Tracklist:

01. Canzon duodecimi toni

02. Cantate Domino

03. Sacerdotes Dei

04. Missa Bell' Amfitrit' altera: I. Kyrie

05. Toccata in G

06. Missa Bell' Amfitrit' altera: II. Gloria

07. Canzona secundi toni

08. Hic est sacerdos

09. Missa Bell' Amfitrit' altera: III. Credo

10. Canzon noni toni

11. Missa Bell' Amfitrit' altera: IV. Sanctus

12. Missa Bell' Amfitrit' altera: V. Benedictus

13. Fantasia sub Elevatione

14. Missa Bell' Amfitrit' altera: VI. Agnus Dei

15. Toccata octavi toni

16. O sacrum convivium

17. Posuisti Domine

18. Canzon "La Paglia"

19. Domine Dominus noster

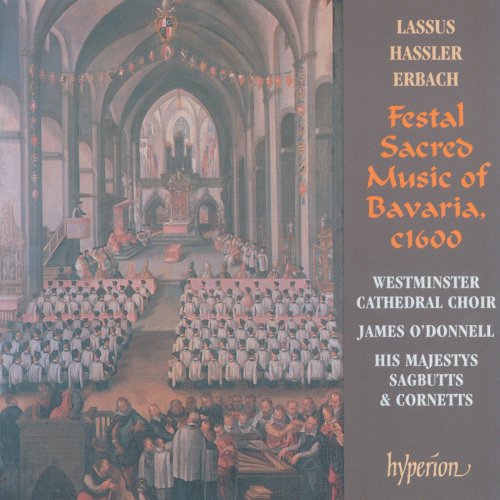

In many ways Bavaria’s most prominent musician in the later sixteenth century was not a German but the cosmopolitan Orlandus Lassus – Flemish by birth, Italian by training, and Bavarian by choice, holding the positions of singer and then Kapellmeister at the Bavarian court in Munich for nearly forty years until his death in 1594. But even during this long period at Munich he continued to travel frequently, and did much to give German music an international flavour.

The other two masters represented in this sequence of music were native Germans belonging to the next generation after Lassus. Hans Leo Hassler was, as it were, a ‘grandpupil’ of Lassus, having studied with Lassus’s pupil Leonhard Lechner. He came from Nuremberg and spent a formative period in Venice in the mid-1580s before settling down at Augsburg to work under the protection of those great patrons of the city, the Fugger family. Though a Protestant, Hassler wrote a large number of Latin settings for Catholic use.

We do not know who taught Christian Erbach, but he also was employed by the Fugger family at Augsburg, and succeeded Hassler as organist of the church of St Moritz, city organist and head of the Stadtpfeifer all at once in 1602; it is said that, since Erbach was a Catholic, the two composers had little to do with each other. In the early years of the seventeenth century Erbach became renowned for his organ playing, being appointed organist at Augsburg Cathedral, and attracted a wide range of younger German pupils from both sides of the religious divide.

The sequence of music on this record is imaginatively devised to represent what might have been heard at Mass at a festal celebration in Bavaria around 1600. The feast day is that of a martyr-bishop, since it is to that liturgy that the settings of the Proper items of the Mass by Erbach pertain. These are drawn from his first book of Modi sacri published at Augsburg in 1600. Erbach set just the Introit, Alleluia, and Communion of each Mass, so the remaining items of the Proper – Gradual and Offertory – are supplied here by pieces for organ or instruments (the substitution of instrumental pieces for sections of the Proper was quite normal at this period). The Ordinary of the Mass is sung to Lassus’s well-known eight-part setting Bell’ Amfitrit’ altera, which we thus hear as Lassus intended, its sections separated by other liturgical music. Lastly, there is a lavish provision of further works by Hassler and Erbach by way of prelude, interlude, and postlude, including an organ piece by the latter to be played during the Elevation of the Host and a motet to be sung during Communion by the former to the popular text O sacrum convivium.

Lassus’s Missa Bell’ Amfitrit’ altera was not published during his lifetime but comes from a Munich court chapel manuscript dated 1583. It is presumably based on a madrigal that has so far remained unidentified but may be Venetian, since Amphitrite was a sea-nymph. People often look in the Mass for the pure antiphonal Venetian dialogue of two divided choirs, but in fact Lassus tends to avoid these straight contrasts, preferring interplay between groups drawn from both choirs for much of the time. All this suggests that in performance Lassus did not space his choirs too far apart, as is indeed confirmed by some of the beautiful pictures of Lassus and his musicians by the court illustrator of manuscripts. For variety’s sake, Lassus writes certain short sections of the Mass for four voices only (‘Christe eleison’, ‘Crucifixus’, ‘Benedictus’) in a more flowing contrapuntal style; the return of the full choir after these passages often has an electrifying impact, and the whole work is in a bright major mode.

The Venetian note is certainly detectable in the music by Erbach and Hassler. In particular, divided choir effects appear in the vocal settings of the Proper by Erbach, and his canzona, fantasia and toccata for organ solo are strongly influenced by the Venetian organ composers. Hassler, of course, studied Venetian music at first hand, and his organ toccata owes much to the manner of the two Gabrielis. The remaining works by Hassler all come from the collection of motets and instrumental works in up to twelve parts entitled Sacri Concentus, issued at Augsburg in 1601. The opening canzona builds from contrapuntal writing to overlap and dialogue between the two groups of instruments; a dance-like section in triple time occurs twice, leading back each time to a more ornate passage in duple rhythm which exploits the wind sonorities well. The following motet for three choirs, Cantate Domino, is articulated by sonorous tuttis at appropriate words in the text, one of which (at ‘his wonders among all peoples’) is in triple time.

We hear another Hassler eight-part canzona in place of the Offertory antiphon, this time in the minor mode. From a restrained beginning this develops into a thoroughly ‘concerted’ style in which the cornett at the top of each choir has brilliant figurations in the modern Venetian manner. Particularly impressive in a different way is the communion motet O sacrum convivium for seven voices, which is written mainly in a smooth, sonorous manner until the brighter and airier texture of the final words ‘nobis pignus datur. Alleluia’.

The final Hassler motet, like Cantate Domino, is for three choirs following a characteristic Venetian disposition ‘high– middle–low’, which allows for a certain freedom in the deployment of voices and instruments, though the middle choir is indicated as the ‘capella’, or full choir. The text is the complete Psalm 8, and the fact that the psalmist reiterates the opening verse at the end gives the composer the cue for a repeat of his splendid opening tutti.