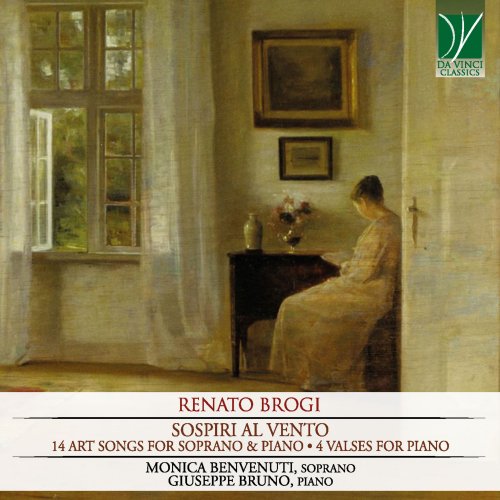

Monica Benvenuti, Giuseppe Bruno - Renato Brogi: Sospiri al vento (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Monica Benvenuti, Giuseppe Bruno

- Title: Renato Brogi: Sospiri al vento

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 00:57:38

- Total Size: 174 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

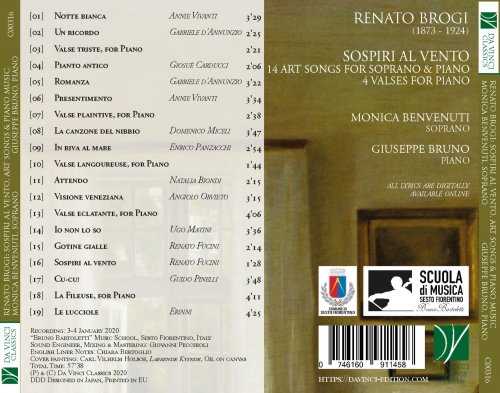

Tracklist

01. Notte bianca

02. Un ricordo

03. Valse triste (For Piano)

04. Pianto antico

05. Romanza

06. Presentimento

07. Valse plaintive (For Piano)

08. La canzone del nibbio

09. In riva al mare

10. Valse langoureuse (For Piano)

11. Attendo

12. Visione veneziana

13. Valse eclatante (For Piano)

14. Io non lo so

15. Gotine gialle

16. Sospiri al vento

17. Cu-cu

18. La Fileuse (For Piano)

19. Le lucciole

There are musical works which have the almost magical power of opening up a lost world in front of us. They may or may not be artistic masterpieces; but they undoubtedly fill our imagination with the aroma of another era, whose society, culture, art and sociability were very different from our own. This is the case with many of the works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album, entirely dedicated to the figure of Renato Brogi, an almost forgotten figure of musician whose relatively short life embraced the last quarter of the nineteenth century and the first of the twentieth.

Brogi came from a family of musicians. His father’s brother was Augusto Brogi, a well-known singer of his time, who performed as an acclaimed baritone on the most important Italian stages (from Rome to Milan, including the Teatro alla Scala, from Venice to Bologna) and who obtained great success also abroad, from Paris to Vienna, from Moscow to America, for example in Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro. After no less than fifteen years of successful career, Augusto was asked to sing the role of Jago in Verdi’s Otello; and – to his surprise as well as to the others’ – he discovered that he could sing even better as a tenor than as a baritone. He began then a second life as a tenor, where he was no less acclaimed than in the first.

With such an uncle, it is rather unsurprising that the child Renato was attracted by music, and particularly by singing. Indeed, Renato received his first music lessons precisely from Augusto, though Renato’s father, David, a shoemaker, was in turn an appreciated amateur singer. From the age of seven, Renato moved to Florence from his city of birth, Sesto Fiorentino; there, he studied piano with Ernesto Becucci at the Royal Conservatory of Music. Later still, he studied composition in Milan, under the guidance of two of the most appreciated pedagogues of the era, Michele Saladino and Vincenzo Ferroni, obtaining a second diploma. Brogi demonstrated his compositional skill with his diploma piece, a cantata for soloists, choir and orchestra by the title of Ermengarda.

In 1896, Brogi was awarded the first prize at the prestigious Steiner competition in Vienna with an opera, by the title of La prima notte, on a subject excerpted from one of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy-tales. The opera was performed in Florence two years later, and was warmly applauded. Following these important successes, Brogi wrote a second opera some years later (1904), whose title, Oblio (“oblivion”) in retrospect seems sadly to preconize its composer’s unjust fate. The forgetfulness in which Brogi slowly fell after his death could not be imagined at that time, however; in the same year of Oblio’s premiere, he won yet another composition contest with a Neapolitan song which became a great favourite of the era, Vienetenne.

It was however another character piece (a song for voice and piano in turn) which granted true fame to Brogi: it is Visione veneziana, one of the works recorded here, and which was interpreted and recorded by some of the greatest Italian singers of the twentieth century: from Cesare Siepi to Ettore Bastianini, from Titta Ruffo to Piero Cappuccilli, from Ruggero Raimondi to Giuseppe Di Stefano. (It will be noted that all of these singers are male, and most are baritones or basses: this Da Vinci Classics recording is unique in offering a rendition by a female voice). It is a haunting and lugubrious barcarolle, whose hypnotizing accompaniment evokes the gondola’s swaying on the Venetian lagoon: on the boat, covered in flowers, the corpse of a maiden is led to its resting place by her lover.

It is precisely in the field of chamber music for voice and piano that Brogi’s most authentic vein can be found; and this genre brought him national and international renown. His works attracted the attention of some of the leading singers of the era, and a few of these compositions continued to be found in the recital programmes of famous soloists throughout the first half of the twentiethcentury. The range of their dedicatees reveals the extended network of Brogi’s acquaintances and the artistry of the singers who appreciated his works: among them are Titta Ruffo, Gemma Bellincioni (who sang the leading role in Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana), but also the great pianist and composer Ferruccio Busoni.

After Oblio, Brogi did not return to operatic composition for another sixteen years; Isabella Orsini, staged exactly one century ago, in 1920, met with the approval of one of the most important Italian composers of the era, Ildebrando Pizzetti, who reviewed it very favourably. After being acclaimed in Florence and Rome, it was staged overseas, in the Brazilian cities of Rio de Janeiro and Saõ Paulo, and in Buenos Aires. Once more, the success of one opera led to further compositions for the stage; in 1923, Brogi tried his hand at operetta, with the extremely successful Bacco in Toscana, and immediately after he wrote Follie veneziane. Bacco in Toscana, in particular, appeared in the eyes of many as the perfect musical portrait of its composer: it is a sparkling and amiable work, featuring the typical Tuscan humour, sanguine and sometimes rustic, but frequently spicy and always pungent.

A contemporaneous critic defined Brogi as a “typical representative” of the rank and file of the “honest […] minor musicians”, whose popularity depended on his creation of good music for the pleasure of amateur musicians from the Tuscan upper classes. He was able to maintain a high compositional level throughout his career, which was abruptly ended by his premature death, at the unripe age of 51; he seemingly was somebody who knew well both the potential and limits of his talents, and who gave his best in the fields where his gifts could blossom. The same critic ventured a prophecy which would prove very accurate: in his view, Renato Brogi was “one of those musicians who, fifty or a hundred years after [their death], will be able to give, to their rediscoverers, the pleasure of the faded things, clouded over by time. Things which, however, still smell of a nostalgic scent, since they contain the most genuine and visible signs and characters of the musical habits of a given historical moment”.

The oblivion in which Brogi was destined to fall was possibly due also to a thorny political issue. The year of his death, 1924, was the second of the so-called “Fascist era”, and saw the cold-blooded assassination of the socialist leader Giacomo Matteotti by the Fascists; the regime was starting to display its ferocious and liberticide nature, and to establish its rhetoric as the official language of the Italian culture. Brogi was asked an expert’s evaluation on a seemingly minor matter, but which was deeply intertwined with this very rhetoric. It was maintained that Giovinezza, the official hymn of the Fascist regime, had been plagiarized by its supposed author from a children’s song written years earlier by another artist. This casual involvement in a burning political issue may have jeopardized Brogi’s possibility to be remembered at least on a par with his contemporaries Tosti and Denza.

The examples of his art recorded here demonstrate his versatile and multifaceted genius. His attention to the most important cultural trends of the era is revealed by his choice of the lyrics, some of which are written by the leading poets of the time (such as Gabriele d’Annunzio and Giosue Carducci), and of the poems themselves: two of them are, even nowadays, among the best known nineteenth-century poems, and were learned by heart by countless schoolchildren for decades (this is the case with Pianto antico, a touching poem on the death of Carducci’s only son). Many of the poems selected by Brogi for his songs offer to the musician a wide array of musical ideas: this happens, for example, with another extremely famous poem, La pioggia nel pineto, which is a masterful aural description of rainfall in a wood of pine-trees. On a lighter plane, aural phenomena evoked through onomatopoeias are found also in Cu-cu! on lyrics by Guido Pinelli; the baby-talk found here leads us to another world which seemingly fascinated Brogi deeply, i.e. that of childhood. Several of his songs give voice to motherly tenderness, to children’s games and nursery-rhymes; this may be due both to a particular vein by the composer, and to the tastes of his readership and audience. Brogi’s songs, in fact, were the perfect soundtrack for family life, for the free time and leisure of the educated bourgeois and aristocratic households. They were frequently sung and played by amateur musicians who sought pastimes, emotions and musical enjoyment in their artistic activities, and who found all of them abundantly in Brogi’s works.

While most of these pieces can be easily performed by dilettantes, only the accomplished artists can faithfully display the carefully nuanced palette of the sounds and styles invented by the composer; these beautiful musical miniatures require the most accurate rendition and delicate refinement in order to be appreciated for their full worth. The technical accomplishment needed for these expressive details is matched by the virtuosity found in one of the pieces for solo piano recorded here, La fileuse (the Spinner), which gives an Italian interpretation to a common topos of nineteenth-century descriptive music, but which requires a high level of mastery from the pianist due to its technical complexity.

This album, therefore, brings us a century back, and undoubtedly will give to its listeners the same musical pleasure experienced by their forebears who first listened to these pieces and sang them.

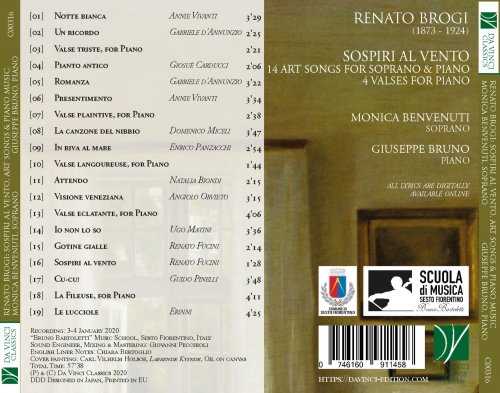

01. Notte bianca

02. Un ricordo

03. Valse triste (For Piano)

04. Pianto antico

05. Romanza

06. Presentimento

07. Valse plaintive (For Piano)

08. La canzone del nibbio

09. In riva al mare

10. Valse langoureuse (For Piano)

11. Attendo

12. Visione veneziana

13. Valse eclatante (For Piano)

14. Io non lo so

15. Gotine gialle

16. Sospiri al vento

17. Cu-cu

18. La Fileuse (For Piano)

19. Le lucciole

There are musical works which have the almost magical power of opening up a lost world in front of us. They may or may not be artistic masterpieces; but they undoubtedly fill our imagination with the aroma of another era, whose society, culture, art and sociability were very different from our own. This is the case with many of the works recorded in this Da Vinci Classics album, entirely dedicated to the figure of Renato Brogi, an almost forgotten figure of musician whose relatively short life embraced the last quarter of the nineteenth century and the first of the twentieth.

Brogi came from a family of musicians. His father’s brother was Augusto Brogi, a well-known singer of his time, who performed as an acclaimed baritone on the most important Italian stages (from Rome to Milan, including the Teatro alla Scala, from Venice to Bologna) and who obtained great success also abroad, from Paris to Vienna, from Moscow to America, for example in Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro. After no less than fifteen years of successful career, Augusto was asked to sing the role of Jago in Verdi’s Otello; and – to his surprise as well as to the others’ – he discovered that he could sing even better as a tenor than as a baritone. He began then a second life as a tenor, where he was no less acclaimed than in the first.

With such an uncle, it is rather unsurprising that the child Renato was attracted by music, and particularly by singing. Indeed, Renato received his first music lessons precisely from Augusto, though Renato’s father, David, a shoemaker, was in turn an appreciated amateur singer. From the age of seven, Renato moved to Florence from his city of birth, Sesto Fiorentino; there, he studied piano with Ernesto Becucci at the Royal Conservatory of Music. Later still, he studied composition in Milan, under the guidance of two of the most appreciated pedagogues of the era, Michele Saladino and Vincenzo Ferroni, obtaining a second diploma. Brogi demonstrated his compositional skill with his diploma piece, a cantata for soloists, choir and orchestra by the title of Ermengarda.

In 1896, Brogi was awarded the first prize at the prestigious Steiner competition in Vienna with an opera, by the title of La prima notte, on a subject excerpted from one of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy-tales. The opera was performed in Florence two years later, and was warmly applauded. Following these important successes, Brogi wrote a second opera some years later (1904), whose title, Oblio (“oblivion”) in retrospect seems sadly to preconize its composer’s unjust fate. The forgetfulness in which Brogi slowly fell after his death could not be imagined at that time, however; in the same year of Oblio’s premiere, he won yet another composition contest with a Neapolitan song which became a great favourite of the era, Vienetenne.

It was however another character piece (a song for voice and piano in turn) which granted true fame to Brogi: it is Visione veneziana, one of the works recorded here, and which was interpreted and recorded by some of the greatest Italian singers of the twentieth century: from Cesare Siepi to Ettore Bastianini, from Titta Ruffo to Piero Cappuccilli, from Ruggero Raimondi to Giuseppe Di Stefano. (It will be noted that all of these singers are male, and most are baritones or basses: this Da Vinci Classics recording is unique in offering a rendition by a female voice). It is a haunting and lugubrious barcarolle, whose hypnotizing accompaniment evokes the gondola’s swaying on the Venetian lagoon: on the boat, covered in flowers, the corpse of a maiden is led to its resting place by her lover.

It is precisely in the field of chamber music for voice and piano that Brogi’s most authentic vein can be found; and this genre brought him national and international renown. His works attracted the attention of some of the leading singers of the era, and a few of these compositions continued to be found in the recital programmes of famous soloists throughout the first half of the twentiethcentury. The range of their dedicatees reveals the extended network of Brogi’s acquaintances and the artistry of the singers who appreciated his works: among them are Titta Ruffo, Gemma Bellincioni (who sang the leading role in Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana), but also the great pianist and composer Ferruccio Busoni.

After Oblio, Brogi did not return to operatic composition for another sixteen years; Isabella Orsini, staged exactly one century ago, in 1920, met with the approval of one of the most important Italian composers of the era, Ildebrando Pizzetti, who reviewed it very favourably. After being acclaimed in Florence and Rome, it was staged overseas, in the Brazilian cities of Rio de Janeiro and Saõ Paulo, and in Buenos Aires. Once more, the success of one opera led to further compositions for the stage; in 1923, Brogi tried his hand at operetta, with the extremely successful Bacco in Toscana, and immediately after he wrote Follie veneziane. Bacco in Toscana, in particular, appeared in the eyes of many as the perfect musical portrait of its composer: it is a sparkling and amiable work, featuring the typical Tuscan humour, sanguine and sometimes rustic, but frequently spicy and always pungent.

A contemporaneous critic defined Brogi as a “typical representative” of the rank and file of the “honest […] minor musicians”, whose popularity depended on his creation of good music for the pleasure of amateur musicians from the Tuscan upper classes. He was able to maintain a high compositional level throughout his career, which was abruptly ended by his premature death, at the unripe age of 51; he seemingly was somebody who knew well both the potential and limits of his talents, and who gave his best in the fields where his gifts could blossom. The same critic ventured a prophecy which would prove very accurate: in his view, Renato Brogi was “one of those musicians who, fifty or a hundred years after [their death], will be able to give, to their rediscoverers, the pleasure of the faded things, clouded over by time. Things which, however, still smell of a nostalgic scent, since they contain the most genuine and visible signs and characters of the musical habits of a given historical moment”.

The oblivion in which Brogi was destined to fall was possibly due also to a thorny political issue. The year of his death, 1924, was the second of the so-called “Fascist era”, and saw the cold-blooded assassination of the socialist leader Giacomo Matteotti by the Fascists; the regime was starting to display its ferocious and liberticide nature, and to establish its rhetoric as the official language of the Italian culture. Brogi was asked an expert’s evaluation on a seemingly minor matter, but which was deeply intertwined with this very rhetoric. It was maintained that Giovinezza, the official hymn of the Fascist regime, had been plagiarized by its supposed author from a children’s song written years earlier by another artist. This casual involvement in a burning political issue may have jeopardized Brogi’s possibility to be remembered at least on a par with his contemporaries Tosti and Denza.

The examples of his art recorded here demonstrate his versatile and multifaceted genius. His attention to the most important cultural trends of the era is revealed by his choice of the lyrics, some of which are written by the leading poets of the time (such as Gabriele d’Annunzio and Giosue Carducci), and of the poems themselves: two of them are, even nowadays, among the best known nineteenth-century poems, and were learned by heart by countless schoolchildren for decades (this is the case with Pianto antico, a touching poem on the death of Carducci’s only son). Many of the poems selected by Brogi for his songs offer to the musician a wide array of musical ideas: this happens, for example, with another extremely famous poem, La pioggia nel pineto, which is a masterful aural description of rainfall in a wood of pine-trees. On a lighter plane, aural phenomena evoked through onomatopoeias are found also in Cu-cu! on lyrics by Guido Pinelli; the baby-talk found here leads us to another world which seemingly fascinated Brogi deeply, i.e. that of childhood. Several of his songs give voice to motherly tenderness, to children’s games and nursery-rhymes; this may be due both to a particular vein by the composer, and to the tastes of his readership and audience. Brogi’s songs, in fact, were the perfect soundtrack for family life, for the free time and leisure of the educated bourgeois and aristocratic households. They were frequently sung and played by amateur musicians who sought pastimes, emotions and musical enjoyment in their artistic activities, and who found all of them abundantly in Brogi’s works.

While most of these pieces can be easily performed by dilettantes, only the accomplished artists can faithfully display the carefully nuanced palette of the sounds and styles invented by the composer; these beautiful musical miniatures require the most accurate rendition and delicate refinement in order to be appreciated for their full worth. The technical accomplishment needed for these expressive details is matched by the virtuosity found in one of the pieces for solo piano recorded here, La fileuse (the Spinner), which gives an Italian interpretation to a common topos of nineteenth-century descriptive music, but which requires a high level of mastery from the pianist due to its technical complexity.

This album, therefore, brings us a century back, and undoubtedly will give to its listeners the same musical pleasure experienced by their forebears who first listened to these pieces and sang them.

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads