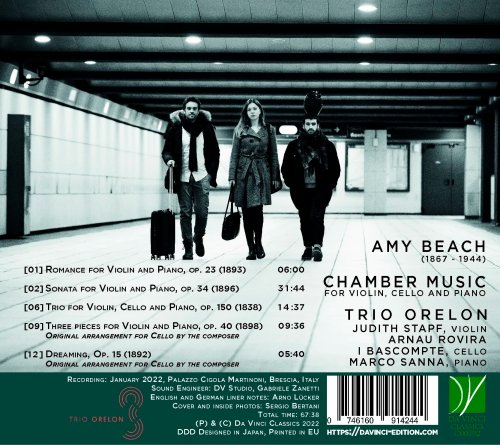

Trio Orelon - Amy Beach: Chamber Music for Violin, Cello and Piano (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Trio Orelon

- Title: Amy Beach: Chamber Music for Violin, Cello and Piano

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:08:12

- Total Size: 265 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Romance for Violin and Piano in A Major, Op. 23

02. Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Minor, Op. 34: I. Allegro moderato

03. Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Minor, Op. 34: II. Scherzo, molto vivace-più lento

04. Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Minor, Op. 34: III. Largo con dolore

05. Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Minor, Op. 34: IV. Allegro con fuoco

06. Trio in A Minor, Op. 150: I. Allegro (For Violin, Cello and Piano)

07. Trio in A Minor, Op. 150: II. Lento Espressivo-Presto (For Violin, Cello and Piano)

08. Trio in A Minor, Op. 150: III. Allegro con brio (For Violin, Cello and Piano)

09. Three pieces for Violin and Piano, Op. 40: No. 1, La captive (Arrangement for Cello by the Composer)

10. Three pieces for Violin and Piano, Op. 40: No. 2, Berceuse (Arrangement for Cello by the Composer)

11. Three pieces for Violin and Piano, Op. 40: No. 3, Mazurka (Arrangement for Cello by the Composer)

12. Dreaming, Op. 15 (Arrangement for Cello by the Composer from Four Sketches)

Sometimes you don’t even know how to start. And sometimes you don’t even know what to do with your desperation! Who would deny the fact that female composers wrote great music? But besides that, who would deny that many old white men in the music industry still believe their own sexism, their own fear of some sort of exposure or overturning of their convoluted “concepts of masculinity” by actually claiming that women have always composed “worse” than men? Fact is: women compose better; simply because they had to endure far greater struggles in the past in order to be allowed to become composers at all. Because those who faced struggles and adversities as well as ongoing problems are also more involved in their respective art, they experience a completely different kind of existentialist epiphany and were therefore composing and making music to a certain extent for their lives. You don’t fight your way through for nothing!

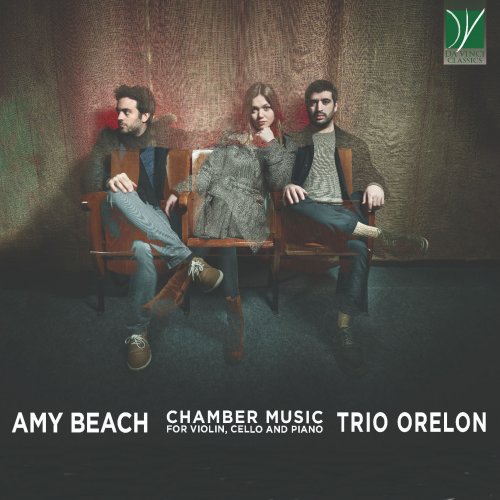

On this album, a trio of three young people – one woman, two men – plays works by a woman. In fact, there shouldn’t be anything unusual about that. But also the intense preoccupation of the Trio Orelon here with the works of Amy Beach means: existential devotion. Complete devotion to five works by a woman who does not need to be rehabilitated, excused – nor “explained”. Because at some point the whole world will know (and therefore not have to talk about it anymore): Amy Beach was a fantastic composer. Let’s get to know her!

She was born named Amy Marcy Cheney on the 5th September 1867- probably a tranquil, late-summer day. Perhaps it was one of those days when tourists swarmed with hopes of the “Indian Summer”. Amy’s place of birth was the small town of Henniker in the educated, prosperous and well-protected US state of New Hampshire – which was in the late summer always gifted with nature’s colorful impressions. Although Henniker is- to be honest- a village, the town hall of the New England College there regularly hosted events for prospective US presidential candidates as a venue for their election campaign. So this place Henniker can’t be that insignificant!

Amy’s mother Clara was considered an excellent pianist and singer – and apparently inspired her daughter with her love of music from very early on. Apparently Amy’s constant fiery devotion to music flared up so much (“too much”) that her mother Clara became afraid – and at times even forbade Amy to take piano lessons! In general, Amy’s parents were very critical of their daughter’s musical career. Unfortunately, that was still typical for the time, but – let’s see the “good” in it – Amy was, unlike poor Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, not “sold” by her parents as a “child prodigy” on the music market. A concept that, as we know today from numerous tragic examples, leads very often to nothing, yes, and sometimes even to ruin.

But such musical talent often easily breaks open the providential layer of parental wishes and visions, like a plant’s tendril first breaking up out the ground and then spreading at will. Amy, at least, was said to be able to sing songs with astonishing precision of intonation at one year of age. And by the age of two, she was said to be able to add counterpoint to a given voice while singing. At the age of three she was able to read perfectly – which is the completely “normal” goal of many helicopter parents these days. And, more importantly, at the age of four, Amy produced a series of little piano waltzes- her first own compositions!

In 1875, Amy’s family moved to a suburb of Boston. There she received piano lessons from the Liszt student Carl Baermann (1811–1885), who actually became a legendary clarinetist; at the age of 14 she took her first (and only!) composition lessons in harmony and counterpoint from the now completely unknown Junius W. Hill (1840-1916); it is said that Beach acquired her other skills in the fields of composition and music theory entirely autodidactically.

At the age of 16, Amy was enthusiastically celebrated as a pianist in the Boston Music Hall. In October 1883 she had successfully performed there- playing works by Chopin and Moscheles under the direction of Adolph Neuendorff (1843-1897), who had conducted the very first performance of Wagner’s Lohengrin in the USA in 1871. Two years later, in 1885, at the age of 18, Amy married the then 42-year-old physician Henry Harris Aubrey Beach (1843-1910) – and took his surname. The marriage contract between the two, which was not uncommon at the time, provided for Amy Beach’s total subordination, although the (childless) marriage was repeatedly described in the literature as “happy”; Amy Beach agreed to actively teach piano during the marriage and limit her concert career as a pianist to one or two performances a year. In addition, she was required to donate her concert fees to charity and was also forbidden from further studying musical subjects. (One could become angry if one did not know how “normal” such oppressive madness was at the time).

However, these impossible regulations and restrictions allowed for an even more extensive occupation with composing! In 1892 the Four Sketches op. 15 were composed; intended originally for solo piano, Beach arranged the pieces into a version for cello and piano. The wonderful, romantic piece Dreaming, which Arnau Rovira i Bascompte and Marco Sanna play on this album, may at first be reminiscent of Franz Schubert’s G flat major Impromptu D 899 from 1827. But Amy Beach quickly abandons that all too pleasing epigone territory by harmoniously illuminating and evolving the material based on (supposedly) Schubertian ideas.

Similarly wonderfully amorous and full of love and warmth is Beach’s Romance for violin and piano op. 23, which was composed a year later in 1893. Like the love motive of a friendly Richard Wagner, an E major line evolves in the piano in a sonorous baritone register. A line with excellent suitability for imitative continuation intertwined with reservation, wistful and longing. Yes, the piano tells a short, bittersweet love story in four bars, even before the violin is allowed to present it’s own point of view. With a sigh of relief almost, the violin presents a similar outlook on the possibly erotic unity – and allows us to be carried away on a soft bed in A major.

On October 30th in 1896, Beach’s Gaelic Symphony was premiered. None of the reviewers at the time omitted to point out that this composition was the “work of a woman”, ignoring the fact that one of America’s most important orchestras, namely the Boston Symphony Orchestra itself, was responsible for the premiere… In the same year, Beach composed her Sonata for Violin and Piano, Op. 34. This sonata begins like a deadly serious Brahms ballad and the piano promptly hands over to the violin. But Beach’s music proves to be sweeter and more vocal than “Brahms’ model”. The serious, bearded Brahms would not have allowed himself such a beautiful, bell-like shift in register as we are allowed to enjoy after a few moments.

Two years later (1898) Beach presented the three programmatic Pieces for violin and piano op. 40. We hear them on this album in a version for cello and piano. The title of the first piece – La Captive (The Captive) – is intended to be deadly serious on the one hand, and slightly ironic on the other. The “imprisonment” suggests a similar musical setting as to the one used by François Couperin in his harpsichord piece, still nowadays not yet correctly deciphered, Les Barricades mystérieuses in 1717. It is less about the pity that we take on a real prisoner, but about the deliberately limited tonal space of an instrument. In Beach’s Opus 40, it is – alongside decadently “masculine” freedom in the piano, which plays ballad-like and proud – the violin, which (according to Amy Beach’s instructions) is required to play exclusively on the lowest string. A decision with corresponding consequences for the sound and expressive content of the whole piece.

In 1910 Amy Beach’s husband died – and she resumed her concert activities. Until the beginning of World War I, she went on highly successful tours through Europe, during which she always, as a pianist, was able to include her own compositions on the program. Soon, Beach expressed herself publicly against the everyday and intellectual discrimination of women and promoted the benefits of extensive education for all people, regardless of gender, marriage, or motherhood. In 1926 she became co-founder and president of the Association of American Women Composers – and today she is rightfully seen as a pioneer of the women’s movement in the United States.

In 1932, she wrote her only opera, Cabildo, which was however not premiered until two or three years after her death. In Europe, however, this musical theatre piece has never once been heard on a major stage. Six years later – in the dark year of 1938 – Amy Beach’s Trio for violin, violoncello and piano op. 150 appeared on the horizon; a work that more and more ensembles are taking into their repertoire.

We hear an aesthetically distinctly transformed, progressive, informed Amy Beach. The piano circles us emotionally ambiguously with 32nd-notes and on top of this rises a very simple line in the cello. One is reminded of chilled impressionism à la Ravel or Debussy. The cello briefly breathes a sigh of relief in a quarter rest to continue formulating its restrained lament under an ever more iridescent and irritating piano hush. One is almost relieved when the Guarneri violin of Judith Stapf enters warmly, confidently and peacefully. But also from her side worried thoughts come into our heart. What an exciting mixture of full romanticism and impressionism! A music that never imposes itself unpleasantly, but which on the other hand never shies away from offense in a purely “aesthetical” way- quite on the contrary. Beach carries us away, lets long lines sing, often oscillating in wonderfully shimmering coloured harmonies – and never sounds contrived or too intentional. Her music arises “as if by itself”, but by no means belongs in the pleasing salon of the 19th century!

Beach herself once said about her composing: “It has happened more than once that a composition has come to me, ready-made as it were, between the demands of other works.”

After her extensive European guest appearances, Beach lived again in New Hampshire for several years. In the 1920s years, she lived in New York City, where she was, in a sense, composer in residence for many years, composing music for the St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church. A heart disease led to her retirement in 1940 and Amy Beach died on December 27, 1944, at the age of 77 in New York City as a result of her illness. She left behind music that never leaves us cold, never clumsily shocks us, but wants to take us by the hand of musical narration. Music of the greatest intensity, great cleverness – and dazzling brilliance. It’s time for Beach.

01. Romance for Violin and Piano in A Major, Op. 23

02. Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Minor, Op. 34: I. Allegro moderato

03. Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Minor, Op. 34: II. Scherzo, molto vivace-più lento

04. Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Minor, Op. 34: III. Largo con dolore

05. Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Minor, Op. 34: IV. Allegro con fuoco

06. Trio in A Minor, Op. 150: I. Allegro (For Violin, Cello and Piano)

07. Trio in A Minor, Op. 150: II. Lento Espressivo-Presto (For Violin, Cello and Piano)

08. Trio in A Minor, Op. 150: III. Allegro con brio (For Violin, Cello and Piano)

09. Three pieces for Violin and Piano, Op. 40: No. 1, La captive (Arrangement for Cello by the Composer)

10. Three pieces for Violin and Piano, Op. 40: No. 2, Berceuse (Arrangement for Cello by the Composer)

11. Three pieces for Violin and Piano, Op. 40: No. 3, Mazurka (Arrangement for Cello by the Composer)

12. Dreaming, Op. 15 (Arrangement for Cello by the Composer from Four Sketches)

Sometimes you don’t even know how to start. And sometimes you don’t even know what to do with your desperation! Who would deny the fact that female composers wrote great music? But besides that, who would deny that many old white men in the music industry still believe their own sexism, their own fear of some sort of exposure or overturning of their convoluted “concepts of masculinity” by actually claiming that women have always composed “worse” than men? Fact is: women compose better; simply because they had to endure far greater struggles in the past in order to be allowed to become composers at all. Because those who faced struggles and adversities as well as ongoing problems are also more involved in their respective art, they experience a completely different kind of existentialist epiphany and were therefore composing and making music to a certain extent for their lives. You don’t fight your way through for nothing!

On this album, a trio of three young people – one woman, two men – plays works by a woman. In fact, there shouldn’t be anything unusual about that. But also the intense preoccupation of the Trio Orelon here with the works of Amy Beach means: existential devotion. Complete devotion to five works by a woman who does not need to be rehabilitated, excused – nor “explained”. Because at some point the whole world will know (and therefore not have to talk about it anymore): Amy Beach was a fantastic composer. Let’s get to know her!

She was born named Amy Marcy Cheney on the 5th September 1867- probably a tranquil, late-summer day. Perhaps it was one of those days when tourists swarmed with hopes of the “Indian Summer”. Amy’s place of birth was the small town of Henniker in the educated, prosperous and well-protected US state of New Hampshire – which was in the late summer always gifted with nature’s colorful impressions. Although Henniker is- to be honest- a village, the town hall of the New England College there regularly hosted events for prospective US presidential candidates as a venue for their election campaign. So this place Henniker can’t be that insignificant!

Amy’s mother Clara was considered an excellent pianist and singer – and apparently inspired her daughter with her love of music from very early on. Apparently Amy’s constant fiery devotion to music flared up so much (“too much”) that her mother Clara became afraid – and at times even forbade Amy to take piano lessons! In general, Amy’s parents were very critical of their daughter’s musical career. Unfortunately, that was still typical for the time, but – let’s see the “good” in it – Amy was, unlike poor Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, not “sold” by her parents as a “child prodigy” on the music market. A concept that, as we know today from numerous tragic examples, leads very often to nothing, yes, and sometimes even to ruin.

But such musical talent often easily breaks open the providential layer of parental wishes and visions, like a plant’s tendril first breaking up out the ground and then spreading at will. Amy, at least, was said to be able to sing songs with astonishing precision of intonation at one year of age. And by the age of two, she was said to be able to add counterpoint to a given voice while singing. At the age of three she was able to read perfectly – which is the completely “normal” goal of many helicopter parents these days. And, more importantly, at the age of four, Amy produced a series of little piano waltzes- her first own compositions!

In 1875, Amy’s family moved to a suburb of Boston. There she received piano lessons from the Liszt student Carl Baermann (1811–1885), who actually became a legendary clarinetist; at the age of 14 she took her first (and only!) composition lessons in harmony and counterpoint from the now completely unknown Junius W. Hill (1840-1916); it is said that Beach acquired her other skills in the fields of composition and music theory entirely autodidactically.

At the age of 16, Amy was enthusiastically celebrated as a pianist in the Boston Music Hall. In October 1883 she had successfully performed there- playing works by Chopin and Moscheles under the direction of Adolph Neuendorff (1843-1897), who had conducted the very first performance of Wagner’s Lohengrin in the USA in 1871. Two years later, in 1885, at the age of 18, Amy married the then 42-year-old physician Henry Harris Aubrey Beach (1843-1910) – and took his surname. The marriage contract between the two, which was not uncommon at the time, provided for Amy Beach’s total subordination, although the (childless) marriage was repeatedly described in the literature as “happy”; Amy Beach agreed to actively teach piano during the marriage and limit her concert career as a pianist to one or two performances a year. In addition, she was required to donate her concert fees to charity and was also forbidden from further studying musical subjects. (One could become angry if one did not know how “normal” such oppressive madness was at the time).

However, these impossible regulations and restrictions allowed for an even more extensive occupation with composing! In 1892 the Four Sketches op. 15 were composed; intended originally for solo piano, Beach arranged the pieces into a version for cello and piano. The wonderful, romantic piece Dreaming, which Arnau Rovira i Bascompte and Marco Sanna play on this album, may at first be reminiscent of Franz Schubert’s G flat major Impromptu D 899 from 1827. But Amy Beach quickly abandons that all too pleasing epigone territory by harmoniously illuminating and evolving the material based on (supposedly) Schubertian ideas.

Similarly wonderfully amorous and full of love and warmth is Beach’s Romance for violin and piano op. 23, which was composed a year later in 1893. Like the love motive of a friendly Richard Wagner, an E major line evolves in the piano in a sonorous baritone register. A line with excellent suitability for imitative continuation intertwined with reservation, wistful and longing. Yes, the piano tells a short, bittersweet love story in four bars, even before the violin is allowed to present it’s own point of view. With a sigh of relief almost, the violin presents a similar outlook on the possibly erotic unity – and allows us to be carried away on a soft bed in A major.

On October 30th in 1896, Beach’s Gaelic Symphony was premiered. None of the reviewers at the time omitted to point out that this composition was the “work of a woman”, ignoring the fact that one of America’s most important orchestras, namely the Boston Symphony Orchestra itself, was responsible for the premiere… In the same year, Beach composed her Sonata for Violin and Piano, Op. 34. This sonata begins like a deadly serious Brahms ballad and the piano promptly hands over to the violin. But Beach’s music proves to be sweeter and more vocal than “Brahms’ model”. The serious, bearded Brahms would not have allowed himself such a beautiful, bell-like shift in register as we are allowed to enjoy after a few moments.

Two years later (1898) Beach presented the three programmatic Pieces for violin and piano op. 40. We hear them on this album in a version for cello and piano. The title of the first piece – La Captive (The Captive) – is intended to be deadly serious on the one hand, and slightly ironic on the other. The “imprisonment” suggests a similar musical setting as to the one used by François Couperin in his harpsichord piece, still nowadays not yet correctly deciphered, Les Barricades mystérieuses in 1717. It is less about the pity that we take on a real prisoner, but about the deliberately limited tonal space of an instrument. In Beach’s Opus 40, it is – alongside decadently “masculine” freedom in the piano, which plays ballad-like and proud – the violin, which (according to Amy Beach’s instructions) is required to play exclusively on the lowest string. A decision with corresponding consequences for the sound and expressive content of the whole piece.

In 1910 Amy Beach’s husband died – and she resumed her concert activities. Until the beginning of World War I, she went on highly successful tours through Europe, during which she always, as a pianist, was able to include her own compositions on the program. Soon, Beach expressed herself publicly against the everyday and intellectual discrimination of women and promoted the benefits of extensive education for all people, regardless of gender, marriage, or motherhood. In 1926 she became co-founder and president of the Association of American Women Composers – and today she is rightfully seen as a pioneer of the women’s movement in the United States.

In 1932, she wrote her only opera, Cabildo, which was however not premiered until two or three years after her death. In Europe, however, this musical theatre piece has never once been heard on a major stage. Six years later – in the dark year of 1938 – Amy Beach’s Trio for violin, violoncello and piano op. 150 appeared on the horizon; a work that more and more ensembles are taking into their repertoire.

We hear an aesthetically distinctly transformed, progressive, informed Amy Beach. The piano circles us emotionally ambiguously with 32nd-notes and on top of this rises a very simple line in the cello. One is reminded of chilled impressionism à la Ravel or Debussy. The cello briefly breathes a sigh of relief in a quarter rest to continue formulating its restrained lament under an ever more iridescent and irritating piano hush. One is almost relieved when the Guarneri violin of Judith Stapf enters warmly, confidently and peacefully. But also from her side worried thoughts come into our heart. What an exciting mixture of full romanticism and impressionism! A music that never imposes itself unpleasantly, but which on the other hand never shies away from offense in a purely “aesthetical” way- quite on the contrary. Beach carries us away, lets long lines sing, often oscillating in wonderfully shimmering coloured harmonies – and never sounds contrived or too intentional. Her music arises “as if by itself”, but by no means belongs in the pleasing salon of the 19th century!

Beach herself once said about her composing: “It has happened more than once that a composition has come to me, ready-made as it were, between the demands of other works.”

After her extensive European guest appearances, Beach lived again in New Hampshire for several years. In the 1920s years, she lived in New York City, where she was, in a sense, composer in residence for many years, composing music for the St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church. A heart disease led to her retirement in 1940 and Amy Beach died on December 27, 1944, at the age of 77 in New York City as a result of her illness. She left behind music that never leaves us cold, never clumsily shocks us, but wants to take us by the hand of musical narration. Music of the greatest intensity, great cleverness – and dazzling brilliance. It’s time for Beach.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads