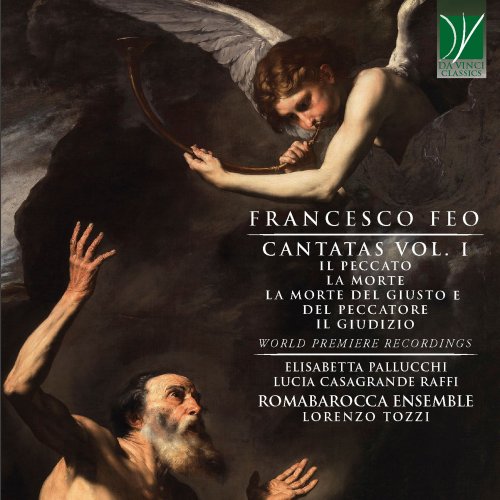

Lorenzo Tozzi, Romabarocca Ensemble - Francesco Feo: Cantatas Vol. 1 - Il peccato, La morte, La morte del giusto e del peccatore, Il giudizio (World Premiere Recordings) (2021)

BAND/ARTIST: Lorenzo Tozzi, Romabarocca Ensemble

- Title: Francesco Feo: Cantatas Vol. 1 - Il peccato, La morte, La morte del giusto e del peccatore, Il giudizio (World Premiere Recordings)

- Year Of Release: 2021

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

- Total Time: 01:10:07

- Total Size: 337 mb

- WebSite: Album Preview

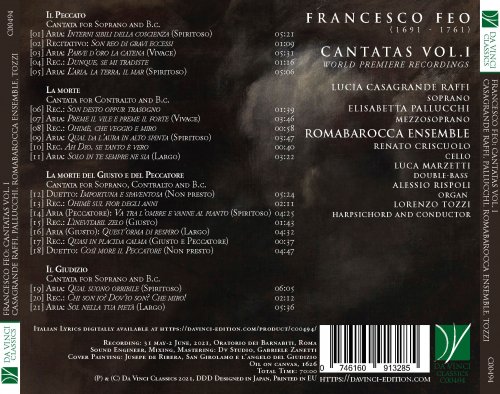

Tracklist

01. Il Peccato: Aria: Interni sibili della coscienza (Spiritoso) [Cantata For Soprano and B.c.]

02. Il Peccato: Recitativo: Son reo di gravi eccessi (Cantata For Soprano and B.c.)

03. Il Peccato: Aria: Parve d’oro la catena (Vivace) [Cantata For Soprano and B.c.]

04. Il Peccato: Rec.: Dunque, se mi tradiste (Cantata For Soprano and B.c.)

05. Il Peccato: Aria: L’aria, la terra, il mar (Spiritoso) [Cantata For Soprano and B.c.]

06. La morte: Rec.: Son desto oppur trasogno (Cantata For Contralto and B.c.)

07. La morte: Aria: Preme il vile e preme il forte (Vivace) [Cantata For Contralto and B.c.]

08. La morte: Rec.: Ohimè, che veggio e miro (Cantata For Contralto and B.c.)

09. La morte: Aria: Qual da l’aura in alto spinta (Spiritoso) [Cantata For Contralto and B.c.]

10. La morte: Rec. Ah Dio, se tanto è vero (Cantata For Contralto and B.c.)

11. La morte: Aria: Solo in te sempre ne sia (Largo) [Cantata For Contralto and B.c.]

12. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Duetto: Importuna e spaventosa (Non presto) [Cantata For Soprano, Contralto and B.c.]

13. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Rec.: Ohimè sul fior degli anni (Cantata For Soprano, Contralto and B.c.)

14. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Aria (Peccatore): Va tra l’ombre e vanne al pianto (Spiritoso)

15. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Rec.: L’inevitabil zelo (Giusto) [Cantata For Soprano, Contralto and B.c.]

16. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Aria (Giusto): Quest’orma di respiro (Largo)

17. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Rec.: Quasi in placida calma (Giusto e Peccatore) [Cantata For Soprano, Contralto and B.c.]

18. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Duetto: Così more il Peccatore (Non presto) [Cantata For Soprano, Contralto and B.c.]

19. Il Giudizio: Aria: Qual suono orribile (Spiritoso) [Cantata For Soprano and B.c.]

20. Il Giudizio: Rec.: Chi son io? Dov’io son? Che miro! (Cantata For Soprano and B.c.)

21. Il Giudizio: Aria: Sol nella tua pietà (Largo) [Cantata For Soprano and B.c.]

The word Novissima (Latin, neutral plural: the ultimate or last things) refers to the last events that human beings must face at the end of their earthly life. Following the Christian eschatological teaching, the Novissima are mainly four: Death, the last act which concludes earthly life; Judgement, both individual (at the life’s end) and universal (at the end of the world), portrayed in countless frescoes since the Middle Ages; Hell for the wicked, to whom all possibility of redemption is denied; Heaven for those who die in the Grace of God.

Through these elements, Christian doctrine through the centuries aimed at answering the great questions on the future of human beings after their life, and on the destiny of their souls and bodies. In fact, humans always tried and affirmed the presence of a life – be it merely spiritual – after death, in the illusion of an immortality which could exorcize fear, loneliness and despair. Starting with the Middle Ages, the post-mortem future was conditioned by one’s lived life; from this eternal bliss or damnation may derive. They are made definitive after the last judgment, in which all will be called for eternity to fire or to the reward of beatitude.

These themes were for centuries among the main lines of Catholic teaching and are splendidly documented by music with a religious inspiration. Among the many works, one could cite, for example, the moral of Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s Rappresentazione di Anima e di Corpo (Rome, 1600), of La Vita Humana by Marco Marazzoli (Rome, 1658), the Oratorio Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno by Händel (Rome, 1708), or Giovanni Legrenzi’s La morte del cuor penitente (Venice, 1673). In all of them, the subject matter is always the struggle between good and evil, whose result will determine the human being’s otherworldly future. This teaching is not without admonitions and considerations. From Alessandro Melani’s L’empio punito (Rome, 1669) these will grow to encompass Mozart’s Don Giovanni (“Pentiti, scellerato!”), on the same Counter-reformation and Jesuitic line. Indeed, the subject of the fleetingness of life and of the earthly things is constantly repeated in the Bible (Pulvis es et pulvis reverteris, Genesis 3:19, or Vanitas vanitatum in Qohelet 1:2), but also in the works by almost all of the Church Fathers, starting with Origen and Tertullian (De anima), including Cyprian and Augustine (The City of God) and up to the medieval Sponsus, a liturgical drama in which the unwise virgins await their final fate. Eschatological terms are found in the later texts, reaching the eighteenth century thanks to the indications of the Tridentine Council, as gathered in Robert Bellarmine’s reflections (De arte bene moriendi, Rome 1620) and in those by the Church Doctor Alfonso Maria de’ Liguori (Massime eterne, Naples 1728) who, in his daily spiritual meditations, discusses at length the ultimate realities.

De’ Liguori, a Neapolitan, who had been ordained to priesthood in 1726 and who taught moral theology, was a balanced figure who offered a tempered view between the rigid pessimism of the anti-Papal Jansenism and the Jesuits, considered to be more permissive. He must have played a certain influence on the anonymous compiler of the lyrics of Francesco Feo’s sacred cantatas, performed in Naples and recorded here for the first time.

This, then, is the underlying subject for the 29 Sacred Cantatas and the 9 Dialogues by Feo, found in a manuscript collection at London’s British Library, and dated between 1725 and 1739. It is a series of Cantatas (19 for solo voice and continuo, 2 for bass, 7 for two voices and just one for three), possibly written for the Church of the Annunziata in Naples, where Feo was chapel master from 1726. Among them, some were selected as they splendidly define an ideal spiritual itinerary. This itinerary is traced by the anonymous author (almost certainly a churchman) who wrote the lyrics, with powerfully evocative imagery gladdened by a splendid music, which aimed at conveying the eschatological message in a fashion fully palatable to the listeners.

In spite of his centrality within the glorious Neapolitan school of the eighteenth century, Francesco Feo (1691-1761) is among the most unjustly forgotten of his colleagues. He had studied since 1704 at the Conservatorio della Pietà dei Turchini with Andrea Basso and later with Nicola Fago; among his fellow students were Leonardo Leo and Giuseppe De Majo. At the early age of 22 he debuted as an operatic composer with L’amor tiranno at the Teatro San Bartolomeo, followed by the oratorio Il martirio di S. Caterina (1714) and in 1720 by the opera seria Teuzzone. Still, the success which definitively established his name was that of Siface (Teatro San Bartolomeo, May 1723), in which he promoted the debut as a librettist of no less a poet than a young Metastasio (among the performers were the castrato Nicolini and the female singer Bulgarelli).

His teaching activity was also important: for sixteen years starting in 1723 he was primo maestro at the Conservatorio di Sant’Onofrio, where he taught Jommelli, Latilla, and his nephew Gennaro Manna. From 1739 he was active for four years at the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo, where Abos was his assistant and Insanguine one of his students. He retired from teaching after twenty years and consecrated himself to composition, prevailingly consisting of sacred works for the Church of the Annunziata (where he was chapel master from 1726 to 1745) or for the Church of Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco (in Naples’ Via dei Tribunali), where he was chapel master from 1731 to 1750. It is therefore very likely that his spiritual cantatas were composed within the timeframe 1723-1743.

His operatic output (about a dozen titles) is still notable for its quality and is currently being studied by music historians; however, his flagship consists of his sacred works, including 14 oratorios, lectiones, Psalms, dialogues, Lamentations, three Passions, Litanies, 18 Masses, 27 Motets, and Vespers.

He was appreciated not only by the English historiographer and traveler Charles Burney, who likened Feo to Vinci, Pergolesi, Leo and even to Handel (for the invention and musical setting of the lyrics), but also by the German composer and music critic Johann Friedrich Reichardt, who in 1719 likened him to Bach and Handel for his sacred output. Furthermore, Hasse called him “a worthy virtuoso, full of practice and care in leading the musical matter”.

Coeval chronicles mention him always with flattering titles, such as “virtuosissimo”, “famous chapel master”, “skilled youth” and “universally applauded virtuoso”. Among his friends were Leonardo Vinci and Pergolesi. Feo was close to Pergolesi in the last weeks of the latter’s life in Pozzuoli, and inherited from him the manuscript of the extremely famous Stabat Mater. Feo also earned the esteem of the celebrated Padre Martini in Bologna: at the Civico Museo Bibliografico of Bologna are currently found a portrait of the composer as a young man and five letters from 1749, whilst another portrait is found at the Conservatory of San Pietro a Majella in Naples.

The Cantatas selected here constitute almost the first stage of an ideal spiritual itinerary: From Peccato (Sin: G major, F major, G major) to Morte (Death: E major, F major, D major) to the dialogue among two characters La morte del giusto e del peccatore (The Righteous and the Sinful Man’s Death: B-flat major, E-flat major, F minor, G minor), then Giudizio, the individual judgment (F major/minor) to be followed by the Giudizio Universale (in two parts), by the Inferno, by L’eternità, and by the concluding moral dialogue between Tirsi and Elpino called Il fine dell’uomo. These cantatas normally consist of two or three arias, always in the da capo form, following Scarlatti’s model, and interspersed by brief and dramatic secco recitatives. The continuo’s scoring is striking for its very mobile traits; it is almost in counterpoint to the voice, and is always powerfully characterized on the rhythmical plane.

Every aria has a precise musical identity of its own and a characterizing beginning. The subjects are the usual ones found in a certain apocalyptic literature, underlining the deceit of transient realities; however, the musical scoring is skilled, expert, and will capture and captivate the listener. So pleasurable is the listening experience that it will dilute the crude “representation” and the dramatic style of the apocalyptic subject.

In the originality of his musical inventions, one realizes Feo’s mastery of both the Church- or antiquus style (counterpoint) and of the modern idiom of accompanied monody following the authentically Neapolitan fashion of the time. In fact, Feo tends almost to depict some short scenes, and remains always very theatrical in his aural descriptions. One can find some nearly perfect Fugue subjects at the beginning of the Aria “Parve d’oro la catena” (the second of Il Peccato) and “Così more il peccatore” (the concluding duet of La morte del giusto e del peccatore). Some variety is found in the ordering of Recitatives and Arias: Il Peccato (ArArA), La Morte (rArArA), La morte del giusto e del peccatore, with a perfectly symmetrical structure (Duet rArAr Duet) and the brief Giudizio (ArA)

As has been stated, some variety is also found in the choice of the main keys of the Arias and Duets. In spite of dark and implicitly intimidating lyrics, Feo employs almost always the major mode with few exceptions (e.g. at the closing of the clarifying Duet between the Righteous and the Sinful Man, and in the Giudizio). He also employs a rather broad range of keys, from four sharps (“Preme il vile e preme il forte” in E major) to four flats (“Quest’orma di respire” and “Sol nella tua pietà”, both in F minor). In the central section (in B major) of the aria “Preme il vile” we reach even the key of G-sharp minor, the minor relative of the dominant of the piece’s main key (E major).

In a time when epidemics, wars and famine were constant, it was not difficult to live in a constant state of fear. “Skulls and Death’s sickles were everywhere”, in historian De Rosa’s words, “in the churches, below the pulpits, under the arches, in the paintings, in the monumental buildings, both secular and religious. One lived in the company of Death”. This appears to have been the soil on which spiritual cantatas such as those recorded here were created, on the wake of the Post-Tridentine heritage between rigour and indulgence.

01. Il Peccato: Aria: Interni sibili della coscienza (Spiritoso) [Cantata For Soprano and B.c.]

02. Il Peccato: Recitativo: Son reo di gravi eccessi (Cantata For Soprano and B.c.)

03. Il Peccato: Aria: Parve d’oro la catena (Vivace) [Cantata For Soprano and B.c.]

04. Il Peccato: Rec.: Dunque, se mi tradiste (Cantata For Soprano and B.c.)

05. Il Peccato: Aria: L’aria, la terra, il mar (Spiritoso) [Cantata For Soprano and B.c.]

06. La morte: Rec.: Son desto oppur trasogno (Cantata For Contralto and B.c.)

07. La morte: Aria: Preme il vile e preme il forte (Vivace) [Cantata For Contralto and B.c.]

08. La morte: Rec.: Ohimè, che veggio e miro (Cantata For Contralto and B.c.)

09. La morte: Aria: Qual da l’aura in alto spinta (Spiritoso) [Cantata For Contralto and B.c.]

10. La morte: Rec. Ah Dio, se tanto è vero (Cantata For Contralto and B.c.)

11. La morte: Aria: Solo in te sempre ne sia (Largo) [Cantata For Contralto and B.c.]

12. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Duetto: Importuna e spaventosa (Non presto) [Cantata For Soprano, Contralto and B.c.]

13. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Rec.: Ohimè sul fior degli anni (Cantata For Soprano, Contralto and B.c.)

14. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Aria (Peccatore): Va tra l’ombre e vanne al pianto (Spiritoso)

15. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Rec.: L’inevitabil zelo (Giusto) [Cantata For Soprano, Contralto and B.c.]

16. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Aria (Giusto): Quest’orma di respiro (Largo)

17. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Rec.: Quasi in placida calma (Giusto e Peccatore) [Cantata For Soprano, Contralto and B.c.]

18. La morte del Giusto e del Peccatore: Duetto: Così more il Peccatore (Non presto) [Cantata For Soprano, Contralto and B.c.]

19. Il Giudizio: Aria: Qual suono orribile (Spiritoso) [Cantata For Soprano and B.c.]

20. Il Giudizio: Rec.: Chi son io? Dov’io son? Che miro! (Cantata For Soprano and B.c.)

21. Il Giudizio: Aria: Sol nella tua pietà (Largo) [Cantata For Soprano and B.c.]

The word Novissima (Latin, neutral plural: the ultimate or last things) refers to the last events that human beings must face at the end of their earthly life. Following the Christian eschatological teaching, the Novissima are mainly four: Death, the last act which concludes earthly life; Judgement, both individual (at the life’s end) and universal (at the end of the world), portrayed in countless frescoes since the Middle Ages; Hell for the wicked, to whom all possibility of redemption is denied; Heaven for those who die in the Grace of God.

Through these elements, Christian doctrine through the centuries aimed at answering the great questions on the future of human beings after their life, and on the destiny of their souls and bodies. In fact, humans always tried and affirmed the presence of a life – be it merely spiritual – after death, in the illusion of an immortality which could exorcize fear, loneliness and despair. Starting with the Middle Ages, the post-mortem future was conditioned by one’s lived life; from this eternal bliss or damnation may derive. They are made definitive after the last judgment, in which all will be called for eternity to fire or to the reward of beatitude.

These themes were for centuries among the main lines of Catholic teaching and are splendidly documented by music with a religious inspiration. Among the many works, one could cite, for example, the moral of Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s Rappresentazione di Anima e di Corpo (Rome, 1600), of La Vita Humana by Marco Marazzoli (Rome, 1658), the Oratorio Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno by Händel (Rome, 1708), or Giovanni Legrenzi’s La morte del cuor penitente (Venice, 1673). In all of them, the subject matter is always the struggle between good and evil, whose result will determine the human being’s otherworldly future. This teaching is not without admonitions and considerations. From Alessandro Melani’s L’empio punito (Rome, 1669) these will grow to encompass Mozart’s Don Giovanni (“Pentiti, scellerato!”), on the same Counter-reformation and Jesuitic line. Indeed, the subject of the fleetingness of life and of the earthly things is constantly repeated in the Bible (Pulvis es et pulvis reverteris, Genesis 3:19, or Vanitas vanitatum in Qohelet 1:2), but also in the works by almost all of the Church Fathers, starting with Origen and Tertullian (De anima), including Cyprian and Augustine (The City of God) and up to the medieval Sponsus, a liturgical drama in which the unwise virgins await their final fate. Eschatological terms are found in the later texts, reaching the eighteenth century thanks to the indications of the Tridentine Council, as gathered in Robert Bellarmine’s reflections (De arte bene moriendi, Rome 1620) and in those by the Church Doctor Alfonso Maria de’ Liguori (Massime eterne, Naples 1728) who, in his daily spiritual meditations, discusses at length the ultimate realities.

De’ Liguori, a Neapolitan, who had been ordained to priesthood in 1726 and who taught moral theology, was a balanced figure who offered a tempered view between the rigid pessimism of the anti-Papal Jansenism and the Jesuits, considered to be more permissive. He must have played a certain influence on the anonymous compiler of the lyrics of Francesco Feo’s sacred cantatas, performed in Naples and recorded here for the first time.

This, then, is the underlying subject for the 29 Sacred Cantatas and the 9 Dialogues by Feo, found in a manuscript collection at London’s British Library, and dated between 1725 and 1739. It is a series of Cantatas (19 for solo voice and continuo, 2 for bass, 7 for two voices and just one for three), possibly written for the Church of the Annunziata in Naples, where Feo was chapel master from 1726. Among them, some were selected as they splendidly define an ideal spiritual itinerary. This itinerary is traced by the anonymous author (almost certainly a churchman) who wrote the lyrics, with powerfully evocative imagery gladdened by a splendid music, which aimed at conveying the eschatological message in a fashion fully palatable to the listeners.

In spite of his centrality within the glorious Neapolitan school of the eighteenth century, Francesco Feo (1691-1761) is among the most unjustly forgotten of his colleagues. He had studied since 1704 at the Conservatorio della Pietà dei Turchini with Andrea Basso and later with Nicola Fago; among his fellow students were Leonardo Leo and Giuseppe De Majo. At the early age of 22 he debuted as an operatic composer with L’amor tiranno at the Teatro San Bartolomeo, followed by the oratorio Il martirio di S. Caterina (1714) and in 1720 by the opera seria Teuzzone. Still, the success which definitively established his name was that of Siface (Teatro San Bartolomeo, May 1723), in which he promoted the debut as a librettist of no less a poet than a young Metastasio (among the performers were the castrato Nicolini and the female singer Bulgarelli).

His teaching activity was also important: for sixteen years starting in 1723 he was primo maestro at the Conservatorio di Sant’Onofrio, where he taught Jommelli, Latilla, and his nephew Gennaro Manna. From 1739 he was active for four years at the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo, where Abos was his assistant and Insanguine one of his students. He retired from teaching after twenty years and consecrated himself to composition, prevailingly consisting of sacred works for the Church of the Annunziata (where he was chapel master from 1726 to 1745) or for the Church of Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco (in Naples’ Via dei Tribunali), where he was chapel master from 1731 to 1750. It is therefore very likely that his spiritual cantatas were composed within the timeframe 1723-1743.

His operatic output (about a dozen titles) is still notable for its quality and is currently being studied by music historians; however, his flagship consists of his sacred works, including 14 oratorios, lectiones, Psalms, dialogues, Lamentations, three Passions, Litanies, 18 Masses, 27 Motets, and Vespers.

He was appreciated not only by the English historiographer and traveler Charles Burney, who likened Feo to Vinci, Pergolesi, Leo and even to Handel (for the invention and musical setting of the lyrics), but also by the German composer and music critic Johann Friedrich Reichardt, who in 1719 likened him to Bach and Handel for his sacred output. Furthermore, Hasse called him “a worthy virtuoso, full of practice and care in leading the musical matter”.

Coeval chronicles mention him always with flattering titles, such as “virtuosissimo”, “famous chapel master”, “skilled youth” and “universally applauded virtuoso”. Among his friends were Leonardo Vinci and Pergolesi. Feo was close to Pergolesi in the last weeks of the latter’s life in Pozzuoli, and inherited from him the manuscript of the extremely famous Stabat Mater. Feo also earned the esteem of the celebrated Padre Martini in Bologna: at the Civico Museo Bibliografico of Bologna are currently found a portrait of the composer as a young man and five letters from 1749, whilst another portrait is found at the Conservatory of San Pietro a Majella in Naples.

The Cantatas selected here constitute almost the first stage of an ideal spiritual itinerary: From Peccato (Sin: G major, F major, G major) to Morte (Death: E major, F major, D major) to the dialogue among two characters La morte del giusto e del peccatore (The Righteous and the Sinful Man’s Death: B-flat major, E-flat major, F minor, G minor), then Giudizio, the individual judgment (F major/minor) to be followed by the Giudizio Universale (in two parts), by the Inferno, by L’eternità, and by the concluding moral dialogue between Tirsi and Elpino called Il fine dell’uomo. These cantatas normally consist of two or three arias, always in the da capo form, following Scarlatti’s model, and interspersed by brief and dramatic secco recitatives. The continuo’s scoring is striking for its very mobile traits; it is almost in counterpoint to the voice, and is always powerfully characterized on the rhythmical plane.

Every aria has a precise musical identity of its own and a characterizing beginning. The subjects are the usual ones found in a certain apocalyptic literature, underlining the deceit of transient realities; however, the musical scoring is skilled, expert, and will capture and captivate the listener. So pleasurable is the listening experience that it will dilute the crude “representation” and the dramatic style of the apocalyptic subject.

In the originality of his musical inventions, one realizes Feo’s mastery of both the Church- or antiquus style (counterpoint) and of the modern idiom of accompanied monody following the authentically Neapolitan fashion of the time. In fact, Feo tends almost to depict some short scenes, and remains always very theatrical in his aural descriptions. One can find some nearly perfect Fugue subjects at the beginning of the Aria “Parve d’oro la catena” (the second of Il Peccato) and “Così more il peccatore” (the concluding duet of La morte del giusto e del peccatore). Some variety is found in the ordering of Recitatives and Arias: Il Peccato (ArArA), La Morte (rArArA), La morte del giusto e del peccatore, with a perfectly symmetrical structure (Duet rArAr Duet) and the brief Giudizio (ArA)

As has been stated, some variety is also found in the choice of the main keys of the Arias and Duets. In spite of dark and implicitly intimidating lyrics, Feo employs almost always the major mode with few exceptions (e.g. at the closing of the clarifying Duet between the Righteous and the Sinful Man, and in the Giudizio). He also employs a rather broad range of keys, from four sharps (“Preme il vile e preme il forte” in E major) to four flats (“Quest’orma di respire” and “Sol nella tua pietà”, both in F minor). In the central section (in B major) of the aria “Preme il vile” we reach even the key of G-sharp minor, the minor relative of the dominant of the piece’s main key (E major).

In a time when epidemics, wars and famine were constant, it was not difficult to live in a constant state of fear. “Skulls and Death’s sickles were everywhere”, in historian De Rosa’s words, “in the churches, below the pulpits, under the arches, in the paintings, in the monumental buildings, both secular and religious. One lived in the company of Death”. This appears to have been the soil on which spiritual cantatas such as those recorded here were created, on the wake of the Post-Tridentine heritage between rigour and indulgence.

Year 2021 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads