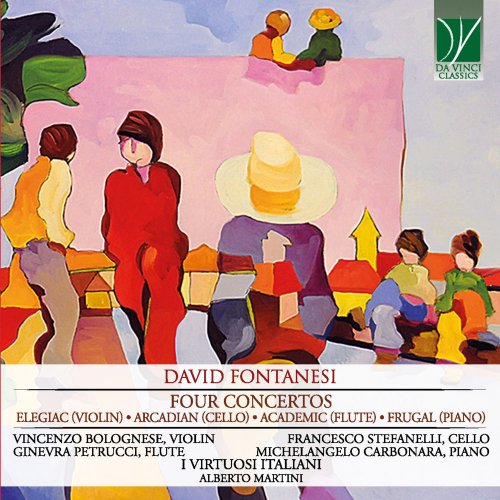

Alberto Martini, Francesco Stefanelli, Ginevra Petrucci, I Virtusi Italiani, Michelangelo Carbonara, Vincenzo Bolognese - David Fontanesi: Four Concertos (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Alberto Martini, Francesco Stefanelli, Ginevra Petrucci, I Virtusi Italiani, Michelangelo Carbonara, Vincenzo Bolognese

- Title: David Fontanesi: Four Concertos - Elegiac (Violin), Arcadian (Cello), Academic (Flute), Frugal (Piano)

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 01:04:14

- Total Size: 302 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Elegiac Concert I. Allegro Appassionato

02. Elegiac Concert II. Adagio molto

03. Elegiac Concert III. Vivace

04. Arcadian Concert I. Allegro Moderato

05. Arcadian Concert II. Poco adagio

06. Arcadian Concert III. Allegro agitato

07. Academic Concert I. Allegro Moderato

08. Academic Concert II. Adagio espressivo

09. Academic Concert III. Vivace

10. Frugal Concert I. Allegro Moderato

11. Frugal Concert II. Adagio

12. Frugal Concert III. Presto

The tendency of music critics, and more generally art critics, to find connections and lines of influence linking a certain composer or specific work with real or presumed predecessors (towards which the artistic creation in question is supposed to be, in some respect, indebted), is a game of cross-referencing that is as intriguing as it is dangerous. It is intriguing, since part of a work’s meaning can be understood only by comparing it to other composers’ works, with which it engages in a conversation (more or less consciously as the case may be), and by which its aesthetic and cultural coordinates are defined. But it is dangerous when the whole edifice of comparisons erected to describe the work in question becomes too close-fitting, suffocates its most intimate nature and risks failing to do justice to its formal, expressive and stylistic qualities.

If one wished to apply this sort of procedure to the four recent concertos of David Fontanesi ‒ while paying careful attention not to expose oneself to the hazards mentioned above ‒ one would find oneself right in the middle of an apparently inextricable tangle, so many are the references (both the hidden allusions and those more openly stated) and the stylistic connections that shape the substance of these works, written in the two-year period 2016-17. Wishing to approach the matter in chronological order, and arbitrarily limiting our research to the Italian peninsula, the first example that comes to mind is that of Antonio Vivaldi’s famous Four Seasons: either for mere reasons of number and macro-structure, or, more specifically, because we find the composer returning to that idea of dialogue between instruments that was so widely developed in the concerto of the 17th and 18th centuries. There is, however, not a trace in Fontanesi of the programmatic or descriptive intentions we find there. So it would perhaps be more pertinent to consider the so-called Generation of the Eighties, and especially those works – like Malipiero’s Cimarosiana or Casella’s Scarlattiana ‒ that represent that recovery of the antique, and of instrumental and polyphonic music in particular, from which modern Italian music was supposed to take its cue. But even in this case, it is worth noting that Fontanesi does not directly quote thematic sources from the Italian classical tradition; instead, the inspiration he draws from such works is to reassert universal values such as those of formal unity and contrapuntal complexity.

Most likely, therefore, a more fitting way of pinning down these works is to link them to Franco Margola, a composer who is particularly dear to Fontanesi (who, it is perhaps worth remembering, curated the critical edition of Margola’s Quartet no. 7 for flute and strings). With Margola he shares the same desire to engage in a sort of neo-Baroquism purged of ideological pronouncements, whose apparent austerity is tempered by post-Romantic nostalgias and instances of subtle irony. But what they share to an even greater degree – over and above the obvious stylistic differences, given that Fontanesi lacks that modernist angularity (caused by the superimposition of different surfaces in a way reminiscent of synthetic cubism) that characterises Margola’s aesthetic approach ‒ is a specific idea of the composer’s craft. This ‒ to quote the words once used by the older master ‒ should be understood as a “silent craftsmanship that, in absolute modesty, operates in a way that is free of clamour and polemic”.

The general form of the works performed here, as has already been suggested, owes much to the format of the Baroque concerto, with a middle Andante movement placed between two Allegros. The formal concision we sometimes encounter does not prevent Fontanesi from presenting an abundant variety of melodic ideas, rhythmic inventions and unexpected modulations, though always within the bounds of an admirable structural clarity. Exemplary, in this sense, is the ‘Arcadian’ concerto for cello, with the solo instrument entrusted with the statement and development of a melodic line of great emotional vigour, that passes through various expressive landscapes as it follows the carefully planned key transitions from minor to major. The opening of the second movement, presented by the oboe and strings, transports us to an oneiric dimension, amplified by the songlike melodic phrases of the solo instrument. A refrain, which harks back to the main theme of the third movement of Khachaturian’s Cello Concerto (from the rhythmic point view and in its orchestration), sets the tempo of the final rondo, driving it through virtuosic cadenzas and orchestral crescendos to a finale of great intensity.

The Concerto for piano – called the ‘Frugal’, perhaps to underline its immediate appeal, in spite of a compositional style that is particularly refined and rich in interesting details (both formal and timbral) ‒ seems to bounce happily between the 19th and 20th centuries. For while the grandiose orchestral section and the virtuoso piano-playing displayed in the second movement hark back to late-romantic utterings, the radiance of the syncopated string and woodwind chords and the lively piano figurations that typify the brilliant outer movements transport us to the neoclassical world of the early 20th century, enriching the discourse with scintillating interactions between piano, percussion and (especially in the final movement) flute.

At times – it is the case, for example, in the first two movements of the Concerto for violin, called the ‘Elegiac’ – the composer embraces larger forms, which he exploits to develop to the utmost the broadly conceived themes played by the solo instrument, in a lively dialogue with the patterns of the accompanying orchestra; whereas in the final movement the violinist is called upon to answer, with flashes of virtuosity, the powerful orchestral chords that repeatedly affirm their presence.

Even longer is the first movement of the Flute concerto, which opens with an extended orchestral exposition, which is anything but merely introductory, given the wealth of thematic material and the contrapuntal density displayed. The entrance of the soloist is artfully delayed in the manner of the classical composers, who saw this as a particular source of pleasure for the audience. Yet listeners are here also provided with more sophisticated forms of gratification: like that of following the exposition and development of the various themes and participating in the close dialogue between soloist and orchestra. In this work, which the composer significantly labels as ‘Academic’, the classical style is also evoked in the measured emotional tone that pervades it, the admirable formal balance that sustains it, and the taut polyphonic strands that run through it. At the same time, however, the music allows itself pleasant distractions, particularly the melodies assigned to the flute, which are as relaxed and dreamlike in the second movement as they are swirling and vivacious in the rhythmically charged final movement.

Alongside the well-proportioned compositional framework, which conceals within it an abundance of syntactic nuances and shifting blends of timbre, what these four concertos have in common, from the emotional point of view, is the prevalence of idyllic and nostalgic tones that combine and alternate. In this way they project the mental image of an arcadia that is intangible, but ‒ as Friedrich Schiller had already theorised in his dissertation on the naïve and sentimental, towards the end of the 18th century ‒ still present, at least as an ideal goal, in our aspirations as inhabitants of modernity. Is this contemporary music? If one follows the commonly held opinion, that the contemporary must speak exclusively of present-day reality, and especially of its most decadent, degrading and dangerous facets ‒ a fashionable notion that has also taken root in the other art forms, and that insists, for example, that an artist should be classified as authentically “contemporary” only if his/her works duly express feelings such as unease, alienation and angst ‒ in that case the answer is no. But I believe it is high time to free ourselves of these stale clichés, in favour of an approach that may also capture the positive aspects of our being in the world and the gratifying experiences ‒ even through artistic (and specifically musical) creation ‒ that it can offer us. Among these, we should include the experience of listening to David Fontanesi’s concertos, which, with their refined outdatedness, are among the most genuine and seductive within the variegated panorama of contemporary music.

01. Elegiac Concert I. Allegro Appassionato

02. Elegiac Concert II. Adagio molto

03. Elegiac Concert III. Vivace

04. Arcadian Concert I. Allegro Moderato

05. Arcadian Concert II. Poco adagio

06. Arcadian Concert III. Allegro agitato

07. Academic Concert I. Allegro Moderato

08. Academic Concert II. Adagio espressivo

09. Academic Concert III. Vivace

10. Frugal Concert I. Allegro Moderato

11. Frugal Concert II. Adagio

12. Frugal Concert III. Presto

The tendency of music critics, and more generally art critics, to find connections and lines of influence linking a certain composer or specific work with real or presumed predecessors (towards which the artistic creation in question is supposed to be, in some respect, indebted), is a game of cross-referencing that is as intriguing as it is dangerous. It is intriguing, since part of a work’s meaning can be understood only by comparing it to other composers’ works, with which it engages in a conversation (more or less consciously as the case may be), and by which its aesthetic and cultural coordinates are defined. But it is dangerous when the whole edifice of comparisons erected to describe the work in question becomes too close-fitting, suffocates its most intimate nature and risks failing to do justice to its formal, expressive and stylistic qualities.

If one wished to apply this sort of procedure to the four recent concertos of David Fontanesi ‒ while paying careful attention not to expose oneself to the hazards mentioned above ‒ one would find oneself right in the middle of an apparently inextricable tangle, so many are the references (both the hidden allusions and those more openly stated) and the stylistic connections that shape the substance of these works, written in the two-year period 2016-17. Wishing to approach the matter in chronological order, and arbitrarily limiting our research to the Italian peninsula, the first example that comes to mind is that of Antonio Vivaldi’s famous Four Seasons: either for mere reasons of number and macro-structure, or, more specifically, because we find the composer returning to that idea of dialogue between instruments that was so widely developed in the concerto of the 17th and 18th centuries. There is, however, not a trace in Fontanesi of the programmatic or descriptive intentions we find there. So it would perhaps be more pertinent to consider the so-called Generation of the Eighties, and especially those works – like Malipiero’s Cimarosiana or Casella’s Scarlattiana ‒ that represent that recovery of the antique, and of instrumental and polyphonic music in particular, from which modern Italian music was supposed to take its cue. But even in this case, it is worth noting that Fontanesi does not directly quote thematic sources from the Italian classical tradition; instead, the inspiration he draws from such works is to reassert universal values such as those of formal unity and contrapuntal complexity.

Most likely, therefore, a more fitting way of pinning down these works is to link them to Franco Margola, a composer who is particularly dear to Fontanesi (who, it is perhaps worth remembering, curated the critical edition of Margola’s Quartet no. 7 for flute and strings). With Margola he shares the same desire to engage in a sort of neo-Baroquism purged of ideological pronouncements, whose apparent austerity is tempered by post-Romantic nostalgias and instances of subtle irony. But what they share to an even greater degree – over and above the obvious stylistic differences, given that Fontanesi lacks that modernist angularity (caused by the superimposition of different surfaces in a way reminiscent of synthetic cubism) that characterises Margola’s aesthetic approach ‒ is a specific idea of the composer’s craft. This ‒ to quote the words once used by the older master ‒ should be understood as a “silent craftsmanship that, in absolute modesty, operates in a way that is free of clamour and polemic”.

The general form of the works performed here, as has already been suggested, owes much to the format of the Baroque concerto, with a middle Andante movement placed between two Allegros. The formal concision we sometimes encounter does not prevent Fontanesi from presenting an abundant variety of melodic ideas, rhythmic inventions and unexpected modulations, though always within the bounds of an admirable structural clarity. Exemplary, in this sense, is the ‘Arcadian’ concerto for cello, with the solo instrument entrusted with the statement and development of a melodic line of great emotional vigour, that passes through various expressive landscapes as it follows the carefully planned key transitions from minor to major. The opening of the second movement, presented by the oboe and strings, transports us to an oneiric dimension, amplified by the songlike melodic phrases of the solo instrument. A refrain, which harks back to the main theme of the third movement of Khachaturian’s Cello Concerto (from the rhythmic point view and in its orchestration), sets the tempo of the final rondo, driving it through virtuosic cadenzas and orchestral crescendos to a finale of great intensity.

The Concerto for piano – called the ‘Frugal’, perhaps to underline its immediate appeal, in spite of a compositional style that is particularly refined and rich in interesting details (both formal and timbral) ‒ seems to bounce happily between the 19th and 20th centuries. For while the grandiose orchestral section and the virtuoso piano-playing displayed in the second movement hark back to late-romantic utterings, the radiance of the syncopated string and woodwind chords and the lively piano figurations that typify the brilliant outer movements transport us to the neoclassical world of the early 20th century, enriching the discourse with scintillating interactions between piano, percussion and (especially in the final movement) flute.

At times – it is the case, for example, in the first two movements of the Concerto for violin, called the ‘Elegiac’ – the composer embraces larger forms, which he exploits to develop to the utmost the broadly conceived themes played by the solo instrument, in a lively dialogue with the patterns of the accompanying orchestra; whereas in the final movement the violinist is called upon to answer, with flashes of virtuosity, the powerful orchestral chords that repeatedly affirm their presence.

Even longer is the first movement of the Flute concerto, which opens with an extended orchestral exposition, which is anything but merely introductory, given the wealth of thematic material and the contrapuntal density displayed. The entrance of the soloist is artfully delayed in the manner of the classical composers, who saw this as a particular source of pleasure for the audience. Yet listeners are here also provided with more sophisticated forms of gratification: like that of following the exposition and development of the various themes and participating in the close dialogue between soloist and orchestra. In this work, which the composer significantly labels as ‘Academic’, the classical style is also evoked in the measured emotional tone that pervades it, the admirable formal balance that sustains it, and the taut polyphonic strands that run through it. At the same time, however, the music allows itself pleasant distractions, particularly the melodies assigned to the flute, which are as relaxed and dreamlike in the second movement as they are swirling and vivacious in the rhythmically charged final movement.

Alongside the well-proportioned compositional framework, which conceals within it an abundance of syntactic nuances and shifting blends of timbre, what these four concertos have in common, from the emotional point of view, is the prevalence of idyllic and nostalgic tones that combine and alternate. In this way they project the mental image of an arcadia that is intangible, but ‒ as Friedrich Schiller had already theorised in his dissertation on the naïve and sentimental, towards the end of the 18th century ‒ still present, at least as an ideal goal, in our aspirations as inhabitants of modernity. Is this contemporary music? If one follows the commonly held opinion, that the contemporary must speak exclusively of present-day reality, and especially of its most decadent, degrading and dangerous facets ‒ a fashionable notion that has also taken root in the other art forms, and that insists, for example, that an artist should be classified as authentically “contemporary” only if his/her works duly express feelings such as unease, alienation and angst ‒ in that case the answer is no. But I believe it is high time to free ourselves of these stale clichés, in favour of an approach that may also capture the positive aspects of our being in the world and the gratifying experiences ‒ even through artistic (and specifically musical) creation ‒ that it can offer us. Among these, we should include the experience of listening to David Fontanesi’s concertos, which, with their refined outdatedness, are among the most genuine and seductive within the variegated panorama of contemporary music.

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads