The Recercar dopo il Credo for organ begins in fugal style with the striking entry in the top voice of an uncompromisingly angular subject which begins with an unvocal leap up a minor sixth, descends a fourth, and then continues with a five-note ascending chromatic scale. The tenor voice answers this entry with an exact imitation of it an octave lower, and the bass part then carries on the imitation a fourth below. The fugal entries are soon joined by a faster-moving passage in the alto line, a sort of ‘countersubject’ which is extensively imitated during the remaining fugal entries. It is unlikely that Ebenezer Prout, author of an illuminating nineteenth-century treatise on fugue, would have wholeheartedly approved every detail of these procedures, but it is difficult not to conclude that this style of writing by Frescobaldi points the way towards the development of the Baroque fugue. The second half of the recercar continues in a more energetic and less fugal mode, using the fugal theme several times in doubled note values in combination with much imitative passagework of a new ‘countersubject’.

Preceded by a brief responsory, the Offertory, the fourth Mass Proper, is a short prescribed text referring to the Assumption and the rejoicing of the Angels. The full choir next sings the first half of the exquisite six-part motet Vidi speciosam by Victoria, which takes its text from the first Responsory at Matins for the Feast of the Assumption. The Preface, a chanted prayer with four opening responsories, urges worshippers to lift up their hearts to God, to offer thanks to him; and to join together in praising, blessing and proclaiming the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The Sanctus, the fourth movement of the Mass Ordinary, follows, sung by the full choir. Once again the ‘Gaudeamus’ incipit in long notes is skilfully woven into the texture of the music by the second tenor and baritone voices, and, in the reduced-voice section ‘Pleni sunt caeli’, by the first tenor. The first section of the Benedictus—the fifth movement of the Mass Ordinary, also sung by the full choir—is for four voices, but the final Hosanna section is for six voices with the ‘Gaudeamus’ motif returning in the second tenor at the end.

The Pater noster, the chanted prayer ‘Our Father, which art in heaven’, is introduced with a short responsory, before the full choir sings the two Agnus Dei movements that end the Mass Ordinary. The first is in six voices; the second is in seven, having an extra baritone part to accommodate a new polyphonic device, a canon at the octave between the second alto part and the first baritone part. Both canonic parts retain the Gaudeamus omnes words sung in long notes and this and the addition of an extra voice produce imposing sonorities and a great sense of spaciousness which provide an impressive finish to the Mass.

The fifth Mass Proper, Communion, is a short chanted text referring back to the Gospel tale of Mary and Martha. This is followed by the second part of the Victoria’s motet Vidi speciosam, ‘Quae est ista’, sung by the full choir. The Post-communion is the last Mass Proper. After a brief opening responsory, the chant celebrates the Assumption and asks for the remission of sins through the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The final item in this festal celebration of Mass for the Assumption is another recercar by Frecobaldi. The organ music is in four parts with an optional extra fifth part for chant. The organ parts weave a close texture of imitative writing derived from the ‘Gaudeamus’ motif while the vocal part, using the same motif in longer notes, soars above the texture periodically enunciating the words ‘Sancta Maria, ora pro nobis’ (‘Holy Mary, pray for us’) to provide a moving conclusion to the whole Mass.