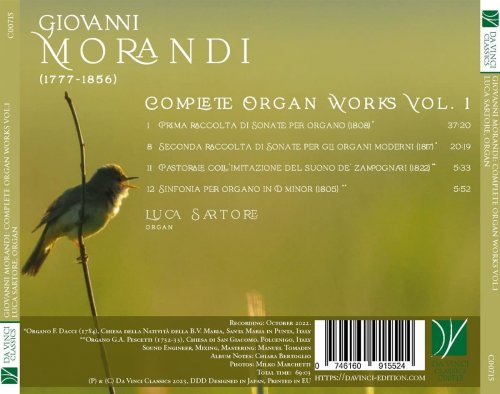

Luca Sartore - Morandi: Complete Organ Works Vol. 1 (2023)

BAND/ARTIST: Luca Sartore

- Title: Morandi: Complete Organ Works Vol. 1

- Year Of Release: 2023

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 69:09 min

- Total Size: 347 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Prima raccolta di Sonate per organo in C Major: 1. Sonata prima (Sinfonia per imitazione di flauto e fagotto)

02. Prima raccolta di Sonate per organo in E-Flat Minor: 2. Sonata seconda

03. Prima raccolta di Sonate per organo in G Major: 3. Sonata terza

04. Prima raccolta di Sonate per organo in D Major: 4. Sonata quarta

05. Prima raccolta di Sonate per organo in F Major: 5. Sonata quinta (Adagio per imitazione dell’oboè)

06. Prima raccolta di Sonate per organo in C Major: 6. Sonata sesta

07. Prima raccolta di Sonate per organo in G Major: 7. Sonata settima

08. Seconda raccolta di Sonate per gli organi moderni in C Major: 1. Sonata prima (Sinfonia con l’imitazione di Grand’Orchestra)

09. Seconda raccolta di Sonate per gli organi moderni in A Minor: 2. Sonata seconda (Adagio con l’imitazione di Voce Umana)

10. Seconda raccolta di Sonate per gli organi moderni in F Major: 3. Sonata terza (Introduzione,Tema con variazioni e Finale con l’imi

11. Pastorale coll’imitazione del suono de’ zampognari

12. Sinfonia per organo in D Minor

The figure of Giovanni Morandi has an established fame within the circles of organists, organ specialists and organ lovers, but little known outside them. And it is a pity, since his personality and works constitute a fundamental stage in the development of Italian organ music, bridging the gap between the towering figure of Frescobaldi, in the early Baroque, and the great musicianship of Marco Enrico Bossi, at the end of the nineteenth century. Along with Padre Davide da Bergamo, another great organist and composer who lived at approximately the same time, Morandi is therefore a major representative of the early-nineteenth-century Italian organ school.

His life can be divided into three major stages, and the transition between the one and the other is always marked and determined by the figure of his wife: a first stage before their wedding, a second coinciding with their years together, and a third after her death.

In the first period of Morandi’s life, he grew up under the wings of his father Pietro (1745-1815), who taught singing at the highest level; among his students were some star singers of the era. Pietro’s refined musicianship is testified also by his membership in the prestigious Accademia Filarmonica of Bologna and by his studies with Padre Martini. Giovanni followed in his father’s footsteps as a teacher of singing, and, in this capacity, he met with Rosa Paolina Morolli, a student of his, who later became his wife. Rosa was an exceptional singer, and, as was usual at the time, her husband accompanied her in her concert tours. During these journeys and the stays these involved, Giovanni taught singing and absorbed the musical life of the towns, cities and countries they were visiting. He worked as a pianist at the Théâtre Italien in Paris, and was in close correspondence with the greatest composers of the era (such as J. S. Mayr, F. S. Mercadante, J. Meyerbeer, G. Rossini or G. Spontini) and with other intellectuals and artists, particularly in the operatic field. During this second stage of his life, Morandi tried his hand in turn in the operatic field, composing comic operas and intermezzi. According to one biographer, moreover, the Morandis were responsible for Gioachino Rossini’s first major engagements: having known him (who had been recommended to them by his mother, in a typically Italian fashion!) and appreciated his genius and skill, they spoke of him to an impresario in Venice. Rossini was immediately invited to join them there, and his opera La cambiale di matrimonio was scheduled for performance. Still, the singers were not always happy with Rossini’s innovative choices, and the young composer was intensely frustrated by their demands. Once more, the Morandis came to his rescue, helping him to reshape some passages without substantially altering the originality of his style.

During this period as “Rosa’s husband”, Morandi also began his friendship and correspondence with Giovanni Ricordi, the most important Italian music publisher of the time, the one who shaped the tastes and careers of the Italian musical scene, and a personality who clearly influenced the lives and choices of countless musicians.

This would prove providential in the subsequent years. With Rosa’s death, after twenty years of married life, Giovanni’s tours came to an abrupt end. He retired in Senigallia, a beautiful town in the Marche, by the Adriatic Sea. The city, in spite of its small size, had a lively musical scene; in spite of this, however, Morandi’s life could have been harshly limited by his choice to remain there, had he not built such a large network of acquaintances and friendships throughout Europe. On the one hand, therefore, Morandi became the soul and life of Senigallia, not only within the strictly musical field; on the other, he was kept up to date with the major developments of the great cities thanks to his correspondents. Moreover, his own works kept being published by Ricordi, who also efficaciously promoted them.

Among his manifold activities, in the last three decades of his long life, were a music shop (which revived an initiative first created by his father Pietro), the role of Chapel Master at the local Cathedral Church, and the founding and directing of a music society by the bizarre name of Società dei Filomusicori. Its foundation had been prompted by the local bishop, who was a music lover, and it allowed both Morandi and the city where he lived to enjoy first-class music.

As briefly hinted, Morandi’s involvement in his city’s life was not limited to music; he was also entrusted with roles in civic administration. His main activities, though, remained bound to the musical sphere, and involved composing, teaching, and also the evaluations of organs. He was in close contact with some female monasteries in the city area. For the nuns he wrote a very substantial corpus of sacred works, which still remain largely in the manuscript form, and have been preserved by the nuns for their own musical activities. The published part of his output, instead, circulated internationally, thanks to the good offices of the companies issuing his works, and which included some major houses of the era: from André to Lucca and Ricordi.

Among his published works, the largest portion is by far that dedicated to organ music, and this has been crucial for shaping the reception of Morandi’s personality and music. However, and even though the unpublished component is hard to estimate, these proportions do not match reality as concerns the actual size of his compositional output.

An aspect worth mentioning, however, in his organ music is its remarkable and substantial stability. While the composer’s life was clearly marked by a “before” and an “after”, with respect to his wedding and to his wife’s death, this discontinuity is not observed in his organ output. For almost five decades, Morandi kept issuing organ works, in a fascinating and continuous flow which rightly earned him pride of place among the organ composers of the era.

There is however a difference in terms of genre as concerns his published and unpublished organ output. Among the works which still remain in the manuscript form, there are opera arrangements and Military Marches, side by side with more “serious” works such as Sonatas or Pastorales. Paradoxically, the presence of “lighter” music betrays the destination of these works for the female convents. In fact, opera paraphrases and the likes were conceived for the nuns’ recreation, an exquisitely private activity inside the monastery. On the other hand, in his published output Morandi was careful to avoid the infiltration of operatic gestures and styles, even though his stance was not the most common among his contemporaries. Significantly, Ricordi wrote to Morandi praising precisely his refusal to acquiesce to the trivialization of sacred music which so many coeval composers happily and thoughtlessly practised.

His organ Sonatas were mainly published as collections (“Raccolte”). The pieces they gathered were normally grouped by threes (a triplet or more than one), mirroring the liturgical destination of these Sonatas. They had been conceived for worship, in fact, and consisted of a quick movement, envisioned for the liturgical moment of Offertory, a contemplative slow movement for the all-important moment of Elevation, and a briskly-paced Post Communio, which closed the worship in the fashion of a brilliant Voluntary.

If the influence of opera was carefully kept at bay by Morandi at the most superficial (but also at the most audible) level of music, this could not be said of form. In this case, in fact, there is a clear derivation of many movements written by Morandi from the Rossini-like opening “Symphony”. The presence of distinguishable patterns of thought and musical concept is observed also as regards registration choices. The Sonatas’ first movements are reminiscent of the Baroque scheme Solo/Tutti, which (here as in a Vivaldi concerto!) is employed in order to articulate the formal structure and to put the solos into appropriate relief. Given the liturgical and spiritual importance of the moment, the pieces written for Elevation are characterized by the contemplative sound of the Vox Humana, as if suggesting the amazed enchantment of the human souls in front of the mystery of incarnation and transubstantiation. The finales are treated as a unity, with normally a single indication for registration.

In terms of organ sound, indeed, Morandi was clearly influenced in his compositional choices by the availability of organs built by Gaetano Callido, from the region of Veneto, but whose works are found throughout the region of the Marche where Morandi lived.

Another trait found in Morandi’s works less frequently than in those of his contemporaries is the use of imitations of orchestral sounds. In this Da Vinci Classics album we find some significant but relatively sparse occurrences of this fashion which was highly practised by Morandi’s contemporaries. For instance, the first C-major Sonata from Book One is a Symphony with imitation of flute and bassoon, and the F-major sonata from the same Book is an Adagio imitating an oboe. In the second Collection (1817) this mania is indulged a little more, in the first movement of the C-major Sonata (Symphony imitating a large orchestra), in the A-minor Adagio (“imitating the human voice”), and in the third Sonata, in F Major, whose Finale offers the imitation of a full orchestra. Also in the Pastorale, we find the (not uncommon) attempt to imitate the bagpipers’ music, signifying their adoration of the Child Jesus. This tendency, which is still observable in these collections, would become decreasingly common in Morandi’s works written after 1824. Similarly, even though his Pastorali frequently embody dance movements or hints to dance, they are by no means comparable with the distinctly jumpy gestures of genuine dance movements which found their way in worship music written by some of his contemporaries.

Morandi’s works, therefore, reveal their composer as someone who was passionate about proper sacred music, and who was able to find the delicate balance between variety and soberness, brilliance and equilibrium, fascination, enchantment and rationality.

Chiara Bertoglio

His life can be divided into three major stages, and the transition between the one and the other is always marked and determined by the figure of his wife: a first stage before their wedding, a second coinciding with their years together, and a third after her death.

In the first period of Morandi’s life, he grew up under the wings of his father Pietro (1745-1815), who taught singing at the highest level; among his students were some star singers of the era. Pietro’s refined musicianship is testified also by his membership in the prestigious Accademia Filarmonica of Bologna and by his studies with Padre Martini. Giovanni followed in his father’s footsteps as a teacher of singing, and, in this capacity, he met with Rosa Paolina Morolli, a student of his, who later became his wife. Rosa was an exceptional singer, and, as was usual at the time, her husband accompanied her in her concert tours. During these journeys and the stays these involved, Giovanni taught singing and absorbed the musical life of the towns, cities and countries they were visiting. He worked as a pianist at the Théâtre Italien in Paris, and was in close correspondence with the greatest composers of the era (such as J. S. Mayr, F. S. Mercadante, J. Meyerbeer, G. Rossini or G. Spontini) and with other intellectuals and artists, particularly in the operatic field. During this second stage of his life, Morandi tried his hand in turn in the operatic field, composing comic operas and intermezzi. According to one biographer, moreover, the Morandis were responsible for Gioachino Rossini’s first major engagements: having known him (who had been recommended to them by his mother, in a typically Italian fashion!) and appreciated his genius and skill, they spoke of him to an impresario in Venice. Rossini was immediately invited to join them there, and his opera La cambiale di matrimonio was scheduled for performance. Still, the singers were not always happy with Rossini’s innovative choices, and the young composer was intensely frustrated by their demands. Once more, the Morandis came to his rescue, helping him to reshape some passages without substantially altering the originality of his style.

During this period as “Rosa’s husband”, Morandi also began his friendship and correspondence with Giovanni Ricordi, the most important Italian music publisher of the time, the one who shaped the tastes and careers of the Italian musical scene, and a personality who clearly influenced the lives and choices of countless musicians.

This would prove providential in the subsequent years. With Rosa’s death, after twenty years of married life, Giovanni’s tours came to an abrupt end. He retired in Senigallia, a beautiful town in the Marche, by the Adriatic Sea. The city, in spite of its small size, had a lively musical scene; in spite of this, however, Morandi’s life could have been harshly limited by his choice to remain there, had he not built such a large network of acquaintances and friendships throughout Europe. On the one hand, therefore, Morandi became the soul and life of Senigallia, not only within the strictly musical field; on the other, he was kept up to date with the major developments of the great cities thanks to his correspondents. Moreover, his own works kept being published by Ricordi, who also efficaciously promoted them.

Among his manifold activities, in the last three decades of his long life, were a music shop (which revived an initiative first created by his father Pietro), the role of Chapel Master at the local Cathedral Church, and the founding and directing of a music society by the bizarre name of Società dei Filomusicori. Its foundation had been prompted by the local bishop, who was a music lover, and it allowed both Morandi and the city where he lived to enjoy first-class music.

As briefly hinted, Morandi’s involvement in his city’s life was not limited to music; he was also entrusted with roles in civic administration. His main activities, though, remained bound to the musical sphere, and involved composing, teaching, and also the evaluations of organs. He was in close contact with some female monasteries in the city area. For the nuns he wrote a very substantial corpus of sacred works, which still remain largely in the manuscript form, and have been preserved by the nuns for their own musical activities. The published part of his output, instead, circulated internationally, thanks to the good offices of the companies issuing his works, and which included some major houses of the era: from André to Lucca and Ricordi.

Among his published works, the largest portion is by far that dedicated to organ music, and this has been crucial for shaping the reception of Morandi’s personality and music. However, and even though the unpublished component is hard to estimate, these proportions do not match reality as concerns the actual size of his compositional output.

An aspect worth mentioning, however, in his organ music is its remarkable and substantial stability. While the composer’s life was clearly marked by a “before” and an “after”, with respect to his wedding and to his wife’s death, this discontinuity is not observed in his organ output. For almost five decades, Morandi kept issuing organ works, in a fascinating and continuous flow which rightly earned him pride of place among the organ composers of the era.

There is however a difference in terms of genre as concerns his published and unpublished organ output. Among the works which still remain in the manuscript form, there are opera arrangements and Military Marches, side by side with more “serious” works such as Sonatas or Pastorales. Paradoxically, the presence of “lighter” music betrays the destination of these works for the female convents. In fact, opera paraphrases and the likes were conceived for the nuns’ recreation, an exquisitely private activity inside the monastery. On the other hand, in his published output Morandi was careful to avoid the infiltration of operatic gestures and styles, even though his stance was not the most common among his contemporaries. Significantly, Ricordi wrote to Morandi praising precisely his refusal to acquiesce to the trivialization of sacred music which so many coeval composers happily and thoughtlessly practised.

His organ Sonatas were mainly published as collections (“Raccolte”). The pieces they gathered were normally grouped by threes (a triplet or more than one), mirroring the liturgical destination of these Sonatas. They had been conceived for worship, in fact, and consisted of a quick movement, envisioned for the liturgical moment of Offertory, a contemplative slow movement for the all-important moment of Elevation, and a briskly-paced Post Communio, which closed the worship in the fashion of a brilliant Voluntary.

If the influence of opera was carefully kept at bay by Morandi at the most superficial (but also at the most audible) level of music, this could not be said of form. In this case, in fact, there is a clear derivation of many movements written by Morandi from the Rossini-like opening “Symphony”. The presence of distinguishable patterns of thought and musical concept is observed also as regards registration choices. The Sonatas’ first movements are reminiscent of the Baroque scheme Solo/Tutti, which (here as in a Vivaldi concerto!) is employed in order to articulate the formal structure and to put the solos into appropriate relief. Given the liturgical and spiritual importance of the moment, the pieces written for Elevation are characterized by the contemplative sound of the Vox Humana, as if suggesting the amazed enchantment of the human souls in front of the mystery of incarnation and transubstantiation. The finales are treated as a unity, with normally a single indication for registration.

In terms of organ sound, indeed, Morandi was clearly influenced in his compositional choices by the availability of organs built by Gaetano Callido, from the region of Veneto, but whose works are found throughout the region of the Marche where Morandi lived.

Another trait found in Morandi’s works less frequently than in those of his contemporaries is the use of imitations of orchestral sounds. In this Da Vinci Classics album we find some significant but relatively sparse occurrences of this fashion which was highly practised by Morandi’s contemporaries. For instance, the first C-major Sonata from Book One is a Symphony with imitation of flute and bassoon, and the F-major sonata from the same Book is an Adagio imitating an oboe. In the second Collection (1817) this mania is indulged a little more, in the first movement of the C-major Sonata (Symphony imitating a large orchestra), in the A-minor Adagio (“imitating the human voice”), and in the third Sonata, in F Major, whose Finale offers the imitation of a full orchestra. Also in the Pastorale, we find the (not uncommon) attempt to imitate the bagpipers’ music, signifying their adoration of the Child Jesus. This tendency, which is still observable in these collections, would become decreasingly common in Morandi’s works written after 1824. Similarly, even though his Pastorali frequently embody dance movements or hints to dance, they are by no means comparable with the distinctly jumpy gestures of genuine dance movements which found their way in worship music written by some of his contemporaries.

Morandi’s works, therefore, reveal their composer as someone who was passionate about proper sacred music, and who was able to find the delicate balance between variety and soberness, brilliance and equilibrium, fascination, enchantment and rationality.

Chiara Bertoglio

Year 2023 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads