Tracklist:

1. Waltz (02:47)

2. Five improvisations, Op. 148: I. Lento molto tranquillo (02:37)

3. Five improvisations, Op. 148: II. Allegretto grazioso e capriccioso (01:27)

4. Five improvisations, Op. 148: III. Allegro con delicatezza (01:20)

5. Five improvisations, Op. 148: IV. Molto lento e tranquillo (02:22)

6. Five improvisations, Op. 148: V. Largo maestoso (02:50)

7. Vestiges (03:28)

8. Night thoughts (Homage to Ives) (07:02)

9. Haiku: No. 1 (00:45)

10. Haiku: No. 1, Second Version (00:39)

11. Haiku: No. 2 (00:30)

12. Haiku: No. 3 (00:42)

13. Haiku: No. 4 (00:27)

14. Haiku: No. 5 (00:38)

15. Haiku: No. 6 (00:37)

16. Touches (Chorale, Eigth Variations And Coda) (08:14)

17. Palais de Mari (22:17)

18. Mad rush (14:48)

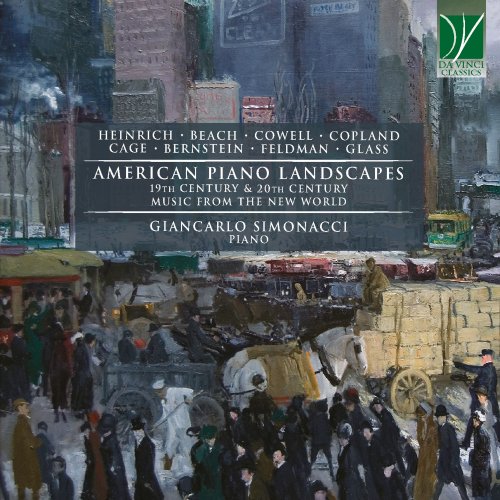

This Da Vinci Classics album not only offers a savoury experience of piano works written by some of the most important American composers, but also helps the listener to understand the links and connections among the featured composers. Non man (or woman) is an island, and this is especially true for musicians. Whilst great composers always have a more or less prominent element of originality, this is never entirely severed from a relationship with artists of the past and with living colleagues. This relationship, of course, may be of proximity or opposition; new ideas are born both from imitation and from rejection.

Our itinerary begins with a Waltz written by Anthony Philip Heinrich. He is considered as the first American composer, even though (as will happen with several other musicians represented in this album) he was not American born. But this is a feature shared by many great figures of American history and culture, and represents a landmark of the “American” lifestyle: a welcoming attitude, where immigrants and refugees can find their home and express their potential in a continuing dialogue with what America already is.

Heinrich was Bohemian born. In spite of the rich musical tradition of his native land, his first steps in life were not in the direction of professional musicianship. He had been trained to succeed his rich uncle in business, and this he did. Until, in 1810, the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars extinguished the large patrimony he had inherited; this misfortune found him in Boston. Seeking his way in life, he embarked on a 700-mile journey on foot and by boat. This pilgrimage brought him into the heart of early-nineteenth-century America, whose natural beauties and native culture fascinated him. He decided to become a professional composer and conductor, and to dedicate his skills and talents to the celebration of the American landscapes, nature, and original culture. He was among the first “classically-trained” composers who employed tunes and musical gestures excerpted from the musical heritage of the American Natives. His descriptive music is highly original and mirrors a Romantic view of America, characterized by passionate enthusiasm for its amazing panoramas.

Heinrich also brought the American culture he had discovered and embraced to Europe, conducting widely acclaimed concerts there; at the same time, he championed European music in his adoptive country, conducting the first-ever performance of a Beethoven Symphony on American ground.

Another “first-ever” characterizes the life of Amy Beach, whose Gaelic Symphony was the first work in this genre to have been written and published by an American woman. Amy Beach’s life, indeed, was exceptional from its very beginnings. She had been born to a very artistic and musical family, and displayed very unusual gifts from her earliest childhood: she could sing accurately many songs at age one, could improvise counterpoint at two, and taught herself to read very soon. Her mother gave her the first rudiments of musical performance, and prepared her for her debut, which took the audience by storm. She then began formal training with, among others, a former pupil of Franz Liszt, and made her debut with orchestra at sixteen, to great acclaim. After her marriage, she was requested by her husband to limit her performing activity to just two charity concerts per year, and she dedicated herself to composition. Even though she felt a pianist at heart, we can be grateful for this turn of events since this allowed her to produce a large and significant repertoire of genuinely “American” music. Different from many other American musicians of her time, indeed, Beach never studied in Europe (but studied very carefully the most important writings of European theoreticians).

Many of her works depict American landscapes, plants, flowers, occasions, and situations. After her husband’s death, and a period of intense suffering following it, she resumed playing and toured extensively both America and Europe. She became a leading figure of contemporaneous music, and devoted herself also to the musical education of the young (with particular attention to young female musicians).

Her Five Improvisations op. 148 mirror the depth of her reflection and the profundity of her spirituality. They are characterized by the use of a more modern language than that found in most of her other piano works.

Modernism was instead the most recognizable trait of Henry Cowell’s music, to the point that he was labelled an ultra-modernist. Different from Heinrich’s, Cowell’s life began in poverty. When his parents divorced, Cowell – who was still a child – earned a living for himself and for his mother through a number of poorly-paid jobs. His (and our) fortune was that his keen intelligence and immense talent were discovered by a Stanford University Professor, who obtained for him a scholarship at Stanford, enabling him to study English (his formal education had stopped at grade three!) and composition with Charles Seeger, who mentored him.

Cowell began experimenting with new means of sound production, including, most famously, “clusters” – i.e. the simultaneous emission of adjacent notes on the piano, produced by pressing the keys with the forearm. The outrage and scandal caused by some of his performances brought him international fame. Béla Bartók was so impressed by his techniques that he asked his American colleague for permission to use them in his own works. Cowell’s influence cannot be measured, and, in particular, was determining for the musical development of musicians such as John Cage. One of Cage’s most typical and famous creations, the prepared piano, derives rather directly from Cowell’s experiments. The piece recorded here, Vestiges, has much in common with the experiments of other contemporaneous composers, in particular with the European Expressionists. However, in this case, Cowell maintains a tonal context, while employing non-tonal harmonies freely. Cowell also founded a journal, called New Music Quarterly, which championed new music – among others by young composers such as Aaron Copland.

At first sight, Aaron Copland’s music seems much less modernist than Cowell’s, however. But this applies mainly to the works composed by Copland in what he labelled as his “vernacular” style: a direct, immediate, easily understandable style, which his detractors called “populist”. Such works were conceived as a reaction to the Great Depression, and brought some fresh air to the numerous Americans who sought beauty and inspiration in music. Born to a family of Jewish-Lithuanian immigrants, Copland found a twentieth-century language for depicting that same, gorgeous, American nature which had already fascinated Heinrich and Beach. His Night Thoughts were written as a compulsory piece for the sight-reading test at the Van Cliburn International Competition (1972). The work is dedicated to another major American composer, Charles Ives, but, allegedly, the dedication was added to the already-composed piece. Thus, if this corresponds to truth, the seemingly “Ivesian” traits of the piece’s opening (which may recall The Unanswered Questions) are unintentional.

We have already mentioned the importance of Cowell’s music for the compositional development of John Cage. Beyond Cowell’s experiments with the piano’s sonorities, Cowell also indirectly taught Cage to consider the non-Western musical traditions, and these were equally foundational for Cage’s own style. His Haikus are a notable example of this, but one might also mention Cage’s noteworthy use of the I-Ching as a compositional method. Works referring to the Japanese tradition of haiku poetry are comparatively numerous in Cage’s output. In fact, this is easily explained if one considers Cage’s fascination with numbers (and the Japanese haiku is built on 5-7-5 syllabic structures) and his interest in silence (and haiku poems are, in a manner of speaking, surrounded by silence).

Like Copland’s Night Thoughts, also Leonard Bernstein’s Touches had been commissioned by the Van Cliburn Competition. This set constituted by a Chorale, followed by eight Variations and a Coda, is also one of Bernstein’s last piano works; significantly, it is dedicated “to my first love, the keyboard”. The inspiration for this work came to Bernstein from a composition by Copland, his Piano Variations, which Bernstein had loved since his adolescence. The Chorale of Bernstein’s Touches is derived from an earlier composition he had written for his daughter Jamie.

If Cowell influenced Cage, Cage influenced Morton Feldman, who in turn came from a family of Russian- Jewish immigrants. And, like Bernstein’s Touches, also Feldman’s Palais de Mari is the composer’s last piano work. It is a transparent work, full of light and of delicacy, and reveals Feldman’s debt toward Cage in the fascination for silence.

Silence is also a fundamental element in Philip Glass’ poetics. Glass’ family, like Copland’s was a Jewish family from Lithuania. During his years as a music student in Paris, where he studied with Copland’s teacher Nadia Boulanger, his most intense musical experiences came from the works of two American – rather than French! – musicians, i.e. Cage and Feldman. The continuity among their musical idioms, in spite of the obvious differences, is revealed in Mad Rush. Notwithstanding its title, this piece has very little of either madness and rush, and was included into a studio album of 1989 recorded by Glass himself at the piano. Mad Rush, written in 1979, is the elaboration of an earlier work for the organ, and had been employed as the music for a ballet by choreographers Lucinda Childs and Benjamin Millepied.

Together, therefore, these works and their artists build a fascinating net of references, influences, reactions, and relationships, which reveal the full variety of the American musical vein and inspiration.