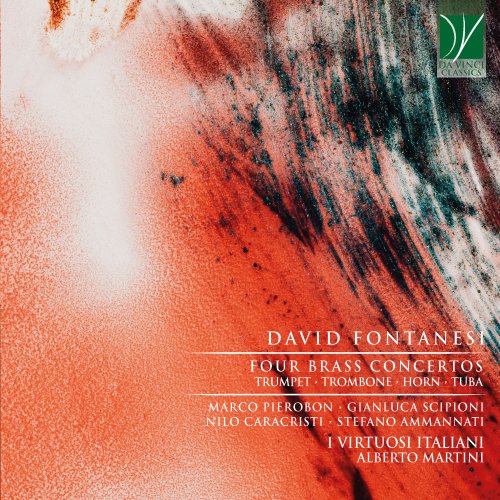

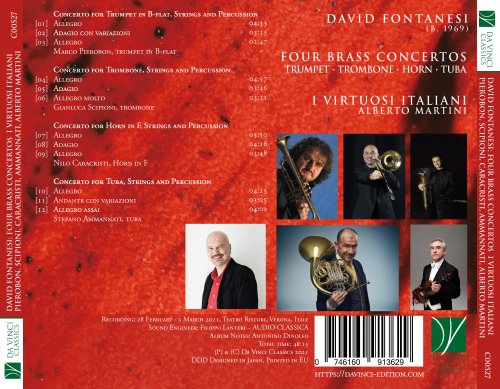

Marco Pierobon, Nilo Caracristi, Alberto Martini, I Virtuosi Italiani - Fontanesi: Four Brass Concert (Trumpet, Trombone, Horn, Tuba) (2022)

BAND/ARTIST: Marco Pierobon, Nilo Caracristi, Alberto Martini, I Virtuosi Italiani

- Title: Fontanesi: Four Brass Concert (Trumpet, Trombone, Horn, Tuba)

- Year Of Release: 2022

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 00:48:20

- Total Size: 250 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Concerto for Trumpet, Strings and Percussion in B-Flat Major: I. Allegro

02. Concerto for Trumpet, Strings and Percussion in B-Flat Major: II. Adagio con variazioni

03. Concerto for Trumpet, Strings and Percussion in B-Flat Major: III. Allegro

04. Concerto for Trombone, Strings and Percussion: I. Allegro

05. Concerto for Trombone, Strings and Percussion: II. Adagio

06. Concerto for Trombone, Strings and Percussion: III. Allegro molto

07. Concerto for Horn, Strings and Percussion in F Major: I. Allegro

08. Concerto for Horn, Strings and Percussion in F Major: II. Adagio

09. Concerto for Horn, Strings and Percussion in F Major: III. Allegro

10. Concerto for Tuba, Strings and Percussion: I. Allegro

11. Concerto for Tuba, Strings and Percussion: II. Andante con variazioni

12. Concerto for Tuba, Strings and Percussion: III. Allegro assai

The four concertos here recorded constitute a tribute to the brass family, in which David Fontanesi makes a very specific commitment: to explore the timbral, technical and expressive peculiarities of these instruments without ever losing sight of the main object of gratifying the listener. Over and above certain formal similarities, the main feature the four works share is the very essence of their style: a style that always abstains from ambiguous experimentalism and instead draws heavily on the legacy of the great masters of the past. Yet if the greatness of a composition is distinguished in some way also by its originality, with good reason we can assert that the four concertos are original precisely because they innovate the instrumental language of the classical tradition without ever undermining its basic grammatical foundations. By adopting certain very personal solutions the composer successfully achieves his aim of surprising his audience, though he does so within a solid framework that has a strong aesthetic and emotional impact. In this way he ensures that his works can be enjoyed and appreciated by an extremely broad audience, ranging from the relatively inexperienced to the more practised listener. The former will derive immediate delight purely from the emotional appeal created by the flow of the music itself. The more seasoned listener, on the other hand, will find satisfaction in the intellectual curiosity generated by a hypertextual structure dense with references to different periods, though often nuanced by the composer’s distinctive style.

One characteristic of the four concertos that instantly betrays a more modern taste is the composer’s recourse to a wide selection of percussion instruments, here used in various ways to punctuate and invigorate the dialogue between the solo instrument and the strings. An original stylistic approach, however, is also apparent in the subtle handling of all the constituent elements of musical creation, with results that are pleasing to the ear. Particularly deserving of mention are the elegant melodic lines written for the solo instruments. This might seem surprising, since melodic invention, unlike the other elements of the musical edifice, is the feature least subjected to specific rules of composition, so it testifies to the sensitive way Fontanesi alludes to a very wide range of melodic styles. In the manner of a skilled craftsman, he shapes his melodies with taste and naturalness, seemingly making them emerge from the very technique of the solo instrument. And with their oscillations between moments of tension and relaxation, the melodic contours of the solo parts confer on the various concertos movements an undeniable narrative character that beguiles the listener. The concertos recorded here adopt the traditional three-movement form used in Vivaldi’s day, and it is within this basic framework that the refined musical narratives unfold. The use of the same overall formal elements also implies the frequent recourse to certain compositional procedures and techniques that confer a further degree of unity on the four works. Another unifying element is the makeup of the orchestral forces, which consist of strings and those same percussion instruments (timpani, triangle, suspended cymbal, tom toms, woodblocks. xylophone, side drum): a specific grouping that clearly allows Fontanesi to find an ideal balance in the solo-tutti dialect. A final common feature worth mentioning is the refinement of the contrapuntal writing in many parts of the present works, which can be seen as a mature reworking of the great polyphonic tradition.

The first work in this ‘musical polyptych’ is the Concerto for Trumpet in B flat, Strings and Percussion. In the Allegro, 1the opening statement of the main theme is immediately repeated by the trumpet and then developed in various ways using sequences, double canons and other contrapuntal artifices. The home key of B minor is contrasted by modulations to neighbouring keys. A sense of cohesion and solidity is conveyed to the whole movement by the returns of the strongly characterised main theme and the frequent allusions to it, while echoes of Vivaldi are suggested by the presence of sequences and repeated-note patterns. The melodic writing, featuring a succession of rapid and incisive statements, is particularly suited to the expressive potential of the solo instrument. Delightful and well-contextualised are the quasi-cinematic allusions to the shuffling of horse-hooves by the three woodblocks. The Adagio con variazioni is the movement that highlights the element of contrast. The calm pace of the theme entrusted to the trumpet, in the home key of D major, further develops the cinematic quality noticed in the preceding movement, for the idea of a 20th-century film score is strongly suggested by the theme’s interval structure and its broad sonorities sustained by the accompaniment of the strings. Also of considerable impact is the handling of the tonal organisation: the more discerning listener will succeed in detecting the shifts in melodic and harmonic balance at the transition from D major to the Dorian church mode, introducing a passage as unusual as it is beguiling. The third movement, while adopting a different approach, harks back to the atmosphere of the first movement with a return tof the key of B minor. It unfolds as a fugato movement with its three parts presented by the double basses, trumpet and second violins, with embellished doublings provided by the cellos, violas and first violins. The fugal development is duly interspersed with sequences and free episodes, at times embellished of the percussion.

The Concerto for Trombone, Strings and Percussion marks the appearance of softer and more subdued sonorities on the part of the soloist. The opening Allegro in C major is based on the elaboration of a single theme that is subjected to successive developments using sequences, modulations to neighbouring keys and other features such as multiple and double canons that expose the composer’s skill in the art of counterpoint. Even the less expert listener will surely appreciate the complexity of the structure by observing how the many melodic lines either go their own different ways to create intricate patterns or merge together at the moments of greater stasis. The animated discourse of the first movement is then followed by an Adagio of a nostalgic character, a wonderful musical elegy in A minor delivered with great elegance by the trombone. Right from the start a sense of measured movement is effectively conveyed by the steady pace in 6/8 time and the stable texture of the orchestral support. The discrete trombone glissandi (both ascending and descending) add a further touch of refinement to this exquisite musical picture. The closing third movement, an Allegro molto back in the key of C major, launches into a four-part fugato in which the trombone, by providing an added bass line, evokes the monumental atmosphere typical of Baroque organ works.

A partially syncopated theme, woven over a distinctly lively harmonic texture, introduces the Allegro of the Concerto for Horn in F, Strings and Percussion. Various factors bring to mind a Mozartian model: in particular, the choice of E flat major as the home key, the presence of rapid semiquavers with stepwise movement in the solo part, and the symmetry of the thematic segments, as well as other more elusive aspects. Further allusions to the Classical style can also be detected in the restatement of the theme in the minor mode and in certain modulating passages. At the same time, however, a more decidedly 20th-century idiom can be detected in the greater mobility of the harmonic language, generating continual inflections of the theme played by the soloist: characteristics that would even seem to bring to mind the experience of Shostakovich. The horn is exploited throughout its range, from the low, dark sounds of the bottom register to the brightest top notes, while the player’s skill is severely put to the test both by these widely shifting registers and the execution of rapid passages. The xylophone is entrusted with the important role of anticipating or echoing the horn in the statement of the semiquaver patterns, thereby reinforcing the structural coherence of this movement. Right from the introduction for strings, the following Adagio, in the key of D minor, evokes the slow movements of Telemann’s concertos for horn, strings and continuo. This is a sensation confirmed by the horn part and its tranquil theme of great delicacy, consisting mainly of notes that proceed by step. It is a theme that permits the horn player to draw out the full timbral and expressive qualities of the instrument, achieving moments of intense lyricism. The sorrowful progress of the solo part is underscored by a repeated figure (of short phrases ending with an acciaccatura) assigned to the first violins, a further evocation of the Baroque style, in accord with the overall atmosphere. The final Allegro, which is back in the key of E flat major, presents a three-part fugato introduced by the double basses, solo horn and seconds violins with embellished doublings on the cellos, violas and first violins. In this movement one has the sensation that the more animated theme entrusted to the horn is intimately connected, at an artistic level, to the compositional procedure of the fugue: it is as if the main creative idea was suggested to the composer by fugal writing itself, with its dialectics and constraints.

The series of four concertos closes with the low sonorities of the Concerto for Tuba, Strings and Percussion. The first movement, in the key of D minor, opens with regular semiquaver movement on the strings (strongly reminiscent of Vivaldi), over which the tuba introduces the main theme. The entire movement is centred on the masterly elaboration of this same thematic nucleus using sequences, modulations to neighbouring keys and diverse contrapuntal artifices. The same materials are then restated in the major key. Moments of great pathos are also generated by the three-way dialogue between the tuba, strings and percussion. The second movement, an Andante con variazioni, is based on a series of variations that involve not only the theme and accompaniment but also the tonality, which undergoes repeated transformations before returning to the home key of F major at the end of the piece. This wonderful concerto closes with an Allegro in the key of D minor consisting of a complex four-part fugato with the tuba soloist providing an additional bass line. Over the somewhat complex writing for the strings and percussion there are moments in which solo instrument gracefully engages in challenging virtuoso passages. The music is developed by frequent recourse to modulations to neighbouring keys, sequences accompanied by the percussion, and canons. With the exception of a few moments where the instrumental forces are reduced, the contrapuntal texture is always dense and progresses with great vigour right up to the majestic conclusion.

With these four works Fontanesi achieves extraordinary levels of stylistic and expressive force. And in spite of their individual differences, the four concertos are admirably homogeneous in qualitative terms. Their merit seems to stem from an incessant search for Beauty: a distinct commitment that the composer makes with his audiences. Such consideration for his public is also apparent in the fact that his pieces are never too long, as perhaps a way of acknowledging the propensities of the contemporary listener. And with his avoidance of the long-drawn-out movement he succeeds in creating structures that are complete in themselves and devoid of redundance and prolixity. For these very qualities these concertos will undoubtedly constitute a rich contribution to the classical concert literature of the 21st century.

01. Concerto for Trumpet, Strings and Percussion in B-Flat Major: I. Allegro

02. Concerto for Trumpet, Strings and Percussion in B-Flat Major: II. Adagio con variazioni

03. Concerto for Trumpet, Strings and Percussion in B-Flat Major: III. Allegro

04. Concerto for Trombone, Strings and Percussion: I. Allegro

05. Concerto for Trombone, Strings and Percussion: II. Adagio

06. Concerto for Trombone, Strings and Percussion: III. Allegro molto

07. Concerto for Horn, Strings and Percussion in F Major: I. Allegro

08. Concerto for Horn, Strings and Percussion in F Major: II. Adagio

09. Concerto for Horn, Strings and Percussion in F Major: III. Allegro

10. Concerto for Tuba, Strings and Percussion: I. Allegro

11. Concerto for Tuba, Strings and Percussion: II. Andante con variazioni

12. Concerto for Tuba, Strings and Percussion: III. Allegro assai

The four concertos here recorded constitute a tribute to the brass family, in which David Fontanesi makes a very specific commitment: to explore the timbral, technical and expressive peculiarities of these instruments without ever losing sight of the main object of gratifying the listener. Over and above certain formal similarities, the main feature the four works share is the very essence of their style: a style that always abstains from ambiguous experimentalism and instead draws heavily on the legacy of the great masters of the past. Yet if the greatness of a composition is distinguished in some way also by its originality, with good reason we can assert that the four concertos are original precisely because they innovate the instrumental language of the classical tradition without ever undermining its basic grammatical foundations. By adopting certain very personal solutions the composer successfully achieves his aim of surprising his audience, though he does so within a solid framework that has a strong aesthetic and emotional impact. In this way he ensures that his works can be enjoyed and appreciated by an extremely broad audience, ranging from the relatively inexperienced to the more practised listener. The former will derive immediate delight purely from the emotional appeal created by the flow of the music itself. The more seasoned listener, on the other hand, will find satisfaction in the intellectual curiosity generated by a hypertextual structure dense with references to different periods, though often nuanced by the composer’s distinctive style.

One characteristic of the four concertos that instantly betrays a more modern taste is the composer’s recourse to a wide selection of percussion instruments, here used in various ways to punctuate and invigorate the dialogue between the solo instrument and the strings. An original stylistic approach, however, is also apparent in the subtle handling of all the constituent elements of musical creation, with results that are pleasing to the ear. Particularly deserving of mention are the elegant melodic lines written for the solo instruments. This might seem surprising, since melodic invention, unlike the other elements of the musical edifice, is the feature least subjected to specific rules of composition, so it testifies to the sensitive way Fontanesi alludes to a very wide range of melodic styles. In the manner of a skilled craftsman, he shapes his melodies with taste and naturalness, seemingly making them emerge from the very technique of the solo instrument. And with their oscillations between moments of tension and relaxation, the melodic contours of the solo parts confer on the various concertos movements an undeniable narrative character that beguiles the listener. The concertos recorded here adopt the traditional three-movement form used in Vivaldi’s day, and it is within this basic framework that the refined musical narratives unfold. The use of the same overall formal elements also implies the frequent recourse to certain compositional procedures and techniques that confer a further degree of unity on the four works. Another unifying element is the makeup of the orchestral forces, which consist of strings and those same percussion instruments (timpani, triangle, suspended cymbal, tom toms, woodblocks. xylophone, side drum): a specific grouping that clearly allows Fontanesi to find an ideal balance in the solo-tutti dialect. A final common feature worth mentioning is the refinement of the contrapuntal writing in many parts of the present works, which can be seen as a mature reworking of the great polyphonic tradition.

The first work in this ‘musical polyptych’ is the Concerto for Trumpet in B flat, Strings and Percussion. In the Allegro, 1the opening statement of the main theme is immediately repeated by the trumpet and then developed in various ways using sequences, double canons and other contrapuntal artifices. The home key of B minor is contrasted by modulations to neighbouring keys. A sense of cohesion and solidity is conveyed to the whole movement by the returns of the strongly characterised main theme and the frequent allusions to it, while echoes of Vivaldi are suggested by the presence of sequences and repeated-note patterns. The melodic writing, featuring a succession of rapid and incisive statements, is particularly suited to the expressive potential of the solo instrument. Delightful and well-contextualised are the quasi-cinematic allusions to the shuffling of horse-hooves by the three woodblocks. The Adagio con variazioni is the movement that highlights the element of contrast. The calm pace of the theme entrusted to the trumpet, in the home key of D major, further develops the cinematic quality noticed in the preceding movement, for the idea of a 20th-century film score is strongly suggested by the theme’s interval structure and its broad sonorities sustained by the accompaniment of the strings. Also of considerable impact is the handling of the tonal organisation: the more discerning listener will succeed in detecting the shifts in melodic and harmonic balance at the transition from D major to the Dorian church mode, introducing a passage as unusual as it is beguiling. The third movement, while adopting a different approach, harks back to the atmosphere of the first movement with a return tof the key of B minor. It unfolds as a fugato movement with its three parts presented by the double basses, trumpet and second violins, with embellished doublings provided by the cellos, violas and first violins. The fugal development is duly interspersed with sequences and free episodes, at times embellished of the percussion.

The Concerto for Trombone, Strings and Percussion marks the appearance of softer and more subdued sonorities on the part of the soloist. The opening Allegro in C major is based on the elaboration of a single theme that is subjected to successive developments using sequences, modulations to neighbouring keys and other features such as multiple and double canons that expose the composer’s skill in the art of counterpoint. Even the less expert listener will surely appreciate the complexity of the structure by observing how the many melodic lines either go their own different ways to create intricate patterns or merge together at the moments of greater stasis. The animated discourse of the first movement is then followed by an Adagio of a nostalgic character, a wonderful musical elegy in A minor delivered with great elegance by the trombone. Right from the start a sense of measured movement is effectively conveyed by the steady pace in 6/8 time and the stable texture of the orchestral support. The discrete trombone glissandi (both ascending and descending) add a further touch of refinement to this exquisite musical picture. The closing third movement, an Allegro molto back in the key of C major, launches into a four-part fugato in which the trombone, by providing an added bass line, evokes the monumental atmosphere typical of Baroque organ works.

A partially syncopated theme, woven over a distinctly lively harmonic texture, introduces the Allegro of the Concerto for Horn in F, Strings and Percussion. Various factors bring to mind a Mozartian model: in particular, the choice of E flat major as the home key, the presence of rapid semiquavers with stepwise movement in the solo part, and the symmetry of the thematic segments, as well as other more elusive aspects. Further allusions to the Classical style can also be detected in the restatement of the theme in the minor mode and in certain modulating passages. At the same time, however, a more decidedly 20th-century idiom can be detected in the greater mobility of the harmonic language, generating continual inflections of the theme played by the soloist: characteristics that would even seem to bring to mind the experience of Shostakovich. The horn is exploited throughout its range, from the low, dark sounds of the bottom register to the brightest top notes, while the player’s skill is severely put to the test both by these widely shifting registers and the execution of rapid passages. The xylophone is entrusted with the important role of anticipating or echoing the horn in the statement of the semiquaver patterns, thereby reinforcing the structural coherence of this movement. Right from the introduction for strings, the following Adagio, in the key of D minor, evokes the slow movements of Telemann’s concertos for horn, strings and continuo. This is a sensation confirmed by the horn part and its tranquil theme of great delicacy, consisting mainly of notes that proceed by step. It is a theme that permits the horn player to draw out the full timbral and expressive qualities of the instrument, achieving moments of intense lyricism. The sorrowful progress of the solo part is underscored by a repeated figure (of short phrases ending with an acciaccatura) assigned to the first violins, a further evocation of the Baroque style, in accord with the overall atmosphere. The final Allegro, which is back in the key of E flat major, presents a three-part fugato introduced by the double basses, solo horn and seconds violins with embellished doublings on the cellos, violas and first violins. In this movement one has the sensation that the more animated theme entrusted to the horn is intimately connected, at an artistic level, to the compositional procedure of the fugue: it is as if the main creative idea was suggested to the composer by fugal writing itself, with its dialectics and constraints.

The series of four concertos closes with the low sonorities of the Concerto for Tuba, Strings and Percussion. The first movement, in the key of D minor, opens with regular semiquaver movement on the strings (strongly reminiscent of Vivaldi), over which the tuba introduces the main theme. The entire movement is centred on the masterly elaboration of this same thematic nucleus using sequences, modulations to neighbouring keys and diverse contrapuntal artifices. The same materials are then restated in the major key. Moments of great pathos are also generated by the three-way dialogue between the tuba, strings and percussion. The second movement, an Andante con variazioni, is based on a series of variations that involve not only the theme and accompaniment but also the tonality, which undergoes repeated transformations before returning to the home key of F major at the end of the piece. This wonderful concerto closes with an Allegro in the key of D minor consisting of a complex four-part fugato with the tuba soloist providing an additional bass line. Over the somewhat complex writing for the strings and percussion there are moments in which solo instrument gracefully engages in challenging virtuoso passages. The music is developed by frequent recourse to modulations to neighbouring keys, sequences accompanied by the percussion, and canons. With the exception of a few moments where the instrumental forces are reduced, the contrapuntal texture is always dense and progresses with great vigour right up to the majestic conclusion.

With these four works Fontanesi achieves extraordinary levels of stylistic and expressive force. And in spite of their individual differences, the four concertos are admirably homogeneous in qualitative terms. Their merit seems to stem from an incessant search for Beauty: a distinct commitment that the composer makes with his audiences. Such consideration for his public is also apparent in the fact that his pieces are never too long, as perhaps a way of acknowledging the propensities of the contemporary listener. And with his avoidance of the long-drawn-out movement he succeeds in creating structures that are complete in themselves and devoid of redundance and prolixity. For these very qualities these concertos will undoubtedly constitute a rich contribution to the classical concert literature of the 21st century.

Year 2022 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads