Tracklist:

01. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: I. Procession

02. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: II. Wolcom Yole!

03. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: III. There Is No Rose

04. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: IV. That Yongë Child

05. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: V. Balulalow

06. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: VI. As Dew in Aprille

07. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: VII. This Little Babe

08. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: VIII. Interlude

09. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: IX. In Freezing Winter Night

10. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: X. Spring Carol

11. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: XI. Deo gracias

12. A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28: XII. Recession

13. Missa brevis, Op. 63: I. Kyrie

14. Missa brevis, Op. 63: II. Gloria

15. Missa brevis, Op. 63: III. Sanctus & Benedictus

16. Missa brevis, Op. 63: IV. Agnus Dei

17. A Hymn to the Virgin

18. A Hymn of St Columba

19. This Way to the Tomb: Deus in adiutorium meum …

20. Jubilate Deo in E-Flat

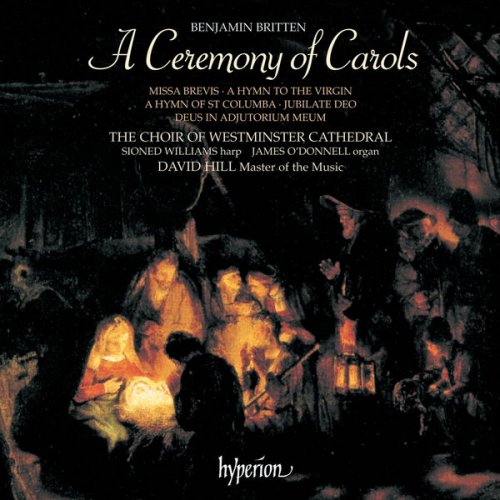

Hindsight affords us the luxury of knowing that with the appearance of Britten’s first choral publication, A Boy was Born, in 1933, a major figure in the setting of words to music had established himself. A figure, in fact, who was later to be adjudged a worthy successor to the great Henry Purcell as a setter of the English language.

If Britten’s subsequent choral works are markedly different in textures and word-settings to A Boy was Born, it must be remembered that nine years separated it from the next choral piece, A Hymn to St Cecilia, a period during which the young composer wrote his first opera, Paul Bunyon. Both the Hymn to St Cecilia and Paul Bunyon were to words by W H Auden, whose verse transformed Britten’s approach to word-setting. From this period too, came A Ceremony of Carols, giving further proof of Britten’s mastery in matching word-rhythms to melodic lines.

The works contained on this record date from 1930 to 1962, thus spanning nearly four decades that reveal the fascinating progress of a developing master of song – the greatest this country has been able to call its own for more than three hundred years.

A Ceremony of Carols, Op 28

Britten’s first work for boys’ voices was written (together with the Hymn to St Cecilia) during the composer’s perilous voyage home from America in 1942.

This cycle of medieval and sixteenth-century poems is preceded and followed by the plainsong antiphon ‘Hodie’ from the Christmas Eve Vespers, the source of some of the melodic cells used in various sections of the work. As with the earlier Hymn to the Virgin Britten clearly saw in this cycle the chance to write music that would blossom in the reverberant acoustic of church or cathedral. This may be heard in the canonic writing in ‘This little Babe’ which precipitates its vocal lines with awe-inspiring power amplified by the natural acoustic to truly dramatic effect; an effect which can scarcely be imagined from an examination of the score and a knowledge of the slender forces employed. Similarly, in ‘In freezing winter night’ the use of canonic writing greatly adds to the extraordinary atmosphere, as does Britten’s employment of plain and elaborated versions of the same melodic line which are heard simultaneously. Throughout this fifteen-minute masterpiece Britten blends elements of modal, major and minor tonalities in a wide chromatic range that achieves great variety despite the obvious limitations of compass entailed in writing for treble voices. At the centre of A Ceremony of Carols lies the ‘Interlude’ for solo harp based on the plainchant. Its bell-like harmonics and its use of the pentatonic scale inevitably remind one of the Balinese gamelan orchestra to which Britten had been introduced for the first time shortly before leaving America. Bell sounds are also to be heard in ‘Wolcum Yole!’ and ‘Adam lay i-bounden’, an idea the composer was to develop more fully in the opera Peter Grimes. Britten was not alone in his love of such sonorities; both Rachmaninov and Stravinsky, influenced no doubt by early and strong influences of the Russian Orthodox Church, professed a lifelong fascination with the sound of bells.

Missa Brevis in D, op 63

Written in 1959 for the boys of Westminster Cathedral and their then director, George Malcolm, the Missa Brevis is one of Britten’s first works to a Latin text. Not being a ‘living’ language it cannot be expected that even Britten could set Latin with the freedom that he brought to English, French and Italian; instead he employs his Latin texts as ‘phonetic material’, rather in the manner of Stravinsky. That said, this little work is an undoubted masterpiece which somehow manages to relate the character of his music for children with proper observance of the liturgy.

George Malcolm’s training had produced a singular timbre in the boys’ choir quite different from the bland tone of the ‘cathedral’ tradition. This timbre, which had the ‘edge’ of a wind instrument, allowed Britten to use the voice parts in an instrumental manner that is as refreshing as it is delightful. The work involves much organization of motifs; for example the Kyrie begins with an inversion of the Gloria’s plainsong intonation and is an impassioned plea for peace. The Gloria is set in a lively 7/8 rhythm first heard in the organ pedals before being taken up by the singers. The plainsong phrase is punctuated by bar-long chords and there is an interesting flowing scalewise tune heard first at ‘Qui tollis peccata mundi’.

The bell-like Sanctus is a marvellous example of Britten’s aural imagination with its climactic ‘Hosanna’, and the preceding passage of triplets at ‘Pleni sunt caeli et terra gloria tua’ written so knowingly for a cathedral acoustic. The following Benedictus immediately establishes a profoundly moving mood of quiet fervour before the final outburst of ‘Hosanna’. The Agnus Dei is an agonized prayer for peace in which the voices’ short phrases are pitted against an insistent ostinato pedal and dissonant chords from the organ’s manuals. The work ends as if the world were exhausted in its search for peace.

A Hymn to the Virgin

In A Hymn to the Virgin Britten perhaps comes nearest to the traditional conception of English church music. Based on an anonymous text its antiphonal echo effects and regular bar-groups invest this delightful little work with a naïve and gentle form of expression that is direct in its appeal and totally persuasive in its language. It dates from 1930, a notable offering from a composer on the very threshold of his career.

A Hymn of St Columba (Regis regum rectissimi)

The words of this hymn are attributed to St Columba (521-597) and Britten’s setting of them dates from the very last days of 1962. The work is simple in the best sense of the term. Its craftsmanship is as unerring as is its sensitivity to the text. St Columba was founder of the monastery of Iona and from the island shrine he made missionary journeys to the Highlands of Scotland.

Deus in adjutorium meum

From 1934 to 1939 incidental music for films and radio plays were significant in Britten’s early development of certain creative disciplines. At the end of the war the composer again interested himself in incidental music, collaborating with Ronald Duncan in the latter’s This Way to the Tomb (1945). (It was the same author who, at about the same time, adapted André Obey’s treatment of the Lucretia legend for the chamber opera The Rape of Lucretia.) This Way to the Tomb is divided into two parts, Masque and Antimasque, and whilst the Antimasque has been described as satirical to a point of amiable banality, the music for the Masque is all vocal, much of it choral, and includes the setting, here recorded, of Psalm 70, ‘Deus in adjutorium meum …’, for unaccompanied voices.

Jubilate Deo in E Flat

This setting of the 100th Psalm was written in August 1934 and intended as a companion piece to the Te Deum in C which preceded it by some three weeks. Britten decided against publishing this first Jubilate setting and it did not appear in print until 1984. The composer had, however, produced a second Jubilate setting in 1961 at the request of the Duke of Edinburgh.

The original Te Deum of 1934 has been described by Peter Evans as ‘self-consciously economical’ and earlier by Constant Lambert as ‘drab and penitential’. Such criticisms could scarcely be applied to the Jubilate Deo which already bears the imprint of a genius at word-setting and contains several characteristic harmonic shifts to intrigue the ear.