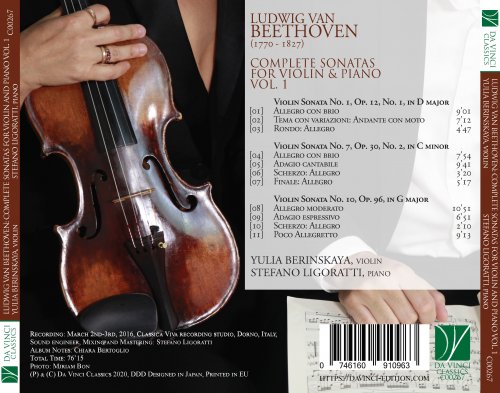

Yulia Berinskaya - Ludwig van Beethoven: Complete Sonatas for Violin & Piano Vol. 1 (2020)

BAND/ARTIST: Yulia Berinskaya

- Title: Ludwig van Beethoven: Complete Sonatas for Violin & Piano Vol. 1

- Year Of Release: 2020

- Label: Da Vinci Classics

- Genre: Classical

- Quality: FLAC (tracks)

- Total Time: 76:10 min

- Total Size: 320 MB

- WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Violin Sonata No. 1 in D Major, Op. 12 No.1: I. Allegro con brio

02. Violin Sonata No. 1 in D Major, Op. 12 No.1: II. Tema con variazioni. Andante con moto

03. Violin Sonata No. 1 in D Major, Op. 12 No.1: III. Rondo. Allegro

04. Violin Sonata No. 7 in C Minor, Op. 30 No. 2: I. Allegro con brio

05. Violin Sonata No. 7 in C Minor, Op. 30 No. 2: II. Adagio cantabile

06. Violin Sonata No. 7 in C Minor, Op. 30 No. 2: III. Scherzo. Allegro - Trio

07. Violin Sonata No. 7 in C Minor, Op. 30 No. 2: IV. Finale. Allegro

08. Violin Sonata No. 10 in G Major, Op. 96: I. Allegro moderato

09. Violin Sonata No. 10 in G Major, Op. 96: II. Adagio espressivo

10. Violin Sonata No. 10 in G Major, Op. 96: III. Scherzo. Allegro

11. Violin Sonata No. 10 in G Major, Op. 96: IV. Poco Allegretto

As happened with many of the greatest composers in the past, also Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) could play a bowed string instrument along with keyboard instruments such as the harpsichord or fortepiano. What the harpsichord and fortepiano lack (in particular, the capability of sustaining and modifying a tone after it has been produced, and to enliven it through vibrato) is instead one of the fortes of the violin; and the limitations of the violin as concerns texture, tessitura, chordal writing and polyphony are abundantly compensated by the keyboard’s potential. A professional musician, and particularly a composer, who can master these two types of instrument, has certainly acquired a deep insight into two of the most important media of sound production, and the capability of understanding the melodic, harmonic and polyphonic structures on which music is built. And when the violin and a keyboard instrument play together, the combination of their tones creates a beautiful sound mixture and a perfect pair; however, this pair is not without its challenges – both for the composer and for the performers. While it is true that the volume of sound produced by earlier keyboard instruments is no match for today’s concert grand pianos (and thus the risk of drowning the violin’s slenderer sound by means of the piano’s thunderous mass of sound was considerably less pronounced in the past), the important differences in tone quality and quantity between the two instruments are not to be overlooked. The constant dialogue required by a work of “true” chamber music is not easily achieved when one of the instruments can vibrate and the other cannot, when one can play pizzicato and the other (at least before John Cage!) cannot, but also when one can blend different harmonies played at different times (as Beethoven liked to experiment through piano pedaling) and the other does not possess anything similar to that effect. Thus, considering the violin’s potential for an expressive sound and for brilliant virtuosity, a possible solution is to consider the violin almost as an instrumental version of an operatic singer, in the style of a primadonna, the undisputed protagonist of the stage, with all of her idiosyncrasies; the piano thus becomes a substitute for the orchestra, by providing an accompaniment which may possess some degree of musical interest, but is normally subordinated to the violin: this was the underlying concept behind many solo violin works composed from the Baroque to the modern era. On the other hand, the opposite choice could also be made (and, in this case, it was typical for a shorter period of time, with most works of this kind being found in the eighteenth century): the piano was the protagonist, and the violin limited itself to adding its voice to the piano’s right hand, thus lending to the piano’s sound those qualities it did not possess.

Beethoven’s Violin Sonatas are rooted within this tradition (mirrored by the fact that he always gave them the title of “Sonata for the fortepiano and a violin”, rather than the other way around), but he was one of the first composers who really considered the two instruments as being on a par, while also respecting and promoting the unique qualities of each. He wrote ten masterpieces for this particular duo, and it can almost be said that those ideals of human brotherhood in which he so deeply believed are embodied in these works. Here, two very different musical individuals establish a musical dialogue which reveals true friendship, a mutual support, a reciprocal alliance; in spite of moments in which the two may struggle with each other for musical supremacy, in most cases their relationship is one of cooperation, respect, trust and confidence.

Different from the Sonatas for solo piano or the string quartets, unfortunately Beethoven did not write Violin Sonatas in his late period; by thinking of the enchanted violin solo in the Benedictus of the Missa Solemnis and of the equally heavenly piano sounds of (to name but one) the Arietta of Piano Sonata op. 111, we may imagine – with a pang of regret – what a Violin Sonata written by Beethoven in the 1820s could have been. However, what we do have is a fascinating corpus of pieces which make up one of the undisputed pillars of the literature for piano and violin of all times, and the most valuable contribution written by one single composer to the repertoire for this particular duo. Thus, this series of CDs published by Da Vinci Classics is a very welcome addition to both its catalogue and to the discography of the Ten Violin Sonatas by Beethoven.

Volume One of this series comprises two Sonatas belonging to opuses comprising more than one sonata, and the standalone of op. 96, the last Violin Sonata composed by Beethoven.

The set of three Sonatas op. 12 was written by Beethoven in his late twenties, and is dedicated to his mentor Antonio Salieri. The reviewers were puzzled by the originality of these pieces, and their lack of conventionality was not perceived as an artistic discovery or development; rather, it puzzled the listeners, so that the overall impression could be summed up in the words of a critic: these Sonatas present “a forced attempt at strange modulations, an aversion to the conventional key relationships, a piling up of difficulty upon difficulty”. The first Sonata (in D major, op. 12 no. 1) efficaciously exemplifies the novelties of Beethoven’s style with respect to that of his contemporaries: it is a cascade of brilliant passages, a display of the quintessentially Beethovenian sforzandos, of abrupt changes of key (such as the sudden juxtaposition of A major and F major between exposition and development in the first movement), including a saucy use of irregular rhythmic groupings and of dynamic contrasts. The predominant mood is the exuberant, joyful and slightly boisterous attitude of the young Beethoven, with his defiance of the stereotyped solutions and his deliberate (and extremely refined) rudeness. By way of contrast, the second movement is an elegant Theme with Variations, which constitutes one of the relatively early examples in a genre which Beethoven would practise until his very last opus numbers. Here there is room for a variety of styles, including a display of utter virtuosity and the extreme contrasts of Variation III, in the minor mode. The tensions are reconciled in the last Variation, characterized by wavering syncopations and sighing gestures. The third movement, a Rondo, has a cheerful and rather rustic principal theme, which alternates with very brilliant secondary sections with a thick and quick texture in both instruments; the Sonata closes in a very humorous fashion.

Just a few years later (the first Sonata was written in 1798, while the seventh in 1802), the situation had changed dramatically: the C minor Sonata belongs in another set of three works (op. 30), composed at roughly the same time as the Testament of Heiligenstadt, the justly and sadly famous letter written by Beethoven to his brothers; he was quickly sliding into deafness, and had been seized by suicidal thoughts, from which music only had managed to free him. Of the three, it is precisely no. 2 (recorded here) the one which displays more clearly the composer’s mood. The key of C minor is that of the tragic hero, in Beethoven’s music; the dark, broken opening gestures of this Sonata mirror the somber atmosphere surrounding the composer. There are timpani-like tremolos in the pianist’s left-hand part; streams of scales and arpeggios in both instruments, but also a tremendous will to live, expressed with an almost desperate vitality. The central Adagio cantabile is one of the most beautiful slow movements in the entire set of the Ten Sonatas, with a prayerful mood and an intense, impassioned lyricism, ending in an almost transcendent fashion with pearly strings of murmured scales. The following Scherzo, in C major, seems to find once more Beethoven’s humorous vein, particularly in the funny and joking game of “catch-me-if-you-can” enacted by the two instruments, and in the Papageno-like repeated notes played by the violin. The closing Finale wonderfully manages to combine gloomy and almost buffoonish moments, without weakening either. The concluding Coda further increases the pace (a breath-taking Presto) and rushes towards a brusque and sharp ending.

Ten years later, in 1812, Beethoven was in his early forties, and he had navigated a long way. While his deafness was constantly worsening, he was slowly managing to find an interior plane of serenity, which shines in the smiling opening of Sonata no. 10, op. 96. The gentle, caressing trill of the solo violin throws a warm light on the entire work, where irony and tenderness are both abundantly present. The two instruments seem really to have established a tight friendship and partnership, frequently intertwining their lines in a compositional style which seems to seek a new timbre, resulting from the interaction of the two sounds. The second movement has once more something of the religious song; it is concise but very touching and intensely meditative. A number of Sforzandos punctuate once more the Scherzo, which displays a very orchestral concept, while the principal theme of the Poco Allegretto has an almost childlike and naïve quality. This movement has much in common with the equally poetic and nearly Schubertian Piano Sonata op. 90, and it comprises a surprising and enchanted slow section – almost as a glimpse on another world. The entire cycle of the Ten Sonatas closes however on a positive, cheerful and optimistic note: the broad smile which the music of the young Beethoven had shown and which had been seemingly lost in the tragic following years has now been recovered, possibly also thanks to the musical “brotherhood” symbolized by the friendly alliance of the violin with the piano.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

Beethoven’s Violin Sonatas are rooted within this tradition (mirrored by the fact that he always gave them the title of “Sonata for the fortepiano and a violin”, rather than the other way around), but he was one of the first composers who really considered the two instruments as being on a par, while also respecting and promoting the unique qualities of each. He wrote ten masterpieces for this particular duo, and it can almost be said that those ideals of human brotherhood in which he so deeply believed are embodied in these works. Here, two very different musical individuals establish a musical dialogue which reveals true friendship, a mutual support, a reciprocal alliance; in spite of moments in which the two may struggle with each other for musical supremacy, in most cases their relationship is one of cooperation, respect, trust and confidence.

Different from the Sonatas for solo piano or the string quartets, unfortunately Beethoven did not write Violin Sonatas in his late period; by thinking of the enchanted violin solo in the Benedictus of the Missa Solemnis and of the equally heavenly piano sounds of (to name but one) the Arietta of Piano Sonata op. 111, we may imagine – with a pang of regret – what a Violin Sonata written by Beethoven in the 1820s could have been. However, what we do have is a fascinating corpus of pieces which make up one of the undisputed pillars of the literature for piano and violin of all times, and the most valuable contribution written by one single composer to the repertoire for this particular duo. Thus, this series of CDs published by Da Vinci Classics is a very welcome addition to both its catalogue and to the discography of the Ten Violin Sonatas by Beethoven.

Volume One of this series comprises two Sonatas belonging to opuses comprising more than one sonata, and the standalone of op. 96, the last Violin Sonata composed by Beethoven.

The set of three Sonatas op. 12 was written by Beethoven in his late twenties, and is dedicated to his mentor Antonio Salieri. The reviewers were puzzled by the originality of these pieces, and their lack of conventionality was not perceived as an artistic discovery or development; rather, it puzzled the listeners, so that the overall impression could be summed up in the words of a critic: these Sonatas present “a forced attempt at strange modulations, an aversion to the conventional key relationships, a piling up of difficulty upon difficulty”. The first Sonata (in D major, op. 12 no. 1) efficaciously exemplifies the novelties of Beethoven’s style with respect to that of his contemporaries: it is a cascade of brilliant passages, a display of the quintessentially Beethovenian sforzandos, of abrupt changes of key (such as the sudden juxtaposition of A major and F major between exposition and development in the first movement), including a saucy use of irregular rhythmic groupings and of dynamic contrasts. The predominant mood is the exuberant, joyful and slightly boisterous attitude of the young Beethoven, with his defiance of the stereotyped solutions and his deliberate (and extremely refined) rudeness. By way of contrast, the second movement is an elegant Theme with Variations, which constitutes one of the relatively early examples in a genre which Beethoven would practise until his very last opus numbers. Here there is room for a variety of styles, including a display of utter virtuosity and the extreme contrasts of Variation III, in the minor mode. The tensions are reconciled in the last Variation, characterized by wavering syncopations and sighing gestures. The third movement, a Rondo, has a cheerful and rather rustic principal theme, which alternates with very brilliant secondary sections with a thick and quick texture in both instruments; the Sonata closes in a very humorous fashion.

Just a few years later (the first Sonata was written in 1798, while the seventh in 1802), the situation had changed dramatically: the C minor Sonata belongs in another set of three works (op. 30), composed at roughly the same time as the Testament of Heiligenstadt, the justly and sadly famous letter written by Beethoven to his brothers; he was quickly sliding into deafness, and had been seized by suicidal thoughts, from which music only had managed to free him. Of the three, it is precisely no. 2 (recorded here) the one which displays more clearly the composer’s mood. The key of C minor is that of the tragic hero, in Beethoven’s music; the dark, broken opening gestures of this Sonata mirror the somber atmosphere surrounding the composer. There are timpani-like tremolos in the pianist’s left-hand part; streams of scales and arpeggios in both instruments, but also a tremendous will to live, expressed with an almost desperate vitality. The central Adagio cantabile is one of the most beautiful slow movements in the entire set of the Ten Sonatas, with a prayerful mood and an intense, impassioned lyricism, ending in an almost transcendent fashion with pearly strings of murmured scales. The following Scherzo, in C major, seems to find once more Beethoven’s humorous vein, particularly in the funny and joking game of “catch-me-if-you-can” enacted by the two instruments, and in the Papageno-like repeated notes played by the violin. The closing Finale wonderfully manages to combine gloomy and almost buffoonish moments, without weakening either. The concluding Coda further increases the pace (a breath-taking Presto) and rushes towards a brusque and sharp ending.

Ten years later, in 1812, Beethoven was in his early forties, and he had navigated a long way. While his deafness was constantly worsening, he was slowly managing to find an interior plane of serenity, which shines in the smiling opening of Sonata no. 10, op. 96. The gentle, caressing trill of the solo violin throws a warm light on the entire work, where irony and tenderness are both abundantly present. The two instruments seem really to have established a tight friendship and partnership, frequently intertwining their lines in a compositional style which seems to seek a new timbre, resulting from the interaction of the two sounds. The second movement has once more something of the religious song; it is concise but very touching and intensely meditative. A number of Sforzandos punctuate once more the Scherzo, which displays a very orchestral concept, while the principal theme of the Poco Allegretto has an almost childlike and naïve quality. This movement has much in common with the equally poetic and nearly Schubertian Piano Sonata op. 90, and it comprises a surprising and enchanted slow section – almost as a glimpse on another world. The entire cycle of the Ten Sonatas closes however on a positive, cheerful and optimistic note: the broad smile which the music of the young Beethoven had shown and which had been seemingly lost in the tragic following years has now been recovered, possibly also thanks to the musical “brotherhood” symbolized by the friendly alliance of the violin with the piano.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

Year 2020 | Classical | FLAC / APE

As a ISRA.CLOUD's PREMIUM member you will have the following benefits:

- Unlimited high speed downloads

- Download directly without waiting time

- Unlimited parallel downloads

- Support for download accelerators

- No advertising

- Resume broken downloads