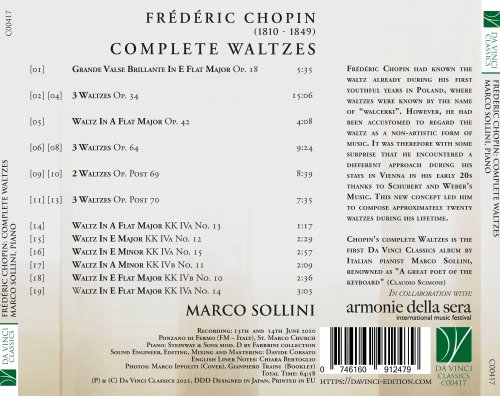

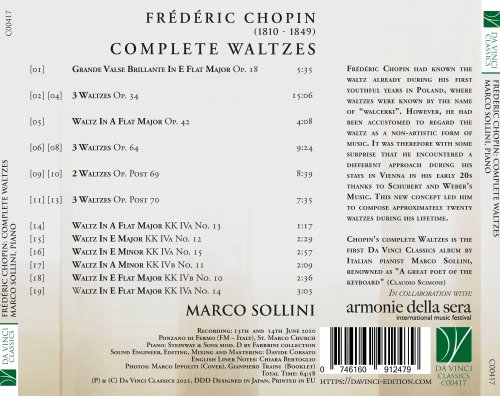

Marco Sollini - Frédéric Chopin: Complete Waltzes (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Marco Sollini

- Title: Frédéric Chopin: Complete Waltzes

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical Piano

- Quality: flac lossless

- Total Time: 01:04:58

- Total Size: 235 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist

01. Grande valse brillante in E-Flat Major, Op. 18

02. Waltzes, Op. 34: No. 1 in A-Flat Major, Vivace

03. Waltzes, Op. 34: No. 2 in E Minor, Lento

04. Waltzes, Op. 34: No. 3 in F Major, Vivace

05. Waltz in A-Flat Major, Op. 42

06. Waltzes, Op. 64: No. 1 in D-Flat Major, Molto vivace

07. Waltzes, Op. 64: No. 2 in C-Sharp Minor, Tempo giusto

08. Waltzes, Op. 64: No. 3 in A-Flat Major, Moderato

09. Waltzes, Op. 69 posth.: No. 1 in A-Flat Major, Lento

10. Waltzes, Op. 69 posth.: No. 2 in B Minor, Moderato

11. Waltzes, Op. 70 posth.: No. 1 in G-Flat Major, Molto vivace

12. Waltzes, Op. 70 posth.: No. 2 in F Minor, Tempo giusto

13. Waltzes, Op. 70 posth.: No. 3 in D-Flat Major, Moderato

14. Waltz in A-Flat Major, B. 21

15. Waltz in E Major, B. 44

16. Waltz in E Minor, B. 56

17. Waltz in A Minor, B. 51

18. Waltz in E-Flat Major, B. 37

19. Waltz in E-Flat Major, B. 46

When discussing works of “pure” instrumental music or vocal works (even in the sacred repertoire), it is something of a musicological commonplace to find a “dancing” character in pieces written in triple time. Undeniably, even in works which could not be farther from the dancing hall (such as some arias in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion), the presence of a 3/4 or 3/8 time unavoidably suggests an association with dancing, and this probably was purposefully willed by the composer. This may seem puzzling at first: there are plenty of dances written in 2 or in 4, and, of course, not all pieces in triple time have recognizable connections with dancing patterns. However, ternary rhythms seem powerfully to evoke graceful movements, and our bodies frequently tend to spontaneously accompany musical works in triple time with slight gestures, almost unconsciously.

The reason for this may be almost philosophical: whereas our walking “rhythm” is normally in duple time, the presence of a third beat suggests a space of superabundance, of freedom, of “grace”: something unusual, something unbound by necessity or compulsion, something free from the daily activities (such as walking), a space of “graced” time, available for loving, for enjoying life, for art. The third step, or the third beat, is the locus where our humanity may flourish, unconstrained by what “has to be done”: it is an opportunity to “play”, to act out of sheer free will, to move for movement’s sake and out of an outflowing availability of life, energy and joy.

The history of Western music is populated by a number of dances in triple-time; some of them have become true icons of their times, both culturally and musically. Among the best known is certainly the Minuet, which flourished in the Baroque and Classical era, embodying the refined elegance of the aristocratic courts. The Baroque era also saw the phenomenon of originally frantic dances in triple time, such as the Sarabande or Passacaille, which later became very solemn, composed and hieratic dance forms within the Baroque Suite. In the Classical era, the Ländler began to establish itself as a favourite dance. As many other dances, it had popular origins; it was born in the countryside, where it was danced in open spaces by peasants wearing heavy wooden clogs. While these probably prevented the dancers’ stepping on their partners’ toes – a typical inconvenient when dancing with beginners! – of course this gear did not permit agility and quick movements. These features are reflected in the “artistic” Ländler composed by the great masters of the first Viennese school, such as Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert.

When the Ländler moved from the farmyard to the ballroom, and when the dancing couples started to come from the bourgeois and aristocratic classes, the Ländler quickly gave way to its more elegant, swift and exciting cousin, the waltz.

By the first decades of the nineteenth century, the waltz had become the fad of the day. The etymology of its name comes from the German verb waltzen, meaning “to roll”; of course, this refers to the whirling movements performed by the dancing couples. The waltz was as disapproved by the moralists (and also by someone which can hardly be regarded as a moralist, i.e. Lord Byron) as it was loved by the young. In fact, within a social context in which physical intimacy was rigidly restricted, and the opportunities to spend time in close proximity with members of the opposite sex were rare, the waltz provided a welcome possibility for dancing in a tight embrace and for looking one’s partner in the eyes. This was not only an expression of tenderness, but also a need: as everyone who has danced a waltz knows well, unless the dancers fix their gaze into their partner’s eyes, the spinning movement becomes hard to sustain and may give headache or dizziness. For this reason, and also for the exhaustion it caused with its speed, waltzing was discouraged also by some physicians – while, actually, it was highly beneficial as an entertaining form of gymnastics.

Of course Frédéric Chopin had known the waltz already during his first youthful years in Poland, where waltzes were known by the name of “walcerki”. However, he had been accustomed to regard the waltz as a non-artistic form of music; as consumer music, in modern terms. It was simply the background of a social activity, and its music was little more than a series of aural “signs” for the dancers: the triple time marked the steps, and the purposefully and clearly foreseeable harmonic turns indicated the changing figurations of the dance.

It was therefore with some surprise that Chopin encountered a different approach during his stays in Vienna in his early 20s. As he wrote to his former teacher in Warsaw, Józef Franciszek Eisner (1769-1854), “Waltzes are regarded as works here!”. Chopin’s somewhat obscure expression manifests the young musician’s amazement at the fact that a genre he regarded as merely functional could be considered as a work of art. Doubtlessly, the elevation of the waltz to “music” (and to a kind of music which did not necessarily need the physical gestures of dancing in order to be tolerated…) was also due to the beautiful miniature waltzes written by Franz Schubert (published in 1821 and 1830), along with the increasing popularity of the waltzes by Lanner or Johann Strauss senior. Moreover, in 1819 Carl Maria von Weber’s Invitation to the Dance was published, and it proposed an alternative view on the waltz: here, a series of short waltzes was presented as a suite, interspersed with virtuoso and brilliant moments, but also offering an expressive place for lyricism, tenderness and poetry.

It was this concept of waltz which ultimately appealed to Chopin, and led him to compose approximately twenty waltzes during his lifetime. The uncertainty as to the precise number is due to the fact that there are a few known works whose authorship is disputed; another (KK IVb No. 10, “Sostenuto”) is certainly by Chopin, but which bears no title, and therefore may be classified under other rubrics (such as Mazurka or Nocturne); and others whose manuscripts are unavailable (but known to have survived). While Chopin was generally rather selective in the choice of which of his works to publish, the case of his waltzes is unique even by his standards. Only eight of his waltzes were published during his lifetime; others were printed posthumously (but with an opus number) thanks to the efforts of Julian Fontana and of Chopin’s sister; still others were published at a later date and without opus number. Moreover, even in the case of the pieces printed during Chopin’s lifetime, their opus numbers do not correspond to their composition date, and are therefore rather misleading. The two waltzes of op. 69, for example, date respectively from 1835 and 1829; the three pieces of op. 70 cover a time span of no less than thirteen years, having been composed respectively in 1832, 1842 and 1829.

Paradoxically, sometimes it is easier to establish an authoritative version for the unpublished waltzes than for those published during Chopin’s lifetime. In fact, the published waltzes were obviously representative of his most popular works. Therefore, not only there was the printed version, but also a number of manuscript copies, frequently holographs of the composer, which he used to present as gifts or homages to his pupils, friends, acquaintances or lovers. Each of these autographs mirrors a different version of the piece; sometimes, the variants are minimal, but in other cases they involve substantial aspects of the piece’s shape. This should not be seen as a flaw: rather, it reveals a flexible concept of work (almost an “open work”, as we would say in today’s terms), which could also be tailored to the receiver’s taste or ability.

In general, Chopin’s waltzes were not conceived as pieces to accompany dancing proper, although most of them have later been employed as ballet music or as accompaniments to other dance-like activities (such as ice skating or rhythmic gymnastics). Therefore, they can display a much richer harmonic structure, more flexible rhythmic patterns (in which, paradoxically, frequently the underlying triple time conflicts with tunes with a binary subdivision), and a virtuoso component which attracts the listener’s attention on the pianist’s brilliancy and mastery of the keyboard. The lyrical element is also frequently found, as, for example, in one of the best known pieces in Chopin’s oeuvre, i.e. the beautiful Waltz op. 64 no. 2. The lighthearted aspect of some of them (such as, for example, the so-called “Minute-Waltz”) contrasts with the melancholy found in some others; still others have virtuosity as their keystone, such as in the case of the Grande Valse Brillante op. 18 and of the other works to which the adjective “brillante” has been added.

Chopin continued composing Waltzes until the very last years of his life, and the works he composed in his final years display an extraordinary harmonic complexity, typical of his late style. With him, the waltz acquired the status of masterpiece, and it became able to convey a large variety of emotional states. This is ironic, if one considers how he had doubted the fact that waltzes could be “works”: indeed, he managed to conquer for them pride of place in the piano repertoire of all times.

01. Grande valse brillante in E-Flat Major, Op. 18

02. Waltzes, Op. 34: No. 1 in A-Flat Major, Vivace

03. Waltzes, Op. 34: No. 2 in E Minor, Lento

04. Waltzes, Op. 34: No. 3 in F Major, Vivace

05. Waltz in A-Flat Major, Op. 42

06. Waltzes, Op. 64: No. 1 in D-Flat Major, Molto vivace

07. Waltzes, Op. 64: No. 2 in C-Sharp Minor, Tempo giusto

08. Waltzes, Op. 64: No. 3 in A-Flat Major, Moderato

09. Waltzes, Op. 69 posth.: No. 1 in A-Flat Major, Lento

10. Waltzes, Op. 69 posth.: No. 2 in B Minor, Moderato

11. Waltzes, Op. 70 posth.: No. 1 in G-Flat Major, Molto vivace

12. Waltzes, Op. 70 posth.: No. 2 in F Minor, Tempo giusto

13. Waltzes, Op. 70 posth.: No. 3 in D-Flat Major, Moderato

14. Waltz in A-Flat Major, B. 21

15. Waltz in E Major, B. 44

16. Waltz in E Minor, B. 56

17. Waltz in A Minor, B. 51

18. Waltz in E-Flat Major, B. 37

19. Waltz in E-Flat Major, B. 46

When discussing works of “pure” instrumental music or vocal works (even in the sacred repertoire), it is something of a musicological commonplace to find a “dancing” character in pieces written in triple time. Undeniably, even in works which could not be farther from the dancing hall (such as some arias in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion), the presence of a 3/4 or 3/8 time unavoidably suggests an association with dancing, and this probably was purposefully willed by the composer. This may seem puzzling at first: there are plenty of dances written in 2 or in 4, and, of course, not all pieces in triple time have recognizable connections with dancing patterns. However, ternary rhythms seem powerfully to evoke graceful movements, and our bodies frequently tend to spontaneously accompany musical works in triple time with slight gestures, almost unconsciously.

The reason for this may be almost philosophical: whereas our walking “rhythm” is normally in duple time, the presence of a third beat suggests a space of superabundance, of freedom, of “grace”: something unusual, something unbound by necessity or compulsion, something free from the daily activities (such as walking), a space of “graced” time, available for loving, for enjoying life, for art. The third step, or the third beat, is the locus where our humanity may flourish, unconstrained by what “has to be done”: it is an opportunity to “play”, to act out of sheer free will, to move for movement’s sake and out of an outflowing availability of life, energy and joy.

The history of Western music is populated by a number of dances in triple-time; some of them have become true icons of their times, both culturally and musically. Among the best known is certainly the Minuet, which flourished in the Baroque and Classical era, embodying the refined elegance of the aristocratic courts. The Baroque era also saw the phenomenon of originally frantic dances in triple time, such as the Sarabande or Passacaille, which later became very solemn, composed and hieratic dance forms within the Baroque Suite. In the Classical era, the Ländler began to establish itself as a favourite dance. As many other dances, it had popular origins; it was born in the countryside, where it was danced in open spaces by peasants wearing heavy wooden clogs. While these probably prevented the dancers’ stepping on their partners’ toes – a typical inconvenient when dancing with beginners! – of course this gear did not permit agility and quick movements. These features are reflected in the “artistic” Ländler composed by the great masters of the first Viennese school, such as Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert.

When the Ländler moved from the farmyard to the ballroom, and when the dancing couples started to come from the bourgeois and aristocratic classes, the Ländler quickly gave way to its more elegant, swift and exciting cousin, the waltz.

By the first decades of the nineteenth century, the waltz had become the fad of the day. The etymology of its name comes from the German verb waltzen, meaning “to roll”; of course, this refers to the whirling movements performed by the dancing couples. The waltz was as disapproved by the moralists (and also by someone which can hardly be regarded as a moralist, i.e. Lord Byron) as it was loved by the young. In fact, within a social context in which physical intimacy was rigidly restricted, and the opportunities to spend time in close proximity with members of the opposite sex were rare, the waltz provided a welcome possibility for dancing in a tight embrace and for looking one’s partner in the eyes. This was not only an expression of tenderness, but also a need: as everyone who has danced a waltz knows well, unless the dancers fix their gaze into their partner’s eyes, the spinning movement becomes hard to sustain and may give headache or dizziness. For this reason, and also for the exhaustion it caused with its speed, waltzing was discouraged also by some physicians – while, actually, it was highly beneficial as an entertaining form of gymnastics.

Of course Frédéric Chopin had known the waltz already during his first youthful years in Poland, where waltzes were known by the name of “walcerki”. However, he had been accustomed to regard the waltz as a non-artistic form of music; as consumer music, in modern terms. It was simply the background of a social activity, and its music was little more than a series of aural “signs” for the dancers: the triple time marked the steps, and the purposefully and clearly foreseeable harmonic turns indicated the changing figurations of the dance.

It was therefore with some surprise that Chopin encountered a different approach during his stays in Vienna in his early 20s. As he wrote to his former teacher in Warsaw, Józef Franciszek Eisner (1769-1854), “Waltzes are regarded as works here!”. Chopin’s somewhat obscure expression manifests the young musician’s amazement at the fact that a genre he regarded as merely functional could be considered as a work of art. Doubtlessly, the elevation of the waltz to “music” (and to a kind of music which did not necessarily need the physical gestures of dancing in order to be tolerated…) was also due to the beautiful miniature waltzes written by Franz Schubert (published in 1821 and 1830), along with the increasing popularity of the waltzes by Lanner or Johann Strauss senior. Moreover, in 1819 Carl Maria von Weber’s Invitation to the Dance was published, and it proposed an alternative view on the waltz: here, a series of short waltzes was presented as a suite, interspersed with virtuoso and brilliant moments, but also offering an expressive place for lyricism, tenderness and poetry.

It was this concept of waltz which ultimately appealed to Chopin, and led him to compose approximately twenty waltzes during his lifetime. The uncertainty as to the precise number is due to the fact that there are a few known works whose authorship is disputed; another (KK IVb No. 10, “Sostenuto”) is certainly by Chopin, but which bears no title, and therefore may be classified under other rubrics (such as Mazurka or Nocturne); and others whose manuscripts are unavailable (but known to have survived). While Chopin was generally rather selective in the choice of which of his works to publish, the case of his waltzes is unique even by his standards. Only eight of his waltzes were published during his lifetime; others were printed posthumously (but with an opus number) thanks to the efforts of Julian Fontana and of Chopin’s sister; still others were published at a later date and without opus number. Moreover, even in the case of the pieces printed during Chopin’s lifetime, their opus numbers do not correspond to their composition date, and are therefore rather misleading. The two waltzes of op. 69, for example, date respectively from 1835 and 1829; the three pieces of op. 70 cover a time span of no less than thirteen years, having been composed respectively in 1832, 1842 and 1829.

Paradoxically, sometimes it is easier to establish an authoritative version for the unpublished waltzes than for those published during Chopin’s lifetime. In fact, the published waltzes were obviously representative of his most popular works. Therefore, not only there was the printed version, but also a number of manuscript copies, frequently holographs of the composer, which he used to present as gifts or homages to his pupils, friends, acquaintances or lovers. Each of these autographs mirrors a different version of the piece; sometimes, the variants are minimal, but in other cases they involve substantial aspects of the piece’s shape. This should not be seen as a flaw: rather, it reveals a flexible concept of work (almost an “open work”, as we would say in today’s terms), which could also be tailored to the receiver’s taste or ability.

In general, Chopin’s waltzes were not conceived as pieces to accompany dancing proper, although most of them have later been employed as ballet music or as accompaniments to other dance-like activities (such as ice skating or rhythmic gymnastics). Therefore, they can display a much richer harmonic structure, more flexible rhythmic patterns (in which, paradoxically, frequently the underlying triple time conflicts with tunes with a binary subdivision), and a virtuoso component which attracts the listener’s attention on the pianist’s brilliancy and mastery of the keyboard. The lyrical element is also frequently found, as, for example, in one of the best known pieces in Chopin’s oeuvre, i.e. the beautiful Waltz op. 64 no. 2. The lighthearted aspect of some of them (such as, for example, the so-called “Minute-Waltz”) contrasts with the melancholy found in some others; still others have virtuosity as their keystone, such as in the case of the Grande Valse Brillante op. 18 and of the other works to which the adjective “brillante” has been added.

Chopin continued composing Waltzes until the very last years of his life, and the works he composed in his final years display an extraordinary harmonic complexity, typical of his late style. With him, the waltz acquired the status of masterpiece, and it became able to convey a large variety of emotional states. This is ironic, if one considers how he had doubted the fact that waltzes could be “works”: indeed, he managed to conquer for them pride of place in the piano repertoire of all times.

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads