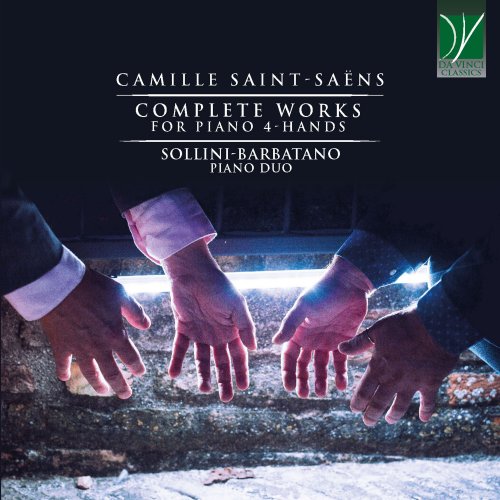

Marco Sollini, Salvatore Barbatano - Camille Saint-Saëns: Complete Works for Piano 4-Hands (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Marco Sollini, Salvatore Barbatano

- Title: Camille Saint-Saëns: Complete Works for Piano 4-Hands

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 1:01:03

- Total Size: 255 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Duettino in G Major, Op. 11

02. Variations on a Theme of Beethoven in E-Flat Major, Op. 35

03. Danse macabre. Poème symphonique, Op. 40 (Arrangé par Ernest Guiraud)

04. König Harald Harfagar, Op. 59

05. Feuillet d'Album in B-Flat Major, Op. 81

06. Pas redoublé in B-Flat Major, Op. 86

07. Berceuse, Op. 105

08. Marche interalliée, Op. 155

09. Le Carnaval des Animaux, R.125: XIII. Le Cygne (Arrangé par Jacques Durand)

01. Duettino in G Major, Op. 11

02. Variations on a Theme of Beethoven in E-Flat Major, Op. 35

03. Danse macabre. Poème symphonique, Op. 40 (Arrangé par Ernest Guiraud)

04. König Harald Harfagar, Op. 59

05. Feuillet d'Album in B-Flat Major, Op. 81

06. Pas redoublé in B-Flat Major, Op. 86

07. Berceuse, Op. 105

08. Marche interalliée, Op. 155

09. Le Carnaval des Animaux, R.125: XIII. Le Cygne (Arrangé par Jacques Durand)

The four-hand piano duet is a chamber music ensemble with rather unique qualities. By allowing twenty fingers to play on the piano keyboard’s eighty-eight keys, it responds to two entirely contrasting needs. From the one side, the two players may divide among themselves a certain number of notes: this is a welcome opportunity for amateur players, whose limited pianistic skills prevent them from playing difficult pieces. By sharing the burden of a more complex performance with a fellow pianist, amateurs can produce aurally satisfactory performances even without being great solo virtuosos. However, and from the other side, a piano duet may also multiply the notes. In this case, each one of the two pianists will be a virtuoso in his or her own right, and the sum total of the notes they can play together will abundantly exceed those playable by a single musician, however talented. When employed in this fashion, the piano duet may become the epitome of pianistic virtuosity, both because of the technical accomplishment it requires of the players, and due to the impressive aural result it may achieve.

The works for piano duet composed by Camille Saint-Saëns respond to both needs, and this variety is fascinatingly exemplified in this Da Vinci Classics album.

Saint-Saëns is regarded as one of the greatest French composers who lived between nineteenth and twentieth century, although his works still await the recognition they deserve. Whilst Saint-Saëns’ standing as an absolute master of composition is not debated, his music seems to challenge the usual labels: he was not an Impressionist, he was not a Romantic, but he was also not really a Classicist (it would be difficult to describe his Samson et Dalila as a Classicist work!). He had a sense of humour, he liked instrumental virtuosity, and had plenty of musical ideas which he knew how to thoroughly develop.

Saint-Saëns had been an exceptional child prodigy, showing unmistakable signs of musical genius at the age of three, and going on as an extraordinarily precocious piano virtuoso. His pianistic proficiency is clearly mirrored by the most brilliant of the pieces for four-hand piano duet recorded here. However, he was also an organ virtuoso, and it was indeed as a church organist that he earned his living for many years. From the organ balcony, he used to delight his listeners with breath-taking improvisations, mirroring his fecund musical imagination, but also (in some cases) ending up as new themes or musical ideas for his written compositions. He taught piano only for a short time, but left a trace due to his open-mindedness and to his inclination toward contemporaneous music. He was a polymath, who authored scientific essays in a number of fields, but he also wrote poetry and plays, as well as popular books issued under a pen name.

He was both popular and unpopular, and this division between admirers and censors lasts until present day. Some of his works rank among the best-known pieces in the entire classical music repertoire (ironically, one of these is Le carnaval des animaux, of which he had forbidden the publication), and, during his lifetime, he enjoyed an immense renown. He was admired and praised by Franz Liszt, who ranked him among the two top pianists of the era (the other, of course, was Liszt himself). On the other hand, a large portion of his output still awaits rediscovery, and this is one of the reasons why this Da Vinci Classics album is particularly welcome.

In this recording, both Saint-Saëns’ genius and the reasons for its limited appreciation can be observed. Along with absolute masterpieces, there are other works which in fact are little masterpieces in their own genre, but fall abundantly short with respect to the “seriousness” one normally associates with the great repertoire of classical music. Of course, these standards are entirely artificial, and a tragic mood is not a required quality for a musical masterpiece. Indeed, being able to create beautiful works out of occasional pieces, or of pieces written for the amusement of the music lovers is the mark of a true and real genius.

For example, the Duettino op. 11 unmistakably belongs in the ranks of amateur music, and immediately suggests, upon hearing, the bourgeois salons of the nineteenth century. Written by a twenty-years-old composer, but unpublished until 1863 and not premiered until 1868, it brings to our eyes the images of the mid-century cultivated class. Its two sections, both in G major, are contrasting in mood. The piece opens with a calm and cantabile tune with elegant variations, whilst the second part is a quick perpetuum mobile with a continuous and flowing movement of semiquavers. Saint-Saëns’ mastery of the “effectful” writing is also displayed by the occasional heroic moments, and by his capability to craft a piece with a perfect balance of all the needed ingredients.

The Variations sur un thême de Beethoven op. 35 were written in 1874, and therefore postdate the Duettino by nearly two decades. Saint-Saëns was a great admirer of Beethoven’s music, but in this case he turned his attention to the ironic and mischievous side of the German genius’ music. When thinking of Beethoven, in fact, most people conjure the image of a perpetually frowning man. Of course, many of Beethoven’s masterpieces are marked by a deeply tragical vein, and his pessimism is abundantly justified by the circumstances of his life and illness. Still, Beethoven was also more than capable of smiling, of joking (and also of hoping and of praying, as could be the case). In his Sonatas op. 31, several moments of pure joy, and sometimes of good-humoured irony are found, and it is one of these that inspired Saint-Saëns. Beethoven’s theme is found in the Trio from the Minuet (third movement) of his Sonata op. 31 no. 3. Saint-Saëns adorns it with eight variations with an added fugue, clearly reminiscent of Beethoven’s own variation cycles. The potential for a dialogic writing was already embedded in Beethoven’s original, and Saint-Saëns’ scoring for piano duet brings it to light in a very impressive fashion. Saint-Saëns’ variation cycles explored a wide palette of musical and technical effects, considering many possibilities in terms of compositional devices and of pianistic solutions. The result is a magnificent composition, which places high requirements on the players as concerns both their musicianship and their technique.

One should not forget, in fact, that Saint-Saëns remained a great piano virtuoso throughout his life, and that he also liked to engage with his friends and colleagues in musical “duels” aiming at demonstrating the contenders’ musical imagination and pianistic technique at the same time. These Variations almost seem to stem from one such occasion.

The Danse macabre op. 40 ranks among Saint-Saëns’ most famous and celebrated works, to the point that he himself would cite it (with some self-irony) in the Carnaval des animaux. It was conceived at first as a chanson, set to lyrics written by a physician, Henri Cazalis. The composer later orchestrated it with hypnotic and unheard-of solutions. It met with a very mixed reception: the xylophone had not been previously employed in classical music and in an orchestral piece, and the screeching solo violin or the parody of the sacred tune of the Dies irae disconcerted many listeners. In spite of this, the work quickly conquered its (large) audience, and the composer realized a brilliant version for two pianos. It was the famous arranger Ernest Guiraud who created the transcription for four-hand piano duet performed here, probably taking as his point of departure the orchestral (rather than the two-piano) version.

By way of contrast, König Harald Harfargar op. 59 is one of the least known among Saint-Saëns works. Harald “Fair Hair” (this is how Harfargar is translated) is a mythical (but also historical) figure of Norway. He lived in the tenth century, and is credited with the unification of the entire Norwegian country. Therefore, he is also the symbolic patron of his land, and has been celebrated in poetry and tales. One such example is the poem by Heinrich Heine to which Saint-Saëns alluded in his composition. According to Heine’s imagery, the King “sits in the depths below”, where he admires a beautiful Water Fairy. His contemplation can only be interrupted if his beloved country is in need, in which case he will rise to defend it.

The remaining pieces of the Album are, as previously stated, beautiful examples of Saint-Saëns’ capability to create little masterpieces out of occasional pieces. For example, the small, unpretentious Feuillet d’album op. 81 is as diminutive as its name, but, at the same time, it displays the composer’s mastery in the elaborated polyphony of its central part. The Pas redoublé op. 86 and the Marche interalliée op. 155 are inspired by the military world. The former is a “quickstep” concert march, in which the march’s usual pace is doubled (hence the name) so as to become a charge; its three themes are separated by interludes, and the result is both pleasant and inspiring. The Marche interalliée had been commissioned to him by Admiral Ernest Fournier, who presided the “Cercle Interallié”, the Club of the Inter-Allies, as one might translate its name. As Saint-Saëns wrote to his publisher, the Admiral’s invitation was “impossible to refuse”. He planned to write a “monster-piece”, whose orchestration he entrusted to Guillaume Balay, the music director of the Republican Guard, and later he re-transcribed it for piano duet.

A completely different mood is found in the two remaining pieces. The Berceuse op. 105 is delicate, refined, purposefully naïve; perhaps, Saint-Saëns was thinking of his two children, who died within the space of less than two months, in 1878. Little needs to be written about Le Cygne, probably Saint-Saëns’ best-known tune, and the only movement of Le Carnaval des animaux whose publication he authorised. Still, in spite of its immense celebrity, this piece never ceases to enchant, to enthrall and to touch its listeners; it is the demonstration that a famous work can also be a real, fully-fledged, masterpiece.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2021

The works for piano duet composed by Camille Saint-Saëns respond to both needs, and this variety is fascinatingly exemplified in this Da Vinci Classics album.

Saint-Saëns is regarded as one of the greatest French composers who lived between nineteenth and twentieth century, although his works still await the recognition they deserve. Whilst Saint-Saëns’ standing as an absolute master of composition is not debated, his music seems to challenge the usual labels: he was not an Impressionist, he was not a Romantic, but he was also not really a Classicist (it would be difficult to describe his Samson et Dalila as a Classicist work!). He had a sense of humour, he liked instrumental virtuosity, and had plenty of musical ideas which he knew how to thoroughly develop.

Saint-Saëns had been an exceptional child prodigy, showing unmistakable signs of musical genius at the age of three, and going on as an extraordinarily precocious piano virtuoso. His pianistic proficiency is clearly mirrored by the most brilliant of the pieces for four-hand piano duet recorded here. However, he was also an organ virtuoso, and it was indeed as a church organist that he earned his living for many years. From the organ balcony, he used to delight his listeners with breath-taking improvisations, mirroring his fecund musical imagination, but also (in some cases) ending up as new themes or musical ideas for his written compositions. He taught piano only for a short time, but left a trace due to his open-mindedness and to his inclination toward contemporaneous music. He was a polymath, who authored scientific essays in a number of fields, but he also wrote poetry and plays, as well as popular books issued under a pen name.

He was both popular and unpopular, and this division between admirers and censors lasts until present day. Some of his works rank among the best-known pieces in the entire classical music repertoire (ironically, one of these is Le carnaval des animaux, of which he had forbidden the publication), and, during his lifetime, he enjoyed an immense renown. He was admired and praised by Franz Liszt, who ranked him among the two top pianists of the era (the other, of course, was Liszt himself). On the other hand, a large portion of his output still awaits rediscovery, and this is one of the reasons why this Da Vinci Classics album is particularly welcome.

In this recording, both Saint-Saëns’ genius and the reasons for its limited appreciation can be observed. Along with absolute masterpieces, there are other works which in fact are little masterpieces in their own genre, but fall abundantly short with respect to the “seriousness” one normally associates with the great repertoire of classical music. Of course, these standards are entirely artificial, and a tragic mood is not a required quality for a musical masterpiece. Indeed, being able to create beautiful works out of occasional pieces, or of pieces written for the amusement of the music lovers is the mark of a true and real genius.

For example, the Duettino op. 11 unmistakably belongs in the ranks of amateur music, and immediately suggests, upon hearing, the bourgeois salons of the nineteenth century. Written by a twenty-years-old composer, but unpublished until 1863 and not premiered until 1868, it brings to our eyes the images of the mid-century cultivated class. Its two sections, both in G major, are contrasting in mood. The piece opens with a calm and cantabile tune with elegant variations, whilst the second part is a quick perpetuum mobile with a continuous and flowing movement of semiquavers. Saint-Saëns’ mastery of the “effectful” writing is also displayed by the occasional heroic moments, and by his capability to craft a piece with a perfect balance of all the needed ingredients.

The Variations sur un thême de Beethoven op. 35 were written in 1874, and therefore postdate the Duettino by nearly two decades. Saint-Saëns was a great admirer of Beethoven’s music, but in this case he turned his attention to the ironic and mischievous side of the German genius’ music. When thinking of Beethoven, in fact, most people conjure the image of a perpetually frowning man. Of course, many of Beethoven’s masterpieces are marked by a deeply tragical vein, and his pessimism is abundantly justified by the circumstances of his life and illness. Still, Beethoven was also more than capable of smiling, of joking (and also of hoping and of praying, as could be the case). In his Sonatas op. 31, several moments of pure joy, and sometimes of good-humoured irony are found, and it is one of these that inspired Saint-Saëns. Beethoven’s theme is found in the Trio from the Minuet (third movement) of his Sonata op. 31 no. 3. Saint-Saëns adorns it with eight variations with an added fugue, clearly reminiscent of Beethoven’s own variation cycles. The potential for a dialogic writing was already embedded in Beethoven’s original, and Saint-Saëns’ scoring for piano duet brings it to light in a very impressive fashion. Saint-Saëns’ variation cycles explored a wide palette of musical and technical effects, considering many possibilities in terms of compositional devices and of pianistic solutions. The result is a magnificent composition, which places high requirements on the players as concerns both their musicianship and their technique.

One should not forget, in fact, that Saint-Saëns remained a great piano virtuoso throughout his life, and that he also liked to engage with his friends and colleagues in musical “duels” aiming at demonstrating the contenders’ musical imagination and pianistic technique at the same time. These Variations almost seem to stem from one such occasion.

The Danse macabre op. 40 ranks among Saint-Saëns’ most famous and celebrated works, to the point that he himself would cite it (with some self-irony) in the Carnaval des animaux. It was conceived at first as a chanson, set to lyrics written by a physician, Henri Cazalis. The composer later orchestrated it with hypnotic and unheard-of solutions. It met with a very mixed reception: the xylophone had not been previously employed in classical music and in an orchestral piece, and the screeching solo violin or the parody of the sacred tune of the Dies irae disconcerted many listeners. In spite of this, the work quickly conquered its (large) audience, and the composer realized a brilliant version for two pianos. It was the famous arranger Ernest Guiraud who created the transcription for four-hand piano duet performed here, probably taking as his point of departure the orchestral (rather than the two-piano) version.

By way of contrast, König Harald Harfargar op. 59 is one of the least known among Saint-Saëns works. Harald “Fair Hair” (this is how Harfargar is translated) is a mythical (but also historical) figure of Norway. He lived in the tenth century, and is credited with the unification of the entire Norwegian country. Therefore, he is also the symbolic patron of his land, and has been celebrated in poetry and tales. One such example is the poem by Heinrich Heine to which Saint-Saëns alluded in his composition. According to Heine’s imagery, the King “sits in the depths below”, where he admires a beautiful Water Fairy. His contemplation can only be interrupted if his beloved country is in need, in which case he will rise to defend it.

The remaining pieces of the Album are, as previously stated, beautiful examples of Saint-Saëns’ capability to create little masterpieces out of occasional pieces. For example, the small, unpretentious Feuillet d’album op. 81 is as diminutive as its name, but, at the same time, it displays the composer’s mastery in the elaborated polyphony of its central part. The Pas redoublé op. 86 and the Marche interalliée op. 155 are inspired by the military world. The former is a “quickstep” concert march, in which the march’s usual pace is doubled (hence the name) so as to become a charge; its three themes are separated by interludes, and the result is both pleasant and inspiring. The Marche interalliée had been commissioned to him by Admiral Ernest Fournier, who presided the “Cercle Interallié”, the Club of the Inter-Allies, as one might translate its name. As Saint-Saëns wrote to his publisher, the Admiral’s invitation was “impossible to refuse”. He planned to write a “monster-piece”, whose orchestration he entrusted to Guillaume Balay, the music director of the Republican Guard, and later he re-transcribed it for piano duet.

A completely different mood is found in the two remaining pieces. The Berceuse op. 105 is delicate, refined, purposefully naïve; perhaps, Saint-Saëns was thinking of his two children, who died within the space of less than two months, in 1878. Little needs to be written about Le Cygne, probably Saint-Saëns’ best-known tune, and the only movement of Le Carnaval des animaux whose publication he authorised. Still, in spite of its immense celebrity, this piece never ceases to enchant, to enthrall and to touch its listeners; it is the demonstration that a famous work can also be a real, fully-fledged, masterpiece.

Chiara Bertoglio © 2021

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

Facebook

Twitter

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads