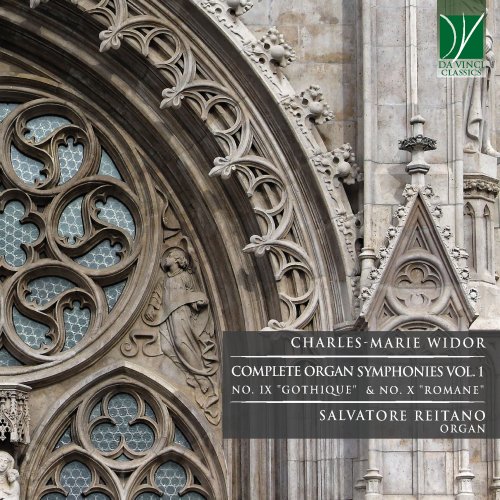

Salvatore Reitano - Charles-Marie Widor: Complete Organ Symphonies VOL. 1 - No. IX "Gothique" & No. X "Romane" (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Salvatore Reitano

- Title: Charles-Marie Widor: Complete Organ Symphonies VOL. 1 - No. IX "Gothique" & No. X "Romane"

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 1:15:55

- Total Size: 339 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

1. Symphonie Gothique in C Minor, Op. 70: I. Moderato (08:11)

2. Symphonie Gothique in C Minor, Op. 70: II. Andante (06:23)

3. Symphonie Gothique in C Minor, Op. 70: III. Allegro (05:17)

4. Symphonie Gothique in C Minor, Op. 70: IV. Moderato (16:23)

5. Symphonie Romane in D Major, Op. 73: I. Moderato (08:57)

6. Symphonie Romane in D Major, Op. 73: II. Choral (adagio) (11:22)

7. Symphonie Romane in D Major, Op. 73: III. Cantilène (Lento) (06:56)

8. Symphonie Romane in D Major, Op. 73: IV. Final (Allegro) (12:23)

1. Symphonie Gothique in C Minor, Op. 70: I. Moderato (08:11)

2. Symphonie Gothique in C Minor, Op. 70: II. Andante (06:23)

3. Symphonie Gothique in C Minor, Op. 70: III. Allegro (05:17)

4. Symphonie Gothique in C Minor, Op. 70: IV. Moderato (16:23)

5. Symphonie Romane in D Major, Op. 73: I. Moderato (08:57)

6. Symphonie Romane in D Major, Op. 73: II. Choral (adagio) (11:22)

7. Symphonie Romane in D Major, Op. 73: III. Cantilène (Lento) (06:56)

8. Symphonie Romane in D Major, Op. 73: IV. Final (Allegro) (12:23)

In the history of music, there are several significant examples of composers whose output is significantly dominated by works written for a specific instrument. The identification between Chopin and the piano, Paganini and the violin, or Tárrega and the guitar is almost total (even though at least the first two did not limit themselves to their favourite instrument). And this identification obviously depends on the composer’s own activity as a performer (as a great, virtuoso performer) on that same instrument. Less frequently, however, such an identification does not merely involve a composer and an instrument, but rather a particular brand of that instrument’s production. This is what happened with Charles-Marie Widor, the organ, and in particular the Cavaillé-Coll organs.

Of course, Chopin favoured Pleyel pianos, but his works do not depend so dramatically on Pleyel pianos as Widor’s on Cavaillé-Coll organs. This is due to a number of reasons. Firstly, the difference between a Cavaillé-Coll organ and another organ of the same or of the preceding eras is incomparably more pronounced than that between a Pleyel and an Érard piano of the mid-nineteenth century. The difference between an earlier organ and a Cavaillé-Coll is more akin to that between Beethoven’s and Bruckner’s orchestras. And this is precisely because the Cavaillé-Coll organs developed a symphonic concept of the organ. Thus, it is not merely a matter of quantity (even if this does matter, when an unprecedented number of pipes and keyboards is involved), and not even just a matter of quality, but rather an almost ontological difference. Earlier organs and Cavaillé-Coll organs are like to evolutionary stages in a species. Secondly, the very idea of a symphonic organ is strictly bound, in a reciprocal influence, to that of an organ symphony, the genre Widor virtually created and which remains most closely associated with his compositional output. Thirdly, Widor’s symphonies were conceived, imagined, realised, and performed on these organs, and Widor’s six-decades long acquaintance with the organ of St.-Sulpice was crucial for the development of his repertoire and style. Fourthly, and not less importantly, Widor would hardly have had the opportunities he had to experiment, try, and create on those instruments, had it not been for Aristide Cavaillé-Coll’s encouragement, support, and active promotion.

Widor, indeed, was practically born on the organ loft. His father was an esteemed organist from Lyons, and began teaching his son very early. Thus, different from many other organists who moved their first steps as pianists and then moved to the organ (or added organ playing to their activity as pianists: this happened, for instance, with Saint-Saëns), Widor was “born” an organist. Already at eleven he was his father’s assistant and occasionally replaced him in his duties. Cavaillé-Coll was a family friend, and was quick to notice Charles-Marie’s precocious talent and innate predisposition for organ playing. Thanks to his good offices and influence, at nineteen Widor was accepted as a student by two of the greatest Belgian musicians of the era. In Brussels, in fact, Charles-Marie studied under the guidance of legendary organist Jacques Lemmens (1823-1881), and of the even more legendary François-Joseph Fétis, who was already in his eighties at the time. Fétis had been a leading figure of the European musical world, and represented a repository of compositional techniques and knowledge. The young man was eager to learn from him, and doubtlessly acquired from both teachers the ability which later characterized him.

But Aristide Cavaillé-Coll had not forgotten his protégé, nor abandoned him in Belgium. As soon as Widor’s education was accomplished, Cavaillé-Coll introduced him to the most important milieus of French- and French-speaking culture; thus, the young musician befriended such musicians as Saint-Saëns, César Franck, Meyerbeer, and foreign musicians such as Liszt and Rossini who lived in Paris. Widor’s career proceeded quickly and securely. At just twenty-four, he inaugurated the new, magnificent Cavaillé-Coll organ in the Cathedral Church of Notre Dame, along with six other organists. The following year, he participated in the inauguration of another Cavaillé-Coll organ at La Trinité (that organ, in the following century, would become inextricably associated with Olivier Messiaen). And just a few months later, Cavaillé-Coll, Gounod and Saint-Saëns (of whom Widor by then had become the assistant) managed an almost incredible coup. Upon the retirement of Louis James Alfred Lefébure-Wély, who had been the titular organist at St.-Sulpice, Widor’s influential friends secured for him the possibility of a provisional, one-year appointment as an organist in that church. That provisional, one-year appointment would last for six decades!

What should be noted is that the St.-Sulpice organ was the greatest and most impressive organ ever built by Cavaillé-Coll; it was an exceptional instrument, a masterpiece of technology and musicianship, and a rather intimidating monster with its unequalled size and power. That organ had been built in 1862, and comprised more than 100 stops, nearly 7000 pipes, 20 windchests, and the list could go on. As Widor would later recall, his symphonies could not have existed without that organ: “It was when I felt the pipes of the Saint-Sulpice organ vibrating under my hands and feet that I took to writing my first four organ symphonies. I did not seek any particular style or form. I wrote feeling them deeply, asking myself if they were inspired by Bach or Mendelssohn. No! I was listening to the sonorousness of Saint-Sulpice, and naturally I sought to extract from it a musical fabric – trying to make pieces that, while being free, featured some contrapuntal procedures”.

Whilst earlier organs, in fact, were conceived first and foremost in order to bring out the clarity of the polyphonic texture, and to let it emerge, the Cavaillé-Coll organs aimed rather at evoking the full palette of a modern symphonic orchestra, in terms of timbral variety, of dynamic range, and of flexibility in the transition from one dynamic level to another. As Widor wrote on another occasion, Cavaillé-Coll’s new instruments require “a new language, an ideal other than scholastic polyphony. It is no longer the Bach of the Fugue whom we invoke, but the heart-rending melodist, the pre-eminently expressive master of the Prelude, the Magnificat, the B minor Mass, the Cantatas, and the St. Matthew Passion. Henceforth one will have to exercise the same care with the combination of timbres in an organ composition as in an orchestral work”. This fragment is crucial for understanding Widor’s aesthetics. Whilst his music, just as the organs he was playing, was indeed opening up a new era for the organ and its repertoire, it was not conceived as something simply “modern”. Widor was not turning his back to Bach, whom he had always revered, loved, and played (and of whom he also edited some pieces). Rather, he was turning from what he saw as Bach’s polyphonic style to a more Romantic concept of Baroqueness.

From Bach, Widor also learnt the possibility of weaving Church tunes within the texture of new works. Indeed, different from Bach, Widor was (ironically) not primarily a “church” musician, even though he spent more than sixty years of his life sitting at the organ of St.-Sulpice. He was not a “church” musician since his spiritual inspiration was less pronounced than Bach’s. But precisely in the two works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album does the ecclesiastical heritage become more apparent. Of Widor’s ten organ symphonies, these two are the only ones which are explicitly founded on Gregorian plainchant tunes. Written five years apart, respectively in 1895 and 1900, these two Symphonies have many points in common. They have fewer movements than the others, and are more tightly knitted. The “Gothic” Symphony derives its name from the Gothic Church of St. Ouen in Rouens, whilst the “Romane” Symphony similarly refers to the Romanesque Basilica of St. Sernin in Toulouse. Both churches had been just provided with one new Cavaillé-Coll each, and Widor’s symphonies celebrated the consecration and inauguration of their instruments. Their dedications refer to the two patron saints: “Ad memoriam Sancti Andoëni Rothomagensis” pays homage to the Latin name of both St. Ouen and the city of Rouens, whilst “Ad memoriam Sancti Saturnini Tolosensis” does the same with St. Sernin and Toulouse.

The earlier of these two symphonies was composed during the summer holidays of 1894, which Widor was spending on the Jura mountains. The work’s tonal plan is built on triadic relationships: from C minor to E-flat major, to G minor and to the concluding, shining C major. Here the plainchant tune which constitutes an important part of the thematic material is derived from the Introit for the fourth Christmas Day Mass, Puer natus est nobis. This symphony remained a special favourite of the composer, who always performed its first movement at All Saints’ Day (thus actually disregarding the connection between the plainchant tune and the liturgical occasion…).

The later symphony was completed five years later, again during summer, but, this time, at the Widors’ old home by Lyon. In this case, the generating plainchant tune is a Gradual for Easter Day, Haec dies, quam fecit Dominus. Thus these two great symphonies pay homage to the two greatest Christian holidays, i.e. Christmas and Easter. This tune is interwoven throughout the composition, but appears radiantly in the extraordinary Finale, which is unanimously acknowledged as one of Widor’s most impressive realisations.

Together, these two works represent possibly the crowning achievements of a genius of the organ, and of organ composition, and bear witness to the tight connection between means and inspiration, opportunity and creativity, availability and artistry.

Of course, Chopin favoured Pleyel pianos, but his works do not depend so dramatically on Pleyel pianos as Widor’s on Cavaillé-Coll organs. This is due to a number of reasons. Firstly, the difference between a Cavaillé-Coll organ and another organ of the same or of the preceding eras is incomparably more pronounced than that between a Pleyel and an Érard piano of the mid-nineteenth century. The difference between an earlier organ and a Cavaillé-Coll is more akin to that between Beethoven’s and Bruckner’s orchestras. And this is precisely because the Cavaillé-Coll organs developed a symphonic concept of the organ. Thus, it is not merely a matter of quantity (even if this does matter, when an unprecedented number of pipes and keyboards is involved), and not even just a matter of quality, but rather an almost ontological difference. Earlier organs and Cavaillé-Coll organs are like to evolutionary stages in a species. Secondly, the very idea of a symphonic organ is strictly bound, in a reciprocal influence, to that of an organ symphony, the genre Widor virtually created and which remains most closely associated with his compositional output. Thirdly, Widor’s symphonies were conceived, imagined, realised, and performed on these organs, and Widor’s six-decades long acquaintance with the organ of St.-Sulpice was crucial for the development of his repertoire and style. Fourthly, and not less importantly, Widor would hardly have had the opportunities he had to experiment, try, and create on those instruments, had it not been for Aristide Cavaillé-Coll’s encouragement, support, and active promotion.

Widor, indeed, was practically born on the organ loft. His father was an esteemed organist from Lyons, and began teaching his son very early. Thus, different from many other organists who moved their first steps as pianists and then moved to the organ (or added organ playing to their activity as pianists: this happened, for instance, with Saint-Saëns), Widor was “born” an organist. Already at eleven he was his father’s assistant and occasionally replaced him in his duties. Cavaillé-Coll was a family friend, and was quick to notice Charles-Marie’s precocious talent and innate predisposition for organ playing. Thanks to his good offices and influence, at nineteen Widor was accepted as a student by two of the greatest Belgian musicians of the era. In Brussels, in fact, Charles-Marie studied under the guidance of legendary organist Jacques Lemmens (1823-1881), and of the even more legendary François-Joseph Fétis, who was already in his eighties at the time. Fétis had been a leading figure of the European musical world, and represented a repository of compositional techniques and knowledge. The young man was eager to learn from him, and doubtlessly acquired from both teachers the ability which later characterized him.

But Aristide Cavaillé-Coll had not forgotten his protégé, nor abandoned him in Belgium. As soon as Widor’s education was accomplished, Cavaillé-Coll introduced him to the most important milieus of French- and French-speaking culture; thus, the young musician befriended such musicians as Saint-Saëns, César Franck, Meyerbeer, and foreign musicians such as Liszt and Rossini who lived in Paris. Widor’s career proceeded quickly and securely. At just twenty-four, he inaugurated the new, magnificent Cavaillé-Coll organ in the Cathedral Church of Notre Dame, along with six other organists. The following year, he participated in the inauguration of another Cavaillé-Coll organ at La Trinité (that organ, in the following century, would become inextricably associated with Olivier Messiaen). And just a few months later, Cavaillé-Coll, Gounod and Saint-Saëns (of whom Widor by then had become the assistant) managed an almost incredible coup. Upon the retirement of Louis James Alfred Lefébure-Wély, who had been the titular organist at St.-Sulpice, Widor’s influential friends secured for him the possibility of a provisional, one-year appointment as an organist in that church. That provisional, one-year appointment would last for six decades!

What should be noted is that the St.-Sulpice organ was the greatest and most impressive organ ever built by Cavaillé-Coll; it was an exceptional instrument, a masterpiece of technology and musicianship, and a rather intimidating monster with its unequalled size and power. That organ had been built in 1862, and comprised more than 100 stops, nearly 7000 pipes, 20 windchests, and the list could go on. As Widor would later recall, his symphonies could not have existed without that organ: “It was when I felt the pipes of the Saint-Sulpice organ vibrating under my hands and feet that I took to writing my first four organ symphonies. I did not seek any particular style or form. I wrote feeling them deeply, asking myself if they were inspired by Bach or Mendelssohn. No! I was listening to the sonorousness of Saint-Sulpice, and naturally I sought to extract from it a musical fabric – trying to make pieces that, while being free, featured some contrapuntal procedures”.

Whilst earlier organs, in fact, were conceived first and foremost in order to bring out the clarity of the polyphonic texture, and to let it emerge, the Cavaillé-Coll organs aimed rather at evoking the full palette of a modern symphonic orchestra, in terms of timbral variety, of dynamic range, and of flexibility in the transition from one dynamic level to another. As Widor wrote on another occasion, Cavaillé-Coll’s new instruments require “a new language, an ideal other than scholastic polyphony. It is no longer the Bach of the Fugue whom we invoke, but the heart-rending melodist, the pre-eminently expressive master of the Prelude, the Magnificat, the B minor Mass, the Cantatas, and the St. Matthew Passion. Henceforth one will have to exercise the same care with the combination of timbres in an organ composition as in an orchestral work”. This fragment is crucial for understanding Widor’s aesthetics. Whilst his music, just as the organs he was playing, was indeed opening up a new era for the organ and its repertoire, it was not conceived as something simply “modern”. Widor was not turning his back to Bach, whom he had always revered, loved, and played (and of whom he also edited some pieces). Rather, he was turning from what he saw as Bach’s polyphonic style to a more Romantic concept of Baroqueness.

From Bach, Widor also learnt the possibility of weaving Church tunes within the texture of new works. Indeed, different from Bach, Widor was (ironically) not primarily a “church” musician, even though he spent more than sixty years of his life sitting at the organ of St.-Sulpice. He was not a “church” musician since his spiritual inspiration was less pronounced than Bach’s. But precisely in the two works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album does the ecclesiastical heritage become more apparent. Of Widor’s ten organ symphonies, these two are the only ones which are explicitly founded on Gregorian plainchant tunes. Written five years apart, respectively in 1895 and 1900, these two Symphonies have many points in common. They have fewer movements than the others, and are more tightly knitted. The “Gothic” Symphony derives its name from the Gothic Church of St. Ouen in Rouens, whilst the “Romane” Symphony similarly refers to the Romanesque Basilica of St. Sernin in Toulouse. Both churches had been just provided with one new Cavaillé-Coll each, and Widor’s symphonies celebrated the consecration and inauguration of their instruments. Their dedications refer to the two patron saints: “Ad memoriam Sancti Andoëni Rothomagensis” pays homage to the Latin name of both St. Ouen and the city of Rouens, whilst “Ad memoriam Sancti Saturnini Tolosensis” does the same with St. Sernin and Toulouse.

The earlier of these two symphonies was composed during the summer holidays of 1894, which Widor was spending on the Jura mountains. The work’s tonal plan is built on triadic relationships: from C minor to E-flat major, to G minor and to the concluding, shining C major. Here the plainchant tune which constitutes an important part of the thematic material is derived from the Introit for the fourth Christmas Day Mass, Puer natus est nobis. This symphony remained a special favourite of the composer, who always performed its first movement at All Saints’ Day (thus actually disregarding the connection between the plainchant tune and the liturgical occasion…).

The later symphony was completed five years later, again during summer, but, this time, at the Widors’ old home by Lyon. In this case, the generating plainchant tune is a Gradual for Easter Day, Haec dies, quam fecit Dominus. Thus these two great symphonies pay homage to the two greatest Christian holidays, i.e. Christmas and Easter. This tune is interwoven throughout the composition, but appears radiantly in the extraordinary Finale, which is unanimously acknowledged as one of Widor’s most impressive realisations.

Together, these two works represent possibly the crowning achievements of a genius of the organ, and of organ composition, and bear witness to the tight connection between means and inspiration, opportunity and creativity, availability and artistry.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

Facebook

Twitter

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads