Tracklist:

1. Athina Valisakis – Reading for O Imittos (Mount Imittos) (00:16)

2. Pano Hora Ensemble – O Imittos (Mount Imittos) (03:17)

3. Athina Valisakis – Reading for Efige to Treno (The Train Left) (00:19)

4. Pano Hora Ensemble – Efige to Treno (The Train Left) (02:54)

5. Pano Hora Ensemble – Hassapiko Nostalgique (Nostalgic Hassapiko Dance) (05:23)

6. Athina Valisakis – Reading for Hartino to Fengaraki (Paper Moon) (00:20)

7. Pano Hora Ensemble – Hartino to Fengaraki (Paper Moon) (03:37)

8. Athina Valisakis – Reading for I Pikra Simera (The Bitterness Today) (00:34)

9. Pano Hora Ensemble – I Pikra Simera (The Bitterness Today) (03:44)

10. Athina Valisakis – Reading for Kyr' Adonis (Mr. Adonis) (00:35)

11. Pano Hora Ensemble – Kyr' Adonis (Mr. Adonis) (03:23)

12. Athina Valisakis – Reading for I Timoria (The Punishment) (00:20)

13. Pano Hora Ensemble – I Timoria (The Punishment) (02:51)

14. Athina Valisakis – Reading for Pame Mia Volta sto Fengari (Let's Take a Walk on the Moon) (00:18)

15. Pano Hora Ensemble – Pame Mia Volta sto Fengari (Let's Take a Walk on the Moon) (04:48)

16. Athina Valisakis – Reading for To Fengari Ine Kokino/To Triantafillo (Medley of The Moon Is Red/The Rose) (00:30)

17. Pano Hora Ensemble – To Fengari Ine Kokino/To Triantafillo (Medley of The Moon Is Red/The Rose) (03:44)

18. Athina Valisakis – Reading for Mikri Rallou (Little Rallou) (00:26)

19. Pano Hora Ensemble – Mikri Rallou (Little Rallou) (02:48)

20. Pano Hora Ensemble – Nikhterinos Peripatos (Evening Stroll) (03:53)

21. Athina Valisakis – Reading for Odos Oniron (Street of Dreams) (00:14)

22. Pano Hora Ensemble – Odos Oniron (Street of Dreams) (04:19)

23. Athina Valisakis – Reading for I Parthena tis Yitonias Mou (The Virgin in My Neighborhood) (00:14)

24. Pano Hora Ensemble – I Parthena tis Yitonias Mou (The Virgin in My Neighborhood) (03:36)

25. Athina Valisakis – Reading for S'agapo (I Love You) (00:18)

26. Pano Hora Ensemble – S'agapo (I Love You) (02:19)

27. Athina Valisakis – Reading for Lianotragouda (Couplets) (00:13)

28. Pano Hora Ensemble – Lianotragouda (Couplets) (03:05)

29. Athina Valisakis – Reading for To Mayico Hali (Magic Carpet) (00:31)

30. Pano Hora Ensemble – To Mayico Hali (Magic Carpet) (03:22)

For Muslims, a Hadj is a pilgrimage to Mecca. Orthodox Christians also use the word to recognize someone’s visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, or baptism in the Jordan. Manos Hadjidakis’s surname likely reflects some ancestor’s pilgrimage to one of those places. More importantly, his music has become something of a sacred destination, too. As a child in Washington, D.C., listening to his songs in the 1960s and 1970s, I could hear that they were different from the other Greek songs in our record collection. The poetic lyrics added an unfamiliar dimension, especially in his collaborations with the great poet, Nikos Gatzos. But other Greek songwriters, including the other internationally famous one of that period, Mikis Theodorakis, also made use of exquisite poetry. There is more to the unique, sacred feeling of Hadjidakis’s songs than their poetry’s beauty. Whether the subject is young love, lost love, a mountainous wilderness, the death of a girl, an evening’s stroll, or an eccentric old man living in a garden, they vividly bring to life specific people, moments and places, then transform them into something more. The frequent use of surrealistic imagery points in a mystical direction – the moon falls into a river, a prayer is fashioned from the hair of a beloved lady – but it is the music itself that elevates the scene in a manner akin to a hymn. Trying to describe how music produces feelings can only be a clumsy attempt to explain something ineffable. One cannot read one’s way to some destinations. One must visit them. The songs included here constitute a small fraction of Hadjidakis’s corpus, but span much of his most productive years, with selections from the 1940s to the 1970s, and represent each of the various genres in which his songs were featured. Some of the music first appeared in plays: Hartino to Fengaraki was written for the Greek production of A Streetcar Named Desire (1948), and To Triantafillo was written for Federico Garcia Lorca’s Doña Rosita (1959). Efige to Treno and Odos Oniron are from the 1962 musical, Odos Oniron. Six of the songs appeared in films, including To Fengari Ine Kokino from Stella (1955), O Imittos from Liza Has Run Away (1959), Pame Mia Volta Sto Fengari, Nikhterinos Peripatos and Hassapiko Nostalgique, from Never on Sunday (1960), and Mayico Hali, which is based on a melody originally written as the theme to Topkapi (1964). One of the songs, I Parthena Tis Yitonias Mou, from the album Gioconda’s Smile (1965), first appeared as an orchestral piece (with the narrative conveyed via program notes rather than lyrics). Hadjidakis also wrote song cycles, and two songs included here, S’agapo and Lianotragouda, are from perhaps his greatest song cycle, O Megalos Erotikos (1972). The rest were written as stand-alone popular songs, including I Timoria (1960), Kyr’ Adonis (1961), I Pikra Simera (1970) and Mikri Rallou (1970).

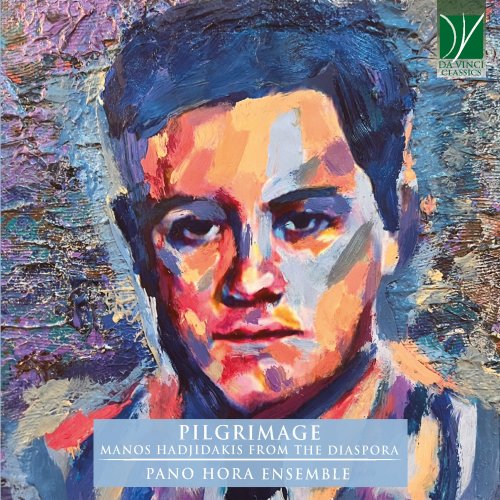

All of these have been recorded by Hadjidakis himself, and many of them have been recorded as instrumental arrangements more than once by Hadjidakis or his close associates – including in Hadjidakis’ famous albums, Fifteen Vespers (1964) and Thirty Nocturnes (1987), and Nikos Kypourgos’ The Other Marketplace (1998). Not to mention the countless recordings by Greek and other artists of vocal versions of his songs, including the beautiful 1983 collaboration of Lena Platonos and Savina Yannatou, To ’62 Tou Manou Hadjidaki. Many of those recordings, including all the albums listed here, are classics. Why create another collection now? One reason to record covers of great songs, I suppose, is the passage of time. Despite Hadjidakis’s fame, I encounter many people, even professional musicians, who are not familiar with his music. That may seem strange to those who followed his career. He produced an uncountable number of great songs, and was well known in America, where he lived for five years (in the early years of the Greek dictatorship), won an Academy Award, had one of his most famous albums (Gioconda’s Smile) produced by Quincy Jones, and saw his songs recorded with the original Greek lyrics by such legendary American performers as Nat King Cole and Harry Belafonte. (Yes, popular music used to be like that.) Nevertheless, it has been several decades since those things happened. New covers may open a door to his music for some who don’t already know it and might not otherwise stumble upon it. Apart from such practical rationalizations, another reason is simply personal. After experiencing Hadjidakis’s music for over fifty years, I wanted to climb inside my favorite songs in a new way, not to reinvent them, but rather to hear what can happen when they are arranged for a small and novel ensemble. I hope those that love his music will not hold shortcomings that reflect the limitations of my hearing against me. I don’t think Hadjidakis (who once said that every song is a game) would mind. He certainly understood such a need, if not such limitations. He recorded instrumental covers of many of the most important compositions of his youth, reflecting pilgrimages to his own rebetiko roots in the masterpieces, Lilacs Out of the Dead Land (1961), and The Cruel April of 1945 (1972). And he collaborated as a pianist with the great singer, Flery Dadonaki, in the stunning Liturgica (1970), part of which was dedicated to classic rebetiko covers and part to Hadjidakis’s own songs. Writing about his 1940s experience of rebetiko in the notes to Lilacs, Hadjidakis must have known that he also was summarizing his own effect on a generation of listeners: “dazed by the grandeur and depth of the melodic phrases, a stranger to them, young and without strength, I believed suddenly that the song I was listening to was my own, utterly my own story.” Great songs become everyone’s property. I remember on a ferry to Naxos about twenty years ago listening to two grandparents sweetly sing Hartino to Fengaraki to their granddaughter. Think about the effect on a young child of the line “if you had believed me even a little, it all would have been true.” More delightful words have never been heard by a granddaughter. That song became hers forever, just as it was theirs.It also occurs to me that Hadjidakis might have liked the idea of having his compositions reflected in a multi-cultural mirror of American musicians. He collaborated with the great director, Elia Kazan in the film masterpiece America America (1963), which among its other themes explored the conception of America in the Greek psyche. Later, during his five years living in New York, Hadjidakis experienced America as an immigrant. Perhaps it was not a coincidence that he worked on O Megalos Erotikos, arguably his most profound reflection on Greek culture, during his time in New York. It might even be argued that the distance from Greece during those years in New York helped to highlight what was essential and common in the Greek love poetry of the ages that he wove together in that remarkable work. In arranging these songs and producing this album I incurred many debts, most obviously to the accomplished musicians who came together to form the Pano Hora Ensemble: Erzsi Gódor, Ginevra Petrucci, Ljova Zhurbin, Oren Fader, and Jay Elfenbein; to Daniel Zinn, who managed and conducted the rehearsals and recording sessions, and to Godfrey Furchtgott, who engineered the mixes so skillfully. Ginevra Petrucci painted the beautiful portrait of Hadjidakis that appears on the cover of the album. I am also grateful to Athina Vasilakis, whose voice can be heard reading brief excerpts from the lyrics in Greek and English before each song, to David Rozenblatt, who offered helpful ideas on several of the orchestrations, to the pianist, Beyza Yazgan, who sat in during rehearsals prior to Erzsi’s arrival from Budapest, to Nick Tolle, who brought us his cimbalom from Boston, to Garrett DeBlock, the recording engineer at Brooklyn’s Strange Weather Studio, where the songs were recorded in December 2021, and to Alan Silverman, who engineered the master. I am grateful to my wife, Nancy, for encouraging me throughout the process, to my late father, William (Vasilis), for maintaining a collection of Greek albums and playing them incessantly, to my late mother, Mary, for tirelessly writing out and explaining Greek song lyrics to me, and to God for bringing all of these people into my life and making this journey possible.

Charles Calomiris, New York, January 2022