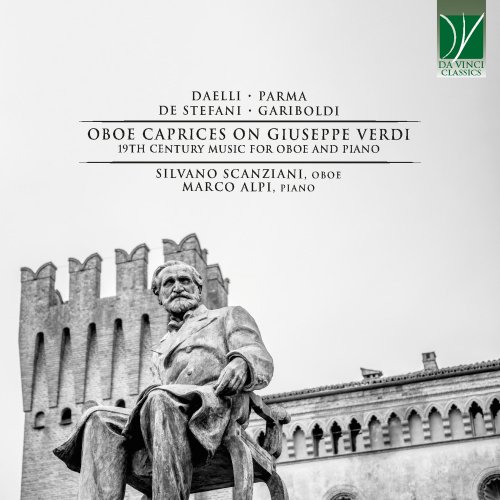

Silvano Scanziani & Marco Alpi - Daelli, Parma, De Stefani, Gariboldi: Oboe Caprices on Giuseppe Verdi (19th Century Music for Oboe and Piano) (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Silvano Scanziani, Marco Alpi

- Title: Daelli, Parma, De Stefani, Gariboldi: Oboe Caprices on Giuseppe Verdi (19th Century Music for Oboe and Piano)

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 51:12

- Total Size: 190 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

1. Fantasia sul "Rigoletto" in F Major (10:25)

2. Rimembranze dell'Opera "Un Ballo in Maschera" (08:37)

3. Divertimento sopra motivi dell'Opera "Attila" (05:53)

4. Fantasia sopra motivi dell'Opera "Il Trovatore" (07:12)

5. Divertimento sopra motivi dell'Opera "I Lombardi" (08:06)

6. Mosaico sopra "La Traviata" (10:57)

1. Fantasia sul "Rigoletto" in F Major (10:25)

2. Rimembranze dell'Opera "Un Ballo in Maschera" (08:37)

3. Divertimento sopra motivi dell'Opera "Attila" (05:53)

4. Fantasia sopra motivi dell'Opera "Il Trovatore" (07:12)

5. Divertimento sopra motivi dell'Opera "I Lombardi" (08:06)

6. Mosaico sopra "La Traviata" (10:57)

Many Italian musicians from the nineteenth century used to complain about the crisis of instrumental music in their country. After the splendid flourishing of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in the nineteenth century it seemed as if all creative energies of Italian music had been absorbed by operatic music. Various reasons have been adduced for this phenomenon.

In the nineteenth century, Italy was struggling for her independence. A series of wars, with abundant bloodshed, led eventually to the country’s (partial) unification in 1861. The movement leading to this political goal was called “Risorgimento” (meaning something akin to “resurrection” or “arising”), and it included secret societies, hidden plots, as well as organized guerrilla and official wars. Spirits were high, and – as some scholars have argued – the magniloquent expressivity of operatic music, its lyrics – at times very inflammatory and very relevant to the current political situation – and its tunes which could be sung in the roads, in the markets, and in the squares, all this concurred to the affirmation of opera as the main genre of Italian music. Moreover, the “public” dimension of opera seemed better suited to the need for sociality felt by many patriots. And, last but not least, opera was sung in Italian; also for this reason, it was considered as an “Italian” phenomenon. At a time when the country needed to become a country in the official sense, and to be recognized in her political and national identity, this quintessentially Italian genre was particularly cherished. By way of contrast, chamber music was both more neutral (being unprovided with lyrics which could identify a language and its people) and more “foreign”, since the great flourishing of chamber music came from Northern, and in particular from German-speaking countries. And since the archenemy, for many Italian patriots, was precisely the Austro-Hungarian Empire, it was understandable that Austrian composers or genres were not particularly favored in the Italian Risorgimento.

Yet, not all Italians were gifted with melodious voices, and singing was not for all. Many still loved to play instrumental music, and, in particular, the tradition of wind bands was very cherished – especially, but not exclusively, in rural contexts. The particular climatic situation of Italy, allowing for long months spent in open air, promoted and fostered the practice of wind bands, which in turn encouraged sociality, togetherness, and the expression of shared feelings through music.

Thus, a significant number of Italians could play wind instruments; and whilst their main performing outlet was the collective music-making of wind bands, they could play solo or chamber music works at home, with a few friends, and/or with the piano accompaniment which could be provided by their wives and daughters. (Winds were mostly played by men, whilst the piano was a primarily female instrument).

Although the level of these amateur musicians was not, generally speaking, that of a virtuoso, they still liked to try their hands with challenging pieces, preferably grounded on that same operatic tradition which was taking Italy by storm at the time. And when opera paraphrases or fantasies were actually too difficult for them to play, they could still admire, appreciate, and revere, those real virtuosos who could play them.

This is the cultural and social background for this Da Vinci Classics album, offering six works, with various titles, dedicated to Verdi’s operas and written for the oboe. Verdi, of course, epitomized the Italian Risorgimento culture as perhaps nobody else; it is well known that, when anti-Austrian propaganda was forbidden, many patriots wrote “W VERDI” on the walls, meaning not just an appreciation for the musician, but also their support for an alternative rule. VERDI was in fact an acronym for “Vittorio Emanuele Re D’Italia”, alluding to the King of Savoy and Sardinia who was leading the aspirations of the Italian patriots.

The works recorded here offer to the oboist the possibility of displaying the full palette of his or her virtuosity and expressiveness, while collating musical ideas excerpted from many different parts of the chosen opera. These works, lasting from five to ten minutes each, represent thus a miniature summary of the opera’s most beloved themes, woven together in a “rimembranza” (“remembrance”) or in a “mosaico” (a mosaic). Just as memory is made of scraps of facts woven together, so do these mosaics combine tiles from the opera they represent.

Of the composers represented here, at times very little is known, at times slightly more. For instance, we know about Raffaele Parma that he was born in Bologna in 1815 and died in the same city in 1883. He was a famous oboist at his time, performing in the orchestra of the Accademia Filarmonica (one of Italy’s most important musical institutions), and teaching at the Liceo Musicale (one of the most important Italian conservatories). His education had taken place under the guidance of another famous musician, Baldassarre Centoni, and his own published works, printed by Ricordi (Verdi’s own publisher) all focus on the operas of his famous Emilian colleague.

We know more about Giovanni Daelli, although, in several cases, the information we possess is undermined by the fact that both Giovanni and his younger brother Paolo Emilio were famous oboists. So, when just the family name is cited, we are always left wondering whether a biographical element refers to the one or to the other. Giovanni Daelli was a fellow student of Carlo Yvon (and not his pupil, as has been occasionally written) at the Conservatory of Milan. He was born around 1800, to a family which could have been artistically-minded, since there are artists with his same surname. Giovanni was admitted at the Conservatory of Milan in 1814, and graduated in 1820. The following year, Paolo Emilio entered the Conservatory in turn, and graduated in 1826 with honors. Two years later, the two brothers performed in Novara, on the occasion of a religious festival honoring the Virgin Mary; they played works by Pietro Generali (1773-1832), and were singled out by the reviewer for their exceptional musicianship. In the same year, one of the two Daellis was publicly praised for his performance on the occasion of a performance of Rossini’s Matilde di Shabran at the Teatro Re of Milan. Again in 1828, Daelli was appreciated not only as a player, but also as a composer of an Adagio with Variations. As the reviewer states, “The instrumental piece was an adagio and variations composed and performed on his instrument by the well-known professor of oboe, signor Daelli. The composition pleased; the performance could not be entirely effective due to an invincible fortuitous opening of a crack in the oboe. The public, however, persuaded by many earlier proofs of the real merit of the young Daelli, did not fail, then, to encourage him with the usual extremely fervid applause, nor to share with him the honor of being recalled to stage”. Both brothers performed extensively in operatic theatres, frequently taking part in the premieres of the important Risorgimento operas. Paolo Emilio remained in Milan until 1840, and then left for Barcelona, where he possibly died in about 1844. Giovanni did not leave his country, and performed at La Scala until a few days before his death, in 1860, at the eve of Italy’s unification. Since 1842, he had also taught at the Conservatory, where he acted as a librarian in 1852 and 1854. His compositional output focuses mainly on the oboe, but includes pieces for flute, clarinet, and bassoon.

Giuseppe Gariboldi belonged in the following generation. He had studied with Giuseppe D’Aloe, and then sought fortune in Paris, where he performed and composed. He also concertized in many European countries, including Belgium, the Netherlands, the UK and Austria, but found also time for serving as a Red Cross volunteer during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870. In the following year, he began teaching flute and composition in Paris, at the Collège Rollen; eventually, he moved back to Italy, in 1905. He wrote several etudes and concert pieces for flute and piano; his pedagogical works still attract the attention of teachers and students alike. His compositional output also includes songs and three operettas (Au Claire de Lune, La Jeunesse de Hoche, Le Rêve d’un écolier).

A contemporary of Gariboldi, Ricordàno De Stefani was born and died in Parma, Verdi’s city. He studied as a boarding pupil at the Royal Music School in his hometown, studying the oboe with Luigi Beccali and harmony with Giovanni Rossi. His Divertimento on Verdi’s Lombardi bears a dedication to “the famous Prof. Giacomo Mori”, paying homage to another famous oboist, who had passed away in the year of Italy’s unification. This allows us to establish inferentially that his work dates from approximately that period. The coeval success of this paraphrase is testified by its frequent performance during the intervals between the acts of operatic performances at the Royal Theatre of Parma (Teatro Regio), where De Stefani himself was a professional performer. His activity as an orchestra musician had begun, in fact, very early, when the musician was barely fourteen and had to seek permission from the Conservatory’s authorities, who were not in favor of a student going out at evenings for playing in an operatic theatre. Two years later, however, he was appointed an oboe player in the orchestra, and, in the following years, he was engaged by other institutions in the nearby region of the Marche (in Matelica and in Pesaro). His teaching activity included an appointment in Ferrara, but later led him to the Royal Music School of his hometown, where he had also studied. His output includes treatises and methods, etudes, along with paraphrases and fantasies for the oboe, but also works for solo piano.

Together, these composers bear witness to a lively musical culture, where opera certainly ruled, but where it also prompted and fostered the inspiration of instrumental works, bearing the distinctive mark of their composers’ personality.

In the nineteenth century, Italy was struggling for her independence. A series of wars, with abundant bloodshed, led eventually to the country’s (partial) unification in 1861. The movement leading to this political goal was called “Risorgimento” (meaning something akin to “resurrection” or “arising”), and it included secret societies, hidden plots, as well as organized guerrilla and official wars. Spirits were high, and – as some scholars have argued – the magniloquent expressivity of operatic music, its lyrics – at times very inflammatory and very relevant to the current political situation – and its tunes which could be sung in the roads, in the markets, and in the squares, all this concurred to the affirmation of opera as the main genre of Italian music. Moreover, the “public” dimension of opera seemed better suited to the need for sociality felt by many patriots. And, last but not least, opera was sung in Italian; also for this reason, it was considered as an “Italian” phenomenon. At a time when the country needed to become a country in the official sense, and to be recognized in her political and national identity, this quintessentially Italian genre was particularly cherished. By way of contrast, chamber music was both more neutral (being unprovided with lyrics which could identify a language and its people) and more “foreign”, since the great flourishing of chamber music came from Northern, and in particular from German-speaking countries. And since the archenemy, for many Italian patriots, was precisely the Austro-Hungarian Empire, it was understandable that Austrian composers or genres were not particularly favored in the Italian Risorgimento.

Yet, not all Italians were gifted with melodious voices, and singing was not for all. Many still loved to play instrumental music, and, in particular, the tradition of wind bands was very cherished – especially, but not exclusively, in rural contexts. The particular climatic situation of Italy, allowing for long months spent in open air, promoted and fostered the practice of wind bands, which in turn encouraged sociality, togetherness, and the expression of shared feelings through music.

Thus, a significant number of Italians could play wind instruments; and whilst their main performing outlet was the collective music-making of wind bands, they could play solo or chamber music works at home, with a few friends, and/or with the piano accompaniment which could be provided by their wives and daughters. (Winds were mostly played by men, whilst the piano was a primarily female instrument).

Although the level of these amateur musicians was not, generally speaking, that of a virtuoso, they still liked to try their hands with challenging pieces, preferably grounded on that same operatic tradition which was taking Italy by storm at the time. And when opera paraphrases or fantasies were actually too difficult for them to play, they could still admire, appreciate, and revere, those real virtuosos who could play them.

This is the cultural and social background for this Da Vinci Classics album, offering six works, with various titles, dedicated to Verdi’s operas and written for the oboe. Verdi, of course, epitomized the Italian Risorgimento culture as perhaps nobody else; it is well known that, when anti-Austrian propaganda was forbidden, many patriots wrote “W VERDI” on the walls, meaning not just an appreciation for the musician, but also their support for an alternative rule. VERDI was in fact an acronym for “Vittorio Emanuele Re D’Italia”, alluding to the King of Savoy and Sardinia who was leading the aspirations of the Italian patriots.

The works recorded here offer to the oboist the possibility of displaying the full palette of his or her virtuosity and expressiveness, while collating musical ideas excerpted from many different parts of the chosen opera. These works, lasting from five to ten minutes each, represent thus a miniature summary of the opera’s most beloved themes, woven together in a “rimembranza” (“remembrance”) or in a “mosaico” (a mosaic). Just as memory is made of scraps of facts woven together, so do these mosaics combine tiles from the opera they represent.

Of the composers represented here, at times very little is known, at times slightly more. For instance, we know about Raffaele Parma that he was born in Bologna in 1815 and died in the same city in 1883. He was a famous oboist at his time, performing in the orchestra of the Accademia Filarmonica (one of Italy’s most important musical institutions), and teaching at the Liceo Musicale (one of the most important Italian conservatories). His education had taken place under the guidance of another famous musician, Baldassarre Centoni, and his own published works, printed by Ricordi (Verdi’s own publisher) all focus on the operas of his famous Emilian colleague.

We know more about Giovanni Daelli, although, in several cases, the information we possess is undermined by the fact that both Giovanni and his younger brother Paolo Emilio were famous oboists. So, when just the family name is cited, we are always left wondering whether a biographical element refers to the one or to the other. Giovanni Daelli was a fellow student of Carlo Yvon (and not his pupil, as has been occasionally written) at the Conservatory of Milan. He was born around 1800, to a family which could have been artistically-minded, since there are artists with his same surname. Giovanni was admitted at the Conservatory of Milan in 1814, and graduated in 1820. The following year, Paolo Emilio entered the Conservatory in turn, and graduated in 1826 with honors. Two years later, the two brothers performed in Novara, on the occasion of a religious festival honoring the Virgin Mary; they played works by Pietro Generali (1773-1832), and were singled out by the reviewer for their exceptional musicianship. In the same year, one of the two Daellis was publicly praised for his performance on the occasion of a performance of Rossini’s Matilde di Shabran at the Teatro Re of Milan. Again in 1828, Daelli was appreciated not only as a player, but also as a composer of an Adagio with Variations. As the reviewer states, “The instrumental piece was an adagio and variations composed and performed on his instrument by the well-known professor of oboe, signor Daelli. The composition pleased; the performance could not be entirely effective due to an invincible fortuitous opening of a crack in the oboe. The public, however, persuaded by many earlier proofs of the real merit of the young Daelli, did not fail, then, to encourage him with the usual extremely fervid applause, nor to share with him the honor of being recalled to stage”. Both brothers performed extensively in operatic theatres, frequently taking part in the premieres of the important Risorgimento operas. Paolo Emilio remained in Milan until 1840, and then left for Barcelona, where he possibly died in about 1844. Giovanni did not leave his country, and performed at La Scala until a few days before his death, in 1860, at the eve of Italy’s unification. Since 1842, he had also taught at the Conservatory, where he acted as a librarian in 1852 and 1854. His compositional output focuses mainly on the oboe, but includes pieces for flute, clarinet, and bassoon.

Giuseppe Gariboldi belonged in the following generation. He had studied with Giuseppe D’Aloe, and then sought fortune in Paris, where he performed and composed. He also concertized in many European countries, including Belgium, the Netherlands, the UK and Austria, but found also time for serving as a Red Cross volunteer during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870. In the following year, he began teaching flute and composition in Paris, at the Collège Rollen; eventually, he moved back to Italy, in 1905. He wrote several etudes and concert pieces for flute and piano; his pedagogical works still attract the attention of teachers and students alike. His compositional output also includes songs and three operettas (Au Claire de Lune, La Jeunesse de Hoche, Le Rêve d’un écolier).

A contemporary of Gariboldi, Ricordàno De Stefani was born and died in Parma, Verdi’s city. He studied as a boarding pupil at the Royal Music School in his hometown, studying the oboe with Luigi Beccali and harmony with Giovanni Rossi. His Divertimento on Verdi’s Lombardi bears a dedication to “the famous Prof. Giacomo Mori”, paying homage to another famous oboist, who had passed away in the year of Italy’s unification. This allows us to establish inferentially that his work dates from approximately that period. The coeval success of this paraphrase is testified by its frequent performance during the intervals between the acts of operatic performances at the Royal Theatre of Parma (Teatro Regio), where De Stefani himself was a professional performer. His activity as an orchestra musician had begun, in fact, very early, when the musician was barely fourteen and had to seek permission from the Conservatory’s authorities, who were not in favor of a student going out at evenings for playing in an operatic theatre. Two years later, however, he was appointed an oboe player in the orchestra, and, in the following years, he was engaged by other institutions in the nearby region of the Marche (in Matelica and in Pesaro). His teaching activity included an appointment in Ferrara, but later led him to the Royal Music School of his hometown, where he had also studied. His output includes treatises and methods, etudes, along with paraphrases and fantasies for the oboe, but also works for solo piano.

Together, these composers bear witness to a lively musical culture, where opera certainly ruled, but where it also prompted and fostered the inspiration of instrumental works, bearing the distinctive mark of their composers’ personality.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

Facebook

Twitter

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads