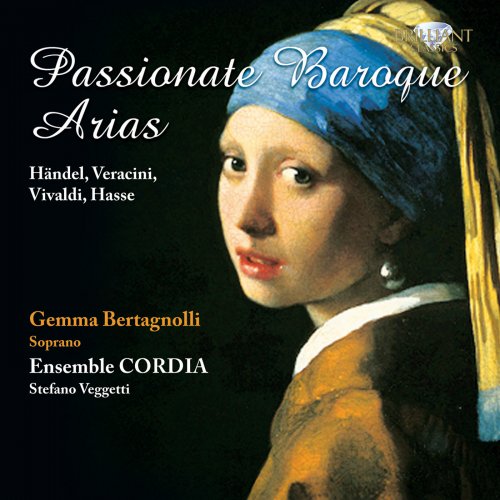

Gemma Bertagnolli, Ensemble Cordia, Stefano Veggetti - Passionate Baroque Arias (2010)

BAND/ARTIST: Gemma Bertagnolli, Ensemble Cordia, Stefano Veggetti

- Title: Passionate Baroque Arias

- Year Of Release: 2010

- Label: Brilliant Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks) +Booklet

- Total Time: 00:52:21

- Total Size: 228 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Astarto: Sinfonia. Allegro

02. Il trionfo del Tempo e del disinganno, HWV 46a

03. Watermusic, Suite in F Major, HWV 348: Minuetto

04. Adriano in Siria

05. Watermusic Suite in F Major, HWV 348: Without Title Information

06. L'olimpiade, RV 725: Lo seguitai felice

07. Concerto Grosso, Op. 6 No. 6, HWV 324: Affetuoso, Allegro ma non troppo

08. Concerto grosso, Op. 3 No. 2, HWV 313: Andante

09. Arianna in Creta, HWV 32: Son qual stanco pellegrino

10. Concerto in F-Dur, RV 538: Largo

11. Rodelinda, HWV 19: Ritorna, caro dolce mio tesoro

12. Giulio Cesare, HWV 17: Sinfonia

13. Orlando finto pazzo, RV 727: La speranza verdeggiando

14. Trionfo del Tempo e del disinganno, HWV 46a: Tu del ciel Ministro eletto

In 18th-century Italian opera the solo aria – a form of musical expression held in high favour by Humanist culture (owing to its close link with the word) – was the main, indeed almost the exclusive, vehicle for expressing the characters’ feelings and emotions. And the presentation of different expressive situations is surely one of the most characteristic features of Italian opera. Unlike its French counterpart, Italian opera showed little interest in any kind of realistic representation of the plot. Instead it focused on the music. Or more specifically, it concentrated on the capacity of the human voice to arouse emotions, of which love is naturally one of the most frequently encountered. As a result, the diverse facets of love (right down to its idealization or to its sacrifice for reasons of state) form the standard fare of opera plots.

It is something of a commonplace to consider 18th-century opera as little more than a battleground for the display of virtuoso singers. But it would be truer to say that the singers became the unchallenged masters of the opera stage precisely because their superb technique and vocal skills made it possible to highlight the emotions and give musical life to the ‘affects’; in other words, to the different states of mind of the various characters. It is no coincidence that the very etymology of the term ‘aria’ (from the Latin aer) is linked to the concept of a musical ‘mode’, in the sense of a ‘manner of singing’.

01. Astarto: Sinfonia. Allegro

02. Il trionfo del Tempo e del disinganno, HWV 46a

03. Watermusic, Suite in F Major, HWV 348: Minuetto

04. Adriano in Siria

05. Watermusic Suite in F Major, HWV 348: Without Title Information

06. L'olimpiade, RV 725: Lo seguitai felice

07. Concerto Grosso, Op. 6 No. 6, HWV 324: Affetuoso, Allegro ma non troppo

08. Concerto grosso, Op. 3 No. 2, HWV 313: Andante

09. Arianna in Creta, HWV 32: Son qual stanco pellegrino

10. Concerto in F-Dur, RV 538: Largo

11. Rodelinda, HWV 19: Ritorna, caro dolce mio tesoro

12. Giulio Cesare, HWV 17: Sinfonia

13. Orlando finto pazzo, RV 727: La speranza verdeggiando

14. Trionfo del Tempo e del disinganno, HWV 46a: Tu del ciel Ministro eletto

In 18th-century Italian opera the solo aria – a form of musical expression held in high favour by Humanist culture (owing to its close link with the word) – was the main, indeed almost the exclusive, vehicle for expressing the characters’ feelings and emotions. And the presentation of different expressive situations is surely one of the most characteristic features of Italian opera. Unlike its French counterpart, Italian opera showed little interest in any kind of realistic representation of the plot. Instead it focused on the music. Or more specifically, it concentrated on the capacity of the human voice to arouse emotions, of which love is naturally one of the most frequently encountered. As a result, the diverse facets of love (right down to its idealization or to its sacrifice for reasons of state) form the standard fare of opera plots.

It is something of a commonplace to consider 18th-century opera as little more than a battleground for the display of virtuoso singers. But it would be truer to say that the singers became the unchallenged masters of the opera stage precisely because their superb technique and vocal skills made it possible to highlight the emotions and give musical life to the ‘affects’; in other words, to the different states of mind of the various characters. It is no coincidence that the very etymology of the term ‘aria’ (from the Latin aer) is linked to the concept of a musical ‘mode’, in the sense of a ‘manner of singing’.

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads